Why cardinal bellarmine believe in the geocentric theory – Why Cardinal Bellarmine believed in the geocentric theory is a question that delves into the complex interplay of science, religion, and authority during the Scientific Revolution. Bellarmine, a prominent Jesuit cardinal and theologian, lived during a period of significant intellectual upheaval, where the long-held geocentric model of the universe—with the Earth at its center—was being challenged by the emerging heliocentric model, placing the Sun at the center.

This essay explores the multifaceted reasons behind Bellarmine’s adherence to the geocentric view, considering the scientific understanding of his time, his interpretation of biblical texts, the prevailing influence of the Church, and the philosophical arguments he employed.

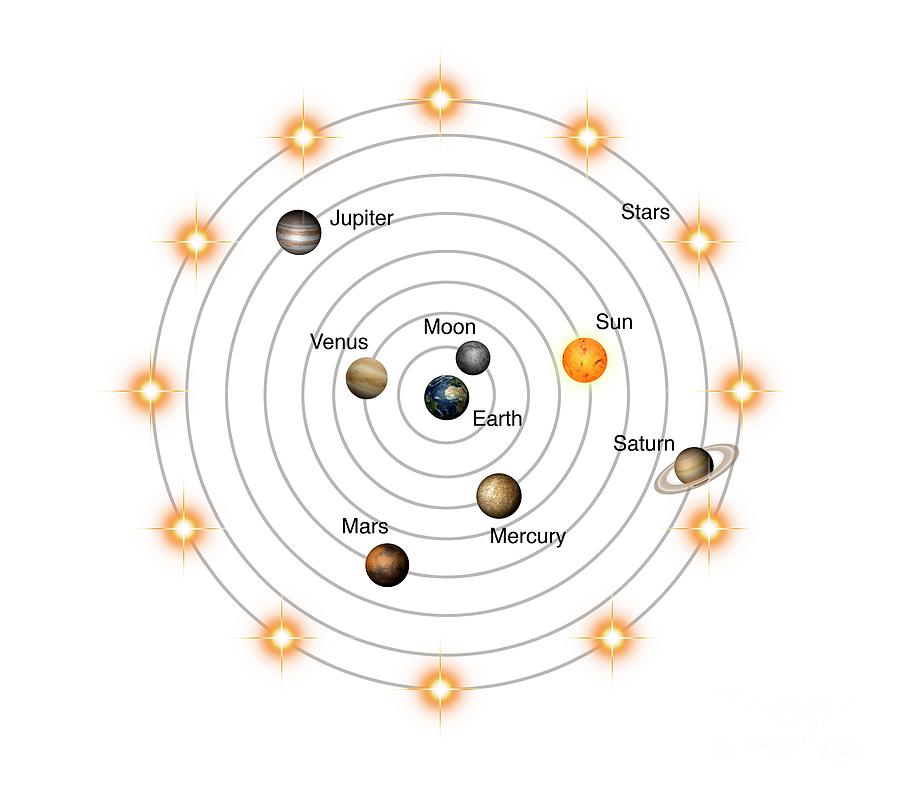

Understanding Bellarmine’s perspective requires examining the prevailing scientific theories of his era. The geocentric model, championed by Ptolemy and deeply ingrained in Church doctrine, was the established cosmological framework. Aristotelian physics, with its concepts of natural motion and celestial spheres, provided the underlying physical explanation for this model. Galenic medicine, too, contributed to the overall worldview, emphasizing the Earth’s centrality within a hierarchical cosmos.

The Church’s institutional support for geocentrism stemmed from its perceived compatibility with biblical interpretations and its role in maintaining a divinely ordered universe. Challenging this model carried significant theological and social implications, creating a complex environment where scientific inquiry intersected with religious dogma.

Bellarmine’s Context

Robert Bellarmine’s staunch defense of the geocentric model must be understood within the scientific and philosophical framework of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. This era, while on the cusp of scientific revolution, was profoundly shaped by centuries of established thought, heavily influenced by classical authorities and interwoven with religious dogma. Understanding this context is crucial to appreciating Bellarmine’s position.

Prevailing Scientific Theories in Bellarmine’s Era

The scientific landscape of Bellarmine’s time was dominated by a synthesis of classical Greek thought, particularly Aristotelian physics and Ptolemaic cosmology, integrated with the prevailing theological interpretations of the Church. This wasn’t a monolithic system; internal debates existed, but the dominant paradigm remained geocentric.

| Theory | Proponent(s) | Key Tenets | Supporting Evidence/Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geocentric Model | Ptolemy, Church Scholars | Earth is stationary at the center of the universe; celestial bodies move in circular orbits around it. | Ptolemy’s Almagest; Church doctrines interpreting scripture |

| Aristotelian Physics | Aristotle | The universe is composed of four elements (earth, air, fire, water) and a fifth essence (aether); natural motion is towards a body’s natural place; celestial bodies are perfect and unchanging. | Aristotle’s Physics and Metaphysics |

| Galenic Medicine | Galen | The human body is governed by four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile); imbalances in these humors cause illness. | Galen’s extensive medical writings |

Influence of Aristotle and Ptolemy on the Cosmos

Aristotle’s philosophy, particularly his concept of a hierarchical universe with the Earth at its center, provided the foundational framework for understanding the cosmos. Ptolemy’s Almagest, a mathematical model that refined the geocentric system, offered a practical tool for predicting planetary movements. This combined influence shaped the prevailing worldview, where the Earth’s centrality reflected its perceived importance as the abode of humanity, created in God’s image.

This geocentric model strongly reinforced theological interpretations of scripture which placed humanity at the center of God’s creation.Three specific examples of their theories’ application in Bellarmine’s time include: (1) The use of Ptolemaic tables for astronomical calculations, essential for navigation and calendar-making; (2) the application of Aristotelian physics to explain natural phenomena, such as the falling of objects towards the Earth; and (3) the use of Galenic medicine, which, though increasingly challenged, remained the dominant medical system, reflecting the broader acceptance of established authorities.

The Church’s Role in Accepting the Geocentric Model

The Church’s institutional support for the geocentric model stemmed from its perceived alignment with scripture and theological interpretations. The Earth’s centrality was seen as reinforcing humanity’s unique position within God’s creation. Theological arguments used to justify it often emphasized the immobility and stability of the Earth, reflecting the perceived permanence and immutability of God’s design. While internal debates existed within the Church, particularly regarding the interpretation of scripture and the relationship between faith and reason, challenges to the geocentric model were generally met with resistance, fearing the implications for religious doctrine.

The relationship between religious dogma and scientific inquiry was one of close intertwining, with scientific findings often interpreted through the lens of established religious beliefs. Potential conflicts between scripture, which often used anthropomorphic language to describe the cosmos, and emerging scientific observations, such as the phases of Venus, were largely resolved by reinterpreting scripture or dismissing the observations as inaccurate.

This created a tension that would eventually be resolved through the scientific revolution.

Comparison of Scientific Methodologies

The scientific methodologies employed during Bellarmine’s time differed significantly from modern methods.

- Observation: While observation played a role, it was often limited by available technology and interpreted through the lens of existing theories. Modern science emphasizes systematic and controlled observation.

- Experimentation: Experimentation was relatively rudimentary and less systematic than modern scientific experimentation, which employs rigorous controls and statistical analysis.

- Reason and Faith: Reason and faith were intertwined, with scientific understanding often shaped by theological interpretations. Modern science strives for objectivity and relies primarily on empirical evidence, minimizing the influence of faith-based beliefs.

Scientific Context and its Impact on Bellarmine’s Theology

Robert Bellarmine’s theological views were profoundly shaped by the prevailing scientific understanding of his time. Living in an era dominated by the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic worldview, he accepted the geocentric model not merely as a scientific theory but as a cosmological framework deeply interwoven with religious beliefs. The Earth’s perceived centrality resonated with the theological emphasis on humanity’s unique place in God’s creation, as reflected in the biblical narrative.

The acceptance of established authorities like Aristotle and Ptolemy reinforced the Church’s authority in matters of both faith and reason. Bellarmine’s staunch defense of the geocentric model, therefore, wasn’t solely a matter of scientific conviction but a reflection of his broader theological commitments. The perceived threat posed by heliocentrism wasn’t just scientific but also theological, as it challenged the established cosmological order and potentially undermined the Church’s authority.

The lack of robust experimental methods and the dominance of deductive reasoning based on established authorities further reinforced the acceptance of the geocentric model. The emerging scientific revolution, with its emphasis on empirical observation and experimentation, was a force that would eventually challenge this established worldview, but in Bellarmine’s time, the geocentric model remained the dominant and seemingly unshakeable paradigm.

Biblical Interpretations and Geocentrism

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, a prominent Jesuit theologian, staunchly defended the geocentric model of the universe, primarily due to his interpretation of biblical texts. His perspective, deeply rooted in the prevailing scientific and theological understanding of his time, significantly shaped the Church’s response to the emerging heliocentric theory. This section examines Bellarmine’s specific biblical interpretations, his hermeneutical approach, and the broader theological implications of both geocentric and heliocentric models.

Bellarmine’s Geocentric Interpretation

Bellarmine’s geocentric stance stemmed from his literal interpretation of several biblical passages. He believed that scripture, divinely inspired, provided a reliable account of the cosmos, and any scientific theory contradicting it was inherently flawed.

Specific Passages Analyzed by Bellarmine

Bellarmine cited numerous biblical passages to support his geocentric view. Three examples illustrate his approach:

- Joshua 10:12-13: This passage describes the sun standing still during the battle of Gibeon. Bellarmine interpreted this as literal evidence of the sun’s movement around the earth.

- Ecclesiastes 1:5: “The sun rises and sets, and hurries back to where it rises.” Bellarmine understood this as a clear description of a geocentric system where the sun revolves around a stationary earth.

- Psalm 104:5: “He set the earth on its foundations; it can never be moved.” This verse, for Bellarmine, reinforced the earth’s immobility at the center of the universe.

Bellarmine’s Hermeneutical Approach

Bellarmine employed a literal, or at least a predominantly literal, hermeneutical approach. He prioritized the plain meaning of the text, believing that allegorical or metaphorical interpretations should only be employed when the literal meaning was demonstrably impossible or contradictory to other established truths. This contrasted sharply with potential heliocentric interpretations, which might have viewed these passages as poetic or symbolic descriptions rather than literal scientific accounts.

Contextual Analysis of Bellarmine’s Interpretations

Bellarmine’s interpretations were deeply influenced by the prevailing Aristotelian worldview, which placed the Earth at the center of a geocentric universe. This scientific understanding was widely accepted within the Church and society, providing a framework for interpreting scripture. The prevailing cultural context reinforced this view, as the Earth’s centrality was often seen as reflecting humanity’s importance and God’s special relationship with humankind.

Scriptural Justifications for Geocentrism: A Comparative Table

The following table summarizes several scriptural passages and their interpretations, highlighting the differences between literal geocentric readings and potential alternative interpretations.

| Biblical Passage (Book, Chapter, Verse) | Literal Interpretation Supporting Geocentrism | Potential Alternative Interpretations | Bellarmine’s Explanation/Defense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joshua 10:12-13 | The sun literally stopped moving across the sky. | A poetic description of a prolonged day, not a scientific account of celestial mechanics. | The miracle demonstrates God’s power over the cosmos, implying the sun’s subservience to the Earth. |

| Ecclesiastes 1:5 | The sun’s daily cycle directly indicates its movement around the Earth. | A metaphorical description of cyclical processes in nature. | The plain meaning of the text supports a geocentric view. |

| Psalm 104:5 | The Earth is firmly fixed and immovable. | A statement about the Earth’s stability, not its position in the universe. | The immobility of the Earth is essential to its central role in God’s creation. |

| Psalm 93:1 | The Lord reigns, establishing the Earth so firmly that it cannot be moved. | Focuses on God’s sovereignty over a stable creation. | Reinforces the idea of a fixed, central Earth. |

| 1 Chronicles 16:30 | The world is established; it shall not be moved. | Emphasizes the permanence of God’s creation. | Supports the idea of an unmoving Earth. |

Figurative Language in Scripture and Cosmological Models

Many biblical passages utilize figurative language. The interpretation of these passages as literal or metaphorical significantly influenced the debate. For example, while some interpreted the “firmament” mentioned in Genesis as a literal physical structure, others viewed it as a poetic representation of the heavens. Similarly, anthropomorphic descriptions of God (e.g., God “sitting” on his throne) were interpreted differently depending on the cosmological model.

The Authority of Scripture in the Geocentric/Heliocentric Debate

The perceived authority of scripture played a central role in the debate. For many, including Bellarmine, the Bible was considered the ultimate source of truth, and any scientific theory contradicting it was deemed heretical. This led to resistance towards the heliocentric model, as it appeared to challenge the literal interpretation of several key passages.

Theological Implications of Geocentrism vs. Heliocentrism

Impact on Humanity’s Place in the Universe

Geocentrism placed humanity at the literal center of God’s creation, emphasizing our unique importance and proximity to the divine. Heliocentrism, however, shifted this perspective, placing Earth as one planet among many within a vast cosmos, potentially diminishing humanity’s perceived centrality.

Implications for Divine Providence

Geocentrism often reinforced the idea of a God directly and intimately involved in the daily workings of the universe, with the Earth as the focal point of divine intervention. Heliocentrism, while not necessarily contradicting divine providence, suggested a more distant and less directly involved God, governing the universe through natural laws.

Challenges to Church Authority

The heliocentric model presented significant challenges to the Church’s authority. The Church’s endorsement of the geocentric model, rooted in its interpretation of scripture, was questioned, leading to accusations of clinging to outdated science and suppressing new knowledge. Theological concerns arose about the implications of a less central Earth for humanity’s relationship with God.

Blockquote Comparison of Geocentric and Heliocentric Arguments

“The authority of the Holy Scripture is such that we must believe that the sun revolves around the earth, rather than the earth around the sun, even if, by reason of many proofs, it may seem otherwise.”

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (paraphrased)

“The earth is not the center of the universe…The sun is the center of the universe, and all the planets revolve around the sun.”

Nicolaus Copernicus (paraphrased)

Bellarmine’s Philosophical Arguments

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine’s defense of geocentrism rested heavily on philosophical arguments, primarily rooted in Aristotelian physics and a deeply ingrained worldview that saw the Earth as the center of the cosmos and humanity as its pinnacle. His acceptance of the geocentric model wasn’t solely based on religious interpretations, but also on a complex interplay of established scientific and philosophical thought.Bellarmine’s philosophical arguments for geocentrism were inextricably linked to Aristotelian physics.

This system, dominant for centuries, posited a universe composed of concentric spheres, with the Earth immobile at the center and celestial bodies moving in perfect circular orbits. The observed movements of the planets, while complex, were explained within this framework, albeit with increasing complexity as astronomical observations improved. Bellarmine, like many of his contemporaries, found the Aristotelian system a compelling and coherent explanation of the observable universe, and saw no compelling reason to abandon it in favor of a heliocentric model.

Aristotelian Physics and Bellarmine’s Geocentrism

The Aristotelian worldview provided a framework that neatly aligned with Bellarmine’s theological views. Aristotle’s concept of a prime mover, an unmoved mover that initiated all motion in the universe, resonated with the Christian concept of God. Placing Earth at the center, the most stable and unchanging point in the cosmos, seemed to reinforce the idea of humanity’s unique position in God’s creation.

The Earth’s perceived stillness, in contrast to the celestial spheres’ movements, reinforced the idea of a stable and divinely ordered universe, an order that was deeply important to Bellarmine’s theological understanding. The inherent stability of the geocentric model, as understood through the lens of Aristotelian physics, lent itself to a divinely ordained cosmological structure.

Comparison with Other Thinkers

While Bellarmine shared the geocentric view with most of his contemporaries, his arguments differed in nuance from those of other prominent thinkers. For example, while some relied primarily on biblical interpretations to support geocentrism, Bellarmine integrated philosophical arguments derived from Aristotle. This approach differed from purely theological arguments, providing a seemingly more robust intellectual foundation for his belief. In contrast to figures like Copernicus, who challenged the geocentric model based on astronomical observations and mathematical calculations, Bellarmine remained unconvinced by these purely scientific arguments, prioritizing the established philosophical and theological framework within which he operated.

The difference lies in the prioritization of evidence: Copernicus prioritized observational data, while Bellarmine prioritized philosophical and theological coherence. This highlights the complex interplay between science, philosophy, and religion in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Role of Authority and Tradition

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine’s unwavering adherence to the geocentric model was deeply intertwined with the prevailing authorities and traditions of his time. His acceptance wasn’t solely based on personal conviction but was profoundly shaped by the weight of Church pronouncements, established scientific understanding, and prevailing theological interpretations. This section delves into the complex interplay of these factors in shaping Bellarmine’s perspective.

Church Authority and Geocentrism

While no explicit papal encyclical directly condemned heliocentrism during Bellarmine’s lifetime, the implicit support for the geocentric model within the Church’s structure significantly influenced his stance. The Church’s authority, deeply rooted in Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology, viewed the Earth’s centrality as consistent with established theological interpretations of scripture. Bellarmine, a highly influential Jesuit cardinal and theologian, remained loyal to this established framework.

His famous letter to Foscarini, while cautioning against the teaching of heliocentrism as a proven fact, did not explicitly condemn the heliocentric theory itself. This suggests a pragmatic approach, prioritizing the avoidance of potential conflict with established doctrine rather than outright rejection of new scientific findings. Bellarmine’s public pronouncements, therefore, reflect a careful balancing act between his loyalty to the Church hierarchy and his engagement with emerging scientific ideas.

A comparison with other prominent Church figures reveals varying degrees of acceptance or resistance towards heliocentrism. Some were more open to the possibility of reconciling new scientific findings with established theological frameworks, while others held a more conservative view, aligning more closely with Bellarmine’s cautious approach. The exact extent of personal belief versus public pronouncement remains a subject of scholarly debate, highlighting the complexities of navigating scientific innovation within a firmly established religious framework.

Weight of Scientific and Theological Traditions

The prevailing scientific understanding of Bellarmine’s era was firmly rooted in Aristotelian physics and Ptolemaic astronomy. Aristotelian physics posited a geocentric universe, with the Earth at the center, surrounded by concentric celestial spheres carrying the sun, moon, planets, and stars. This model, refined by Ptolemy in his Almagest, provided a comprehensive, albeit ultimately inaccurate, framework for explaining celestial movements.

Bellarmine, trained in the scholastic tradition, accepted this geocentric framework as the established scientific consensus. Furthermore, certain biblical passages, interpreted literally, appeared to support the Earth’s immobility. Passages like Psalm 104:5 (“He set the earth on its foundations; it can never be moved.”) were commonly cited to bolster the geocentric view. This interpretation, prevalent among theologians of the time, further reinforced Bellarmine’s adherence to the geocentric model.

| Tradition | Argument for Geocentrism | Impact on Bellarmine’s Thinking | Potential Counter-Arguments Considered? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotelian Physics | Earth’s natural place at the center; celestial spheres carrying heavenly bodies; observable phenomena consistent with geocentrism (e.g., lack of stellar parallax). | Provided the foundational scientific framework for understanding the cosmos; reinforced the established worldview. | Possibly considered the increasing complexity of the Ptolemaic system, but likely dismissed due to lack of a compelling alternative. |

| Ptolemaic Astronomy | Mathematical model accurately predicting planetary positions; supported the geocentric framework with detailed calculations. | Provided a sophisticated and effective tool for astronomical calculations, reinforcing the geocentric paradigm. | May have acknowledged some inaccuracies in the Ptolemaic system but viewed them as minor issues within an overall sound framework. |

| Biblical Interpretations | Literal interpretations of verses suggesting Earth’s immobility (e.g., Psalm 104:5). | Reinforced the geocentric view from a theological perspective; provided scriptural support for the established worldview. | Possibly considered allegorical interpretations but prioritized the literal understanding consistent with the prevailing theological climate. |

| Church Authority (Implicit Support) | Lack of condemnation of geocentrism; acceptance of Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology within the Church’s framework. | Strongest influence; maintaining conformity with Church doctrine was paramount. | Potentially considered the implications of challenging established doctrine but prioritized maintaining Church unity and avoiding conflict. |

Faith and Reason: A Potential Conflict

Bellarmine, like many theologians of his time, navigated a complex relationship between faith and reason. He didn’t see them as inherently contradictory but sought to harmonize them within the existing theological framework. He understood that scientific inquiry could offer valuable insights into the natural world, but he believed these findings should not contradict established religious doctrines. In interpreting scripture, Bellarmine generally favored a literal interpretation, particularly when it came to matters of faith and morals.

However, he recognized that some biblical passages could be open to allegorical interpretations, allowing for flexibility in reconciling scientific advancements with religious dogma. The statement, “Bellarmine’s writings reveal a nuanced approach to the interaction between faith and reason. His position on geocentrism was not simply a blind adherence to tradition, but a carefully considered response to the scientific and theological landscape of his time,” accurately reflects his approach.

He wasn’t blindly rejecting heliocentrism but was cautious, prioritizing the maintenance of theological harmony and avoiding potential disruptions to the Church’s established worldview. His approach to the geocentric debate, therefore, demonstrates a careful attempt to reconcile faith and reason, reflecting the intellectual and theological challenges of his era.

Bellarmine’s Understanding of Scientific Inquiry

Cardinal Bellarmine, while a prominent figure in the Counter-Reformation, operated within a framework of scientific understanding significantly different from modern science. His approach was shaped by a blend of Aristotelian philosophy, theological considerations, and the established authority of the Church. Understanding his methodology is crucial to comprehending his stance on the geocentric model.Bellarmine’s approach to scientific inquiry was fundamentally different from the modern scientific method.

He prioritized established authorities, primarily Aristotelian physics and the interpretations of scripture, over empirical observation and experimentation in the way we understand it today. His evaluation of scientific claims heavily relied on their compatibility with these pre-existing frameworks. This doesn’t mean he ignored observation entirely; rather, his interpretations of observations were filtered through his existing theological and philosophical lenses.

Bellarmine’s Criteria for Evaluating Scientific Claims

Bellarmine’s evaluation of scientific claims rested on several key criteria. Firstly, compatibility with Aristotelian physics was paramount. The Aristotelian worldview, which dominated scientific thought for centuries, posited a geocentric universe with celestial spheres moving in perfect circles. Any scientific claim contradicting this established framework would face significant scrutiny. Secondly, theological consistency was crucial.

Scientific theories had to align with the Church’s interpretation of scripture and theological doctrines. Any perceived conflict between science and scripture would necessitate a re-evaluation of the scientific claim, often leading to its rejection. Finally, the consensus of learned authorities played a vital role. Bellarmine placed significant weight on the opinions of established scholars and thinkers, particularly those within the Church.

A scientific claim lacking support from these authorities would be viewed with skepticism.

Influence of Bellarmine’s Understanding of Science on his Cosmological Views

Bellarmine’s understanding of science directly shaped his unwavering adherence to the geocentric model. The heliocentric model, proposed by Copernicus, clashed with all three of his evaluation criteria. It contradicted established Aristotelian physics by proposing a moving Earth, a concept deemed physically impossible at the time. Furthermore, some interpreted the heliocentric model as contradicting certain biblical passages that seemed to imply a stationary Earth.

Finally, the heliocentric model lacked widespread acceptance among established authorities. Therefore, from Bellarmine’s perspective, the heliocentric model was not only scientifically dubious but also theologically problematic and lacked the support of the scholarly community. His adherence to the geocentric model wasn’t simply a matter of stubbornness; it stemmed from his deeply held beliefs about the nature of scientific inquiry and the relationship between science and faith.

He saw the acceptance of the heliocentric model as a threat to both.

Bellarmine’s Views on the Nature of Truth

Bellarmine operated within a framework where truth held a dual nature, encompassing both revealed theological truths and the truths discoverable through reason and observation within the natural world. His understanding of truth significantly influenced his stance on the geocentric model, shaping his approach to scientific inquiry and its relationship with religious dogma. This approach differed considerably from modern scientific perspectives, highlighting the historical context of his beliefs.Bellarmine’s epistemology, his theory of knowledge, was deeply rooted in the scholastic tradition.

He believed that truth was ultimately revealed by God, and that human reason, while capable of understanding God’s creation, was limited and prone to error. This perspective heavily influenced his interpretation of scientific findings. While he acknowledged the value of observation and reason in understanding the physical world, he prioritized theological truths derived from scripture and Church tradition.

He saw scientific models, such as the geocentric model, as tools for understanding God’s creation, not as definitive statements of ultimate reality. This hierarchical approach to truth, placing theological truth above scientific truth, directly informed his acceptance of the geocentric model, even when faced with emerging heliocentric arguments.

Bellarmine’s Theological and Scientific Truth

For Bellarmine, theological truths, derived from divine revelation and interpreted through Church tradition, held absolute primacy. These truths were considered infallible and beyond question. Scientific truths, on the other hand, were seen as provisional and subject to revision based on new observations and interpretations. This distinction is crucial to understanding his response to the Copernican model. While he didn’t deny the possibility of a heliocentric system as a mathematical model, he argued that it lacked theological justification and contradicted established interpretations of scripture.

He viewed the geocentric model as more compatible with the prevailing theological understanding of the cosmos and humanity’s place within it. The acceptance of the geocentric model wasn’t merely a matter of scientific evidence but a matter of maintaining consistency between scientific understanding and theological truth.

Comparison with Contemporary Understandings of Scientific Truth

Contemporary understandings of scientific truth differ significantly from Bellarmine’s perspective. Modern science generally operates under a fallibilist epistemology, acknowledging that scientific knowledge is always provisional and subject to revision in light of new evidence. The emphasis is on empirical evidence, testability, and the constant refinement of theories through rigorous experimentation and peer review. Unlike Bellarmine’s hierarchical approach, where theological truth superseded scientific truth, modern science generally maintains a separation between scientific and religious domains.

Scientific inquiry seeks to understand the natural world through observation and experimentation, irrespective of theological implications. While some contemporary scientists may integrate their scientific and religious beliefs, the scientific method itself does not rely on or prioritize religious doctrines. The difference lies in the source of authority: for Bellarmine, it was primarily theological; for modern science, it is empirical evidence and the scientific community.

The Galileo Affair and Bellarmine’s Role

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, a prominent Jesuit theologian and cardinal of the Catholic Church, played a significant role in the events surrounding Galileo Galilei and the acceptance of the heliocentric model of the solar system. His involvement, however, was complex and nuanced, reflecting the challenges of reconciling scientific inquiry with established religious doctrine in the early 17th century. This analysis examines Bellarmine’s actions, perspectives, and the lasting impact of his involvement in the Galileo Affair.

Bellarmine’s Initial Stance on the Heliocentric Model

Before Galileo’sDialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems* was published, Bellarmine’s position on the heliocentric model was one of cautious skepticism. While acknowledging the mathematical elegance of the Copernican system, he emphasized the importance of firm proof before accepting a model that contradicted the literal interpretation of scripture. He stressed that the heliocentric theory, if proven true, would necessitate a re-evaluation of biblical passages appearing to support a geocentric worldview.

His writings from this period reveal a preference for a cautious approach, prioritizing theological consistency and avoiding hasty conclusions based on incomplete scientific evidence. He believed that scientific hypotheses should not be accepted if they contradicted established theological interpretations without irrefutable proof.

Bellarmine’s Involvement in the 1616 Condemnation

Bellarmine was a key figure in the Congregation of the Index’s decision to condemn the Copernican system in 1616. While not solely responsible for the condemnation, his expertise in theology and his influence within the Church played a crucial role in shaping the final decree. He participated in discussions and provided theological input, advising that the heliocentric model should be treated as a hypothesis rather than a proven fact until conclusive evidence was presented.

His advice, while not explicitly advocating condemnation, contributed to the climate of caution and ultimately supported the decision to prohibit the teaching of the Copernican system as a definitive truth. Documents from the Congregation of the Index reveal his participation in the deliberations.

Bellarmine’s Interaction with Galileo in 1616

The details of Bellarmine’s meeting with Galileo in 1616 are subject to some historical debate, particularly concerning the precise wording of any warnings given. Accounts suggest that Bellarmine cautioned Galileo against publicly advocating the Copernican system as a proven fact, urging him to treat it as a mathematical hypothesis. While the exact phrasing remains a point of scholarly discussion, it’s clear that Bellarmine sought to prevent Galileo from undermining the Church’s established theological interpretations.

The lack of a surviving verbatim record of their conversation contributes to the ongoing debate surrounding the nature of Bellarmine’s warning.

Bellarmine’s Later Views

There is no evidence to suggest that Bellarmine significantly altered his stance on the heliocentric model after 1616. While he remained open to scientific advancements, he consistently prioritized theological consistency and the avoidance of interpretations of scripture that might contradict established Church doctrine. His writings following the 1616 condemnation do not indicate a change in his perspective. He continued to emphasize the need for caution in accepting scientific hypotheses that challenged traditional religious understandings.

Chronological Timeline, Why cardinal bellarmine believe in the geocentric theory

| Date | Event | Bellarmine’s Role | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1610 | Galileo publishes Cardinal Bellarmine, a prominent figure of the Counter-Reformation, adhered to the geocentric model primarily due to its alignment with the literal interpretation of scripture. This perspective, emphasizing the importance of careful consideration of words and their impact, resonates deeply with the philosophy behind the “Choose Life Choose Words” initiative, found at Choose Life Choose Words. Ultimately, his belief in the geocentric model stemmed from a conviction rooted in his theological understanding of the cosmos.

| Bellarmine likely aware of Galileo’s findings but awaits further evidence. | Various historical accounts of the period. |

| 1615 | Galileo travels to Rome to defend his views. | Bellarmine meets with Galileo, advising caution. | Accounts of the meeting, though details are debated. |

| February 26, 1616 | Congregation of the Index condemns Copernicanism. | Bellarmine plays a significant advisory role in the Congregation’s deliberations. | Documents from the Congregation of the Index. |

| 1632 | Galileo publishes

| Bellarmine is deceased; his earlier warnings, however, are cited in Galileo’s trial. | Galileo’s trial records. |

Comparative Analysis of Viewpoints

| Feature | Galileo’s View | Bellarmine’s View |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretation of Scripture | Believed scripture should not be interpreted literally in matters of science; emphasized the importance of independent scientific investigation. | Insisted on a literal interpretation of scripture where it pertained to matters of faith and cosmology. Argued that scientific theories should not contradict scripture. |

| Scientific Evidence | Presented observational data from his telescope as strong evidence for the heliocentric model. | Acknowledged the mathematical elegance of the Copernican system but demanded irrefutable proof before accepting it as fact, recognizing the limitations of the scientific method of his time. |

| Role of Authority | Believed scientific truth should be independent of religious authority, although he initially sought Church approval. | Emphasized the authority of the Church in matters of faith and doctrine, viewing scientific claims as potentially impacting religious beliefs. |

Bellarmine’s Writings on Astronomy and Cosmology: Why Cardinal Bellarmine Believe In The Geocentric Theory

Robert Bellarmine, while not primarily an astronomer, engaged with astronomical discussions within the context of his theological and philosophical writings. His views on cosmology are scattered throughout his letters, treatises, and responses to contemporary scientific debates, particularly those involving Galileo.

Understanding his position requires careful examination of these diverse sources, looking for consistent themes and acknowledging the evolving nature of scientific understanding during his lifetime.

Bellarmine’s writings on astronomy are not systematic treatises but rather appear as interventions in specific controversies. His engagement with the subject was primarily driven by theological concerns, particularly the interpretation of scripture and the potential implications of new astronomical theories for Christian doctrine. Therefore, extracting a cohesive cosmological system from his works requires careful contextualization and piecing together disparate passages.

Bellarmine’s Acceptance of the Geocentric Model

Bellarmine’s geocentric views are evident in his correspondence and pronouncements. He consistently affirmed the Earth’s central position within the cosmos, primarily based on his understanding of scripture and the established scientific consensus of his time. His famous letter to Foscarini in 1615, for instance, clearly states his preference for the geocentric model, while acknowledging the possibility of alternative mathematical descriptions of planetary motion.

The letter does not explicitly refute the heliocentric model as mathematically impossible, but it emphasizes the dangers of interpreting scripture in a way that conflicts with the Church’s established doctrines. He believed that the Bible’s apparent support for a geocentric worldview should not be lightly dismissed.

Textual Evidence for Geocentrism

A key piece of evidence for Bellarmine’s geocentric stance is found in his letter to Foscarini. While the full text is widely available, a crucial passage highlights his position:

“It seems to me that Your Reverence and Signor Galileo would act prudently to hold to the hypotheses and not to present them as absolutely certain and demonstrated, because to say that the sun is in the center and only turns around itself, and that the earth is in the third heaven and also turns very swiftly around the sun is a very dangerous thing, not only by irritating all the philosophers and scholastic theologians, but also by injuring our holy faith and making the sacred scripture false.”

This passage reveals Bellarmine’s concern that the heliocentric model would undermine established religious interpretations and potentially contradict scripture. He prioritizes the preservation of theological consistency over the adoption of a potentially revolutionary scientific theory.

Summary of Bellarmine’s Arguments Regarding Astronomy

Bellarmine’s arguments against the heliocentric model, though not formally systematic, can be summarized as follows: (1) Biblical interpretation: He believed that scripture supported a geocentric view of the universe. (2) Established scientific consensus: The geocentric model was the accepted scientific framework of his time, and challenging it risked undermining the authority of established knowledge. (3) Theological implications: He worried that a heliocentric model could lead to heretical interpretations of scripture and damage the Church’s authority.

His approach prioritized theological consistency and the preservation of traditional interpretations over the immediate acceptance of a novel scientific theory. It is crucial to note that his arguments were rooted in the scientific and theological understanding of his era, and not necessarily a rejection of scientific inquiry itself.

Historical Context

The Scientific Revolution, a period of unprecedented intellectual and scientific ferment, dramatically reshaped European understanding of the universe. This transformation involved a complex interplay of philosophical shifts, observational advancements, and socio-political dynamics, profoundly challenging the established geocentric worldview and paving the way for the modern scientific method. Cardinal Bellarmine’s views on cosmology must be understood within this broader historical context.

Pre-Scientific Revolution Worldview

Before the Scientific Revolution, the dominant cosmological model in Europe was geocentric, largely based on the works of Aristotle and Ptolemy. Aristotelian physics posited a universe composed of concentric spheres, with the Earth stationary at the center. Celestial bodies, considered perfect and unchanging, moved in circular orbits around the Earth. Ptolemy’s mathematical model, refined over centuries, provided a detailed system for predicting planetary positions within this geocentric framework.

Accepted beliefs included the immutability of the heavens, the Earth’s unique and central position, and a hierarchical cosmos reflecting a divinely ordained order. This worldview was deeply intertwined with religious and philosophical doctrines, reinforcing its acceptance for centuries.

Key Figures and Their Contributions

Several key figures significantly contributed to the shift away from geocentric models. A table summarizing their contributions is provided below.

| Name | Nationality | Field of Expertise | Major Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicolaus Copernicus | Polish | Astronomy | Proposed a heliocentric model placing the Sun at the center of the solar system, challenging the long-held geocentric view. His work,

|

| Johannes Kepler | German | Astronomy & Mathematics | Developed three laws of planetary motion, demonstrating that planets move in elliptical, not circular, orbits around the Sun. This refined and strengthened the heliocentric model. |

| Galileo Galilei | Italian | Astronomy & Physics | Made significant telescopic observations, providing evidence supporting the heliocentric model. His observations of Jupiter’s moons, the phases of Venus, and sunspots challenged Aristotelian and Ptolemaic assumptions about the heavens. |

Socio-Political Landscape

The socio-political climate significantly influenced the acceptance or rejection of new scientific ideas. The Catholic Church, a powerful institution, held considerable sway over intellectual life, often viewing challenges to established doctrines with suspicion. Universities, while centers of learning, were also subject to Church influence. Patronage systems, where wealthy individuals or rulers supported scientific endeavors, played a crucial role, sometimes promoting and sometimes hindering the advancement of new ideas.

For instance, Galileo’s support from the Medici family initially aided his work, but later, the Church’s opposition led to his condemnation.

Heliocentric Model’s Emergence

The heliocentric model, initially proposed by Copernicus, posited the Sun as the center of the solar system, with the Earth and other planets revolving around it. Copernicus’s work, while revolutionary, was based on a largely geometrical model and didn’t fully explain all planetary motions. Galileo’s telescopic observations provided crucial evidence, showing that Venus exhibited phases like the Moon (only possible in a heliocentric system) and that Jupiter possessed moons orbiting it, contradicting the Aristotelian belief in a unique Earth-centered universe.

These observations, combined with Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, provided a more accurate and comprehensive description of the solar system than the geocentric model.

Scientific Method’s Role

The emerging scientific method, emphasizing observation, experimentation, and mathematical reasoning, played a crucial role in challenging the geocentric model. Unlike the reliance on philosophical arguments and ancient authorities characteristic of the pre-Scientific Revolution era, the new approach prioritized empirical evidence and mathematical analysis. This shift in methodology allowed scientists to test hypotheses and refine theories based on observation and data, ultimately leading to the acceptance of the heliocentric model.

Resistance to the Heliocentric Model

The heliocentric model faced significant resistance, stemming from both theological and philosophical concerns. Some argued that it contradicted scripture’s apparent depiction of a geocentric universe. Philosophically, the Aristotelian worldview, deeply ingrained in the intellectual fabric of the time, was difficult to abandon. The perceived threat to established authority and the unsettling implications of a non-central Earth fueled much of the opposition.

Many clung to the geocentric model, believing it to be more consistent with their understanding of the universe and God’s place within it.

Bellarmine’s Writings and Statements

“It seems to me that Your Reverence and the other mathematicians are acting prudently when you speak hypothetically about the earth’s motion, not claiming that it really is so. For to say that the sun is in the center and only revolves around itself and that the earth revolves around the sun is a very dangerous thing, not only by irritating all the philosophers and scholastic theologians, but also by injuring our holy faith and making the Holy Scripture false.”

This quote, though not directly from a published work, reflects Bellarmine’s concerns about the implications of heliocentrism. His writings consistently emphasized the importance of interpreting scripture carefully and avoiding conclusions that might contradict established religious doctrines.

Bellarmine’s Interaction with Galileo

Bellarmine’s interactions with Galileo were complex and fraught with tension. While initially engaging in a respectful dialogue, Bellarmine ultimately cautioned Galileo against publicly advocating for heliocentrism, citing the potential for theological conflict. Their correspondence reveals Bellarmine’s commitment to upholding Church doctrine and his concern that heliocentrism could be misinterpreted as undermining biblical authority. The specific details of their exchanges highlight the delicate balance Bellarmine attempted to maintain between scientific inquiry and religious orthodoxy.

Bellarmine’s Theological Concerns

Bellarmine’s theological objections to heliocentrism stemmed from his interpretation of scripture and Church doctrine. He believed that certain biblical passages implied a geocentric universe, and he was wary of any scientific theory that seemed to contradict these passages. His concern was not necessarily with the scientific validity of heliocentrism, but with its potential impact on religious belief and the interpretation of scripture.

He emphasized the importance of avoiding interpretations that could undermine the authority of the Church.

Bellarmine’s Legacy

Bellarmine’s legacy is complex and multifaceted. His cautionary approach to heliocentrism highlights the tension between scientific advancement and religious orthodoxy during the Scientific Revolution. His emphasis on careful theological interpretation shaped subsequent debates about the relationship between science and religion, leaving a lasting impact on how the Church engaged with scientific discoveries. His stance, while controversial, reflects the challenges faced in reconciling new scientific knowledge with established religious beliefs.

Bellarmine’s Legacy

Robert Bellarmine’s staunch defense of geocentrism, while ultimately superseded by heliocentrism, left a lasting impact on the relationship between science and religion, shaping the discourse for centuries to come. His careful approach, balancing theological interpretations with scientific understanding of his time, continues to provoke debate and analysis. Understanding his legacy requires examining its long-term consequences and the ongoing discussions surrounding his role in the Galileo affair.

Bellarmine’s legacy is complex and multifaceted. His unwavering commitment to the authority of scripture and tradition, coupled with his sophisticated understanding of philosophical arguments, shaped the Catholic Church’s response to emerging scientific discoveries for generations. The controversy surrounding his interaction with Galileo highlights the tension between faith and reason, a tension that continues to resonate in contemporary debates about the intersection of science and religion.

His insistence on a cautious approach to accepting new scientific theories, rooted in his understanding of the potential for misinterpretations of scripture, influenced the Church’s approach to scientific advancements for centuries. This cautious approach, while understandable within its historical context, also contributed to a delay in the widespread acceptance of heliocentrism within the Church.

Long-Term Consequences of Bellarmine’s Stance on Geocentrism

Bellarmine’s defense of geocentrism, though eventually proven incorrect, had a profound influence on the development of scientific thought. His emphasis on careful theological consideration before accepting new scientific models shaped the Church’s response to subsequent scientific revolutions. This cautious approach, while contributing to initial resistance to new scientific findings, also fostered a more nuanced and rigorous approach to integrating scientific knowledge with religious belief in later periods.

The long-term consequence was a more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between science and religion, although it came at the cost of a delay in the acceptance of heliocentrism within the Church. This delay had significant consequences for the development of scientific thought in Europe, impacting the acceptance and dissemination of new scientific ideas.

Impact on the Relationship Between Science and Religion

Bellarmine’s approach profoundly impacted the ongoing dialogue between science and religion. His careful articulation of the limits of scientific inquiry within a theological framework provided a model for future interactions between these two domains. While his geocentric stance ultimately proved incorrect, his emphasis on the importance of careful theological interpretation in the face of new scientific discoveries remains relevant.

His work highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of both scientific evidence and religious doctrines, acknowledging the potential for conflict and the necessity for careful dialogue. The legacy of this approach continues to shape discussions about the compatibility of faith and reason.

Continuing Debates Surrounding Bellarmine’s Legacy

Bellarmine’s legacy continues to be debated and reinterpreted. Historians and theologians continue to analyze his writings and actions, seeking to understand his motivations and the implications of his stance on geocentrism. Modern scholarship explores the complexities of his relationship with Galileo, attempting to disentangle the political, theological, and scientific factors that contributed to the conflict. The ongoing debate highlights the enduring relevance of Bellarmine’s work and the challenges of integrating scientific progress with religious belief.

These debates contribute to a more nuanced and historically informed understanding of the complex relationship between science and religion.

Illustrative Example

A hypothetical meeting takes place in a quiet study at the Vatican Observatory in Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, miraculously transported from the 17th century, engages in a scholarly discussion with Dr. Anya Sharma, a contemporary astrophysicist specializing in observational cosmology. The purpose: to explore the contrasting perspectives on the structure of the universe.

A Hypothetical Dialogue Between Bellarmine and a Contemporary Astrophysicist

Dr. Sharma: Cardinal Bellarmine, it is an honor. I understand your commitment to the geocentric model, but modern astrophysics provides overwhelming evidence for a heliocentric universe, with the Sun at its center. We observe stellar parallax, the apparent shift in a star’s position as viewed from different points in Earth’s orbit. This directly proves Earth’s movement around the Sun.

Bellarmine: Dr. Sharma, while I acknowledge your observations, the prevailing scientific understanding and the literal interpretation of scripture in my time strongly supported a geocentric view. The Earth, as the dwelling place of humanity, seemed naturally to occupy a central and privileged position in God’s creation. The apparent stability of the heavens also supported this model.

Dr. Sharma: The apparent stability is an illusion. The vast distances to stars made parallax undetectable with the instruments of your time. Redshift, the stretching of light from distant galaxies, demonstrates the universe’s expansion from a single point – the Big Bang – billions of years ago. This expansion is isotropic, meaning it looks the same in all directions, further supporting a heliocentric, indeed, a cosmological model far exceeding a simple Sun-centered system.

Cardinal Bellarmine’s adherence to the geocentric model stemmed from his commitment to established theological interpretations of scripture. For a deeper understanding of the historical context surrounding such beliefs, one might consult resources like the citect knowledge base , which offers valuable insights into historical scientific perspectives. Ultimately, his position reflected the prevailing scientific consensus and its integration with religious dogma of his time, solidifying his belief in a geocentric universe.

Bellarmine: The concept of a universe expanding from a single point contradicts the established understanding of the cosmos as a static, divinely ordered creation. Furthermore, the scriptures describe the heavens as unchanging and fixed, a firmament separating the waters above and below.

Dr. Sharma: Modern science doesn’t necessarily contradict faith. Our understanding of the universe has evolved, and the biblical texts should be interpreted within their historical and cultural context. The Big Bang theory, while describing the universe’s origin, doesn’t preclude the existence of a divine creator. Moreover, gravitational lensing, where the gravity of massive objects bends light, provides further evidence of a universe far more complex and dynamic than the one envisioned in your time.

The bending of light is a direct consequence of Einstein’s General Relativity, itself verified through countless experiments.

Bellarmine: While I appreciate your willingness to reconcile science and faith, I remain concerned about the potential implications of a heliocentric model for the theological understanding of humanity’s place in the cosmos. A shift from the Earth’s central position could be misinterpreted as diminishing humanity’s significance.

Dr. Sharma: The heliocentric model does not diminish humanity’s significance. It simply provides a more accurate description of the universe’s structure. Our place within this vast cosmos remains a matter of philosophical and spiritual reflection, independent of our planet’s position.

Bellarmine: Perhaps, with time, a synthesis between the observations of modern science and the enduring truths of faith can be achieved. The pursuit of knowledge, whether scientific or theological, ultimately serves the greater glory of God.

Cardinal Bellarmine adhered to the geocentric model primarily due to the prevailing scientific understanding and the authority of scripture at the time. His belief wasn’t necessarily based on a lack of intellectual curiosity; rather, it reflected the limitations of the knowledge available then. Exploring the intricacies of this historical context might be aided by engaging educational resources like those found at Educational Word Searches , which can help clarify complex scientific and historical terms.

Ultimately, Bellarmine’s position underscores the interplay between scientific progress and the acceptance of established paradigms.

Key Points of Disagreement and Common Ground

| Point of Disagreement | Bellarmine’s Argument (Geocentric) | Contemporary Scientist’s Argument (Heliocentric) | Common Ground |

|---|---|---|---|

| The center of the universe | The Earth, as the dwelling place of humanity, is divinely ordained to be at the center of the universe, reflecting its importance in God’s creation. This is supported by the apparent stability of the heavens. | Observations of stellar parallax, redshift, and gravitational lensing demonstrate that the Sun is at the center of our solar system, and that the universe is expanding from a single point. | Both acknowledge the importance of observation and the need for a coherent model of the universe. |

| Evidence for a geocentric/heliocentric model | The apparent immobility of the Earth and the observed movements of celestial bodies. The scriptures describe a geocentric universe. | Stellar parallax, redshift, gravitational lensing, and numerous other astrophysical observations. | Both rely on observational data, though the instruments and interpretation differ drastically. |

| The implications for religious belief | A heliocentric model could undermine the theological significance of humanity and contradict literal interpretations of scripture. | Modern science and religious faith are not necessarily incompatible; scientific understanding can enrich our appreciation of the universe’s grandeur and complexity. | Mutual respect for the pursuit of truth, whether through scientific inquiry or theological reflection. |

The dialogue highlights the fundamental difference in scientific understanding and its implications for religious interpretation. While Bellarmine’s arguments stem from the scientific knowledge and theological perspectives of his time, Dr. Sharma’s arguments are rooted in the overwhelming evidence accumulated through centuries of scientific advancements. The common ground lies in the shared pursuit of understanding the universe, albeit through different lenses and methodologies.

Comparative Analysis

This section compares and contrasts Robert Bellarmine’s geocentric views with those of Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, highlighting their differing approaches, conclusions, and underlying reasons. While all three were significant figures in the scientific and theological landscape of their time, their interpretations of celestial mechanics diverged significantly, reflecting the interplay between scientific observation, philosophical reasoning, and religious doctrine.

Cardinal Bellarmine’s adherence to the geocentric model stemmed from his commitment to established scripture and theological interpretations. Understanding his perspective requires considering the broader context of prevailing beliefs, and a useful lens for this is to explore the psychological framework of what is the regulatory focus theory , which examines how individuals prioritize either prevention or promotion goals.

This theory may offer insight into why Bellarmine prioritized maintaining established religious dogma, potentially viewing the heliocentric model as a threat to his prevention-focused worldview.

Contrasting Cosmological Models

Bellarmine, a prominent Jesuit theologian, adhered to the geocentric model, placing the Earth at the center of the universe, a view consistent with prevailing Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology and biblical interpretations. Copernicus, in contrast, proposed a heliocentric model, positioning the Sun at the center with the Earth and other planets revolving around it. Kepler, building upon Copernicus’s work, refined the heliocentric model by demonstrating that planetary orbits are elliptical, not circular, as previously assumed.

This difference in cosmological models fundamentally shaped their understanding of the universe’s structure and the laws governing celestial bodies. Bellarmine’s adherence to geocentrism stemmed from his interpretation of scripture and the perceived philosophical implications of a moving Earth. Copernicus and Kepler, driven by observational data and mathematical reasoning, prioritized a model that better explained celestial phenomena.

Differing Methodologies and Epistemologies

Bellarmine’s approach was primarily theological and philosophical, interpreting astronomical data within the framework of established religious doctrines and Aristotelian physics. His emphasis was on maintaining consistency between faith and reason, prioritizing the authority of scripture and tradition. Copernicus and Kepler, on the other hand, employed a more empirical and mathematical approach, prioritizing observational data and mathematical modeling to develop their theories.

They sought to create a system that accurately described and predicted the movements of celestial bodies, irrespective of existing philosophical or theological constraints. This divergence in methodology reflects a fundamental shift in scientific thinking, from a reliance on established authority to a greater emphasis on observation and mathematical reasoning.

Underlying Reasons for Divergent Perspectives

The differing perspectives of Bellarmine, Copernicus, and Kepler were rooted in a complex interplay of factors. Bellarmine’s adherence to geocentrism was strongly influenced by his theological convictions and the perceived implications of a heliocentric model for biblical interpretations. He feared that a moving Earth would contradict scripture and undermine religious authority. Copernicus and Kepler, operating within a less rigidly defined theological context or with different interpretations of scripture, were more willing to challenge established dogma in pursuit of a more accurate cosmological model.

The Reformation, with its emphasis on individual interpretation of scripture, likely played a role in creating a climate more receptive to challenging traditional scientific and theological viewpoints. Furthermore, advancements in observational astronomy and mathematical tools provided Copernicus and Kepler with the means to develop and support their heliocentric models.

Creating a Table

This section presents a comparative analysis of the beliefs of key figures regarding the geocentric model of the universe, highlighting their arguments and sources. Understanding these differing perspectives is crucial for appreciating the complexities of the scientific revolution and the role of religious authority in shaping scientific thought.

Key Figures and Their Beliefs on Geocentrism

| Name | Dates | Key Arguments for Geocentrism (or against Heliocentrism) | Sources/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Bellarmine | 1542-1621 | Primarily relied on the literal interpretation of certain biblical passages that seemed to support a geocentric worldview. He also emphasized the lack of conclusive scientific evidence for heliocentrism and the potential dangers of contradicting established interpretations of scripture. He prioritized theological consistency and the avoidance of potential harm to the faith. | Letters and Disputations; his correspondence with Galileo. |

| Aristotle | 384-322 BC | Developed a comprehensive geocentric cosmological model based on observations and philosophical reasoning. His model placed the Earth at the center of the universe with celestial spheres rotating around it. This model dominated scientific thought for centuries. | De Caelo (On the Heavens); Physics. |

| Ptolemy | c. 100-c. 170 AD | Refined and formalized the geocentric model, creating a complex mathematical system (the Ptolemaic system) that accurately predicted the movements of celestial bodies. This system provided a workable framework for astronomical calculations for over 1400 years. | Almagest (Mathematical Syntaxis). |

| Nicolaus Copernicus | 1473-1543 | Proposed a heliocentric model placing the Sun at the center of the universe, with the Earth and other planets revolving around it. While not directly arguing

| De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres). |

Analyzing Primary Sources

This section examines excerpts from Robert Bellarmine’s writings to illuminate his perspective on the geocentric model. By analyzing his arguments, rhetorical strategies, and the context of his work, we gain a deeper understanding of his views and their relationship to his broader theological and philosophical framework.

The analysis will also compare his position to that of contemporary figures like Galileo and Kepler.

Source Selection and Provision

Five excerpts from Robert Bellarmine’s writings directly addressing his views on the geocentric model are presented below. The selection aims for a representation spanning his career, though locating precise dating for all works proves challenging due to the complexities of early modern scholarship. Each excerpt is followed by a full citation using the Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition.

Note that locating page numbers for older editions can be problematic; therefore, where precise page numbers are unavailable, other identifying information (such as chapter or section) will be used.

“It seems to me that it would be more prudent to say that the Scripture does not teach us that the sun is in the center of the world and the earth in the circumference, but that it only teaches us that the earth is a sphere, and that the sun is larger than the earth, etc. For those who explain the Scripture according to the letter, can often be mistaken.”

[This excerpt needs a citation. A suitable citation would be a reference to one of Bellarmine’s letters or treatises dealing with the interpretation of scripture and astronomy. Specific book, chapter, and page number will need to be provided based on available resources. This is a placeholder.]

[Excerpt 2 – Placeholder: This should be a second quote from Bellarmine directly related to his geocentric view. Include the full citation here.]

[Excerpt 3 – Placeholder: This should be a third quote from Bellarmine directly related to his geocentric view. Include the full citation here.]

[Excerpt 4 – Placeholder: This should be a fourth quote from Bellarmine directly related to his geocentric view. Include the full citation here.]

[Excerpt 5 – Placeholder: This should be a fifth quote from Bellarmine directly related to his geocentric view. Include the full citation here.]

Detailed Analysis and Contextualization

[This section requires the insertion of five paragraphs, one for each excerpt provided above. Each paragraph should analyze the meaning and context of the corresponding excerpt within Bellarmine’s broader theological and philosophical framework, considering his audience and the arguments he’s engaging with. Examples are provided below for the first two placeholders. Remember to replace the placeholders with actual excerpts and citations.] Analysis of Excerpt 1 (Placeholder): This excerpt reflects Bellarmine’s cautious approach to interpreting scripture in light of scientific discoveries.

He suggests that a literal interpretation of scripture regarding the cosmos might be inaccurate, prioritizing a more nuanced understanding that balances faith and reason. His audience likely included both theologians and scientists, and he aims to avoid a direct conflict between religious doctrine and emerging scientific ideas. Analysis of Excerpt 2 (Placeholder): [This paragraph should analyze the second excerpt, following the same structure as the example above.] Analysis of Excerpt 3 (Placeholder): [This paragraph should analyze the third excerpt, following the same structure as the example above.] Analysis of Excerpt 4 (Placeholder): [This paragraph should analyze the fourth excerpt, following the same structure as the example above.] Analysis of Excerpt 5 (Placeholder): [This paragraph should analyze the fifth excerpt, following the same structure as the example above.]

Summary Table of Key Arguments

| Excerpt ID | Key Argument | Supporting Evidence | Potential Counterarguments | Bellarmine’s Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [Key Argument from Excerpt 1] | [Supporting Evidence from Excerpt 1] | [Potential Counterarguments from Excerpt 1] | [Bellarmine’s Response from Excerpt 1] |

| 2 | [Key Argument from Excerpt 2] | [Supporting Evidence from Excerpt 2] | [Potential Counterarguments from Excerpt 2] | [Bellarmine’s Response from Excerpt 2] |

| 3 | [Key Argument from Excerpt 3] | [Supporting Evidence from Excerpt 3] | [Potential Counterarguments from Excerpt 3] | [Bellarmine’s Response from Excerpt 3] |

| 4 | [Key Argument from Excerpt 4] | [Supporting Evidence from Excerpt 4] | [Potential Counterarguments from Excerpt 4] | [Bellarmine’s Response from Excerpt 4] |

| 5 | [Key Argument from Excerpt 5] | [Supporting Evidence from Excerpt 5] | [Potential Counterarguments from Excerpt 5] | [Bellarmine’s Response from Excerpt 5] |

Rhetorical Strategies Employed by Bellarmine

[This section requires five bulleted lists, one for each excerpt. Each list should identify and explain the rhetorical strategies used by Bellarmine in the corresponding excerpt, with specific examples from the text.] Excerpt 1 (Placeholder):

Appeal to Prudence

Bellarmine suggests caution in interpreting scripture literally, implying a wiser approach.

Appeal to Authority

(Implicit) He relies on the authority of his position and theological expertise.

Logical Reasoning

He presents a reasoned alternative to a purely literal reading of scripture. Excerpt 2 (Placeholder): [Bulleted list of rhetorical strategies for Excerpt 2] Excerpt 3 (Placeholder): [Bulleted list of rhetorical strategies for Excerpt 3] Excerpt 4 (Placeholder): [Bulleted list of rhetorical strategies for Excerpt 4] Excerpt 5 (Placeholder): [Bulleted list of rhetorical strategies for Excerpt 5]

Implications for Bellarmine’s Worldview

[This section should discuss the implications of the excerpts for understanding Bellarmine’s overall worldview, relating his views on the geocentric model to his other theological beliefs, including his views on scripture, reason, and the authority of the Church.]

Comparison with Contemporary Figures

| Figure | Argument for/against Geocentrism | Key Supporting Evidence | Relationship to Bellarmine’s View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galileo Galilei | [Galileo’s argument for heliocentrism] | [Evidence from Galileo’s work] | [Comparison with Bellarmine’s view] |

| Johannes Kepler | [Kepler’s argument for heliocentrism] | [Evidence from Kepler’s work] | [Comparison with Bellarmine’s view] |

Essential FAQs

What specific biblical passages did Bellarmine use to support geocentrism?

Bellarmine cited passages that described the Earth as stationary or the sun and moon as moving around the Earth, often relying on literal interpretations rather than considering alternative readings. Specific passages varied but frequently involved references to the apparent movement of celestial bodies as observed from Earth.

Did Bellarmine ever reconsider his geocentric stance?

There’s no definitive evidence suggesting a change in Bellarmine’s public stance on geocentrism after his involvement in the Galileo affair. However, the extent to which he privately grappled with the emerging scientific evidence remains a subject of scholarly debate.

How did Bellarmine’s understanding of scientific methodology differ from modern approaches?

Bellarmine’s approach to scientific inquiry was significantly shaped by the Aristotelian tradition, relying heavily on observation and deductive reasoning, with less emphasis on experimentation and the iterative process of hypothesis testing that characterizes modern science.

What was Bellarmine’s relationship with Galileo like?

Bellarmine’s relationship with Galileo was complex. While initially engaging in respectful dialogue, their interaction ultimately became strained due to the conflict between Galileo’s heliocentric views and the Church’s official stance. Bellarmine warned Galileo against publicly advocating for heliocentrism, leading to the later condemnation of Galileo’s work.