Who is a valuer in theory of knowledge – Who’s a valuer in Theory of Knowledge? That’s like asking who gets to decide what’s a really, really good pizza – is it the chef, the critic, or the person whose taste buds haven’t been assaulted by pineapple? Turns out, in TOK, “valuer” is way more complex than just someone who slaps a price tag on things.

It’s about understanding how our personal history, cultural baggage, and even our biases influence how we judge the worth of…well, pretty much everything. From vintage photos to the latest tech gadget, this exploration dives deep into the messy, subjective, and sometimes hilarious world of valuation.

We’ll explore the wild west of subjective vs. objective valuation, examine the role of personal experiences and cultural backgrounds (prepare for some seriously skewed perspectives!), and even delve into the ethical minefield of valuation methods. Think of it as a philosophical price-tag-appraisal-detective-story. Buckle up, it’s going to be a bumpy ride!

Defining Valuation in Theory of Knowledge

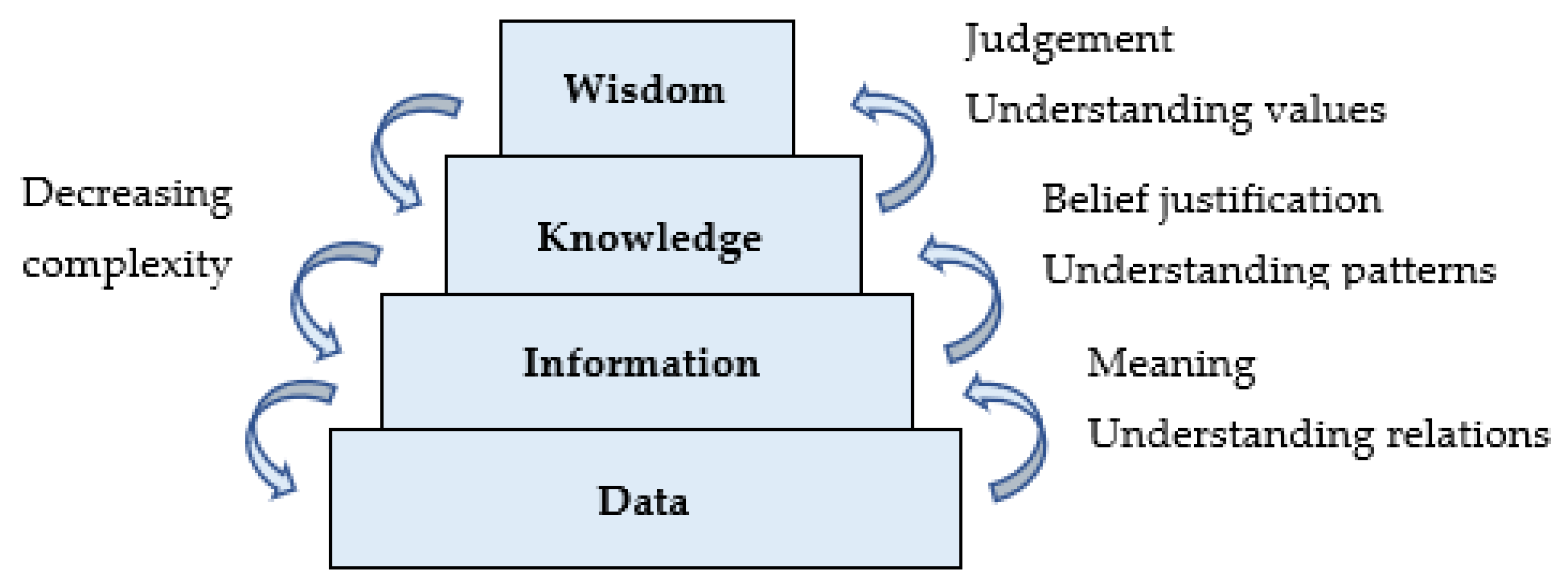

Yo, TOK is all about figuring out how we know what we know, right? But a big part of that is understanding how wevalue* what we know. It’s not just about facts; it’s about what we think is important, true, beautiful, or good. This is where the “valuer” comes in – that’s you, the person making those judgments.A valuer, in the context of TOK, is anyone who assigns worth or importance to something.

It’s about the processes and criteria used to determine the significance of knowledge claims, experiences, and beliefs. It’s super personal, but also influenced by tons of outside factors. Think of it like this: you’re constantly ranking things – what’s more important, your grades or hanging out with friends? That’s valuation in action.

Types of Valuation

Different types of valuation exist, depending on what’s being valued and how. We’re not just talking about money here; we’re talking about all sorts of things – from ethical judgments to aesthetic preferences. Some valuations are based on logic and reason, while others are driven by emotions or personal experiences. For example, valuing a painting based on its artistic merit is different from valuing it based on its monetary worth.

Similarly, valuing a scientific theory based on its empirical evidence is different from valuing it based on its societal impact.

Subjective and Objective Valuation

Subjective valuation is all about personal opinion and perspective. What one person finds valuable, another might find totally irrelevant. Think about music: what one person considers the best song ever, another might find unbearable. This is totally fine! It reflects the individual’s unique experiences, beliefs, and cultural background. There’s no single “right” answer in subjective valuation.

It’s like choosing your favorite flavor of ice cream – there’s no objectively “best” flavor.Objective valuation, on the other hand, aims for a more universal standard. It tries to assess value based on criteria that are, ideally, independent of personal biases. For example, evaluating the effectiveness of a medicine involves objective measures like clinical trial results and statistical analysis.

While even “objective” valuations can be influenced by factors like funding or research design, the goal is to minimize subjectivity and strive for a more widely accepted assessment of worth. Think of it like grading a test – there’s a rubric, a set of criteria, to determine the grade, even if there might be some wiggle room in interpretation.

The Role of Perspective in Valuation

Perspective, yo, it’s everything when it comes to figuring out what something’s worth. Your background, your experiences – they all color how you see things, and that directly impacts your valuation. It’s not just about the numbers, it’s about the story behind the numbers.

Personal Experiences Shaping Valuation

Personal experiences, like, seriously shape how we put a price tag on things. Think about it – your past totally influences your present judgments. Here’s the breakdown:

- Childhood Memory: Say, you grew up in a household where handmade items were highly valued. Maybe your grandma knitted you awesome sweaters. This could lead you to place a higher value on handcrafted goods compared to mass-produced items, maybe even a 20% premium because of the emotional connection and perceived craftsmanship.

- Significant Life Event: Let’s say you lost a valuable item in a theft. This traumatic experience might make you place a much higher value on security and insurance, impacting your valuation of similar possessions in the future, potentially increasing insurance coverage by 50% or more.

- Professional Training: If you’re an appraiser, your training teaches you to objectively assess value based on market trends and condition. This drastically reduces biases, creating valuations that differ significantly from someone without such training. For example, a trained appraiser might value a vintage car 10% higher than someone with no formal training due to their ability to recognize rarer features and market demand.

Now, let’s talk about those sneaky psychological biases that mess with our heads:

| Bias | Description | Impact on Valuation |

|---|---|---|

| Anchoring Bias | Sticking to the first number you hear, even if it’s totally bogus. | If someone initially offers a low price for a painting, you might undervalue it, even if it’s actually worth way more. |

| Availability Heuristic | Remembering things that are easy to recall, even if they’re not typical. | If you recently saw a news story about a rare coin selling for a fortune, you might overvalue any old coin you come across. |

| Confirmation Bias | Only paying attention to stuff that backs up your existing beliefs. | If you already think a certain brand is overpriced, you’ll only look for information confirming that belief, ignoring any evidence that suggests otherwise. |

Cultural Background’s Influence on Valuation

Culture, man, it’s a huge player. What’s precious in one culture might be totally worthless in another.Let’s compare the US and Japan:

- US (Individualistic Culture): Emphasis on personal achievement and materialism. A limited-edition sneaker might be valued highly for its status symbol, while a family heirloom might hold sentimental value but less monetary worth compared to its market value.

- Japan (Collectivist Culture): Emphasis on community and tradition. A family heirloom, like a centuries-old tea set, could hold immense value, far exceeding its market price, due to its historical and familial significance. A limited-edition sneaker might hold less value than in the US due to less focus on individualistic displays of wealth.

Cultural norms around gifts, inheritance, and markets also change things up: In some cultures, gifts are seen as symbolic gestures of relationship, not necessarily based on monetary value. Inheritance practices, too, heavily influence the valuation of family assets. Market transactions can be shaped by cultural beliefs about fairness and reciprocity.

Differing Perspectives on a Single Object

Let’s say we’ve got a beat-up old guitar.

- A music historian might value it at $500 because of its historical significance, recognizing it as a model used by a famous musician.

- A guitar collector might value it at $1500 because of its rarity and condition, focusing on its collectibility.

- A pawn shop owner might only value it at $100 based on its current condition and resale potential.

The differences stem from each individual’s unique experience and cultural perspective. The historian sees historical value, the collector sees market value, and the pawn shop owner sees immediate resale value.* The historian’s valuation is driven by their knowledge of music history and the guitar’s place within it.

- The collector’s valuation is influenced by their experience in the market for vintage instruments.

- The pawn shop owner’s valuation is based on their need to quickly resell the item at a profit.

These differing perspectives make market pricing and negotiation a complex dance. The final price will depend on who’s buying and selling, their needs, and the power dynamics at play.

In the somber landscape of Theory of Knowledge, the valuer is the quiet observer, the one who weighs perspectives with a heavy heart. They sift through the debris of knowledge, searching for meaning amidst the chaos, much like a student meticulously searching for words in a game of Educational Word Searches , seeking understanding in a world that often feels fragmented and uncertain.

Ultimately, the valuer in Theory of Knowledge finds solace not in the answers themselves, but in the poignant journey of the questions.

The Influence of Knowledge Systems on Valuation

Yo, let’s break down how different ways of knowing totally shape what we think is valuable. It’s not just about personal preference; the frameworks we use to understand the world—our knowledge systems—heavily influence our judgments of worth. Think about it: what’s “good” science isn’t always what’s “good” art, right?Different knowledge systems offer unique lenses through which we assess value.

The natural sciences, for example, emphasize objectivity, empirical evidence, and quantifiable results. In contrast, the arts prioritize subjective interpretation, emotional resonance, and creative expression. These differing approaches lead to vastly different valuation processes. The scientific method might value a drug based on its efficacy rate in clinical trials, while an art critic might value a painting based on its aesthetic impact and historical context.

This isn’t to say one is “better” than the other; they’re just different.

Biases Within Knowledge Systems and Their Impact on Valuation

Knowledge systems aren’t perfect; they’re created by humans, and humans are biased. These biases can seriously skew our valuations. For example, confirmation bias in the sciences might lead researchers to favor data supporting their pre-existing hypotheses, potentially overlooking contradictory evidence and inflating the perceived value of their findings. Similarly, in the arts, a prevailing aesthetic standard might overshadow the merit of works that deviate from established norms, leading to undervaluation of innovative or unconventional pieces.

Think about how long it took for Impressionism to gain widespread acceptance – its initial rejection demonstrates how entrenched biases can delay the recognition of value. Another example: a historian might unconsciously favor sources that align with their own political beliefs, shaping their assessment of a historical figure’s actions and impact. These biases aren’t always malicious; they’re often unconscious and deeply ingrained.

Comparing Valuation Processes in Natural Sciences and Arts

Let’s compare the valuation processes in two totally different knowledge areas: the natural sciences and the arts. In the natural sciences, valuation often involves a rigorous process of peer review, replication of studies, and statistical analysis. The value of a scientific discovery is often determined by its contribution to existing knowledge, its potential for practical application, and the strength of the evidence supporting it.

In the somber landscape of Theory of Knowledge, the valuer is the one who assigns meaning, a silent judge weighing perspectives. Consider the stark reality of accessing basic sustenance; the weight of needing assistance, perhaps even relying on programs like Food Stamps , highlights the subjective nature of value itself. Ultimately, the valuer, in this vast and often unforgiving world, remains the interpreter of these stark realities, shaping our understanding of what truly matters.

Think of a new medical treatment—its value is assessed based on clinical trials, long-term effects, and cost-effectiveness.In contrast, the valuation of art is much more subjective and context-dependent. While factors like the artist’s reputation, the historical significance of the work, and its technical skill can influence its value, the ultimate judgment often rests on individual interpretation and emotional response.

The price a painting fetches at auction is influenced by market forces, collector preferences, and the overall cultural climate, making it a less straightforward measure of inherent value compared to the more quantifiable metrics used in the sciences. The value of a piece of art can also increase over time based on its influence on subsequent artists or cultural shifts, unlike scientific discoveries which are either valid or invalid.

Valuation and Justification

Yo, so we’ve been talkin’ about how people put value on stuff in TOK, right? But it’s not just about

- what* they value, it’s about

- why*. Justifying your choices is a big part of the game, and it’s way more complex than you might think. This ain’t just about gut feelings; it’s about backing up your claims with solid reasoning.

Justifications for value judgments often rely on a mix of personal experiences, cultural norms, and established knowledge systems. Think about it: why doyou* value certain things? Is it because your family instilled those values in you? Did you learn them from your friends, your community, or your education? Or maybe it’s something you figured out on your own through personal experience.

Whatever it is, you’re building a case for your values, whether you realize it or not.

Criteria for Justifying Valuations

Different criteria are used to justify different valuations, depending on what’s being valued. Sometimes, it’s about practicality. For example, if you’re choosing a car, you might prioritize fuel efficiency, safety features, and reliability – all measurable and objective qualities. Other times, it’s about aesthetics. A painting’s value might be judged based on its composition, color palette, and emotional impact – criteria that are much more subjective.

Still other times, it’s about ethical considerations. Choosing to support a certain charity might be justified by its effectiveness, transparency, and alignment with your personal values.

Limitations of Justifying Subjective Valuations

Now, here’s where things get tricky. Subjective valuations, like judging the beauty of a sunset or the moral worth of an action, are notoriously hard to justify. There’s no single, universally accepted metric for measuring beauty or morality. What one person finds beautiful, another might find bland; what one person considers morally acceptable, another might find reprehensible.

Trying to impose a single, objective standard on these inherently subjective experiences often leads to clashes and disagreements. For example, one person might value a vintage record player because of its nostalgic value and craftsmanship, while another might see it as a clunky, outdated piece of technology. Both justifications are valid from their own perspectives, but they are difficult to compare objectively.

You can present your reasons, but ultimately, convincing someone else to share your subjective valuation is a challenge. It’s all about perspective, and sometimes, perspectives just don’t align, no matter how well-reasoned your argument might be.

The Valuer as a Knower

Yo, check it. We’ve been talking about valuation, right? But it’s not just some abstract concept; it’s deeply intertwined with how we, as knowers, actuallyget* knowledge. It’s all about the relationship between what we value and how we learn. Think of it as the ultimate filter for our knowledge intake.Valuation isn’t just a passive thing; it actively shapes what we choose to learn and how we understand it.

It’s like having a personal DJ for your brain, constantly curating the knowledge stream based on your preferences. This influence runs deep, affecting everything from what sources we trust to how we interpret data.

Valuation’s Impact on Knowledge Acquisition

Our values act as a compass, guiding our pursuit of knowledge. If you value environmental sustainability, you’ll probably seek out information about climate change and eco-friendly practices. Conversely, someone who values financial success might prioritize information on investment strategies and market trends. This targeted approach to knowledge acquisition means we actively seek out information that aligns with our values, reinforcing those beliefs and shaping our understanding of the world.

It’s a self-reinforcing cycle: we value certain things, so we seek out knowledge that supports those values, and that knowledge further strengthens our values.

Valuation’s Influence on Information Selection and Interpretation

Think about it: you’re researching a topic, let’s say the effectiveness of different teaching methods. If you strongly value a student-centered approach, you’re more likely to focus on studies that support that method and potentially downplay or even overlook research that contradicts it. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing – it’s a natural human tendency. However, recognizing this bias is crucial for critical thinking.

Understanding how our values influence what information we select and how we interpret it allows us to approach knowledge with a more balanced and nuanced perspective.

Valuation’s Contribution to Knowledge Growth

Now, this might seem counterintuitive, but our values actuallyfuel* the growth of knowledge. By focusing our attention on specific areas aligned with our values, we contribute to the accumulation of knowledge within those fields. For example, the strong values placed on human rights by many have led to extensive research and progress in areas like international law and social justice.

This concentrated effort driven by value systems creates specialized knowledge and drives innovation. It’s like a focused laser beam, burning through to new discoveries and insights.

Valuation and Ethical Considerations

Yo, let’s talk ethics in valuation. It’s not just about crunching numbers; it’s about making sure those numbers reflect reality and don’t get manipulated for personal gain. We’re diving into the ethical minefield of different valuation methods and how biases can totally skew the results. Think of it as keeping your valuation game legit.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Ethical Implications

DCF, the OG valuation method, relies heavily on future projections. The problem? Forecasting the future is, like, totally unpredictable. Ethical issues arise when assumptions about growth rates and discount rates are, let’s say,a little* too optimistic (or pessimistic) to suit a certain agenda. Manipulating these assumptions can paint a rosy picture (or a bleak one) that doesn’t reflect reality.

- Example 1: A company inflates projected growth rates to justify a higher valuation, securing a larger loan or attracting investors based on false promises of future performance. This is straight-up fraud, yo.

- Example 2: A company uses an unrealistically low discount rate to inflate the present value of future cash flows, making the company appear more valuable than it actually is. This is another way to cook the books, and it’s not cool.

Market Approach Ethical Implications

The market approach compares a company to similar ones that have been bought or sold. Sounds simple, right? But choosing comparable companies is where the ethical dilemmas pop up. Picking comparables that support a pre-determined valuation is, well, biased and shady.

- Example: A company intentionally selects only high-performing comparables to inflate its own valuation, ignoring less successful companies in the same industry. This is like cherry-picking data to get the result you want.

Asset Approach Ethical Implications

This method values a company based on its assets. Intangible assets (like brand reputation or intellectual property) and assets with uncertain future values (like undeveloped land) are tricky to value ethically. Misrepresenting the value of these assets can lead to major ethical issues.

- Example: A company overstates the value of its intellectual property to boost its overall valuation, potentially misleading potential buyers or investors. This is straight-up deception.

Identifying Potential Biases in Valuation

Bias is a real thing, and it can totally mess up your valuations. Here’s a breakdown of some common biases and how to avoid them:

| Bias Type | Description | Example | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmation Bias | Favoring information that confirms pre-existing beliefs. | Selecting comparable companies that support a predetermined valuation range. | Employing a diverse valuation team with varied perspectives. |

| Anchoring Bias | Over-reliance on the first piece of information received. | Giving excessive weight to an initial valuation estimate. | Using multiple independent valuation methods. |

| Availability Heuristic | Overestimating the likelihood of easily recalled events. | Overemphasizing recent market transactions while ignoring historical data. | Conducting thorough due diligence and considering a wide range of data. |

| Overconfidence Bias | Overestimating one’s own judgment and expertise. | Ignoring contradictory evidence or expert opinions. | Seeking external validation and peer review. |

| Halo Effect | Letting positive impressions influence overall judgment. | Overvaluing a company based on its strong brand reputation alone. | Focusing on objective financial data and avoiding emotional biases. |

Enron Scandal: A Case Study in Ethical Failures

The Enron scandal is, like, the ultimate example of how ethical failures can crash a company. Enron used special purpose entities (SPEs), which are basically off-the-books companies, to hide debt and inflate earnings. This created a false picture of Enron’s financial health, leading to an artificially high valuation. Investors were misled, and when the truth came out, the whole thing imploded.

The ethical failures involved included accounting fraud, conflicts of interest, and a lack of transparency. The consequences were devastating – job losses, investor losses, and a major shake-up in accounting regulations. This whole situation shows how crucial ethical considerations are in valuation. It’s not just about the numbers; it’s about integrity.

The Impact of Emotion on Valuation

Yo, let’s be real: our feelings totally mess with how we judge things. It’s not always a bad thing, but understanding how emotions skew our valuations is key to becoming a sharper thinker. We’re talking about how our gut reactions and emotional responses shape what we deem valuable, from a vintage sneaker to a political candidate.Emotions influence the valuation process by acting as powerful filters through which we process information.

Think of it like this: your brain’s got two main systems running – the logical, reasoning part, and the emotional, feeling part. They’re constantly chatting, but sometimes one shouts louder than the other. When strong emotions are involved, they can override rational analysis, leading to valuations that might not align with objective criteria. Fear, excitement, anger – these all color our perceptions and dramatically impact what we consider valuable or worthwhile.

Examples of Emotionally Biased Valuations

Okay, so let’s break down some real-world examples where emotions totally hijacked the valuation process. Imagine you’re a huge fan of a particular artist. You’re at an auction, and a rare piece of their artwork is up for grabs. You might be so emotionally invested that you’re willing to pay way over the market price, driven by your passion and desire to own a piece of your idol’s legacy.

That’s an emotional valuation, possibly inaccurate compared to a purely market-driven assessment. Another example: think about the housing market. During a housing boom, driven by fear of missing out (FOMO), people often overvalue properties, leading to inflated prices and eventually a market crash. The intense emotion of FOMO trumps rational analysis of market trends and potential risks.

Reason and Emotion in Valuation: A Tug-of-War

The relationship between reason and emotion in valuation is best described as a constant tug-of-war. Ideally, we strive for a balanced approach, where reason guides our assessments while acknowledging the influence of emotions. Reason helps us analyze data, weigh pros and cons, and make objective judgments. Emotion adds a layer of subjective experience, personal preference, and sometimes, irrationality.

The challenge lies in recognizing when emotions are clouding our judgment and actively working to mitigate their influence. It’s not about eliminating emotions entirely – that’s impossible – but about developing the self-awareness to identify and manage their impact on our valuations. Think of it like learning to surf: you need the power of the wave (emotion) but also the skill to ride it (reason) without getting wiped out.

Valuation and Power Dynamics: Who Is A Valuer In Theory Of Knowledge

Yo, let’s dive into how power trips affect how we put a price tag on things. It’s not just about the numbers; it’s about who holds the cards and how that shapes the whole game. We’re talking about how socioeconomic status, gender, and race mess with the valuation process, from real estate to corporate takeovers.

Power Structures and Valuation Judgments

Power structures, like the invisible hand guiding the market, subtly (or not so subtly) skew valuation judgments. Think about real estate appraisal: a historically marginalized community might see their property consistently undervalued compared to similar properties in wealthier neighborhoods. This isn’t just about market forces; it’s about ingrained biases reflecting existing power imbalances. For example, studies have shown that properties in predominantly Black neighborhoods are often appraised for less than comparable properties in white neighborhoods, even when controlling for objective factors like size and location.

This disparity directly translates to less wealth accumulation for these communities. Negotiations are also affected. A wealthy developer negotiating with a low-income homeowner has a clear power advantage, leading to potentially unfair deals. Different valuation methodologies can either perpetuate or try to counteract these biases. For instance, using comparative market analysis (CMA) without carefully addressing historical biases can reinforce existing inequalities, while incorporating adjustments for historical discrimination in the appraisal process can aim for a fairer valuation.

Dominant Narratives and Valuation

The stories we tell ourselves—the dominant narratives—shape how we see value. Think about ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing. Companies seen as environmentally friendly or socially responsible often command higher valuations, reflecting investor preferences shaped by narratives around sustainability and ethical business practices. Conversely, companies facing negative media coverage related to environmental damage or labor practices can see their stock prices plummet.

Media plays a huge role here. A scathing exposé on a company’s unethical practices can significantly influence public opinion and, consequently, investor sentiment and valuation. The narrative becomes reality in the market.

| Asset Class | Dominant Narrative | Valuation Metric | Narrative Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Estate | Sustainable Development | Price per square foot | Higher valuation for green buildings, lower for those in environmentally challenged areas |

| Stocks | Technological Innovation | Price-to-earnings ratio | Higher valuations for tech companies perceived as innovative, lower for those seen as lagging |

| Art | Social Responsibility | Auction price | Higher valuations for art from artists with strong social messages, lower for those perceived as lacking social relevance |

Scenario: Power’s Influence on Valuation

Imagine a large corporation wanting to build a new factory on land owned by a small farming community. The corporation, wielding significant financial and political power, employs sophisticated valuation methods that downplay the community’s long-term economic reliance on the land, valuing it primarily for its raw industrial potential. The community, lacking resources for expert valuation, struggles to counter this assessment.

The corporation’s valuation heavily favors its own interests, ultimately leading to a land acquisition at a price far below the community’s perceived value. This scenario highlights the ethical issues inherent in unequal power dynamics. A more equitable scenario might involve government mediation, independent appraisals, or community-based land trusts, ensuring the community’s voice is heard and their interests protected.

Further Analysis (Qualitative Data)

Power dynamics aren’t just about the bottom line; they affecthow* we see value. The corporation in our scenario might see the land solely as a resource for profit, while the farming community sees it as their livelihood, their history, their identity – values that are hard to quantify but incredibly significant. This difference in perception stems directly from their vastly different positions within the power structure.

The community’s perceived value is intrinsically linked to their cultural and historical attachment to the land, a factor largely ignored by the corporation’s purely financial valuation.

Further Analysis (Quantitative Data)

| Metric | Scenario A (Unequal Power) | Scenario B (Equal Power) | Difference/Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Valuation | $1 million (Corp) / $5 million (Community) | $3 million (Both) | Significant initial disparity reflects power imbalance; equal power leads to a more agreeable starting point. |

| Final Valuation | $1.2 million | $3.5 million | Final valuation in Scenario A significantly undervalues the land; Scenario B shows a more equitable outcome. |

| Negotiation Time | Short, abrupt | Lengthy, collaborative | Unequal power leads to a quick, unfair settlement; equal power requires more time for negotiation. |

| Outcome Fairness | Highly unfair to community | Fair to both parties | The unequal power dynamic results in an unfair outcome, while equal power leads to a fairer result. |

Valuation in Different Contexts

Yo, let’s break down how we value things in different areas of life – it’s way more complex than just slapping a price tag on something. We’re talking science, art, and morals, and how our perspectives totally shape what we consider valuable.Valuation isn’t some one-size-fits-all deal; it’s all about the context. What’s prized in a lab might be totally irrelevant in an art gallery, and what’s considered morally upright in one culture might be a total no-no in another.

We’re gonna dive into how these different fields approach valuation and the unique challenges they face.

Scientific Valuation

Science, right? All about facts, data, and objective truth. But even in science, valuation plays a huge role. We value certain research methods over others based on their reliability and validity. We value theories based on the strength of their evidence and their ability to explain phenomena.

Funding decisions in scientific research are also based on valuations of potential societal benefit and scientific advancement. Think about it: a groundbreaking discovery in cancer research is valued far higher than a study on the mating habits of dung beetles (no disrespect to dung beetles!). The challenges here lie in balancing objective data with subjective judgments about what constitutes significant progress or societal impact.

For example, determining the value of basic research, which may not have immediate applications, is a constant struggle. Funding agencies often favor projects with clear, short-term benefits, potentially neglecting crucial areas of fundamental research that could lead to future breakthroughs.

Artistic Valuation

Art’s a whole different ball game. It’s subjective, emotional, and deeply personal. What one person considers a masterpiece, another might see as a pile of junk. Artistic valuation often involves considering factors like originality, skill, aesthetic appeal, cultural significance, and historical context. The market value of a piece of art can fluctuate wildly based on trends, artist reputation, and even simple supply and demand.

Think about the crazy prices fetched by famous paintings – it’s not always about the inherent “quality” but also about the cultural capital and social status associated with owning such a piece. The challenge here is the lack of objective standards. There’s no single metric to measure the “value” of a work of art; it’s a complex interplay of various factors, often influenced by speculation and social trends.

Moral Valuation

Moral valuation is about judging the rightness or wrongness of actions, policies, or character traits. This is where things get REALLY tricky, because it often depends on deeply held beliefs, cultural norms, and personal experiences. We value things like honesty, compassion, justice, and fairness, but the specific application of these values can vary widely. Consider the debate around capital punishment or abortion – the valuations are deeply personal and often lead to fierce disagreements.

The challenge in moral valuation is that there’s often no universally agreed-upon standard for determining what is “good” or “bad.” Different ethical frameworks (utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics) offer different perspectives and approaches, making it difficult to reach consensus. The influence of cultural background, religious beliefs, and personal experiences further complicates the process.

The Evolution of Valuation

Valuation, yo, it ain’t static. It’s a constantly evolving game, shaped by market shifts, tech advancements, and changes in how we think about money. This ain’t just some dusty textbook stuff; it’s the real-world pulse of finance. Understanding its evolution is key to navigating the financial landscape.

Specific Valuation Methods: A Historical Perspective

Different valuation methods have risen and fallen in popularity over the years. Understanding their strengths and weaknesses across time gives us a clearer picture of how valuation has adapted. Think of it like comparing old-school boomboxes to today’s wireless earbuds – both play music, but the tech and experience are worlds apart.

| Valuation Method | 1970s-1980s | 1990s-2000s | 2010s-Present |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) | Limited use, complex calculations | Increased adoption, improved software | Widely used, refined terminal value methods, incorporating more sophisticated risk assessments. |

| Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) | Primarily relied on industry averages | More sophisticated peer group selection, broader data access | Emphasis on comparable metrics, adjustments for company-specific factors, use of statistical analysis |

| Precedent Transactions | Limited data availability, reliance on anecdotal evidence | Databases emerge, increased transaction data | Robust databases, sophisticated control variables in analysis, increased use in private company valuations |

Market Influences on Valuation Methodologies

Macroeconomic factors, like interest rates and inflation, massively influence how we value things. Think of it like this: high interest rates make future cash flows less valuable today, impacting DCF calculations.

- 1970s-1980s: High inflation and interest rates led to a focus on shorter-term valuation horizons and higher discount rates.

- 1990s-2000s: Lower interest rates and increased economic growth fueled higher valuation multiples and a boom in tech valuations (dot-com bubble!).

- 2010s-Present: Periods of low interest rates, followed by recent increases, have created volatility in valuation multiples and increased the importance of risk assessment.

Technological Impacts on Valuation

Tech has revolutionized valuation, making it faster, more accurate, and accessible. High-frequency trading, for instance, allows for incredibly rapid price adjustments, affecting valuation in real-time. Real-time data streams provide up-to-the-second insights, enhancing the accuracy of valuations.

Industry Disruption and Valuation Shifts

Think about the impact of Netflix on Blockbuster. Disruptive technologies can completely reshape industries, sending valuations skyrocketing for some and plummeting for others. The rise of streaming services decimated Blockbuster’s valuation, while Netflix’s soared.

Regulatory Changes and Valuation Practices

Regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) and Dodd-Frank have significantly impacted valuation practices, especially regarding transparency and corporate governance. SOX, for example, increased the scrutiny of financial reporting, impacting valuation inputs and methodologies.

Accounting Standards and Valuation Methodologies

Changes in accounting standards (GAAP, IFRS) directly affect how companies report financial data, impacting valuation inputs and calculations. Differences in accounting standards between countries can also lead to variations in valuations.

Investor Sentiment and Valuation Fluctuations

Investor sentiment, whether optimistic or pessimistic, drives market fluctuations and significantly impacts valuations. Market bubbles, like the dot-com bubble, are prime examples of how extreme optimism can inflate valuations beyond their intrinsic worth. Conversely, market crashes demonstrate how pessimism can lead to sharp declines.

Historical Examples of Evolving Valuations

Apple’s Valuation Over Time

Apple’s valuation has seen massive swings over the past two decades. Early 2000s, it was a struggling company. Then, the iPhone revolutionized the market, leading to exponential growth in its valuation. A line graph would show a dramatic upward trend, with fluctuations reflecting market sentiment and product releases.

In the somber landscape of Theory of Knowledge, the valuer is the one who grapples with the weight of perspectives, assigning significance to beliefs and experiences. Their journey, a quiet contemplation of truth’s elusive nature, echoes the profound message of Choose Life Choose Words , a call to conscious expression. Ultimately, the valuer, in their quiet assessment, shapes the narrative of knowledge, a solitary figure amidst the echoes of unspoken truths.

The Dot-Com Bubble

The dot-com bubble serves as a cautionary tale of how irrational exuberance can lead to unsustainable valuations. Many internet companies were valued based on potential rather than current profitability, resulting in a spectacular collapse. The key lesson is the importance of fundamental analysis and realistic expectations.

Comparative Analysis: Coca-Cola vs. PepsiCo

A table comparing Coca-Cola and PepsiCo’s valuations over the past 20 years would highlight similarities and differences, driven by factors like brand loyalty, marketing strategies, and overall market performance. Similar industry but different trajectories.

Data Requirements, Who is a valuer in theory of knowledge

Reliable valuation analysis requires data from various sources: financial databases (Bloomberg, Refinitiv), company filings (10-Ks, annual reports), and industry reports.

The Limitations of Valuation

Yo, let’s get real about valuation. It ain’t always as straightforward as it seems. There are serious limitations to how accurately we can put a price tag on things, especially when dealing with complex assets like businesses or real estate. This ain’t just about numbers; it’s about understanding the inherent flaws in the process.

Limitations in Real Estate Valuation

| Limitation | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Data Scarcity | Limited comparable sales data, especially for unique properties, makes accurate market analysis difficult. | Trying to value a historic mansion in a rural area with few recent comparable sales. Appraisers might have to rely on less relevant data, leading to a wider margin of error. |

| Subjectivity in Adjustments | Adjustments for differences between comparable properties (size, location, condition) involve judgment calls that can significantly impact the final valuation. | Two appraisers might disagree on the appropriate adjustment for a property’s outdated kitchen, leading to different valuations even when using the same comparable properties. |

| Unforeseen Market Shifts | Rapid changes in interest rates, economic conditions, or local market trends can quickly render a valuation obsolete. | A property valued at $500,000 during a housing boom might be worth significantly less just months later if interest rates spike and the market cools down. |

Subjective Biases in Valuation

Three major factors contribute to subjective biases: Confirmation bias, where appraisers unconsciously favor information confirming their initial assumptions; anchoring bias, where the initial valuation heavily influences subsequent adjustments; and availability bias, where readily available information (like recent comparable sales) disproportionately influences the valuation, even if it isn’t entirely representative.For example, confirmation bias might lead an appraiser who initially believes a property is undervalued to selectively focus on positive features and overlook negative ones. Anchoring bias might cause an appraiser to start with a high initial estimate and make insufficient downward adjustments even after discovering negative aspects. Availability bias might lead an appraiser to overemphasize recent high-value sales while neglecting slower market trends.

Comparing Valuation Methodologies

Let’s compare the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) and Market Comparable approaches. DCF projects future cash flows and discounts them back to present value. Market Comparable analyzes similar assets’ recent sales. Both are subjective.DCF’s subjectivity lies in predicting future cash flows and choosing the discount rate. For instance, let’s say a company projects $10 million in annual cash flow for the next five years.

Using a 10% discount rate yields a valuation of $37.9 million. But a 12% discount rate yields only $31.7 million – a significant difference based solely on the discount rate assumption.Market Comparable relies on the comparability of assets, which is often debatable. If three comparable companies sold for $20 million, $25 million, and $30 million, the average is $25 million.

But if one company had superior technology or management, that average might be misleading.

Mitigation Strategies for Subjectivity

To reduce subjectivity, use multiple valuation methods, thoroughly document assumptions, employ sensitivity analysis (testing different assumptions), and involve independent experts to review the valuation. Peer review is crucial.

Impact of Market Conditions

Volatile market conditions significantly impact valuation reliability.

- High Inflation: Erodes the purchasing power of future cash flows, making DCF valuations lower.

- Recession: Reduces market demand and asset values, affecting both DCF and Market Comparable approaches.

- Rapid Growth: Can inflate asset values beyond their intrinsic worth, leading to overvaluation.

Information Asymmetry

Incomplete or unavailable information creates valuation discrepancies. Buyers might undervalue a property due to hidden defects unknown to them, while sellers might overvalue it due to their emotional attachment. Investors facing information asymmetry might overpay for assets they perceive as having higher growth potential than is actually warranted.

Future Uncertainties

Predicting future cash flows, growth, and discount rates is challenging. A small change in these assumptions can dramatically alter valuations. Consider a company projecting $10 million in annual cash flows for five years. A sensitivity analysis showing the valuation range with discount rates varying from 8% to 12% would highlight the significant impact of this uncertainty.

| Discount Rate | Valuation |

|---|---|

| 8% | $46.6 million |

| 10% | $37.9 million |

| 12% | $31.7 million |

Comparing Valuation Approaches’ Susceptibility to Bias

- Market Comparable: Highly susceptible due to reliance on subjective comparability judgments and the influence of recent market trends.

- Discounted Cash Flow: Moderately susceptible due to the subjective nature of forecasting future cash flows and selecting discount rates.

- Asset-Based Valuation: Less susceptible as it focuses on the net asset value, but still prone to biases in estimating asset values and liabilities.

The Interconnectedness of Valuations

Yo, let’s break down how different valuation methods totally vibe with each other – sometimes harmoniously, sometimes like a total clash of the titans. We’re talking about the interconnectedness of valuations, where one method’s results can seriously impact another, leading to some serious head-scratching moments.

Valuation Method Interactions

Different valuation methods, like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Comparable Company Analysis (CCA), and Precedent Transactions (PT), aren’t isolated islands. They’re all connected, influencing each other’s assumptions and conclusions. For example, a high valuation from a DCF analysis might lead you to expect higher multiples in a CCA, while low precedent transaction multiples could cast doubt on optimistic DCF projections.

Inconsistencies can arise when, say, a DCF suggests a much higher value than CCA or PT, forcing you to re-examine assumptions in each method. This might involve adjusting discount rates, growth rates, or even the selection of comparable companies. Circular reasoning is a real risk; you could end up using a CCA to justify a DCF assumption, which then supports the CCA’s outcome—a total feedback loop.

Factors Influencing Interconnected Valuations

The market’s mood swings, the economy’s ups and downs (interest rates, inflation, growth), and industry-specific trends all play a huge role in how valuations connect. Market sentiment, for instance, can inflate multiples across the board, regardless of individual company fundamentals. High interest rates can crush DCF valuations by increasing the discount rate, while inflation can mess with projected cash flows.

Industry trends can affect comparable companies, throwing off CCA multiples.

| Valuation Method | Interest Rate Changes | Inflation | Industry Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) | High sensitivity (discount rate) | High sensitivity (cash flow projections) | High sensitivity (growth rate) |

| Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) | Moderate sensitivity (market multiples) | Moderate sensitivity (earnings & revenue) | High sensitivity (growth comparisons) |

| Precedent Transactions (PT) | Low sensitivity (past transactions) | Low sensitivity (past transactions) | Moderate sensitivity (transaction context) |

A Simplified Valuation Model

Let’s say we’re valuing a tech startup, “CodeCrusaders.” We’ll use a simplified model:* DCF: Assume a revenue growth rate (g) of 20%, a discount rate (r) of 10%, and terminal growth rate of 3%. Let’s say our projected future cash flows add up to $100 million in present value.* CCA: Assume similar tech companies trade at an average Price-to-Sales (P/S) multiple of 5x.

In the somber landscape of Theory of Knowledge, the valuer is a ghost, a silent observer weighing the significance of claims. They grapple with the weight of understanding, seeking to build a framework of meaning, a process often mirroring the struggle to absorb knowledge base and synthesize disparate facts. Ultimately, the valuer remains a solitary figure, forever questioning the very foundations of their own judgments, a melancholic pursuit of truth.

If CodeCrusaders’ projected revenue is $20 million, the implied valuation is $100 million (20m – 5x).* PT: Let’s say recent acquisitions in the same sector show an average multiple of 4x sales. Using the same $20 million revenue projection, the implied valuation is $80 million.Now, let’s change the revenue growth assumption in the DCF to 15%. This decrease would lower the DCF valuation, likely causing a downward adjustment in the implied multiples used in CCA, reflecting a less optimistic outlook.

The PT valuation might remain relatively stable, as it’s based on past transactions.

Data Quality’s Impact

Garbage in, garbage out. Inaccurate or inconsistent data across valuation methods will spread like wildfire, leading to unreliable conclusions. For example, using flawed revenue projections in the DCF will directly affect CCA and PT, leading to mismatched valuations. Inconsistent accounting practices across comparable companies can skew CCA results.

Expert Judgment’s Role

Experienced valuers use their skills to reconcile discrepancies. They consider qualitative factors like management quality, competitive landscape, and regulatory changes. These factors might justify a higher valuation despite lower quantitative results. They also know when to rely more on one method over others, given data limitations.

Industry-Specific Applications

In the tech industry, DCF and CCA are often heavily used due to the focus on future growth and comparable companies. In real estate, PT and income capitalization methods (similar to DCF but focused on rental income) are more prominent, reflecting the asset-heavy nature of the industry. The relative importance of different methods varies based on data availability and industry characteristics.

The Practical Application of Valuation Theory

Valuation theory, while sounding super academic, is actually super practical and pops up everywhere in the real world. It’s all about figuring out what something is worth, not just in dollars and cents, but in terms of its impact, its meaning, and its overall significance. From personal decisions to global policy, understanding how we value things shapes our choices and actions.It’s not just about money, yo.

In the somber landscape of Theory of Knowledge, the valuer is a ghost, a silent judge of the ephemeral. They weigh the worth of knowledge, a task as heavy as the heart. To understand their elusive role, consider the vast, structured repository of information found within the citect knowledge base , a testament to human endeavor, yet only a fraction of what the valuer must consider.

Ultimately, the valuer remains a solitary figure, ever questioning the fleeting nature of truth itself.

Valuation theory helps us make sense of everything from choosing a college to deciding on a career path, to understanding global conflicts. It’s about weighing options, considering perspectives, and ultimately making informed choices based on our own unique set of values.

Valuation in Business and Finance

In the business world, valuation is key. Companies use valuation techniques to determine the worth of assets, investments, and even entire businesses. For example, when a company goes public through an Initial Public Offering (IPO), investment banks use complex models to estimate the company’s value, influencing the price at which shares are offered. These models consider factors like projected earnings, market conditions, and the company’s competitive landscape.

Another example is mergers and acquisitions, where companies need to determine the fair market value of a target company before making an offer. Incorrect valuation can lead to overpaying or missing out on lucrative opportunities. Different valuation methods exist, such as discounted cash flow analysis and comparable company analysis, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Valuation in Environmental Policy

Environmental policy relies heavily on valuation. How do we put a price on a pristine rainforest or a clean river? This isn’t always about monetary value, but about weighing the ecological, social, and economic benefits of preserving these resources against the costs of development or exploitation. Cost-benefit analysis is a common tool used in environmental decision-making, attempting to quantify the positive and negative impacts of a project or policy.

For instance, a proposed dam project might be assessed based on the economic benefits of hydroelectric power versus the ecological costs of habitat destruction and loss of biodiversity. These valuations often involve subjective judgments and different stakeholders may have vastly different perspectives.

Applying Valuation Theory: A Case Study – Choosing a College

Let’s say you’re facing the epic decision of choosing a college. Applying valuation theory means considering various factors beyond just prestige or rankings. You might create a weighted scoring system. Assign weights to factors like academic program quality (e.g., 40%), cost and financial aid (e.g., 25%), location and campus environment (e.g., 20%), and career prospects (e.g., 15%).

Then, score each college on a scale for each factor. Multiply the score by the weight and sum the results for each college. This method allows for a more systematic and objective approach to comparing different options, making the overwhelming college application process a little more manageable. The weights themselves reflect your personal values and priorities.

The Future of Valuation

Yo, what’s up, future valuers! The game’s changing faster than a TikTok trend, and how we put a price tag on things is about to get a serious upgrade. We’re talking about the future of valuation, a field poised for a major disruption thanks to tech, shifting social priorities, and some seriously unpredictable global events. Buckle up, it’s gonna be wild.

Speculative Trends in Valuation Theory

The landscape of valuation is getting a total makeover. New data, AI, and evolving social concerns are reshaping how we determine value, leading to some seriously interesting (and potentially lucrative) shifts.

Impact of ESG Factors

ESG – that’s Environmental, Social, and Governance – is no longer a niche concern; it’s mainstream. Companies that aren’t playing ball with sustainability and ethical practices are facing major heat, and that’s impacting their valuations. Over the next decade, we’ll see a massive shift. Companies with strong ESG profiles will see their valuations boosted, while those lagging behind will take a hit.

| Sector | Current Valuation Method | Projected ESG Adjustment (2033) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | Discounted Cash Flow | -15% | The energy sector is facing increasing pressure to transition to renewable energy sources. Companies heavily reliant on fossil fuels will likely see a decrease in valuation as investors prioritize sustainable alternatives. This is based on current trends showing decreasing demand for fossil fuels and increasing regulations. |

| Technology | Multiples | +10% | Tech companies with strong data privacy practices and commitment to ethical AI development will be rewarded. Investors are increasingly prioritizing companies with responsible data handling and ethical business practices. This is based on the growing demand for responsible tech and increased scrutiny of data privacy. |

| Consumer Goods | Asset-Based Valuation | +5% | Companies focusing on sustainable sourcing, ethical labor practices, and reducing their carbon footprint will attract more investment. Consumers are increasingly demanding ethical and sustainable products. This is based on the growing consumer preference for sustainable and ethically sourced goods. |

Alternative Data Sources

Forget relying solely on traditional financial statements. The future of valuation is all about alternative data. Think social media sentiment analyzing public opinion on a brand, satellite imagery assessing the condition of real estate, or transactional data revealing real-time market dynamics. Integrating these sources will give us a much more nuanced and accurate picture of value. However, we’ll need to develop robust methods for validating and interpreting this data to avoid biases and inaccuracies.

For example, analyzing social media sentiment requires sophisticated natural language processing to avoid misinterpretations.

Rise of AI in Valuation

AI is about to become the valuation MVP. It can automate tasks like data cleaning, model building, and even risk assessment. This frees up human valuers to focus on more complex tasks like strategy and interpretation. However, we need to be mindful of potential biases in AI algorithms and ensure transparency in how these tools are used.

For instance, if an AI model is trained on historical data that reflects existing biases, it may perpetuate those biases in its valuations.

Technological Impact on Valuation

Technology is not just enhancing valuation; it’s revolutionizing it. New tools are changing the game in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Blockchain Technology

Blockchain is bringing unprecedented transparency and security to asset tracking and verification. Imagine tracking the ownership and provenance of luxury goods, verifying the authenticity of digital assets, or streamlining real estate transactions with immutable records. This will significantly impact the valuation of these assets, leading to more accurate and efficient processes. For example, in the art market, blockchain can help authenticate artworks and prevent fraud, thereby impacting their valuation.

Big Data Analytics

Big data is the key to unlocking more accurate and efficient valuation models. By analyzing massive datasets, we can identify hidden patterns, predict market trends, and mitigate risks more effectively. For example, analyzing consumer spending patterns can help valuers predict the future demand for certain products, impacting their valuation.

Hypothetical Future Challenges in Valuation

Let’s paint a picture of the future. It’s 2035, and a major climate-related event has upended global markets. Traditional valuation methods are struggling to keep up.

Scenario Development

A catastrophic solar flare has knocked out global power grids for months, causing widespread economic disruption. The valuations of energy companies and technology firms reliant on complex digital infrastructure are in freefall. Real estate values in coastal areas are plummeting due to rising sea levels, while assets in more resilient inland areas are seeing increased demand.

Solutions and Adaptations

Solution 1

Develop new valuation models that incorporate climate-related risks and resilience factors. This requires integrating climate science data into financial models to assess the long-term impact on assets.

Solution 2

Create a global standard for assessing the resilience of infrastructure and assets to extreme weather events. This would require international collaboration to establish common metrics and methodologies.

Solution 3

Implement robust stress testing methodologies to assess the vulnerability of different asset classes to future shocks. This would require developing scenarios that consider a wider range of potential future events and their impacts.

Ethical Considerations

As we rely more on AI, big data, and alternative data sources, ethical considerations become paramount. We need to ensure transparency, avoid biases, and hold ourselves accountable for the valuations we produce. The use of AI in valuation requires careful consideration of potential biases and the need for human oversight to ensure fairness and accuracy.

Popular Questions

What’s the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic value?

Intrinsic value is inherent to an object itself (like a precious gem’s beauty), while extrinsic value comes from external factors (like a painting’s high price due to artist fame).

Can a valuer be completely objective?

Nope! Even scientists striving for objectivity bring biases and assumptions to their work. Complete objectivity is the holy grail of valuation – a pretty elusive one.

How does emotion affect valuation?

Emotions can wildly distort our judgments. Think of that “gotta have it now!” feeling – suddenly, that overpriced novelty item seems essential!

What are some common valuation pitfalls to avoid?

Overconfidence, anchoring bias (sticking to initial impressions), and confirmation bias (seeking only supporting evidence) are major culprits.