When was miasma theory made? The question itself unravels a fascinating chapter in the history of medicine, a time when the stench of decay, the miasma, was believed to be the harbinger of disease. Long before the germ theory revolutionized our understanding of illness, a miasmatic cloud hung heavy over medical thought, shaping public health practices, and influencing the very fabric of societal life.

This exploration delves into the murky origins of this theory, tracing its rise to prominence, its eventual decline, and its surprisingly enduring legacy in our modern world.

From ancient civilizations hinting at the dangers of “bad air” to the meticulous observations of 18th and 19th-century physicians, the miasma theory held sway for centuries. We’ll examine the key figures who championed this theory, the publications that solidified its acceptance, and the societal factors that fueled its belief. We’ll unearth the scientific advancements and limitations of the era that shaped its acceptance, and the cultural anxieties that made it so compelling.

This journey will not only reveal the “when” but also the “why” and “how” of this pivotal theory, revealing a complex interplay of science, society, and the enduring human quest to understand disease.

Early Mentions of Miasma: When Was Miasma Theory Made

The concept of disease arising from foul air, though formalized later as miasma theory, has ancient roots, appearing in various cultures and across millennia. These early mentions, while not forming a cohesive scientific theory, reveal a consistent understanding of a link between environmental conditions and illness, shaping societal responses to disease outbreaks. Examining these historical instances provides crucial context for understanding the eventual development and widespread acceptance of the miasma theory itself.The understanding of disease causation was deeply intertwined with prevailing philosophical and religious beliefs.

Early civilizations often attributed illness to supernatural forces or imbalances in the natural world, and the concept of “bad air” often served as a bridge between these spiritual explanations and observable phenomena. The perceived link between foul smells and sickness wasn’t necessarily a scientific hypothesis, but rather a pragmatic observation that informed practices aimed at preventing disease. This practical application, despite its lack of scientific rigor, is significant in understanding the societal influence of these early miasma-like ideas.

Ancient Greek and Roman Understandings of Miasma

Ancient Greek physicians, notably Hippocrates, described the influence of environmental factors on health. While not explicitly formulating a “miasma theory,” Hippocrates emphasized the importance of air, water, and climate in maintaining health and causing disease. His treatise “Airs, Waters, Places” details the impact of geographical location and environmental conditions on the prevalence of various illnesses. This work highlights the recognition of a correlation between environmental factors and disease, although the underlying mechanisms remained unclear.

Similarly, Roman writers such as Pliny the Elder also described the negative effects of “foul air” and emphasized sanitation practices to mitigate the spread of disease. These early writings reflect a growing awareness of the connection between environmental conditions and public health, laying the groundwork for later developments in the understanding of disease transmission. The difference between these early observations and the later formalized miasma theory lies primarily in the absence of a structured, scientifically testable hypothesis.

The ancients observed correlations but lacked the tools and methodologies to investigate the underlying causes.

Early Chinese Perspectives on Miasma

In ancient China, the concept of “qi” (氣), often translated as vital energy or life force, played a crucial role in understanding health and disease. Imbalances in qi, often associated with polluted or stagnant air, were believed to contribute to illness. Traditional Chinese medicine incorporated practices aimed at maintaining a balance of qi, including techniques to purify the air and promote proper ventilation.

While the concept of qi differs significantly from the later Western miasma theory in its philosophical underpinnings, it shares the common element of associating ill health with environmental factors, particularly the quality of the air. The focus on air quality and its influence on health is a clear parallel between these two distinct cultural approaches to understanding disease. However, the methods of explaining and addressing these concerns were markedly different, reflecting the unique philosophical and medical traditions of each culture.

Key Contributors and Their Roles

The miasma theory, while ultimately superseded, held significant sway over public health practices for centuries. Understanding its development requires examining the contributions of key figures whose research, publications, and observations shaped its acceptance and eventual decline. Their work, situated within the scientific and social context of their time, offers valuable insights into the evolution of medical thought.

Key Contributors and Their Contributions

| Name | Nationality | Publication(s) | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocrates | Greek | Airs, Waters, Places (c. 400 BC) | Early observations linking environmental factors, particularly air quality, to disease. He emphasized the importance of location and climate in influencing health. |

| Girolamo Fracastoro | Italian | De Contagionibus et Contagiosis Morbis (1546) | Proposed a theory of contagion, suggesting that disease could be transmitted through direct contact, indirect contact with contaminated objects, or through the air over short distances. This challenged the purely miasmatic view, though it wasn’t widely accepted at the time. |

| John Snow | British | On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1855) | His meticulous epidemiological work during the Broad Street cholera outbreak provided evidence against the miasma theory, demonstrating the role of contaminated water as a source of disease transmission. |

Individual Contributor Analysis

Hippocrates, a prominent figure in ancient Greek medicine, laid some of the groundwork for the miasma theory in his treatise Airs, Waters, Places. Born around 460 BC and considered the “Father of Medicine,” his observations linked environmental factors like air quality, water sources, and climate to the prevalence of disease. While lacking the germ theory’s understanding of microorganisms, his emphasis on environmental influences contributed to the development of the miasma concept, which would gain prominence centuries later.

His work’s lasting legacy lies in its influence on medical thinking, highlighting the importance of context in understanding health and disease.

Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553), an Italian physician and poet, offered a significant challenge to the purely miasmatic view with his publication De Contagionibus et Contagiosis Morbis in

1546. His work proposed a theory of contagion that included three modes of transmission: direct contact, indirect contact, and fomites (contaminated objects). He even suggested the possibility of airborne transmission, albeit over short distances. This marked a shift away from solely attributing disease to foul air, though his ideas were not widely adopted until much later.

His work highlights the gradual evolution of understanding regarding disease transmission and the limitations of solely relying on environmental explanations.

John Snow (1813-1858), a British physician and anesthesiologist, played a pivotal role in challenging the miasma theory. His investigation into the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak in London is a landmark study in epidemiology. Through meticulous mapping and data analysis, Snow demonstrated a strong correlation between cholera cases and a specific water pump on Broad Street. This provided compelling evidence against the prevailing miasma theory, suggesting that contaminated water, not foul air, was the primary source of the epidemic.

His work represents a critical turning point in understanding disease transmission and paved the way for the germ theory. Snow’s legacy remains firmly established as a pioneer of epidemiological methods and a crucial figure in the shift away from miasma.

Interactive Timeline (Placeholder – Requires JavaScript implementation)

An interactive timeline would be included here, displaying key dates and events related to the miasma theory, including publications, major outbreaks, and significant challenges to the theory. This would utilize HTML, CSS, and JavaScript (or a suitable library) for dynamic presentation. (Implementation omitted due to limitations of this text-based response format.)

Data Sources and Methodology

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3779202/

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera

https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/john-snow-and-cholera-outbreak

The information presented was compiled from a variety of reputable historical sources focusing on the history of medicine and public health. Key contributors were selected based on their significant and demonstrable influence on the development, acceptance, or rejection of the miasma theory. The selection criteria prioritized individuals whose work directly addressed or significantly impacted the theory’s trajectory. Limitations include the inherent biases present in historical records and the potential for incomplete documentation of all relevant contributions.

Visual Representation of Influence (Placeholder – Requires JavaScript/Canvas implementation)

A visual representation (e.g., a network graph) showing the relationships and influences between the key contributors would be included here. This would illustrate how ideas and research flowed between individuals and contributed to the overall development of the miasma theory. (Implementation omitted due to limitations of this text-based response format.)

Bias and Limitations

The selection of key contributors inherently involves a degree of bias, as it relies on the availability and accessibility of historical data. Some individuals who may have made important, albeit less documented, contributions might be underrepresented. Furthermore, the interpretation of their contributions is influenced by modern understandings of disease transmission, which might not fully capture the nuances of the scientific thinking of their time.

The limitations of historical data sources, such as incomplete records and potential biases in historical accounts, must be acknowledged, impacting the completeness and objectivity of the presented information.

Geographical Spread and Acceptance

The miasma theory, while ultimately superseded by the germ theory, enjoyed a significant period of dominance in shaping public health practices and medical understanding across various regions. Its acceptance, however, wasn’t uniform, varying considerably based on a complex interplay of socio-cultural, political, economic, and scientific factors. Examining the geographical spread and acceptance of the miasma theory reveals fascinating insights into the historical development of medical thought and public health interventions.

Regions of Wide Acceptance

The miasma theory’s prevalence varied across geographical locations and time periods. Several regions exhibited widespread acceptance before the germ theory gained prominence. Understanding the specific contexts of this acceptance requires examining both the timeframe and available primary source documentation.

- Europe (18th and 19th centuries): Much of Europe, particularly Western Europe, embraced the miasma theory as the primary explanation for disease. This acceptance is evident in numerous public health initiatives focused on sanitation improvements, such as the construction of better sewage systems and the promotion of cleanliness. The timeframe extends roughly from the mid-18th century to the late 19th century, gradually declining as the germ theory gained traction.

A primary source supporting this is the extensive body of writings by Edwin Chadwick, whose influential 1842 report, “Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain,” strongly advocated for sanitation improvements based on miasma theory. His work directly influenced public health policy across Europe.

- North America (18th and 19th centuries): Similar to Europe, North America saw widespread acceptance of the miasma theory, particularly in urban centers grappling with issues of sanitation and disease outbreaks. The timeframe mirrors that of Europe, with a gradual shift towards germ theory in the late 19th century. Public health initiatives reflected this belief, focusing on improving drainage, waste disposal, and overall cleanliness in cities.

While specific primary sources documenting widespread acceptance across the entire continent are difficult to isolate, the numerous local and regional health reports from this period consistently reflect the prevailing miasma-based understanding of disease causation.

- Parts of Asia (18th and 19th centuries): While less thoroughly documented than in Europe and North America, the miasma theory influenced public health practices in certain parts of Asia. For instance, the focus on cleanliness and hygiene in some Chinese medical traditions can be interpreted as reflecting aspects of the miasma theory. However, the extent of its influence and specific timeframes require further research.

The lack of readily available translated primary source material poses a challenge in comprehensively assessing the adoption of the miasma theory in this region.

Regions of Rejection or Limited Acceptance

Not all regions uniformly accepted the miasma theory. Some areas showed resistance or limited adoption, highlighting the complex interplay of local factors influencing medical beliefs.

- Certain Indigenous Communities in the Americas: Many Indigenous communities in the Americas possessed their own sophisticated medical systems and understanding of disease, often unrelated to the miasma theory. Their traditional practices and beliefs often clashed with the European-imported miasma theory, leading to resistance or limited adoption. The timeframe spans the entire period of colonial contact and beyond, as traditional healing practices persisted despite the introduction of European medical ideas.

A lack of written records from these communities makes a precise analysis challenging.

- Some regions of Africa: Similar to the Americas, certain regions of Africa maintained their indigenous medical traditions, which were often not compatible with the miasma theory. The timeframe is similarly broad, extending throughout the colonial period and beyond. The reasons for resistance include the pre-existence of effective traditional healing practices, the distrust of colonial medicine, and the cultural dissonance between European and African medical systems.

Influencing Factors

The adoption or rejection of the miasma theory was influenced by a complex web of factors. The following table summarizes these influences:

| Category | Factor | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-cultural factors | Religious beliefs | In some regions, religious interpretations of disease influenced the acceptance or rejection of the miasma theory. For instance, certain religious views might attribute disease to divine punishment, rendering the miasma theory less relevant. |

| Political factors | Government policies | The British government’s response to cholera outbreaks in the 19th century, influenced by the miasma theory, led to significant public health initiatives focused on sanitation improvements. These policies demonstrate the theory’s direct impact on government actions. |

| Economic factors | Urbanization | Rapid urbanization led to overcrowded living conditions, fostering disease outbreaks. This, in turn, fueled the acceptance of the miasma theory as a plausible explanation for these outbreaks, prompting the implementation of sanitation measures. |

| Scientific factors | Competing theories | The emergence of the germ theory provided a competing explanation for disease, gradually undermining the miasma theory’s dominance. Advancements in microscopy played a crucial role in shifting scientific consensus. |

Geographical Map Design

(Note: A physical choropleth map cannot be created within this text-based format. The following is a description of how such a map would be constructed.)A choropleth map illustrating the geographical spread of the miasma theory’s acceptance would use a color gradient across Europe and the Americas between 1700 and 1900. Darker shades of green would represent high acceptance, lighter shades of green would represent moderate acceptance, yellow would indicate low acceptance, and red would signify rejection.

The legend would clearly define these color gradients and specify the time periods. Major cities (London, Paris, New York, etc.), major ports, rivers, and mountain ranges would be indicated. The map would reveal a high concentration of dark green in major European cities during the 18th and early 19th centuries, gradually transitioning to lighter shades and yellow as the germ theory gained acceptance.

North America would show a similar pattern, albeit with a potentially less uniform distribution due to variations in urbanization and access to information. Areas with significant indigenous populations might display pockets of red, reflecting the resistance to the miasma theory.The map would visually demonstrate the uneven spread of the miasma theory, with high acceptance in densely populated urban centers and relatively lower acceptance in rural areas and regions with strong pre-existing medical traditions.

Regional variations would be apparent, reflecting differences in sanitation infrastructure, political responses to disease outbreaks, and the dissemination of scientific knowledge. The map would highlight the temporal shift in acceptance, showing a gradual decline in the miasma theory’s dominance from the mid-19th century onwards. Notable anomalies could include areas where resistance to the theory persisted despite significant urban development and disease outbreaks.

Comparative Analysis

Comparing the spread of the miasma and germ theories reveals significant differences. In Europe, the miasma theory spread relatively quickly due to its apparent correlation with observable environmental factors like foul smells and poor sanitation. Its acceptance was reinforced by influential figures and government policies promoting sanitation improvements. The germ theory, in contrast, spread more slowly, initially facing resistance from established medical authorities.

Its acceptance required significant advancements in microscopy and experimental methodology. In North America, a similar pattern is observed, with the miasma theory gaining initial traction due to the readily apparent link between filth and disease, while the germ theory’s acceptance required a more protracted period of scientific debate and evidence accumulation. The rate of adoption differed substantially, with the miasma theory achieving widespread acceptance relatively quickly, while the germ theory’s adoption was a gradual process.

The manner of adoption also differed, with the miasma theory spreading through a combination of practical observation, public health initiatives, and influential figures, whereas the germ theory’s spread relied more heavily on scientific experimentation and the dissemination of research findings.

The Role of Public Health Practices

The miasma theory, despite its flawed understanding of disease transmission, significantly influenced public health practices during the 18th and 19th centuries. The belief that foul air caused illness led to a range of interventions aimed at improving environmental sanitation and reducing perceived sources of bad smells. While ultimately ineffective in preventing many diseases, these measures did contribute to some improvements in public health, albeit indirectly and often unintentionally.

Public Health Measures Based on the Miasma Theory

The implementation of public health measures during the peak of the miasma theory’s influence stemmed from the belief that foul-smelling air, or miasma, was the primary cause of disease. This led to a focus on environmental improvements intended to eliminate or mitigate these perceived noxious emanations. The following table details several specific examples.

| Measure | Location | Timeframe | Target Disease(s) | Rationale based on Miasma Theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved Sewerage Systems | London, England; Paris, France; many other European cities | 18th-19th centuries | Cholera, Typhoid, Dysentery | Removal of stagnant, foul-smelling water and waste believed to be a source of miasma. |

| Street Cleaning and Waste Removal | Numerous cities across Europe and North America | 18th-19th centuries | Various infectious diseases | Removal of visible sources of putrefaction and unpleasant odors to reduce miasma. |

| Quarantine of Infected Areas | Various port cities worldwide | 18th-19th centuries | Cholera, Yellow Fever, Plague | Isolation of areas perceived to be sources of miasma to prevent its spread. |

| Improved Ventilation in Buildings | Hospitals, homes, and public buildings in Europe and North America | 18th-19th centuries | Various respiratory illnesses | Improved airflow to dilute or eliminate the concentration of miasma. |

| Public Parks and Green Spaces | Many major cities in Europe and North America | 19th century | General improvement of public health | “Fresh air” was believed to counteract the effects of miasma. |

Effectiveness of Miasma-Based Public Health Measures

While miasma-based public health measures often lacked a direct impact on disease control, they inadvertently contributed to improved sanitation in some instances. Improved sewerage systems, for example, did reduce the incidence of waterborne diseases, although not because of the elimination of miasma, but due to the reduced contamination of water sources. However, the effectiveness of these measures was limited by the flawed underlying theory.

Quarantine measures, while sometimes effective in slowing the spread of diseases, were often inconsistently implemented and hampered by a lack of understanding of disease transmission mechanisms. The absence of reliable mortality data specifically linked to miasma-related interventions makes it difficult to definitively assess their overall success. Furthermore, the focus on environmental factors often overshadowed other crucial public health concerns, such as personal hygiene and food safety.

The overall impact of these measures was therefore mixed, with some positive unintended consequences alongside limited direct success in controlling disease spread.

Comparison of Miasma-Based and Modern Public Health Interventions

The following table compares and contrasts miasma-based public health measures with three modern interventions: vaccination, improved sanitation based on germ theory, and public health campaigns.

| Aspect | Miasma-Based Measures | Vaccination | Germ Theory-Based Sanitation | Public Health Campaigns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying Scientific Principles | Miasma theory (foul air causes disease) | Germ theory (microbes cause disease) | Germ theory (microbes spread through contaminated water and waste) | Behavioral science, epidemiology |

| Methods of Implementation | Environmental improvements (sewerage, street cleaning) | Injection of attenuated or killed pathogens | Improved sewage systems, water treatment, hygiene practices | Education, awareness raising, behavior change strategies |

| Effectiveness | Limited direct impact, some indirect benefits | Highly effective in preventing many infectious diseases | Highly effective in reducing waterborne and sanitation-related diseases | Variable effectiveness depending on the campaign and target behavior |

| Target Population | General population | Specific populations at risk | General population | Specific populations at risk or general population |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Variable, often expensive in terms of infrastructure | Highly cost-effective in the long run | High initial investment, cost-effective in the long run | Relatively low cost, high potential for impact |

| Long-Term Impact | Limited, indirect impact on public health | Significant reduction in morbidity and mortality from many infectious diseases | Significant improvement in public health | Significant impact on behavior change and disease prevention |

Societal Impact of Miasma Theory-Based Public Health Measures

The societal impact of miasma theory-based public health measures was complex and multifaceted. While initiatives like improved sanitation had long-term positive effects on public health, their implementation often favored wealthier communities. Poorer neighborhoods frequently lacked access to improved sanitation, leading to health disparities. Economically, the construction of new infrastructure (sewer systems, etc.) stimulated economic growth in some areas, but placed a burden on municipal budgets.

Public perception of health shifted towards a greater emphasis on environmental cleanliness, though the underlying cause of disease remained misunderstood. Unintended consequences included the displacement of some communities due to urban renewal projects aimed at improving sanitation.

Ethical Considerations of Miasma-Based Public Health

Lack of Informed Consent

Public health measures were often implemented without the informed consent of the affected populations.

Infringement on Individual Liberties

Quarantine measures, for instance, restricted individual freedom of movement and association.

Social Injustice

The unequal distribution of sanitation improvements led to health disparities between wealthier and poorer communities.

Misallocation of Resources

Resources were often spent on measures that were ultimately ineffective in controlling disease.

Case Study: London’s Response to the Cholera Outbreaks

London experienced several devastating cholera outbreaks during the 19th century. The city’s response, largely based on the miasma theory, focused on improving sanitation and removing perceived sources of foul air. This included the construction of improved sewerage systems and the expansion of street cleaning initiatives. While these measures did not directly prevent cholera outbreaks (the true cause, contaminated water, was unknown), they contributed to improvements in overall sanitation and public health.

The long-term impact included a significant upgrade to London’s water and sewage infrastructure, although the unequal distribution of these improvements continued to create health disparities across the city. The legacy of these responses, however, highlights the importance of understanding the true causes of disease in developing effective public health strategies.

The Decline of the Miasma Theory

The long-held belief in miasma theory, attributing disease to bad air, gradually eroded throughout the 19th century as scientific advancements and epidemiological observations challenged its fundamental tenets. The shift towards a germ theory of disease was not a sudden revolution but a gradual process involving multiple converging lines of evidence.The decline of the miasma theory was a complex process intertwined with significant scientific breakthroughs and a changing understanding of disease transmission.

Key discoveries directly contradicted the miasma’s core assumptions, leading to its eventual replacement by the germ theory.

The Contributions of Germ Theory

The emergence of the germ theory, primarily championed by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, provided a compelling alternative explanation for infectious diseases. Pasteur’s experiments on fermentation and the role of microorganisms in spoilage, coupled with his work on pasteurization, demonstrated the link between specific microorganisms and disease processes. Koch’s postulates, a set of criteria for establishing a causal relationship between a microorganism and a disease, provided a rigorous framework for identifying the causative agents of various illnesses.

This shift in understanding moved the focus from environmental factors like “bad air” to the specific microorganisms inhabiting the body and their role in causing disease. The discovery of disease-causing bacteria like

- Bacillus anthracis* (anthrax) and

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis* (tuberculosis) solidified the evidence supporting the germ theory, directly undermining the miasma theory’s power.

Experimental Evidence Contradicting Miasma

Several key experiments and observations challenged the miasma theory’s power. For instance, the work of John Snow on cholera outbreaks in London demonstrated a strong correlation between contaminated water sources and disease spread, a finding inconsistent with the miasma theory’s emphasis on airborne pollutants. Snow’s meticulous mapping of cholera cases and his identification of the Broad Street pump as the source of contamination provided compelling evidence for a waterborne, rather than airborne, transmission route.

This groundbreaking work significantly contributed to the shift away from miasma-based explanations. Furthermore, advancements in microscopy allowed scientists to observe microorganisms, providing visual evidence of the entities responsible for causing illness, further strengthening the germ theory.

The Transition to Germ-Based Understanding

The transition from miasma-based to germ-based understanding of disease wasn’t immediate. Many practitioners continued to adhere to miasma theory for a considerable period, particularly in areas with limited access to the latest scientific advancements. However, the accumulating evidence from laboratory experiments, epidemiological studies, and improved sanitation practices increasingly favored the germ theory. The successful implementation of germ-based public health interventions, such as sterilization techniques and vaccination, further solidified the acceptance of the germ theory and contributed to the decline of miasma theory.

The development of effective treatments and preventative measures based on germ theory dramatically improved public health outcomes, providing irrefutable evidence of its superiority over the miasma theory.

Lingering Influences of Miasma Theory

The miasma theory, though ultimately incorrect in its central premise, left a surprisingly enduring legacy on public health practices and thinking. While the germ theory revolutionized our understanding of disease transmission, several key aspects of the miasma theory’s focus on environmental sanitation continue to influence modern approaches to disease prevention and control. This section explores these lingering influences, examining their impact on environmental hygiene, vector control, public perception, and the ongoing debate surrounding environmental factors in disease etiology.

Environmental Hygiene’s Continued Relevance

The miasma theory’s emphasis on clean air and water, though based on a flawed understanding of disease causation, inadvertently spurred significant advancements in sanitation infrastructure. The belief that foul-smelling air and contaminated water caused disease led to initiatives such as improved sewage systems, water purification methods, and the promotion of personal hygiene. These practices, although initially motivated by the incorrect miasma theory, significantly reduced the incidence of waterborne and air-borne diseases.

For instance, the implementation of improved sanitation systems in the 19th and 20th centuries dramatically decreased the prevalence of cholera and typhoid fever in many parts of the world. While precise quantification is challenging due to the interplay of multiple factors, the correlation between improved sanitation and reduced incidence of these diseases is well-established (e.g., studies on the impact of sanitation improvements on cholera outbreaks in developing countries).

Vector Control’s Indirect Origins

The miasma theory’s association of disease with foul-smelling environments indirectly contributed to the development of vector control strategies. While the theory incorrectly attributed disease to the air itself, the focus on cleaning up stagnant water and eliminating breeding grounds for insects inadvertently helped control the spread of diseases transmitted by vectors such as mosquitoes and flies. The connection is evident in the control of malaria, where draining swamps and eliminating mosquito breeding sites became common practices, even before the discovery of theAnopheles* mosquito as the vector.

Similarly, efforts to improve sanitation and reduce filth, driven by miasma theory, indirectly aided in the control of diseases like typhus, spread by lice thriving in unsanitary conditions.

Public Perception and Preventative Measures

The lingering belief in the importance of environmental factors in disease causation continues to shape public health messaging and the acceptance of preventative measures. While the germ theory clarifies the role of microorganisms, the public’s understanding often incorporates elements of the miasma theory, leading to a greater acceptance of measures such as handwashing, air purification, and environmental protection. This ingrained association between a clean environment and good health facilitates the acceptance of public health interventions aimed at improving sanitation and environmental quality.

For example, public health campaigns often emphasize the importance of clean air and water, echoing the central tenets of the miasma theory, even while simultaneously promoting vaccination and other germ-theory-based interventions.

A Timeline of the Shift from Miasma to Germ Theory

| Date | Event | Impact on Public Health Practices ||————|———————————————|——————————————————————-|| 1854 | John Snow’s cholera study | Focused attention on water contamination as a disease vector, despite the prevailing miasma theory.

|| 1861 | Pasteur’s germ theory experiments | Began to shift the focus from environmental factors to microbial agents. || 1876 | Koch’s postulates established | Provided a framework for identifying the causative agents of infectious diseases.

|| Late 1800s | Development of sanitation infrastructure | Continued improvement in sanitation, driven by both miasma theory and early germ theory. || 1900s onward | Advances in microbiology and immunology | Led to the development of vaccines, antibiotics, and improved disease surveillance. |

Case Studies: Public Health Interventions

The Great Stink of London (1858) prompted the construction of a modern sewage system, a response directly influenced by the miasma theory’s association of foul odors with disease. While the underlying cause of cholera was not yet understood, the immediate aim was to improve the environment by removing the offensive smells. Similarly, cholera outbreaks, such as the one studied by John Snow in 1854, while eventually linked to contaminated water by Snow’s epidemiological work, were initially approached through environmental measures based on the miasma theory, such as cleaning up the streets and improving drainage.

Comparative Analysis: Miasma vs. Germ Theory

| Aspect | Miasma Theory | Germ Theory | Effectiveness ||——————————|———————————————–|————————————————|————————————————-|| Disease Causation | Foul air, bad smells, environmental pollution | Microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, etc.) | Germ theory is far more accurate.

|| Prevention Strategies | Improving sanitation, drainage, air quality | Vaccination, hygiene, antibiotic treatment | Germ theory-based strategies are generally more effective. || Success in Disease Control | Limited success, mostly indirect improvements | Significant reduction in infectious diseases | Germ theory has led to much greater success.

|

Ongoing Debates on Environmental Factors in Disease

| Debate Topic | Pro-Environmental Factor Argument | Anti-Environmental Factor Argument | Evidence Required for Each Side ||———————————|—————————————————————–|—————————————————————–|——————————————————————-|| Role of Air Pollution in Asthma | Air pollution exacerbates asthma symptoms; particulate matter and pollutants trigger inflammation in the airways.

| Asthma is primarily a genetic predisposition; environmental factors are secondary triggers. | Longitudinal studies linking specific pollutants to asthma incidence and severity; mechanistic studies showing how pollutants trigger asthma attacks. || Impact of Water Quality on Cholera | Contaminated water is the primary vector for cholera transmission; poor water quality leads to increased incidence. | Other factors like sanitation and hygiene play a more significant role; water quality is only one factor.

| Epidemiological studies demonstrating a clear correlation between water quality and cholera outbreaks; controlled experiments showing the role of contaminated water in transmission. || Influence of Housing Conditions on Disease Transmission | Overcrowding and poor housing conditions facilitate disease transmission due to increased contact and reduced hygiene. | Socioeconomic factors are the primary drivers; housing conditions are a reflection of poverty, not a direct cause.

| Studies demonstrating increased disease transmission rates in overcrowded and poorly maintained housing; experimental designs isolating the effect of housing conditions on disease transmission. |

Cultural and Social Impacts

The miasma theory, despite its ultimately flawed premise, profoundly shaped societal attitudes towards disease and profoundly impacted urban development and public health practices for centuries. Its influence extended far beyond the realm of scientific discourse, permeating cultural beliefs and shaping public responses to outbreaks and epidemics. The theory’s pervasive acceptance, fueled by fear and a lack of understanding of germ theory, led to significant, albeit often misguided, efforts to improve living conditions.The miasma theory’s societal impact is evident in the significant changes it spurred in urban planning and sanitation.

The belief that foul air caused disease led to widespread efforts to improve ventilation, drainage, and waste disposal. Cities across Europe and North America undertook ambitious projects to widen streets, improve sewage systems, and create public parks, all driven by the desire to improve air quality and prevent disease. While these improvements ultimately benefited public health, they were conceived and implemented within the framework of a flawed scientific understanding.

Urban Planning and Sanitation Initiatives

The belief that bad smells caused disease directly influenced urban design. For example, the construction of wider streets, particularly in densely populated areas, was intended to increase air circulation and disperse noxious fumes. Similarly, improved sewage systems and the development of more effective drainage networks were considered crucial to removing sources of putrid odors believed to be the cause of disease.

These improvements, while not directly addressing the true causes of infectious diseases, undeniably contributed to improved public health by reducing exposure to pathogens and improving overall living conditions. The grand boulevards of Paris, for example, a product of Baron Haussmann’s urban renewal program, were partly motivated by the desire to improve ventilation and reduce the spread of disease according to the prevailing miasma theory.

Public Perception of Disease and Health

The miasma theory profoundly influenced public perception of disease and health, fostering a strong association between bad smells and illness. This led to a widespread belief that avoiding unpleasant odors was a key strategy for preventing disease. People associated specific smells with specific diseases, linking, for example, the stench of decaying matter with cholera. This belief led to practices like the use of strong perfumes and disinfectants, such as carbolic acid, in an attempt to mask or neutralize the supposed disease-causing odors.

While these practices were largely ineffective in preventing the spread of disease, they reflected the deep-seated belief in the miasma theory and its influence on everyday life.

The Role of Fear and Misinformation

Fear and misinformation played a crucial role in the acceptance and spread of the miasma theory. The inability to explain the causes of many diseases fueled public anxiety and made the miasma theory, with its seemingly simple explanation, appealing. The vivid descriptions of putrid air and its association with death reinforced fear and mistrust, contributing to the widespread acceptance of the theory.

The lack of accurate information and the reliance on anecdotal evidence further perpetuated the belief in the miasma theory, delaying the acceptance of the germ theory for several decades. The fear of contagion, often linked to the imagined foul air, led to social isolation and stigmatization of individuals and communities perceived to be sources of bad smells.

Specific Examples of Miasma-Related Diseases

The miasma theory, while ultimately incorrect, profoundly shaped the understanding and treatment of numerous diseases for centuries. Many illnesses with poorly understood causes were attributed to bad air, leading to practices that, while sometimes ineffective, reflected a genuine attempt to improve public health. Examining specific examples reveals the limitations of the miasma theory and highlights the transformative shift brought about by the germ theory.

Cholera

Cholera, a severe diarrheal illness caused by the bacterium

- Vibrio cholerae*, was widely believed to be miasma-related. The characteristic foul odor associated with cholera outbreaks reinforced this belief. Symptoms, such as severe vomiting and dehydration, were attributed to the inhalation of noxious air emanating from decaying organic matter and stagnant water. Treatments focused on improving air quality, using disinfectants like lime, and avoiding areas deemed to be sources of bad air.

The germ theory revolutionized the understanding of cholera, pinpointing

- Vibrio cholerae* as the causative agent and leading to effective interventions such as sanitation improvements, clean water access, and the development of oral rehydration therapy. The shift from miasma-based treatments to targeted antimicrobial interventions dramatically reduced cholera mortality rates.

Typhus

Typhus, a bacterial infection spread by lice, was also linked to miasma. Overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions, often associated with typhus outbreaks, were considered to produce the miasma responsible for the disease. The high fever, rash, and delirium characteristic of typhus were seen as direct consequences of inhaling contaminated air. Treatments focused on improving ventilation and removing sources of putrid odors.

The discovery ofRickettsia prowazekii*, the bacterium responsible for typhus, and the understanding of its transmission through lice completely altered the approach to this disease. Improved sanitation, delousing campaigns, and the eventual development of antibiotics dramatically altered the course and prognosis of typhus.

Yellow Fever

Yellow fever, a viral hemorrhagic fever transmitted by mosquitoes, was another illness widely attributed to miasma. The disease’s association with swampy, humid areas fueled the belief in miasma as the cause. Symptoms, such as jaundice, fever, and internal bleeding, were seen as effects of the “bad air” emanating from these environments. Efforts to combat yellow fever under the miasma theory focused on draining swamps and improving air circulation.

The later identification of the yellow fever virus and theAedes aegypti* mosquito as the vector transformed the disease’s management. Mosquito control measures, such as insecticide spraying and eliminating breeding grounds, became central to prevention, along with vaccination campaigns. This illustrates the profound difference between a treatment approach based on speculation about “bad air” and one based on a precise understanding of disease transmission.

Bubonic Plague

While not solely attributed to miasma, the bubonic plague’s association with unsanitary conditions reinforced the miasma theory. The disease’s devastating effects and its association with overcrowded, impoverished areas strengthened the belief that foul air was the primary cause. The characteristic buboes (swollen lymph nodes) and other symptoms were attributed to the inhalation of miasma. Early treatments, therefore, focused on improving sanitation and air quality.

The discovery ofYersinia pestis* as the causative agent and the understanding of its transmission via fleas living on rats revolutionized plague management. Quarantine measures, rodent control, and antibiotic treatments dramatically improved outcomes, highlighting the crucial difference between miasma-based approaches and those grounded in bacteriological knowledge.

Notable Experiments and Studies

While the miasma theory lacked the rigorous scientific methodology of later germ theory, several experiments and studies attempted to understand the relationship between foul air and disease. These investigations, though flawed by modern standards, offer valuable insight into the scientific thinking of the time and the gradual shift towards a more accurate understanding of disease transmission. Many studies focused on observation and correlation, rather than controlled experiments, reflecting the limitations of the available technology and understanding of scientific method.

Many experiments during this era focused on the observation of environmental factors and their correlation with disease outbreaks. Researchers often noted the presence of foul smells, stagnant water, and decaying matter in areas with high disease incidence. However, the inability to isolate specific causative agents hindered the development of effective preventative measures. The lack of sophisticated laboratory equipment and sterile techniques also significantly impacted the reliability of these studies.

John Snow’s Cholera Investigation

John Snow’s investigation of the 1854 cholera outbreak in London stands out as a notable exception to the prevailing miasma-based thinking. While Snow still believed in the influence of foul air, his meticulous mapping of cholera cases revealed a strong correlation with a specific water pump on Broad Street. His findings, which implicated contaminated water as the primary source of the outbreak, provided early evidence challenging the exclusive focus on atmospheric miasma.

Snow’s work involved detailed record-keeping, geographical mapping, and the systematic collection of data on cases, deaths, and water sources. This approach, though not directly refuting miasma theory, shifted attention towards a more specific environmental factor—contaminated water—as a crucial vector for disease transmission. The methodology involved detailed case mapping, interviews with residents to identify water sources, and statistical analysis to demonstrate the association between the Broad Street pump and cholera cases.

This pioneering approach foreshadowed epidemiological methods used in modern public health investigations. However, the lack of understanding of bacterial agents limited the ability to definitively prove causation.

Experiments on Air Quality and Disease

Numerous experiments attempted to link specific components of “bad air” to disease. These often involved exposing animals or humans to various gases or substances believed to contribute to miasma. The methodologies were often rudimentary, lacking controlled environments and standardized measurement techniques. Findings were often inconclusive or easily interpreted to support existing biases. For example, some researchers might expose animals to putrid air and observe respiratory issues, concluding that the foul air caused the illness.

However, these experiments lacked controls and often failed to consider other potential factors, such as pre-existing conditions or exposure to other pathogens. The lack of sophisticated analytical tools also limited the ability to identify and quantify specific components within the air samples.

Limitations and Biases in Early Investigations

The limitations of these studies were substantial. The lack of understanding of microorganisms and their role in disease transmission was a major constraint. Furthermore, the rudimentary technology of the time hampered accurate measurements and controlled experiments. Confirmation bias also played a significant role; researchers often designed studies and interpreted results to confirm their pre-existing beliefs in the miasma theory.

The prevailing societal and cultural beliefs about disease also influenced the design and interpretation of research. For instance, the belief that poverty and poor sanitation caused disease, though partly true, often led to neglecting the role of specific pathogens in disease transmission. The lack of statistical rigor and controlled experimental designs further limited the validity of many of these studies.

The Scientific Method and Miasma

The miasma theory, while ultimately incorrect, represented a significant attempt to understand disease transmission through the lens of the scientific method as it was understood in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its proponents meticulously documented observations, formulated hypotheses, and, to a degree, tested these hypotheses, although with significant limitations compared to modern standards. The process, however, lacked the rigor and sophistication that would later characterize the germ theory revolution.Observations Supporting the Miasma TheoryThree key observations underpinned the miasma theory.

Firstly, the strong correlation between foul-smelling air in areas with poor sanitation and the prevalence of disease was widely noted. For example, the stench emanating from overflowing cesspools and decomposing waste in densely populated urban areas was consistently linked to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. Secondly, the observation that diseases were more prevalent in poorly ventilated, overcrowded spaces further strengthened the belief in noxious air as the primary cause.

This was observed in hospitals, prisons, and slums. Thirdly, the improvement in public health outcomes following sanitation initiatives, such as improved drainage and waste disposal, provided seemingly compelling evidence in support of the miasma theory. Figures like John Snow, while ultimately pivotal in shifting the paradigm towards germ theory, initially worked within the framework of miasma, observing the link between contaminated water sources and cholera outbreaks.Flaws in the Application of the Scientific Method During the Miasma Theory Era

| Flaw | Explanation | Improved Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of controlled experiments | Experiments designed to test the miasma theory often lacked proper control groups. Researchers might observe disease prevalence in areas with poor sanitation but failed to compare these findings to similar areas with better sanitation to isolate the effects of the “miasma.” | Implementing controlled experiments, with comparable control and experimental groups, would have allowed researchers to isolate the effect of “miasma” more accurately. This would involve carefully selecting areas with similar populations and demographics but differing sanitation levels, allowing for a more robust comparison of disease prevalence. |

| Subjective observation | Observations were often based on subjective assessments of smells and general environmental conditions. Quantitative data, such as mortality rates, were collected but not always systematically linked to specific environmental factors in a controlled manner. | Employing objective measurements and quantitative data collection methods would have enhanced the accuracy and reliability of the findings. This would include detailed measurements of air quality, precise mapping of disease outbreaks, and rigorous statistical analysis to establish correlations between environmental factors and disease prevalence. |

| Limited technology | The lack of advanced microscopy and other laboratory techniques prevented researchers from identifying the actual causative agents of diseases. They could observe the effects of poor sanitation, but not the underlying mechanisms. | The development and application of advanced technologies such as microscopy would have allowed researchers to visualize microorganisms and understand their role in disease transmission. This would have significantly improved the understanding of disease causation, leading to a more accurate and complete theory. |

Comparison of Scientific Methodologies: Miasma vs. Germ TheoryData Collection: The miasma theory relied heavily on qualitative data, such as observations of smells and descriptions of environmental conditions. Germ theory, in contrast, incorporated quantitative data like bacterial counts and mortality statistics.Experimental Design: Miasma theory predominantly used observational studies, correlating disease prevalence with environmental factors. Germ theory utilized controlled experiments, such as Robert Koch’s postulates, to establish a causal link between specific microorganisms and diseases.Technological Advancements: The development of the microscope was crucial in shifting the paradigm from miasma to germ theory.

This allowed scientists to observe and identify microorganisms, providing direct evidence for the germ theory.Peer Review and Dissemination: The dissemination of scientific findings during the miasma era was less formal than in the germ theory era. The rise of scientific journals and societies fostered a more rigorous peer-review process in the germ theory era, enhancing the quality and reliability of scientific knowledge.

Miasma Theory and its Predecessors

The miasma theory, while ultimately incorrect, didn’t emerge in a vacuum. Its development was a gradual process, built upon and reacting against centuries of evolving understanding (or misunderstanding) of disease causation. Tracing its intellectual lineage reveals a fascinating interplay of ancient beliefs, philosophical shifts, and nascent scientific inquiry.The understanding of disease causation has undergone a significant transformation throughout history.

Early explanations were often intertwined with religious, superstitious, and philosophical frameworks, gradually giving way to more empirical observations and, eventually, the germ theory of disease.

Ancient and Medieval Conceptions of Disease

Ancient civilizations often attributed disease to imbalances in the body’s humors, divine punishment, or the influence of evil spirits. The Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of medical texts from ancient Greece, while emphasizing observation and natural causes, still included concepts like an imbalance of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) as a primary cause of illness.

This humoral theory, though not directly a precursor to miasma, shared the focus on environmental factors influencing health, albeit in a different way. Medieval Europe saw a continuation of these beliefs, often interwoven with religious interpretations, where disease was viewed as divine retribution or the work of demonic forces. The Black Death, for example, was widely interpreted through this lens, with little understanding of its actual transmission.

The Rise of Environmentalism in Medical Thought

The Renaissance and Enlightenment periods saw a shift towards a more naturalistic view of the world, impacting medical thinking. While the humoral theory persisted, observations of the correlation between poor sanitation and disease outbreaks became increasingly prominent. The association between foul smells and illness, though not yet understood mechanistically, gained traction. This period laid the groundwork for the miasma theory by emphasizing the importance of environmental factors in disease causation, moving away from purely supernatural or humoral explanations.

Early Modern Understandings of Disease and the Miasma Theory’s Emergence

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the miasma theory had fully taken shape. While still lacking the precision of germ theory, it represented a significant step forward in acknowledging the role of the environment in disease transmission. The theory proposed that diseases were caused by “bad air,” a noxious miasma emanating from decaying organic matter, stagnant water, and other sources of foul odors.

This marked a clear departure from purely supernatural or humoral explanations, emphasizing the tangible, albeit misinterpreted, environmental factors. The miasma theory, therefore, was a product of its time, a synthesis of growing environmental awareness and limited understanding of microbiology. It was an attempt to explain observed correlations, even if the underlying mechanism was fundamentally flawed.

Artistic and Literary Depictions of the Miasma Theory

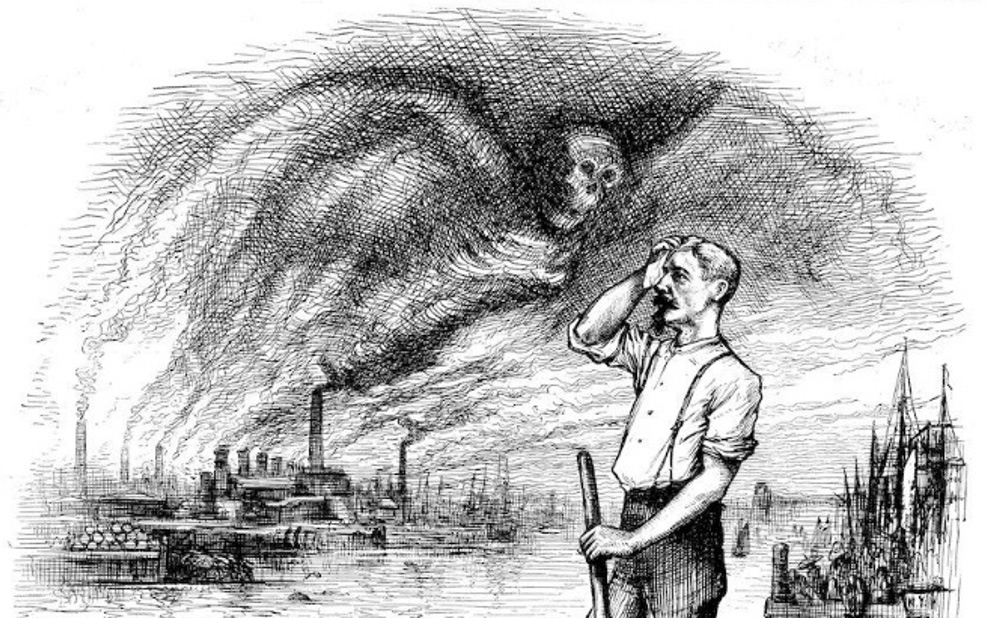

The miasma theory, while ultimately scientifically incorrect, profoundly impacted the cultural imagination of the 17th to 19th centuries. Its pervasive influence is evident in the artistic and literary works of the period, shaping not only how disease was visually represented but also how it was understood within a broader social and moral context. These depictions often went beyond a simple representation of illness, reflecting deeper anxieties about societal decay, divine judgment, and the limitations of human understanding in the face of widespread suffering.

Visual Depictions in Art, When was miasma theory made

Artists of the Baroque and Romantic periods frequently employed visual elements to convey the miasma theory’s central concept: the notion that foul air caused disease. The dark, swirling clouds and fog often depicted in paintings and prints symbolized the putrid air believed to carry pestilence. Grim-faced figures, often emaciated and pale, represented the victims of disease, their suffering a direct consequence of the miasmatic environment.

The miasma theory, a now-discredited belief linking disease to bad air, held sway for centuries, its origins stretching back to antiquity. Understanding its historical context requires grasping the limitations of past scientific understanding, a process much like mastering music theory; for insights on structuring your musical creations, check out this helpful Reddit resource: how to make songs wiht music theory reddit.

Just as miasma theory was eventually replaced by germ theory, musical understanding evolves through structured learning.

Decaying landscapes, littered with refuse and overflowing with disease, symbolized the environmental corruption that was seen as a breeding ground for illness.

| Visual Element | Symbolic Association | Example Artwork/Artist (if known) |

|---|---|---|

| Dark, swirling clouds and fog | Putrid air, disease, death, the unseen threat | Many Romantic landscape paintings featuring atmospheric perspective, though specific examples focusing on miasma are difficult to definitively identify. The overall sense of oppressive atmosphere in many works is indicative. |

| Grim-faced, emaciated figures | Victims of disease, suffering, the fragility of life | Paintings depicting plague scenes, often found in religious or historical contexts. Many anonymous works from this period showcase this imagery. |

| Decaying landscapes, overflowing with refuse | Environmental corruption, breeding ground for disease, moral decay | Some Baroque paintings depicting scenes of urban squalor and decay may implicitly reflect this, although a direct link to miasma theory requires further contextual research. |

| Strong contrasts of light and shadow | Highlighting the dichotomy between health and disease, emphasizing the unseen threat | Chiaroscuro techniques prevalent in Baroque art could be interpreted as visually representing the hidden nature of miasma and its deadly effects. |

Literary Representations

Literature of the period mirrored the visual representations, using vivid imagery and metaphorical language to convey the concept of miasma. Authors employed similes and metaphors to describe the foul air, comparing it to noxious fumes, stagnant swamps, or decaying flesh. The sensory experience of miasma—the suffocating smell, the oppressive atmosphere—was frequently evoked to create a sense of dread and impending doom.

For instance, the pervasive stench and suffocating air in many descriptions of plague-stricken cities created a powerful sense of miasma’s deadly presence.

In Daniel Defoe’s

A Journal of the Plague Year*, the pervasive stench is a constant, inescapable presence

“The stench was such as cannot be described.” This simple sentence encapsulates the overwhelming, tangible nature of miasma as perceived at the time. The lack of further description is itself powerful, hinting at a sensory experience beyond words.

Symbolic Meaning and Cultural Significance

The symbolic meaning of miasma in art and literature extended beyond a simple representation of disease. It became a powerful symbol of moral decay, associating disease with societal ills such as poverty, overcrowding, and poor sanitation. Miasma also represented social inequality, as the poor and marginalized were disproportionately affected by disease. Some interpretations even linked miasma to divine punishment, suggesting that epidemics were a consequence of collective sin.

The miasma theory, a flawed explanation for disease transmission, dominated thought for centuries, its roots stretching back to antiquity. Understanding its limitations helps us appreciate the complexities of scientific progress; consider the parallel challenge in physics, as highlighted by exploring the fundamental issues with Kaluza-Klein theory, detailed here: what is the problem with the kaluza klein theory.

Just as the miasma theory was eventually superseded, so too might our current understanding of the universe evolve, revealing deeper truths about its fundamental structure.

Finally, the miasma theory’s eventual disproving underscored the limits of human knowledge and the ongoing struggle to understand and control the natural world. These artistic and literary depictions shaped public understanding by reinforcing the belief that disease was a tangible, visible threat emanating from the environment, influencing public health practices and social responses to epidemics.

Fictional Scene Creation

The year is A thick, yellow fog hangs heavy over the narrow, twisting streets of London, clinging to the damp, cobbled alleyways. The air is thick with the stench of rotting refuse, human waste, and the lingering odor of death. Three figures emerge from the gloom: Thomas, a young apprentice, his face pale and drawn; Agnes, a widowed shopkeeper, her eyes red-rimmed and her movements slow; and Master John, a physician, his face partially hidden behind a plague mask, carrying a satchel of herbs and remedies.The setting is a crowded street near the Thames, overflowing with refuse and the dead.

Rats scurry in the shadows. The sounds of coughing and weeping mingle with the distant tolling of church bells. Thomas clutches a handkerchief to his nose, trying to filter out the overpowering stench. Agnes stops to cough, her body wracked with a violent tremor. Master John, despite his mask, grimaces, the stench still assaulting his senses.”The air is foul, Thomas,” Agnes gasps, her voice raspy.

“I feel the sickness coming on again.”Thomas nods, his eyes wide with fear. “It’s everywhere, Mistress Agnes. Even indoors, it’s the same.”Master John approaches them, his gaze assessing their condition. “The miasma is strong tonight,” he states, his voice muffled by the mask. “Stay indoors, keep your windows closed, and burn herbs to purify the air.

May God have mercy on our souls.” The chilling weight of the physician’s words underscores the helplessness in the face of this unseen, yet all-too-present enemy. The fog continues to swirl, a visual manifestation of the miasma, a relentless threat to their lives.

The Concept of “Bad Air” Across Cultures

The association between foul-smelling air and illness is a recurring theme across diverse cultures and historical periods, predating the formal articulation of miasma theory. While the specific explanations varied considerably, a common thread unites these disparate beliefs: the conviction that the quality of the air directly impacted human health and well-being. This intuitive understanding, often rooted in empirical observation, significantly influenced the development and acceptance of the miasma theory in the West.The concept of “bad air” wasn’t simply a matter of unpleasant odors; it encompassed a broader understanding of atmospheric conditions believed to be detrimental to health.

Many cultures identified specific locations or environmental factors—stagnant water, decaying matter, or even specific geographical areas—as sources of noxious air. These beliefs, often intertwined with religious or spiritual explanations of disease, provided a framework for understanding and, to a degree, managing the spread of illness.

Ancient Greek and Roman Views on Bad Air

Ancient Greek and Roman civilizations recognized the relationship between air quality and health, associating foul odors with disease. Hippocrates, considered the “father of medicine,” noted the importance of air, water, and place in health, suggesting that certain environmental factors could predispose individuals to illness. Roman writers and engineers also acknowledged the potential health hazards of poorly ventilated spaces and contaminated water sources.

Their understanding, though lacking the precise biological mechanisms later proposed by miasma theory, laid the groundwork for future investigations. For example, the Romans’ construction of aqueducts and public baths reflected an awareness of the importance of clean water and, by extension, clean air in maintaining public health. This practical approach to environmental hygiene, although not always fully effective, demonstrates a recognition of the connection between environmental factors and health outcomes.

Traditional Chinese Medicine and Environmental Influences

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) also incorporates concepts related to “bad air,” albeit within a different theoretical framework. TCM emphasizes the importance of maintaining a balance of qi (vital energy) and the influence of environmental factors, including air quality, on this balance. Specific environmental conditions were identified as potentially disrupting this balance, leading to illness. While not directly equivalent to the Western miasma theory, the focus on environmental factors and their impact on health demonstrates a parallel recognition of the link between air quality and well-being.

Concepts like wind and dampness, for instance, were seen as potentially pathogenic factors, highlighting the influence of environmental conditions on health in the TCM framework. Practices like the use of incense or specific herbal remedies aimed at purifying the air reflect a similar concern for maintaining a healthy atmosphere.

Indigenous Knowledge Systems and “Bad Air”

Numerous indigenous cultures around the world developed their own understandings of the relationship between air quality and health, often embedded within broader cosmological and spiritual beliefs. These understandings frequently linked specific environmental features—such as swamps, stagnant water, or areas associated with spirits—with disease. The precise nature of these beliefs varied widely across different cultures, but they consistently demonstrated an awareness of the potential health risks associated with certain environmental conditions.

The practical applications of these beliefs often included avoidance of specific areas or the use of traditional remedies to mitigate the perceived negative effects of “bad air.” For instance, some indigenous communities developed sophisticated systems of land management and resource utilization that implicitly acknowledged the importance of environmental health.

User Queries

What specific diseases were commonly attributed to miasma?

Cholera, typhoid fever, and the bubonic plague were among the diseases frequently linked to miasma.

Did anyone ever actively challenge the miasma theory before the germ theory gained traction?

Yes, while the miasma theory dominated for a long time, there were dissenting voices. Some researchers questioned its explanations, even proposing alternative ideas about disease transmission, though these were largely overshadowed.

How did the public react to the implementation of miasma-based public health measures?

Public reactions varied. Some welcomed measures like improved sanitation, while others resisted interventions that impacted their daily lives or perceived as infringements on their freedoms.