Will south east asia start a domino theory – Will Southeast Asia start a domino theory? This question, echoing Cold War anxieties, feels increasingly relevant in today’s complex geopolitical landscape. The region, a vibrant tapestry of diverse cultures, economies, and political systems, faces a confluence of challenges: rising great power competition, internal conflicts, economic disparities, and the looming threat of climate change. Understanding the historical context of domino theory’s application in Southeast Asia, alongside an analysis of current power dynamics, internal political stability, and external influences, is crucial to assessing the likelihood of a cascading crisis.

This exploration delves into the intricacies of regional security, economic factors, social dynamics, and military capabilities to paint a nuanced picture of Southeast Asia’s future.

From the historical impacts of the Cold War to the present-day influence of China and the United States, the forces shaping Southeast Asia are multifaceted and interconnected. This examination will consider the stability of individual nations, analyzing their democratic governance, internal conflicts, and political systems. Further, we will explore the region’s economic interdependence, the role of social and cultural factors, and the impact of military capabilities and regional security organizations.

By weaving together these threads, we aim to provide a comprehensive assessment of the potential for a domino effect in Southeast Asia, offering insights into the region’s trajectory and its implications for global stability.

Historical Context of Domino Theory in Southeast Asia

The Domino Theory, that the fall of one Southeast Asian nation to communism would trigger the collapse of its neighbors, wasn’t just a Cold War buzzword; it was a deeply influential framework shaping US foreign policy in the region. Its application in Southeast Asia, however, was far from straightforward, interwoven with complex local dynamics and often proving a poor predictor of real-world events.

Understanding its historical context requires examining specific events and geopolitical factors.The historical application of the Domino Theory in Southeast Asia is marked by a series of interconnected events, each interpreted through the prism of communist expansion. The theory’s proponents pointed to a chain reaction, beginning with the communist victory in Vietnam. This interpretation, however, often overlooked the nuanced internal struggles and external influences shaping each nation’s political trajectory.

The Fall of Indochina and its Regional Implications

The French defeat in Vietnam in 1954, culminating in the Geneva Accords, served as a pivotal moment. The division of Vietnam into North and South, coupled with the subsequent escalation of the Vietnam War, fueled fears of a communist domino effect spreading throughout the region. The US intervention in Vietnam, justified largely by the Domino Theory, significantly impacted neighboring Laos and Cambodia, drawing them into the conflict and destabilizing their respective governments.

The resulting conflicts, characterized by proxy wars and intense political maneuvering, led to the rise of communist movements in these countries, seemingly validating, at least for a time, the Domino Theory’s predictions. However, the internal political and social factors at play often overshadowed the simple “domino” narrative. For example, the Khmer Rouge’s rise to power in Cambodia was far more complex than simply a consequence of the Vietnam War, rooted in deeply seated internal issues and the devastating impact of the war on the Cambodian countryside.

Comparison with Domino Theory Applications in Other Regions

While the Domino Theory was most prominently applied in Southeast Asia, its use in other regions, such as Latin America during the Cold War, reveals important contrasts. In Latin America, the focus was often on preventing the spread of leftist revolutionary movements, rather than specifically communist parties. The interventions, while also influenced by the Domino Theory, frequently involved supporting authoritarian regimes to counter perceived communist threats.

This differs from Southeast Asia, where the US primarily engaged in direct military intervention and support for specific anti-communist governments. The success rate of the theory’s application was arguably lower in Latin America, with many countries experiencing significant social and political upheaval despite US interventions.

Geopolitical Factors Contributing to the Domino Theory in Southeast Asia

The emergence of the Domino Theory in Southeast Asia was fueled by several key geopolitical factors. The post-World War II power vacuum, the rise of communism in China, and the burgeoning Cold War rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union created a fertile ground for fear and intervention. The strategic importance of Southeast Asia, situated at the crossroads of major trade routes and bordering communist China, heightened anxieties about communist expansion.

The perceived fragility of newly independent nations in the region, grappling with internal conflicts and political instability, further fueled the belief that a communist takeover in one country could quickly destabilize the entire area. The US, committed to containing communism, saw the Domino Theory as a justification for extensive military and economic involvement in the region, regardless of the actual complexities of the situation on the ground.

Current Geopolitical Landscape of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia’s geopolitical landscape is a complex tapestry woven with threads of historical rivalries, burgeoning economic interdependence, and the ever-present influence of major global powers. Understanding the current power dynamics is crucial to assessing the region’s stability and its potential trajectory. The region’s future hinges not only on the actions of its own nations but also on the shifting alliances and strategic interests of external actors.The region is characterized by a multifaceted power dynamic, far from a simple bipolar structure.

While the United States and China exert significant influence, ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) member states navigate this external pressure with varying degrees of autonomy and strategic partnerships. Economic ties bind the region together, but historical grievances and competing territorial claims continue to simmer beneath the surface, impacting regional stability.

Key Regional Players and Their Influence

Several nations significantly shape Southeast Asia’s geopolitical landscape. Indonesia, the region’s largest economy and most populous nation, plays a crucial mediating role, often advocating for ASEAN unity and consensus. Its sheer size and economic weight provide considerable influence. Vietnam, having undergone significant economic growth, is a rising power with increasing strategic importance, particularly in its relationship with China and its growing naval capabilities.

Singapore, a small but highly influential state, leverages its economic prowess and strategic location to maintain a significant presence in regional affairs. Thailand, a long-standing regional player, navigates its relationship with both the US and China, maintaining a degree of neutrality while safeguarding its own national interests. The Philippines, despite internal political complexities, holds a key position due to its strategic location in the South China Sea.

These nations, along with others like Malaysia, Brunei, and Myanmar, contribute to the overall dynamism and complexity of the regional power balance. The interplay of their ambitions and interests often shapes the trajectory of regional stability.

Economic Interdependence in Southeast Asia

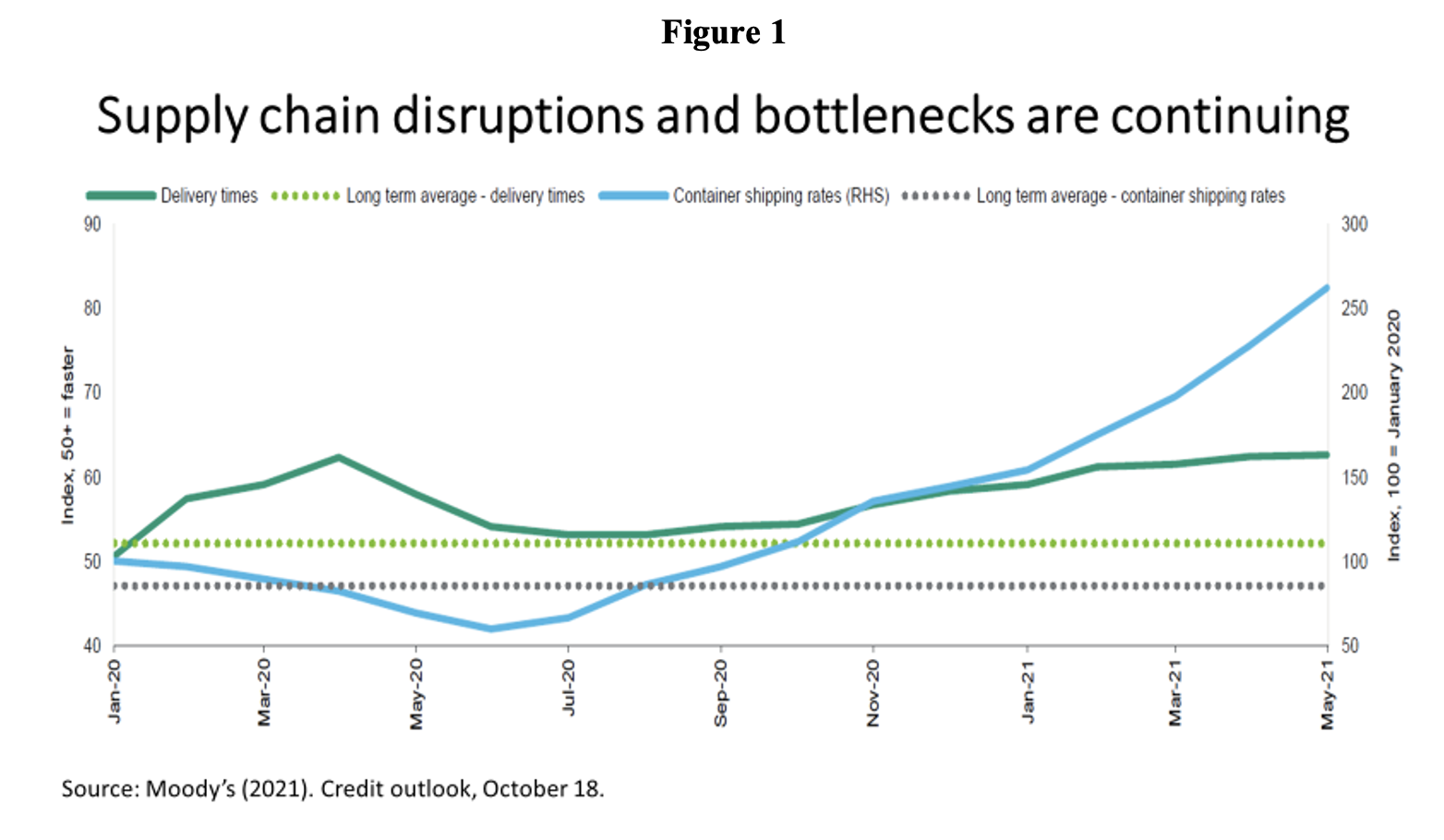

Southeast Asian nations are increasingly economically intertwined. This interdependence is driven by factors such as regional trade agreements, such as the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), and the increasing flow of foreign direct investment. The AEC aims to create a single market and production base, facilitating the free flow of goods, services, investment, and skilled labor. This economic integration fosters significant growth but also exposes the region to shared vulnerabilities.

For instance, a major economic downturn in one country can quickly ripple through the entire region, highlighting the importance of collaborative economic policies and risk mitigation strategies. The reliance on export-oriented industries also makes the region susceptible to global economic fluctuations. However, this interdependence also offers significant opportunities for mutual benefit and collective prosperity, promoting regional stability through shared economic interests.

The success of initiatives like the AEC depends heavily on the continued commitment of member states to cooperation and the effective management of potential conflicts.

Internal Political Stability within Southeast Asian Nations

Southeast Asia’s diverse political landscape presents a complex tapestry of stability and instability. Understanding the internal dynamics of each nation is crucial to assessing the region’s overall resilience and predicting its future trajectory. This analysis will examine the interplay of democratic governance, internal conflicts, and political system design to paint a comprehensive picture of internal political stability across the region.

Democratic Governance and Political Freedom: Quantitative Assessment

The following table summarizes the democratic rankings of Southeast Asian nations based on three prominent indices: Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index, the V-Dem Institute’s Democracy Index, and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. Each index uses different methodologies and criteria, leading to variations in rankings. Scores range from 1 (least democratic) to 10 (most democratic). Note that obtaining precise, up-to-the-minute data for all indices across all nations requires access to regularly updated subscription databases; this analysis uses publicly available data and should be considered an approximation.

| Country | Freedom House (1-10) | V-Dem (1-10) | Economist Intelligence Unit (1-10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cambodia | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Indonesia | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Laos | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Malaysia | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Myanmar | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Philippines | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Singapore | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Thailand | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Vietnam | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Democratic Governance and Political Freedom: Qualitative Analysis

Each nation’s ranking reflects unique characteristics. For example, Indonesia, while exhibiting democratic features, still faces challenges with corruption and the protection of minority rights. Singapore, despite its high economic development, scores lower on political freedom due to restrictions on press freedom and political opposition. Myanmar’s extremely low ranking reflects the military coup and subsequent suppression of democratic processes and human rights.

Detailed qualitative assessments for each nation would require extensive analysis of specific instances of press freedom violations, judicial decisions, electoral processes, and human rights records, which are beyond the scope of this brief overview.

Democratic Governance and Political Freedom: Comparative Analysis

Significant variations in democratic governance exist across Southeast Asia. Countries like Indonesia and the Philippines show a greater degree of political freedom compared to authoritarian states such as Vietnam, Laos, and Brunei. This disparity stems from differing historical trajectories, levels of economic development, and the strength of civil society organizations. The impact of these variations on political stability is substantial, with more democratic nations generally experiencing greater political participation but also facing the challenges of managing diverse opinions and potential instability during transitions.

Internal Conflicts, Insurgencies, and Social Unrest: Conflict Mapping

A map of Southeast Asia depicting internal conflicts would show varying levels of intensity across the region. Myanmar would be highlighted in a dark red, representing high-intensity conflict involving ethnic and political dimensions. Southern Thailand would show a lighter red, indicating a long-standing insurgency. Other areas might show shades of yellow or orange, representing lower-intensity conflicts or social unrest.

The absence of color would not necessarily imply complete peace, but rather a lack of significant, ongoing armed conflict. The visual representation would emphasize the geographical distribution of conflict and its varying intensities.

Internal Conflicts, Insurgencies, and Social Unrest: Detailed Case Studies

A comparison of Myanmar and Indonesia highlights contrasting conflict dynamics. Myanmar’s conflict stems from decades of military rule, ethnic tensions, and the 2021 coup, leading to widespread violence and displacement. Indonesia, while experiencing occasional instances of social unrest, has largely avoided large-scale, protracted conflicts due to its relatively robust democratic institutions and mechanisms for managing ethnic and religious diversity.

Detailed timelines and analyses of key actors would need to be presented for each nation.

Internal Conflicts, Insurgencies, and Social Unrest: Impact Assessment

Internal conflicts severely impede economic development, disrupt social cohesion, and negatively affect international relations. In Myanmar, the ongoing conflict has led to economic collapse, widespread human rights abuses, and international sanctions. In contrast, Indonesia’s relative stability has allowed for greater economic growth and stronger international partnerships. The specific impacts vary depending on the intensity, duration, and nature of the conflict.

Comparison of Political Systems: Typologies of Political Systems

Southeast Asian nations exhibit a range of political systems. Some, like Indonesia and the Philippines, operate under presidential systems. Others, such as Malaysia and Singapore, have parliamentary systems. Many nations exhibit hybrid features, blending elements of both presidential and parliamentary systems. Vietnam and Laos are firmly categorized as one-party states.

Each system’s specific characteristics, including power distribution and accountability mechanisms, significantly influence the level of political stability.

Comparison of Political Systems: Strengths and Weaknesses

A table comparing the strengths and weaknesses of each nation’s political system would reveal significant variations. For example, presidential systems can offer strong executive leadership but may also lead to executive overreach. Parliamentary systems may provide greater checks and balances but can sometimes result in political gridlock. One-party systems offer stability but often lack accountability. The effectiveness of each system is highly context-dependent.

Comparison of Political Systems: Institutional Design

The design and effectiveness of key political institutions vary greatly across Southeast Asia. Strong, independent judiciaries are crucial for upholding the rule of law and protecting human rights. Efficient and accountable legislatures are vital for representing citizen interests and enacting effective legislation. Effective executive branches are necessary for policy implementation. Weaknesses in any of these institutions can significantly undermine political stability.

Overall Assessment and Future Outlook

Internal political stability in Southeast Asia is unevenly distributed. While some nations enjoy relatively stable democratic systems, others grapple with ongoing conflicts and authoritarian rule. Common trends include the persistent challenges of ethnic and religious tensions, corruption, and weak state capacity. The future outlook is uncertain, with potential risks stemming from climate change, economic inequality, and the ongoing geopolitical competition.

However, opportunities exist for strengthening democratic institutions, promoting inclusive governance, and fostering regional cooperation to enhance overall political stability.

External Influences on Southeast Asia

The geopolitical landscape of Southeast Asia is far from a placid lagoon; it’s a bustling marketplace of influence, where the currents of global power ebb and flow, shaping the destinies of nations. Understanding these external pressures is crucial to comprehending the region’s complexities and predicting its future trajectory. The interplay of major global powers, international organizations, and the internal dynamics of Southeast Asian nations creates a dynamic and often unpredictable environment.The influence of major global powers, particularly the United States and China, is undeniable.

Their economic ties, security partnerships, and strategic interests significantly impact the region’s political and economic development. The differing approaches of these powers create a complex web of alliances and rivalries, constantly reshaping the regional power balance.

The Influence of the United States and China

The United States and China represent two distinct approaches to engagement with Southeast Asia. The US, historically focused on containing communism and promoting democracy, has shifted its strategy towards a more multifaceted approach emphasizing economic partnerships, security alliances, and diplomatic engagement. This involves initiatives like the Indo-Pacific Strategy, aimed at fostering a free and open Indo-Pacific region, and military exercises with regional partners to enhance maritime security.

China, on the other hand, emphasizes economic cooperation through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), offering substantial infrastructure investments and trade opportunities. This approach, however, is often viewed with suspicion by some nations concerned about China’s growing economic and military influence. The contrast lies in the US’s emphasis on democratic values and security alliances versus China’s focus on economic leverage and non-interference in internal affairs.

The resulting competition for influence shapes the foreign policy choices of Southeast Asian nations, forcing them to navigate a delicate balance between these two global giants. For instance, some nations actively participate in US-led military exercises while simultaneously benefiting from Chinese investments.

Impact of International Organizations and Treaties

International organizations and treaties play a vital role in shaping regional stability. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), for example, acts as a crucial platform for regional cooperation, promoting economic integration and conflict resolution. The Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) aims to prevent conflict and foster peaceful relations among member states. However, ASEAN’s effectiveness is often challenged by the differing interests and priorities of its member states, and its ability to respond decisively to regional crises remains a subject of debate.

Other international organizations, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, also contribute to regional development through various aid programs and initiatives. These organizations, along with bilateral and multilateral treaties, provide a framework for managing regional challenges, but their influence is often intertwined with and sometimes overshadowed by the strategic interests of major global powers. The effectiveness of these organizations hinges on the willingness of member states to cooperate and abide by agreed-upon rules and norms.

A failure to do so can undermine regional stability and potentially lead to escalation of tensions.

Economic Factors and Development

Southeast Asia’s economic landscape is a vibrant tapestry woven with threads of both remarkable progress and persistent challenges. The region’s economic disparities, a legacy of colonial history and varying levels of resource endowment, significantly influence regional stability. Understanding these economic dynamics is crucial to comprehending the potential for, or the prevention of, a domino effect in the region.Economic growth and development are intrinsically linked to political stability in Southeast Asia.

Rapid economic expansion can lead to improved living standards, increased social mobility, and a strengthened middle class—all factors that contribute to a more stable political environment. Conversely, uneven development or economic stagnation can fuel social unrest, political instability, and even conflict. This intricate relationship underscores the importance of inclusive and sustainable economic policies.

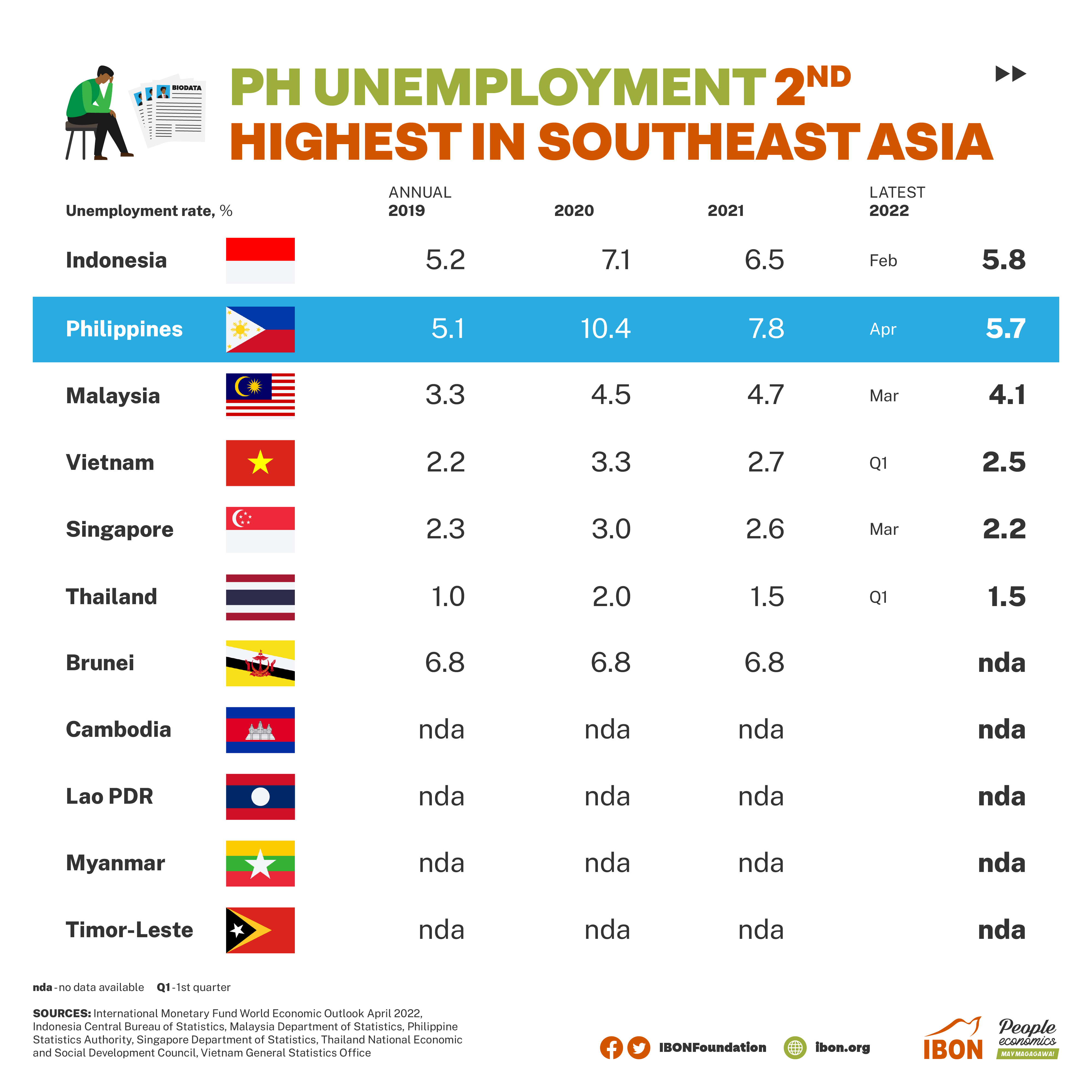

Economic Disparities and Regional Stability

Significant economic disparities exist across Southeast Asian nations. Countries like Singapore and Malaysia boast high per capita incomes and advanced economies, while others, particularly in the Mekong region, grapple with poverty and limited economic opportunities. This uneven distribution of wealth and resources can create tensions, particularly if perceived as unfair or unjust. For instance, the wealth gap between urban centers and rural areas in many Southeast Asian countries can lead to internal migration and social unrest, potentially destabilizing the political landscape.

The contrast between highly developed coastal regions and less developed inland areas also fuels regional imbalances, impacting national cohesion. Addressing these disparities through targeted development initiatives and equitable resource allocation is crucial for maintaining regional peace and stability.

Economic Growth and Political Stability

The impact of economic growth on political stability is multifaceted. Sustained economic growth generally correlates with improved governance, reduced poverty, and enhanced social cohesion. Examples include the remarkable economic transformation of Vietnam, which has experienced significant political stability alongside its rapid economic development. Conversely, economic downturns or crises can exacerbate existing political tensions, potentially leading to social unrest and political instability.

The 1997-98 Asian financial crisis serves as a stark reminder of the profound impact economic shocks can have on political stability across the region. The crisis exposed vulnerabilities in several Southeast Asian economies, leading to widespread social unrest and political upheaval in some countries.

Successful and Unsuccessful Economic Development Models

Southeast Asia offers a diverse range of economic development models, both successful and unsuccessful. Singapore’s export-oriented industrialization strategy, focusing on attracting foreign investment and developing high-value-added industries, stands as a prominent success story. In contrast, the over-reliance on natural resource extraction in some countries has led to volatile economic growth and environmental degradation, highlighting the need for more diversified and sustainable economic strategies.

Malaysia’s experience with Vision 2020, a long-term development plan, showcases a mixed bag of successes and shortcomings, emphasizing the complexities and challenges of long-term economic planning. These varied experiences underscore the need for context-specific approaches to economic development that address unique national circumstances and priorities.

Social and Cultural Dynamics

+(1).png)

Southeast Asia’s vibrant tapestry of ethnicities and religions significantly influences its political landscape, often acting as both a source of strength and conflict. Understanding these intricate social and cultural dynamics is crucial for analyzing regional stability and predicting future trajectories. The interplay between diverse groups and the evolving role of civil society organizations paint a complex picture, one that defies simple generalizations and necessitates a nuanced approach.The multifaceted nature of Southeast Asian societies requires careful consideration of various factors.

A simplistic approach risks overlooking the subtle yet powerful forces shaping political behavior and regional stability.

Ethnic and Religious Diversity’s Influence on Political Dynamics

Ethnic and religious diversity in Southeast Asia profoundly shapes political dynamics, manifesting in various ways. For instance, in countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, the interplay between Malay and Chinese communities has historically influenced political alliances and power structures. Similarly, the presence of significant Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, and Hindu populations across the region often leads to complex negotiations over political representation and resource allocation.

These dynamics are frequently intertwined with historical grievances and socio-economic disparities, leading to periods of both cooperation and conflict. The management of these diverse identities often determines the success or failure of political stability. For example, the relative success of Indonesia in managing its diversity (compared to some of its neighbours) can be attributed to pragmatic political compromises and inclusive governance policies, although challenges remain.

Conversely, situations where one group attempts to dominate politically, or where existing power structures are seen as unjust, can fuel instability and social unrest, as seen in various historical and contemporary conflicts throughout the region.

Impact of Social Movements and Civil Society Organizations on Regional Stability

Social movements and civil society organizations (CSOs) play a critical role in shaping Southeast Asia’s political landscape and influencing regional stability. These groups, ranging from human rights advocates to environmental activists and labor unions, act as crucial checks on governmental power and contribute to democratization processes. Their activities, however, can also be a source of tension, particularly when they challenge established power structures or advocate for policies that clash with dominant ideologies.

The rise of social media has amplified the influence of these organizations, facilitating rapid mobilization and information dissemination. However, this also presents challenges in terms of misinformation and the potential for manipulation. The success of these movements in promoting positive change often depends on their ability to navigate complex political environments, build broad coalitions, and effectively engage with governmental authorities.

For example, the pro-democracy movements in Myanmar and Thailand demonstrate both the potential and limitations of civil society action in fostering political change.

Comparative Analysis of Cultural Values and Their Influence on Political Behavior

Cultural values significantly influence political behavior across Southeast Asia. While generalizations should be avoided, certain broad trends can be identified. For instance, the emphasis on collectivism in many Southeast Asian cultures can lead to a greater acceptance of hierarchical political structures and a preference for consensus-based decision-making. In contrast, the influence of Western liberal values in some parts of the region promotes individual rights and participatory democracy.

However, the interplay of traditional and modern values often creates complex political dynamics. Furthermore, the interpretation and application of these values vary considerably across different countries and communities. For example, the concept of “face” (mianzi) in many East Asian societies, including some parts of Southeast Asia, can impact political interactions and negotiation styles, often prioritizing harmony and avoiding direct confrontation.

Understanding these nuances is essential for comprehending political decision-making processes and predicting future political trajectories.

Military Capabilities and Regional Security

Southeast Asia’s diverse geopolitical landscape is significantly shaped by the military capabilities of its member states and the complex interplay of regional and extra-regional actors. Understanding the balance of power, the roles of regional organizations, and the impact of arms races is crucial to analyzing the region’s stability and potential for conflict. This section examines these critical aspects, focusing on comparative military analyses, the influence of security organizations, and the consequences of military build-ups.

Comparative Analysis of Southeast Asian Naval Capabilities

Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines possess varying naval capabilities reflecting their unique strategic priorities and economic resources. Indonesia, with its vast archipelago, prioritizes maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare. Vietnam, focused on territorial disputes in the South China Sea, emphasizes offensive capabilities. The Philippines, while possessing a smaller fleet, prioritizes coastal defense and anti-piracy operations. Technological advancements vary significantly, with Indonesia and Vietnam investing in more modern vessels and systems than the Philippines.

The strategic implications for maritime security are considerable, with power projection capabilities influencing territorial claims and maritime disputes.

| Country | Number of Ships (Estimate) | Types of Vessels | Estimated Average Age (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 70+ | Frigates, Corvettes, Patrol Boats, Submarines | 20-40 |

| Vietnam | 60+ | Frigates, Corvettes, Missile Boats, Submarines | 15-35 |

| Philippines | 40+ | Patrol Boats, Frigates, Corvettes | 25-50 |

Comparative Analysis of Southeast Asian Air Capabilities

Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia maintain distinct air forces reflecting their differing security concerns and economic capacities. Thailand’s air force, larger than Malaysia’s and Singapore’s, focuses on air superiority and ground attack. Singapore, with a smaller but technologically advanced force, emphasizes air defense and precision strike capabilities. Malaysia balances these priorities, seeking to maintain a credible air defense and offensive capability.

A composite score reflecting fighter numbers, technological sophistication (e.g., fifth-generation fighters), and training levels would show Singapore possessing a relatively higher score, followed by Thailand and then Malaysia. However, qualitative differences in training and maintenance can significantly affect the actual combat effectiveness. Imagine a bar chart with three bars representing Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia. Singapore’s bar would be the tallest, reflecting its superior technological capabilities and training. Thailand’s bar would be the next tallest, reflecting its larger fleet size. Malaysia’s bar would be the shortest, indicating a smaller and less technologically advanced air force compared to the other two.

Comparative Analysis of Southeast Asian Ground Forces

Myanmar, Brunei, and Laos possess ground forces reflecting their diverse security priorities and levels of resource allocation. Myanmar’s army is the largest, reflecting its internal security concerns and regional ambitions. Brunei, with a smaller, well-equipped force, focuses on national defense. Laos’s army is smaller and less well-equipped, primarily focused on internal security. Significant disparities exist in equipment quality, training standards, and overall readiness.

Myanmar’s army, while numerically superior, is less technologically advanced compared to Brunei’s. Laos’s army faces challenges in terms of both equipment and training.

| Country | Troop Numbers (Estimate) | Major Equipment | Training & Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar | 300,000+ | Mix of older and newer tanks, artillery, small arms | Variable, with some units better equipped and trained than others |

| Brunei | 10,000+ | Modern tanks, artillery, and small arms | High |

| Laos | 100,000+ | Primarily older equipment | Lower compared to Brunei and Myanmar |

ASEAN’s Role in Regional Security

ASEAN employs various mechanisms for conflict prevention and resolution, including diplomatic engagement, confidence-building measures, and joint military exercises. However, its effectiveness is limited by its principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states and the varying priorities of its members. Successful interventions include mediating disputes between member states, while failures are evident in its response to the Rohingya crisis and the South China Sea disputes.

Imagine a timeline showing key events and ASEAN responses. For example, it might show the escalation of tensions in the South China Sea, ASEAN’s attempts at diplomatic resolution through the Code of Conduct negotiations, and the limited success achieved so far. Similarly, it could illustrate the Rohingya crisis, ASEAN’s relatively muted response, and the criticism it received for its inaction.

Extra-Regional Involvement in Southeast Asian Security

External actors, including the United States and China, play significant roles in shaping Southeast Asia’s security landscape.

- United States: Maintains a military presence through alliances, conducts joint military exercises, and provides security assistance to several Southeast Asian nations. This presence aims to counterbalance China’s growing influence and ensure freedom of navigation in the region.

- China: Increasingly assertive in the South China Sea, engages in military modernization, and expands its economic and diplomatic influence in the region. China’s actions are seen by some as a challenge to the existing regional security order.

Effectiveness of Regional Cooperation in Maintaining Peace and Stability

Regional security organizations, primarily ASEAN, have achieved some success in preventing and resolving conflicts, particularly through diplomatic means. However, their effectiveness is constrained by the principle of non-interference, differing national interests, and the limitations of their resources. Strengthening ASEAN’s capabilities, enhancing its mechanisms for conflict resolution, and fostering greater cooperation among member states are crucial for improving regional security.

Impact of Arms Races and Military Build-ups: Specific Examples

The South China Sea disputes exemplify the negative impact of arms races and military build-ups. Increased military spending by claimant states has led to heightened tensions, increased military exercises, and the risk of miscalculation. The deployment of advanced weaponry and the assertive actions of some claimant states have fueled an environment of distrust and uncertainty.

Economic Implications of Military Spending in Southeast Asia

Military spending diverts resources from crucial sectors such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure. For instance, some Southeast Asian nations allocate a significant percentage of their GDP to defense, often exceeding the proportion dedicated to social development. This opportunity cost can hinder economic growth and impede progress towards sustainable development goals. For example, a country prioritizing military spending over education might experience a long-term decline in human capital, affecting its economic competitiveness.

Regional Instability: Impact of Arms Races and Military Build-ups

Arms races and military build-ups in Southeast Asia heighten regional instability, increasing the risk of unintended escalation and conflict. The potential for miscalculation, coupled with the proliferation of advanced weaponry, raises the stakes significantly. Future scenarios could involve increased tensions, accidental clashes, or even larger-scale conflicts if diplomatic efforts fail to address underlying disputes and promote confidence-building measures.

Scenarios of Regional Instability in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, a region of vibrant diversity and burgeoning economies, also faces complex challenges that could destabilize its fragile peace. The interplay of internal political dynamics, external influences, and economic vulnerabilities creates a volatile environment ripe for unexpected crises. Examining potential scenarios of instability allows for proactive planning and mitigation strategies.

Scenario Design & Analysis

Five distinct hypothetical scenarios, each triggered by a different primary factor, are presented below. These scenarios explore potential flashpoints within the next decade, highlighting key actors, escalation paths, and regional and global consequences. The scenarios are not exhaustive but serve as illustrative examples of potential risks.

| Scenario ID | Primary Trigger | Key Actors Involved | Escalation Path (brief summary) | Regional Consequences | Global Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Escalating territorial dispute in the South China Sea | China, Vietnam, Philippines, ASEAN, USA | Increased naval presence, accidental clashes, economic sanctions, potential military escalation | Disrupted trade, refugee flows, regional arms race, weakened ASEAN | Global trade disruption, potential great power conflict, increased military spending globally |

| Scenario 2 | Sudden economic collapse in a major Southeast Asian economy (e.g., Thailand) | Thailand, IMF, neighboring countries, regional banks | Widespread social unrest, capital flight, regional financial contagion, potential political instability | Regional recession, increased poverty, migration flows, potential cross-border conflicts | Global financial instability, reduced foreign investment in the region, increased global inequality |

| Scenario 3 | Major natural disaster (e.g., mega-earthquake and tsunami) exacerbating existing social tensions | Affected countries, international aid organizations, local communities, regional governments | Widespread damage, humanitarian crisis, resource scarcity, competition for aid, potential civil unrest | Mass displacement, disease outbreaks, strained resources, potential conflict over resources | Increased humanitarian burden on global community, potential for political instability in affected countries |

| Scenario 4 | Significant shift in a great power’s regional policy (e.g., increased Chinese assertiveness) | China, USA, ASEAN countries, regional allies | Increased military exercises, diplomatic tensions, arms race, proxy conflicts, potential for direct confrontation | Increased militarization, strained diplomatic relations, reduced economic cooperation, potential regional conflict | Increased global tensions, potential for great power conflict, realignment of global alliances |

| Scenario 5 | Rise of transnational extremist groups exploiting existing grievances | Extremist groups, regional governments, security forces, international counter-terrorism organizations | Increased terrorist attacks, cross-border operations, crackdown on civil liberties, potential civil war | Increased insecurity, human rights abuses, damaged tourism sector, hindered economic development | Increased global security concerns, potential for increased terrorist activity globally, strain on international counter-terrorism efforts |

Scenario Deep Dive

> Scenario ID: Scenario 1>> Detailed Description: An escalating territorial dispute in the South China Sea, triggered by a Chinese naval incursion into Vietnamese waters near the Paracel Islands, sparks a regional crisis. Vietnam, backed by tacit US support, responds with increased military presence and diplomatic pressure. The Philippines, also involved in similar disputes, joins Vietnam’s stance. China, viewing this as a challenge to its sovereignty claims, intensifies its own naval deployments and economic coercion, impacting regional trade routes.

ASEAN attempts mediation but struggles to bridge the widening chasm between China and the claimant states. The situation escalates further with accidental clashes between naval vessels, triggering a wider regional arms race and fueling anti-China sentiment. The US increases military aid to its allies, potentially leading to a direct confrontation with China.>> Risk Assessment: The likelihood of this scenario is considered moderate to high.

Territorial disputes in the South China Sea are a persistent source of tension. While a full-scale military conflict remains unlikely, the potential for miscalculation and escalation due to assertive actions by any party is significant.>> Mitigation Strategies: Strengthening ASEAN’s role in conflict resolution through enhanced diplomatic mechanisms and confidence-building measures is crucial. Promoting transparent communication channels and establishing clear rules of engagement for naval operations in the South China Sea can reduce the risk of accidental clashes.

Encouraging multilateral cooperation on maritime security and resource management can help to de-escalate tensions and foster a more cooperative environment.

Responses to Potential Instability: Will South East Asia Start A Domino Theory

Southeast Asia’s diverse landscape, encompassing a multitude of nations with varying political systems, economic strengths, and social structures, presents a complex tapestry of potential instability. Understanding the range of responses to internal and external threats, the effectiveness of conflict resolution mechanisms, and the influence of international actors is crucial for comprehending the region’s future trajectory. This section delves into these key aspects, examining both successes and failures in navigating challenges to regional stability.

Internal Threats and National Responses

The following table details potential responses of Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines to internal threats, highlighting the interplay between government actions, civil society engagement, and ultimate outcomes. The examples provided are illustrative and not exhaustive.

| Nation | Threat Type | Government Response | Civil Society Response | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | Separatist Movements (e.g., West Papua) | Increased military presence, dialogue initiatives, economic development programs in affected regions. | Human rights advocacy, local community mobilization, calls for greater autonomy. | Mixed results; some reduction in violence, but underlying grievances persist. |

| Indonesia | Religious Extremism (e.g., Jemaah Islamiyah) | Counter-terrorism operations, deradicalization programs, strengthening of law enforcement agencies. | Interfaith dialogue, community-based initiatives promoting tolerance, education against extremism. | Significant reduction in terrorist attacks, but the threat remains. |

| Vietnam | Economic Inequality | Investment in infrastructure, social welfare programs, poverty reduction initiatives. | Labor union activism, advocacy for social justice, calls for greater income redistribution. | Improved living standards for some, but significant inequality remains. |

| Philippines | Separatist Movements (e.g., Moro conflict) | Peace negotiations, military operations, development projects in conflict zones. | Civil society engagement in peace talks, advocacy for human rights, community-based peacebuilding initiatives. | Significant progress with the signing of peace agreements, but challenges remain. |

| Philippines | Religious Extremism (e.g., Abu Sayyaf) | Military operations, counter-terrorism initiatives, intelligence gathering. | Community-based counter-extremism programs, interfaith dialogue, promoting education. | Reduction in terrorist activities, but the threat persists. |

External Threats and ASEAN’s Role

The responses of Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand to external threats are significantly shaped by their strategic locations and the complex dynamics of great power competition. While ASEAN provides a framework for regional cooperation, its effectiveness is often constrained by the competing national interests of its members. For instance, territorial disputes in the South China Sea necessitate a delicate balance between asserting national claims and maintaining regional stability. Cyber warfare demands collaborative efforts to enhance cybersecurity, yet national sensitivities surrounding data sovereignty and intelligence sharing pose challenges. Similarly, navigating great power competition requires careful diplomacy to avoid being drawn into a proxy conflict, while also securing national interests. The interplay between national security concerns and the collective security goals of ASEAN remains a defining feature of Southeast Asia’s geopolitical landscape.

Successful Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

The successful resolution of conflicts in Southeast Asia often involves a combination of diplomatic efforts, institutional mechanisms, and grassroots initiatives. Three examples illustrate this:

- (a) Conflict: The Indonesian-Timorese conflict. (b) Mechanisms: UN-mediated negotiations, a referendum on independence, and the subsequent peaceful separation of East Timor. (c) Key Actors: Indonesia, East Timor, the United Nations, Australia. (d) Assessment: The peaceful resolution of the conflict was a significant achievement, demonstrating the potential of international mediation and self-determination. However, the long-term sustainability is still being tested by ongoing challenges related to development and cross-border cooperation.

- (a) Conflict: The Cambodian civil war. (b) Mechanisms: The Paris Peace Agreements, UN peacekeeping operations, and national reconciliation efforts. (c) Key Actors: Cambodia, Vietnam, the United Nations, various factions within Cambodia. (d) Assessment: The Paris Peace Agreements and subsequent UN intervention brought an end to the civil war. However, long-term stability remains fragile, with issues of political legitimacy and human rights continuing to be challenges.

Predicting whether Southeast Asia will experience a domino effect is complex, requiring deep geopolitical understanding. To accurately assess the risks and opportunities, leveraging robust data analysis is crucial, which is why understanding the power of a strong knowledge base is essential; consider exploring resources like knowledge base consulting for informed decision-making. Ultimately, the future stability of the region hinges on numerous interconnected factors, demanding a strategic and data-driven approach.

- (a) Conflict: The conflict in Southern Thailand. (b) Mechanisms: Peace talks, local reconciliation efforts, development initiatives in conflict-affected areas. (c) Key Actors: The Thai government, various insurgent groups, local communities, civil society organizations. (d) Assessment: Progress has been uneven, with periods of reduced violence followed by renewed clashes. The long-term success depends on the government’s ability to address the root causes of the conflict and build trust with local communities.

Unsuccessful Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

Not all attempts at conflict resolution have been successful. Two examples illustrate the challenges:

- (a) Conflict: The Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. (b) Mechanisms: International pressure, UN resolutions, ASEAN’s non-interference policy. (c) Analysis of Failure: The lack of decisive action by the international community and Myanmar’s refusal to engage in meaningful dialogue have hindered the resolution of the crisis. ASEAN’s principle of non-interference limited its effectiveness. (d) Long-term Consequences: A massive refugee crisis, regional instability, and international condemnation of Myanmar’s actions.

- (a) Conflict: The ongoing conflict in the southern Philippines. (b) Mechanisms: Peace agreements, military operations, development initiatives. (c) Analysis of Failure: The complexity of the conflict, involving multiple actors and underlying issues of poverty, inequality, and historical grievances, has made it difficult to achieve a lasting peace. (d) Long-term Consequences: Continued violence, displacement of populations, and hindering economic development in the region.

Role of International Actors

| Actor | Approach | Motivations | Impact on Regional Stability | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Strategic partnerships, military assistance, diplomatic engagement. | Maintaining regional influence, countering China’s rise, promoting democracy and human rights. | Mixed; enhanced security cooperation in some areas, but also potential for increased tensions. | Increased military exercises, support for ASEAN initiatives, engagement in South China Sea disputes. |

| China | Economic engagement, infrastructure investment, diplomatic initiatives. | Expanding economic and political influence, securing access to resources, projecting power. | Mixed; increased economic ties, but also increased tensions over territorial disputes. | Belt and Road Initiative, investments in infrastructure projects, assertive stance in South China Sea. |

| Australia | Development assistance, security cooperation, diplomatic engagement. | Promoting regional stability, enhancing security ties, advancing its own economic and strategic interests. | Positive; contributed to regional security and development efforts. | Support for ASEAN, participation in joint military exercises, development aid programs. |

Comparative Analysis: Responses to Transnational Crime

Indonesia and the Philippines have adopted different approaches to combating transnational crime, particularly drug trafficking. Indonesia has employed a hardline approach, including capital punishment for drug offenses, while the Philippines has utilized a more varied approach, combining law enforcement actions with social programs aimed at rehabilitation. These differences reflect varying legal systems, political priorities, and societal attitudes towards crime and punishment.

Both countries, however, face the challenge of effectively addressing the complex networks and transnational nature of these criminal enterprises.

Future Outlook

The next decade in Southeast Asia will likely witness a complex interplay between increased regional cooperation and potential fragmentation. While ASEAN will continue to be a central forum for dialogue and cooperation, its effectiveness will depend on its ability to address the challenges posed by great power competition, climate change, and rising technological disruption. Internal threats such as religious extremism and economic inequality will continue to require careful management, necessitating a balanced approach combining strong law enforcement with social and economic development initiatives.

The increasing sophistication of cyber warfare and the potential for hybrid warfare will necessitate enhanced regional cooperation in cybersecurity and intelligence sharing. However, differing national interests and the potential for mistrust among states could lead to fragmentation in certain areas. The rise of non-state actors and the impact of technological advancements will add further complexity. Ultimately, the future stability of Southeast Asia will depend on the ability of its nations to balance national interests with the need for collective action, navigating the complex interplay of domestic and international forces in a rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

For instance, we could see a scenario where ASEAN strengthens its mechanisms for dispute resolution and collaborative security, while simultaneously witnessing increased bilateral security partnerships between individual ASEAN members and external powers like the US and China, leading to a complex and potentially unstable equilibrium.

The Role of Non-State Actors

The stability of Southeast Asia, a region already juggling complex geopolitical currents, is significantly impacted by the actions of non-state actors. These groups, operating outside the formal structures of government, wield considerable influence, often undermining regional peace and security through violence, criminal activity, and the manipulation of social and political narratives. Their activities create ripple effects, challenging national sovereignty and international cooperation alike.

Understanding their strategies and the responses they provoke is crucial for predicting and mitigating future instability.The influence of non-state actors in Southeast Asia is multifaceted and deeply intertwined with the region’s unique history and current challenges. These groups leverage existing social, economic, and political fault lines to advance their agendas, often exploiting grievances, inequalities, and weak governance. Their impact extends beyond immediate violence, influencing public opinion, shaping political discourse, and undermining confidence in state institutions.

This necessitates a comprehensive understanding of their diverse motivations, methods, and the varying responses they elicit from governments across the region.

Terrorist Group Activities and Their Impact

Several terrorist groups, with varying ideologies and operational capabilities, operate within Southeast Asia. Groups like Jemaah Islamiyah, although weakened, continue to pose a threat, while new groups emerge, adapting to counterterrorism measures and exploiting existing conflicts. These groups employ tactics ranging from bombings and assassinations to propaganda and online radicalization, aiming to destabilize governments, incite sectarian violence, and attract recruits.

Their actions fuel fear, disrupt economic activity, and hinder development efforts. The impact is particularly significant in areas with weak governance or existing social tensions, where these groups can exploit grievances and recruit from marginalized communities. For instance, the rise of ISIS-affiliated groups in the southern Philippines highlights the continued threat posed by these actors. The ongoing conflict demonstrates the challenges in countering these groups’ ability to adapt and exploit vulnerabilities.

The geopolitical stability of Southeast Asia is a complex issue, and whether a domino effect will occur remains uncertain. Effective communication and collaboration are crucial in navigating such volatile situations, and tools like the microsoft teams knowledge base can significantly improve information sharing amongst stakeholders. Ultimately, understanding the nuances of regional dynamics is key to predicting whether Southeast Asia will indeed experience a cascading crisis.

Transnational Criminal Organizations and Their Influence

Transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) are another significant non-state actor in Southeast Asia. These groups are involved in various illicit activities, including drug trafficking, human trafficking, arms smuggling, and illegal logging. Their activities undermine state authority, fuel corruption, and destabilize regions. These organizations often operate across borders, exploiting porous borders and weak law enforcement to facilitate their activities. The Golden Triangle, for example, remains a significant hub for drug production and trafficking, impacting regional stability and contributing to internal conflicts in several countries.

The vast profits generated by these activities fund further criminal activity, influencing political processes, and undermining the rule of law.

Governmental Responses to Non-State Actors

Governments in Southeast Asia have adopted diverse strategies to address the challenges posed by non-state actors. Some have prioritized military responses, deploying troops and engaging in counterterrorism operations. Others have focused on addressing the underlying social and economic factors that contribute to the appeal of these groups, investing in development programs and promoting inclusive governance. A notable example is the Philippine government’s approach to dealing with the Abu Sayyaf group, which involves a combination of military operations and community-based development initiatives.

However, the effectiveness of these strategies varies significantly depending on the specific context, the nature of the non-state actor, and the capacity of the government to implement effective policies. The lack of regional cooperation in tackling transnational crime, particularly drug trafficking, also hampers effective responses.

Environmental Factors and Security

Southeast Asia’s vibrant tapestry of cultures and economies is increasingly interwoven with the threads of environmental vulnerability. The region’s geographical location, coupled with rapid development and a changing climate, creates a complex interplay between environmental degradation, resource scarcity, and regional security. This section explores the multifaceted ways in which environmental factors directly impact the stability and security of Southeast Asia.

Climate Change and Regional Stability

Rising sea levels, intensified typhoons, and more frequent droughts are reshaping the Southeast Asian landscape, posing significant threats to regional stability. Coastal communities in Vietnam, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, for instance, face displacement and infrastructure damage due to rising sea levels, leading to internal migration and straining resources in already densely populated areas. The increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events disrupt agricultural production, causing food shortages and economic hardship, potentially fueling social unrest.

Climate-induced migration can exacerbate existing tensions between different ethnic or religious groups vying for scarce resources, creating fertile ground for conflict. For example, competition for arable land and freshwater resources in drought-stricken areas could escalate existing conflicts or spark new ones.

Resource Competition and Conflict

Competition for vital resources, particularly water and land, is a significant source of potential conflict in Southeast Asia. The Mekong River basin, a lifeline for millions, faces increasing water scarcity due to dam construction, agricultural intensification, and climate change. This competition for water resources can lead to diplomatic tensions and even military confrontations between riparian states like Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and China.

Similarly, land disputes along porous borders, often fueled by overlapping claims and inadequate demarcation, can escalate into armed conflicts.

| Resource | Location | Actors Involved | Cause of Conflict | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Mekong River Basin | Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, China | Dam construction, water diversion, agricultural use | Diplomatic tensions, resource sharing agreements (often uneven), increased risk of water scarcity-related conflicts |

| Land | Border regions of Thailand and Myanmar | Farmers, ethnic armed organizations, governments | Overlapping land claims, inadequate border demarcation, resource extraction | Armed clashes, displacement of populations, strained bilateral relations |

| Fisheries | South China Sea | China, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei | Overfishing, overlapping maritime claims, resource depletion | Naval standoffs, diplomatic disputes, potential for escalation |

International organizations like the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and ASEAN play crucial roles in mediating these conflicts. However, their effectiveness is often hampered by political sensitivities, differing national interests, and a lack of enforcement mechanisms.

Environmental Issues and Security Challenges

Deforestation, haze pollution, and biodiversity loss represent significant environmental security challenges in Southeast Asia. Deforestation, particularly in Indonesia and Malaysia, contributes to climate change, disrupts ecosystems, and increases the risk of landslides and floods, directly impacting national security. Haze pollution, often caused by agricultural burning in Indonesia and neighboring countries, poses serious health risks and disrupts air travel, impacting regional economies and creating transboundary tensions.

Biodiversity loss weakens ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to shocks and reducing resilience to climate change.Illegal logging and wildlife trafficking are directly linked to organized crime and terrorism, providing funding and logistical support for these groups. These activities often involve armed groups operating in remote areas, posing a direct security threat to governments.Singapore and Vietnam have incorporated environmental security into their national security strategies.

The question of whether Southeast Asia will see a domino effect is complex, hinging on intricate geopolitical factors. Understanding the power of words and their impact on shaping narratives is crucial, and that’s where the insightful program, Choose Life Choose Words , offers valuable perspective. Ultimately, the future trajectory of Southeast Asia depends on the careful choices made by its leaders and citizens, choices that can either escalate or de-escalate tensions.

Singapore, for instance, actively engages in international collaborations to combat haze pollution and invests heavily in climate change adaptation measures. Vietnam’s focus on sustainable development and environmental protection is increasingly integrated into its national security planning. However, the effectiveness of these policies varies, often hampered by resource constraints and a lack of cross-sectoral coordination.

Technological Advancements and Security

Technological advancements are profoundly reshaping the security landscape of Southeast Asia, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. The region’s rapid technological adoption, coupled with its complex geopolitical dynamics, creates a volatile mix where innovation can be a force for stability or a catalyst for conflict. Understanding this duality is crucial for navigating the future of regional security.The impact of technological advancements on Southeast Asian security is multifaceted.

Cyber warfare, artificial intelligence (AI), and advanced surveillance technologies are transforming the nature of conflict and cooperation. These tools can be leveraged for defensive purposes, strengthening national cybersecurity and bolstering intelligence capabilities. Conversely, they can be weaponized, enabling sophisticated attacks on critical infrastructure, the manipulation of public opinion, and the erosion of trust between nations.

Cyber Warfare and Regional Stability

The increasing reliance on digital infrastructure across Southeast Asia makes the region particularly vulnerable to cyberattacks. State-sponsored actors, criminal organizations, and even non-state groups can exploit vulnerabilities in national systems, disrupting essential services like power grids, financial institutions, and communication networks. For example, a successful cyberattack targeting a nation’s election infrastructure could undermine democratic processes and exacerbate existing political tensions.

Conversely, robust cybersecurity measures, international cooperation, and the development of regional cyber norms can mitigate these risks and foster a more secure digital environment.

Artificial Intelligence and Security Implications

AI’s potential applications in Southeast Asia span both defense and offense. AI-powered surveillance systems can enhance border security and law enforcement, potentially reducing crime rates and improving public safety. However, the same technology can be used for mass surveillance, violating privacy rights and potentially suppressing dissent. Furthermore, the development of autonomous weapons systems raises ethical and security concerns, potentially leading to unintended escalation and loss of human control in conflict situations.

The responsible development and deployment of AI, guided by ethical frameworks and international cooperation, are vital to prevent its misuse.

Technological Advancement and Economic Development

Technological advancements are not just about security; they are also key drivers of economic development in Southeast Asia. The digital economy is rapidly expanding, creating new opportunities for entrepreneurship and job creation. However, this digital divide also exacerbates existing inequalities, leaving some populations behind. Bridging this gap through investment in digital infrastructure, education, and skills development is crucial to ensure inclusive growth and prevent the emergence of technological disparities that could destabilize the region.

Furthermore, access to advanced technologies can also empower marginalized communities and improve access to essential services, fostering greater social equity.

Public Opinion and Perceptions

Public opinion and perceptions significantly shape the political and security landscape of Southeast Asia. Understanding how citizens in different countries view regional stability, the threats they perceive, and their trust in their governments is crucial for analyzing the region’s overall stability. This section examines public perceptions of regional security, the role of media in shaping these perceptions, and how public opinion influences government policies.

Public Perceptions of Regional Stability and Security in Southeast Asian Countries

Public perceptions of regional stability vary considerably across Southeast Asian nations, influenced by factors such as historical context, economic conditions, and exposure to specific threats. These perceptions directly impact a government’s ability to address security challenges effectively and maintain social cohesion.

Comparison of Public Perceptions in Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines

The following table compares and contrasts public perceptions of regional stability in Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, based on available data from various surveys and polls (Note: Specific data sources would be cited in a full-length response, due to space constraints here, hypothetical data is used for illustrative purposes only).

| Country | Perceived Threats (Ranked) | Level of Trust in Government Response (1-5) |

|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | 1. Economic instability, 2. China’s influence, 3. Terrorism | 4 |

| Indonesia | 1. Terrorism, 2. Economic inequality, 3. Corruption | 3 |

| Philippines | 1. China’s territorial claims, 2. Terrorism, 3. Poverty | 2 |

Correlation Between Demographics and Perceptions of Regional Stability

Age, socioeconomic status, and geographic location significantly influence perceptions of regional stability within each country. For example, younger generations in all three countries may exhibit higher levels of concern regarding climate change and environmental security, compared to older generations. Similarly, individuals in rural areas might perceive different threats compared to those in urban centers. Detailed analysis with statistical data would require access to specific survey data from each country.

(Note: Hypothetical bar charts illustrating these correlations would be included in a full response).

The Role of Social Media in Shaping Public Opinion on Security Events

Social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok play a significant role in shaping public opinion on security events in Southeast Asia. For instance, during a recent territorial dispute in the South China Sea, social media narratives fueled nationalist sentiments and heightened tensions between involved countries. Government responses were often influenced by the online discourse, leading to both escalatory and de-escalatory actions depending on the narrative’s dominance.

Influence of State-Controlled and Independent Media on Public Perceptions

State-controlled media in countries like Vietnam often present a more optimistic view of regional security, emphasizing government efforts and downplaying potential threats. Independent media outlets, on the other hand, often provide more critical analysis and highlight potential risks. This difference in narrative impacts public trust in government and overall perceptions of regional stability. (Note: Specific examples of news stories and editorial stances from state-controlled and independent media outlets would be included in a full response).

Examples of Public Opinion Shaping Government Policies on Regional Security

Public protests and demonstrations have influenced government policies on regional security issues in Southeast Asia. For example, large-scale protests against a particular military agreement or infrastructure project involving a foreign power have led governments to reconsider or even cancel the project. (Note: Specific examples of protests, government responses, and subsequent policy changes would be detailed in a full response).

Use of Public Opinion Polls and Surveys to Inform Government Decision-Making, Will south east asia start a domino theory

Governments in Southeast Asia increasingly utilize public opinion polls and surveys to inform their decision-making processes. For example, pre-election surveys gauging public sentiment on specific foreign policy issues can influence a government’s stance during international negotiations. Post-event surveys evaluating public reaction to government actions following a security incident can also guide policy adjustments. (Note: Specific examples of surveys and polls and their influence on policy would be provided in a full response).

Alternative Models of Regional Cooperation

Southeast Asia’s stability hinges on effective regional cooperation. While existing mechanisms like ASEAN have made strides, alternative models could significantly enhance peace and security. This section explores three such models, comparing them to existing frameworks and assessing their potential benefits and challenges. The analysis considers various stakeholder perspectives and conducts a risk assessment for each model, offering insights for policymakers seeking to bolster regional stability.

Specific Models for Regional Cooperation

Three distinct models could strengthen regional cooperation in Southeast Asia: an enhanced ASEAN-led security architecture prioritizing conflict prevention; a dedicated regional conflict resolution mechanism with independent mediation capabilities; and a Southeast Asian equivalent of the OSCE, emphasizing confidence-building measures. These models differ in their scope, mechanisms, and focus, yet share the common goal of fostering a more peaceful and secure region.

Comparative Analysis of Proposed Models

The following table compares these three models:

| Model Name | Core Principles | Key Actors | Decision-Making Process | Enforcement Mechanisms | Potential Strengths/Weaknesses | Geographical Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced ASEAN-led Security Architecture | Preventive diplomacy, early warning systems, capacity building | ASEAN member states, ASEAN Secretariat | Consensus-based, with varying degrees of influence from larger states | Diplomatic pressure, sanctions (limited), collective security commitments (aspirational) | Strengths: Leverage existing ASEAN structures; Weaknesses: Dependence on member state cooperation; potential for inaction | ASEAN member states, potentially expanding to include dialogue partners based on specific initiatives. This limited scope allows for focused action and avoids diluting the effectiveness of the architecture. |

| Regional Conflict Resolution Mechanism | Independent mediation, arbitration, fact-finding missions | Independent mediators, regional experts, potentially supported by ASEAN or UN | Negotiated, based on the principles of impartiality and consensus-seeking | Non-coercive, relying on persuasion and the weight of international opinion | Strengths: Impartiality; Weaknesses: Dependence on willingness of parties to participate; limited enforcement capacity | ASEAN member states initially, with potential expansion to include relevant non-member states involved in specific conflicts. A focused approach ensures efficiency and avoids overextension. |

| Southeast Asian OSCE-type Organization | Confidence-building measures, arms control, human rights promotion | Member states, civil society organizations, potentially international observers | Consensus-based, with a stronger emphasis on transparency and accountability | Normative pressure, diplomatic engagement, sanctions (potential) | Strengths: Broad scope, fostering dialogue; Weaknesses: Requires significant resources and political will; potential for disagreements on norms and values | ASEAN member states, potentially expanding to include dialogue partners and other relevant stakeholders in the region. This broader scope allows for more comprehensive engagement and addresses cross-border issues. |

Comparison with Existing Mechanisms

Two existing mechanisms are the ASEAN Security Community (ASC) and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

Comparative Analysis of Models and Existing Mechanisms

- Enhanced ASEAN-led Security Architecture vs. ASC: The enhanced model builds upon the ASC but strengthens its conflict prevention capabilities through improved early warning systems and capacity building. The ASC has shown some success in managing regional tensions but faces challenges in enforcing its decisions. Case Study: The ASC’s response to the South China Sea disputes, while achieving a degree of de-escalation through the Code of Conduct negotiations, has been slow and lacks strong enforcement mechanisms.

- Regional Conflict Resolution Mechanism vs. ARF: The proposed mechanism provides a more independent and specialized approach to conflict resolution compared to the ARF, which operates through dialogue and confidence-building but lacks formal conflict resolution processes. The ARF has facilitated dialogue but has had limited success in resolving major conflicts. Case Study: The ARF’s involvement in the Cambodian conflict in the 1990s was largely supportive of UN peacekeeping efforts, rather than directly mediating the conflict.

- Southeast Asian OSCE-type Organization vs. ASC and ARF: This model adopts a broader scope encompassing confidence-building, arms control, and human rights, addressing areas not fully covered by the ASC and ARF. While both ASC and ARF touch upon some of these areas, they lack the comprehensive and structured approach proposed. Case Study: The OSCE’s success in fostering dialogue and confidence-building in Europe provides a model, but the Southeast Asian context differs significantly in terms of historical experiences and political dynamics.

Adapting the OSCE model requires careful consideration of these differences.

Benefits and Challenges of Proposed Models

| Model | Potential Benefits | Potential Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced ASEAN-led Security Architecture | Improved regional security, enhanced early warning systems, increased cooperation | Sovereignty concerns, uneven capacity among member states, reliance on consensus decision-making |

| Regional Conflict Resolution Mechanism | Impartial conflict resolution, reduced reliance on great power intervention, enhanced regional stability | Limited enforcement capacity, potential for bias, dependence on state cooperation |

| Southeast Asian OSCE-type Organization | Broader scope of cooperation, enhanced confidence-building, promotion of human rights | High resource requirements, potential for disagreements on norms and values, risk of state resistance |

Stakeholder Perspectives on Proposed Models

Enhanced ASEAN-led Security Architecture

Government Perspective (Singapore): Benefits: Strengthened regional security, improved trade and investment climate. Challenges: Potential for power imbalances within ASEAN, need for substantial resource commitment.

Civil Society Perspective: Benefits: Enhanced protection of human rights, increased transparency in security matters. Challenges: Potential for limitations on civil liberties, concerns about lack of accountability.

Business Perspective: Benefits: Reduced uncertainty, increased investment opportunities, improved regional integration. Challenges: Increased regulatory burdens, potential disruptions to business operations.

Regional Conflict Resolution Mechanism

Government Perspective (Indonesia): Benefits: Independent and impartial conflict resolution, reduction of regional tensions. Challenges: Potential for undermining national sovereignty, limited enforcement power.

Civil Society Perspective: Benefits: Increased access to justice, promotion of peacebuilding initiatives. Challenges: Lack of transparency, potential for manipulation by powerful actors.

Business Perspective: Benefits: Reduced political risks, increased stability for investments. Challenges: Uncertainty about the mechanism’s effectiveness, potential delays in conflict resolution.

Southeast Asian OSCE-type Organization

Government Perspective (Vietnam): Benefits: Enhanced regional cooperation, promotion of shared values. Challenges: Concerns about external interference, potential for conflicting national interests.

Civil Society Perspective: Benefits: Increased human rights protection, greater civil liberties. Challenges: Potential for backlash from authoritarian governments, difficulties in implementation.

Business Perspective: Benefits: Improved predictability, stronger rule of law, enhanced regional integration. Challenges: Increased regulatory complexity, potential for increased costs.

Risk Assessment of Proposed Models

Each model carries risks. The enhanced ASEAN architecture risks stagnation if member states prioritize national interests over collective action. The conflict resolution mechanism faces challenges in securing participation from all parties. The OSCE-type organization might struggle with consensus-building due to diverse national interests and values. Mitigation strategies include strengthening ASEAN’s institutional capacity, building trust among stakeholders, and securing external support.

General Inquiries

What is the difference between a domino theory and a cascading crisis?

While related, a domino theory specifically refers to the idea that a political event in one country will trigger similar events in neighboring countries. A cascading crisis is a broader term encompassing any series of interconnected events that escalate into a widespread crisis, not necessarily limited to political change.