What psychological theories is used to diagnose eating disorders? That’s a question that unravels like a particularly delicious, yet ultimately unhealthy, layer cake. We’re not talking about simple calorie counting here; diagnosing these complex conditions requires a nuanced understanding of the mind’s intricate workings. From the unconscious conflicts whispered by psychodynamic theory to the distorted thoughts dissected by cognitive behavioral therapy, and the tangled family dynamics illuminated by family systems theory, the path to diagnosis is a fascinating (and often frustrating) journey through the human psyche.

This exploration will delve into the theoretical frameworks that help clinicians understand and diagnose the spectrum of eating disorders, providing a glimpse into the complexities of these conditions.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) provides the foundational criteria for diagnosing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. However, these criteria are just the starting point. Understanding the underlying psychological mechanisms driving these behaviors requires a deeper dive into various theoretical perspectives. We’ll examine how psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, and family systems theories, among others, contribute to a comprehensive diagnostic assessment.

The process isn’t always straightforward; considerations such as cultural influences, comorbid conditions, and the inherent challenges in self-reporting add layers of complexity to the diagnostic puzzle. We will also touch upon the ethical considerations and the limitations of current diagnostic approaches.

Introduction to Eating Disorder Diagnosis

Diagnosing eating disorders requires a multi-faceted approach, combining clinical interviews, standardized assessments, and a thorough understanding of the individual’s medical and psychological history. The diagnostic process aims to accurately identify the specific eating disorder present, its severity, and any co-occurring conditions that might influence treatment. This understanding is crucial for developing an effective and personalized treatment plan.

DSM-5-TR Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge Eating Disorder

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), provides the standardized criteria for diagnosing eating disorders. These criteria are essential for ensuring consistency and accuracy in diagnosis across different clinicians and settings. Misdiagnosis can lead to ineffective treatment and potentially worsen the individual’s condition.

| Feature | Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge Eating Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Diagnostic Feature | Restriction of energy intake leading to significantly low body weight | Recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors | Recurrent episodes of binge eating without compensatory behaviors |

| Weight | Significantly low weight for age and height | Weight may be within the normal range, overweight, or obese | Weight may be within the normal range, overweight, or obese |

| Body Image | Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight | Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight | Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight |

| Compensatory Behaviors | None specified | Self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; excessive exercise | None |

| Subtypes | Restricting type; Binge-eating/purging type | Purging type; Non-purging type | None |

The Role of Clinical Interviews in Assessing Eating Disorders

Clinical interviews are fundamental in the diagnostic process. They allow clinicians to gather detailed information about the individual’s eating patterns, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The interview process should be sensitive and empathetic, creating a safe space for the individual to share their experiences.Open-ended questions, such as “Can you describe a typical day of eating for you?”, encourage detailed narratives.

Closed-ended questions, like “Do you regularly engage in self-induced vomiting?”, provide specific information. Clinicians might probe for details about the frequency, duration, and context of binge eating episodes, compensatory behaviors, and body image concerns. For example, a clinician might ask about the individual’s feelings before, during, and after binge eating episodes to explore potential triggers and emotional regulation strategies.

The Importance of Considering Comorbid Conditions in Diagnosis

Eating disorders frequently co-occur with other mental health conditions. Recognizing these comorbidities is vital for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning. Ignoring comorbid conditions can lead to incomplete treatment and poorer outcomes.

- Depression and Anxiety: These are extremely common comorbidities, often preceding or following the onset of an eating disorder.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): The rigid control and repetitive behaviors characteristic of OCD can overlap with the restrictive eating patterns and compensatory behaviors seen in eating disorders.

- Substance Use Disorders: Individuals with eating disorders may use substances to cope with emotional distress or to suppress appetite.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Trauma can be a significant factor in the development and maintenance of eating disorders.

The Use of Standardized Assessment Tools in the Diagnosis of Eating Disorders

Standardized assessment tools provide objective measures of eating attitudes, behaviors, and body image. These tools help clinicians quantify the severity of the disorder and monitor progress over time. However, it’s crucial to remember that these tools are not diagnostic in themselves; they supplement clinical judgment.

| Tool | Purpose | Scoring Method |

|---|---|---|

| Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) | Measures attitudes and behaviors related to eating disorders | Summative scoring; higher scores indicate greater eating disorder pathology |

| Bulimia Test (BULIT) | Assesses bulimic symptoms and behaviors | Summative scoring; higher scores indicate greater bulimic pathology |

| Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) | Measures body image concerns and dissatisfaction | Summative scoring; higher scores indicate greater body dissatisfaction |

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)

The DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, is the leading diagnostic manual for mental disorders in the United States and widely used internationally. Its criteria for eating disorders provide a standardized framework for clinicians to assess and diagnose conditions like anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Understanding these criteria is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning.

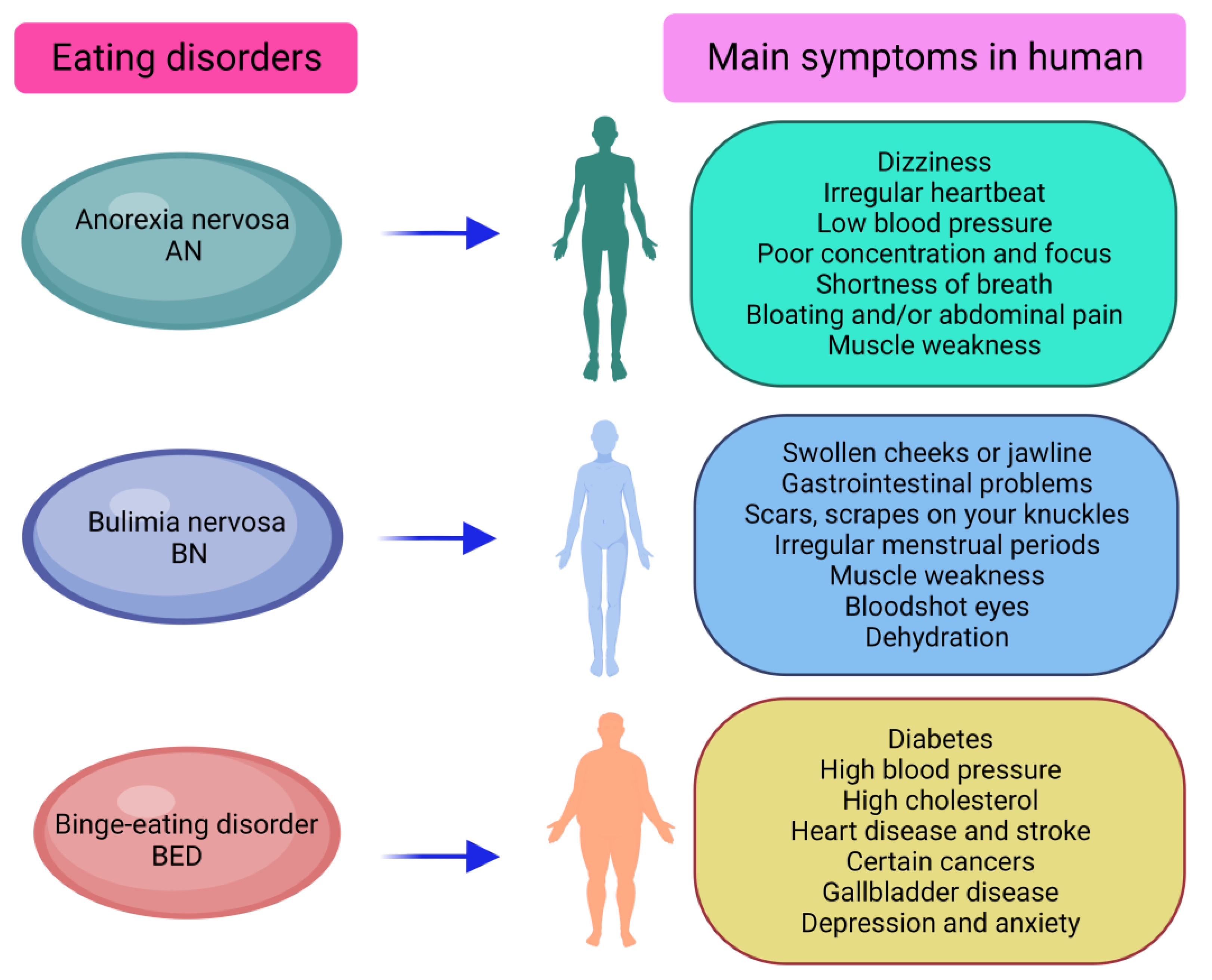

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by a significantly low body weight, intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and a disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced. The DSM-5 Artikels specific criteria for diagnosis, further categorized into subtypes.

Detailed Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa

The DSM-5 Artikels two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: restricting type and binge-eating/purging type. Both subtypes share core features but differ in how individuals maintain their low weight.

- Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. This means the individual consumes far fewer calories than their body needs, resulting in a dangerously low weight. Example: A young woman consistently restricts her food intake to less than 800 calories a day, resulting in a BMI of 15.

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. This fear is pervasive and significantly impacts their daily life. Example: A person avoids social events involving food and engages in excessive exercise to prevent weight gain, despite being severely underweight.

- Disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight. This reflects a distorted body image, where the individual may perceive themselves as overweight even when severely underweight. Example: An individual with a BMI of 14 believes they are still overweight and needs to lose more weight.

Restricting type is characterized by weight loss primarily through dieting, fasting, and/or excessive exercise, while binge-eating/purging type involves recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behavior (self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas).

Severity Specifiers for Anorexia Nervosa

Severity is determined based on Body Mass Index (BMI).

| Severity | BMI (kg/m²) |

|---|---|

| Mild | ≥17 |

| Moderate | 16-16.99 |

| Severe | 15-15.99 |

| Extreme | <15 |

Differential Diagnosis for Anorexia Nervosa

Differentiating anorexia nervosa from other conditions is crucial. It needs to be distinguished from other eating disorders, as well as medical conditions that can cause weight loss (e.g., hyperthyroidism, gastrointestinal disorders, cancer). A thorough medical evaluation is essential to rule out these possibilities.

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain.

Detailed Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances. Example: Consuming a large quantity of food in a short period, feeling a loss of control over eating during the episode.

- Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors in order to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise. These behaviors are employed to counteract the effects of binge eating. Example: Self-induced vomiting after a binge eating episode, using laxatives to prevent weight gain.

- The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. The frequency of these behaviors is a key diagnostic criterion.

- Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight. Body image is a central concern for individuals with bulimia nervosa.

Specificity of Compensatory Behaviors

Compensatory behaviors are diverse and pose significant health risks.

- Self-induced vomiting: Can lead to electrolyte imbalances, tooth decay, and esophageal tears.

- Laxative abuse: Can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and damage to the digestive system.

- Diuretic abuse: Can lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and kidney damage.

- Fasting: Can result in nutritional deficiencies and metabolic disturbances.

- Excessive exercise: Can lead to injuries, exhaustion, and other health problems.

Severity Specifiers for Bulimia Nervosa

Severity is based on the average number of episodes of inappropriate compensatory behaviors per week.

| Severity | Average Number of Episodes of Inappropriate Compensatory Behaviors per Week |

|---|---|

| Mild | 1-3 |

| Moderate | 4-7 |

| Severe | 8-13 |

| Extreme | ≥14 |

Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating without compensatory behaviors.

Detailed Criteria for Binge Eating Disorder

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating. The characteristics of binge eating episodes are the same as described for bulimia nervosa.

- The binge eating episodes are associated with three (or more) of the following: eating much more rapidly than normal; eating until feeling uncomfortably full; eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry; eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating; and feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterward.

- Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. The individual experiences significant emotional distress related to their binge eating.

- The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. The frequency of binge eating is a key diagnostic criterion.

Characteristics of Binge Eating Episodes

Binge eating episodes are characterized by a feeling of loss of control over eating. Individuals may consume large quantities of food rapidly, often feeling unable to stop even when they are uncomfortably full.

Associated Features of Binge Eating Disorder

Commonly associated features include feelings of guilt, shame, and disgust after binge episodes. These negative emotions contribute to a cycle of binge eating and emotional distress.

Comparative Analysis

Table of Diagnostic Criteria

| Criterion | Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge Eating Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly low weight | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Binge eating | May be present (binge-eating/purging type) | Present | Present |

| Compensatory behaviors | May be present (binge-eating/purging type) | Present | Absent |

| Fear of weight gain | Present | Present | May be present |

| Body image disturbance | Present | Present | May be present |

Overlapping Symptoms

While distinct, these disorders share some overlapping symptoms, such as body image concerns and emotional distress. The key differentiating features are the presence or absence of significantly low weight, and the presence or absence of compensatory behaviors.

- Weight: Anorexia nervosa is defined by significantly low weight, unlike bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

- Compensatory Behaviors: Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent compensatory behaviors, which are absent in anorexia nervosa (restricting type) and binge eating disorder.

- Frequency: The frequency of binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors helps differentiate between bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

Additional Considerations

The DSM-5 criteria, while providing a standardized approach, have limitations. Cultural factors can significantly influence the presentation and expression of eating disorders. For example, societal pressures regarding body image can vary across cultures, impacting the prevalence and manifestation of these disorders. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding and diagnostic approaches to eating disorders.

Understanding eating disorders often involves applying theories like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and the psychodynamic approach, examining distorted thoughts and underlying emotional conflicts. Finding the right path to recovery, however, requires holistic care; consider the impact of physical health alongside mental well-being – is it worth investing in a fitness regime like the one described at is orange theory worth it ?

Ultimately, a balanced approach, addressing both psychological and physical aspects, is crucial for successful treatment of eating disorders.

Psychodynamic Theories in Eating Disorder Diagnosis

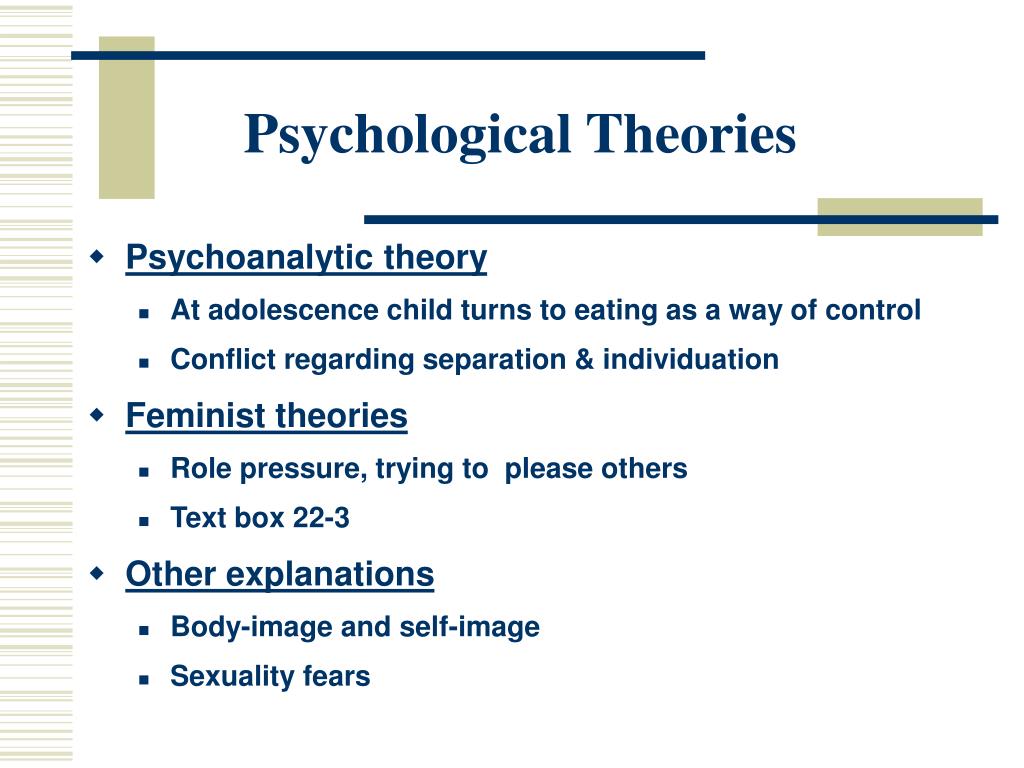

Psychodynamic theory offers a valuable lens through which to understand the complex interplay of unconscious conflicts, early experiences, and relational patterns contributing to the development and maintenance of eating disorders. Unlike purely biological or behavioral approaches, psychodynamic perspectives delve into the individual’s inner world, exploring the psychological roots of disordered eating behaviors. This approach emphasizes the role of unconscious processes, defense mechanisms, and early relationships in shaping an individual’s vulnerability to and experience of these disorders.

Unconscious Conflicts and Defense Mechanisms

Psychodynamic theory posits that eating disorders often stem from unconscious conflicts, particularly those related to control, autonomy, and identity. These conflicts manifest differently across anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED).

Specific Conflicts in Eating Disorders

In anorexia nervosa, the struggle for control often takes center stage. Individuals may use restrictive eating as a means of asserting control over their lives, particularly in situations where they feel powerless or overwhelmed. For example, a young woman facing immense pressure to succeed academically might restrict her food intake as a way to regain a sense of mastery and self-worth.

Bulimia nervosa, conversely, can represent a struggle with impulse control and feelings of inadequacy. Binge eating often follows periods of intense emotional distress, and the subsequent purging (or compensatory behaviors) becomes a desperate attempt to manage overwhelming emotions and self-criticism. A clinical example could be an individual who uses binge eating to cope with feelings of loneliness and isolation, followed by self-induced vomiting to alleviate guilt and anxiety.

In binge eating disorder, the lack of control over eating is paramount. Individuals experience overwhelming urges to consume large quantities of food, often leading to feelings of shame, disgust, and further emotional distress. A person experiencing job loss and financial instability might turn to binge eating as a way to cope with their emotional pain and distress.

Defense Mechanisms in Eating Disorders

Individuals with eating disorders frequently employ defense mechanisms to cope with underlying emotional distress and maintain their disordered eating patterns. Denial, for instance, is common in AN, where individuals may minimize the severity of their weight loss or deny the impact of their behavior on their health. Repression plays a significant role in all three disorders, allowing individuals to push painful emotions and memories into the unconscious.

Projection is evident in the tendency to attribute one’s own feelings of inadequacy or self-hatred onto others. Reaction formation manifests as an exaggerated opposite behavior; for instance, someone with AN might obsessively focus on healthy eating while harboring intense self-loathing.

Table: Defense Mechanisms & Eating Disorder Manifestations

| Defense Mechanism | Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge Eating Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denial | Minimizing weight loss, denying hunger | Ignoring binge-purge cycles | Downplaying the amount of food consumed |

| Repression | Suppressing feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem | Repressing feelings of shame and guilt | Repressing feelings of inadequacy and helplessness |

| Projection | Accusing others of being controlling or critical | Blaming others for triggering binge episodes | Projecting self-criticism onto others |

| Reaction Formation | Obsessively focusing on healthy eating | Engaging in excessive exercise to compensate for binges | Developing strict dietary rules after binges |

| Rationalization | Justifying restrictive eating habits with health concerns | Justifying binge eating as a way to cope with stress | Rationalizing binge eating as a temporary coping mechanism |

Early Childhood Experiences

Psychodynamic theory highlights the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping an individual’s vulnerability to eating disorders. These experiences significantly influence the development of attachment styles and the formation of internal working models of self and others.

Attachment Styles and Eating Disorders

Research suggests a link between insecure attachment styles and the development of eating disorders. Individuals with anxious-ambivalent attachment may be more prone to BN, using food and compensatory behaviors to regulate emotional instability and seek reassurance. Those with avoidant attachment may develop AN, using restriction to control their emotions and maintain distance from others. Disorganized attachment, characterized by unpredictable caregiving, may increase the risk of all three disorders, leading to difficulties in self-regulation and emotional dysregulation.

Family Dynamics and Eating Disorders

Family dynamics, such as enmeshment (excessive closeness and lack of boundaries), over-control (rigid rules and expectations), and emotional neglect (lack of emotional support and validation), can significantly contribute to the development of eating disorders. In families characterized by enmeshment, individuals may struggle to develop a sense of self separate from their family, leading to a reliance on external validation.

Over-controlling families can foster a sense of helplessness and lack of autonomy, potentially triggering restrictive eating as a means of regaining control. Emotional neglect can lead to feelings of emptiness and worthlessness, making individuals more vulnerable to using food to cope with emotional distress.

Trauma and Eating Disorders

Early childhood trauma, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, can play a significant role in the development of eating disorders. From a psychodynamic perspective, trauma can lead to a fragmented sense of self, difficulties regulating emotions, and a reliance on maladaptive coping mechanisms, including disordered eating. The trauma might manifest in eating disorder symptoms as a way to regain a sense of control, numb emotional pain, or express feelings that cannot be verbalized.

Key Psychodynamic Concepts

Several key psychodynamic concepts are crucial in understanding eating disorders.

The Self and Body Image

In eating disorders, the self is often fragmented or poorly developed. Body image disturbances are central to this, reflecting a distorted sense of self and a disconnect between the internal experience and external presentation. The relentless pursuit of thinness becomes a desperate attempt to achieve a sense of control and self-worth, masking underlying feelings of inadequacy and emptiness.

Object Relations and Eating Disorders

Disturbances in object relations—the internalized representations of significant others—play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of eating disorders. Individuals may struggle with unresolved issues of separation-individuation, leading to difficulties establishing healthy boundaries and forming secure attachments. They may also internalize critical or rejecting aspects of their relationships, fueling self-criticism and body image dissatisfaction.

Psychosexual Stages and Eating Disorders

Fixations or regressions at specific psychosexual stages may manifest in eating patterns. For instance, oral fixations may contribute to excessive eating or preoccupation with food, while anal fixations might manifest as rigid control over eating or excessive concern with cleanliness and order.

Countertransference in Eating Disorder Treatment

Therapists working with individuals suffering from eating disorders must be mindful of countertransference—the therapist’s unconscious emotional reactions to the patient. The patient’s struggles with control, body image, and self-worth can trigger strong emotions in the therapist, potentially impacting the therapeutic process. Self-awareness and supervision are essential to manage countertransference effectively.

Therapeutic Interventions

Psychodynamic therapy for eating disorders focuses on exploring unconscious conflicts, working through defense mechanisms, and addressing early childhood experiences. This may involve exploring the patient’s relationship with their body, examining patterns of self-criticism, and addressing relational dynamics. Research suggests that psychodynamic interventions, such as long-term psychotherapy and supportive-expressive therapy, can be effective in improving both eating disorder symptoms and overall psychological well-being.

Case Study: Application of Psychodynamic Theory

[A detailed case study would be included here, illustrating the application of psychodynamic theory to the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with an eating disorder. This would include a description of the patient’s presenting symptoms, relevant developmental history, a psychodynamic interpretation of their eating disorder, and a potential psychodynamic treatment plan. The case study would need to be a fictional example to protect patient confidentiality.]

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Eating Disorders

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely used and effective approach in treating eating disorders. It focuses on the interplay between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, recognizing that these elements are interconnected and influence each other in maintaining the disorder. By targeting these interconnected aspects, CBT aims to help individuals identify and modify maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors associated with their eating disorder.CBT posits that eating disorders are not simply about food or weight, but are maintained by a complex system of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

These elements often reinforce each other, creating a vicious cycle that’s difficult to break without professional intervention. For example, a person with anorexia might engage in restrictive eating (behavior) due to a fear of weight gain (thought) which leads to feelings of control and self-worth (feeling). This positive reinforcement then further strengthens the restrictive eating behavior.

Cognitive Distortions in Eating Disorders

Cognitive distortions are inaccurate or unhelpful ways of thinking that contribute significantly to the development and maintenance of eating disorders. These distorted thought patterns can lead to unrealistic expectations, self-criticism, and rigid rules surrounding food and body image. Common cognitive distortions seen in individuals with eating disorders include all-or-nothing thinking (e.g., “If I eat one cookie, I’ve ruined my diet.”), catastrophizing (e.g., “If I gain weight, I’ll be unlovable.”), and overgeneralization (e.g., “I ate a piece of cake; I’m a failure”).

These distortions fuel the cycle of disordered eating and prevent individuals from adopting healthier eating habits and self-perception.

CBT Techniques for Addressing Maladaptive Thoughts and Behaviors

CBT employs various techniques to help individuals challenge and modify their maladaptive thoughts and behaviors. These techniques aim to break the cycle of distorted thinking and self-defeating actions.One crucial technique is cognitive restructuring, where individuals learn to identify and challenge their negative automatic thoughts. For instance, a therapist might help a person with bulimia identify the thought “I’m worthless if I don’t look perfect” and then examine the evidence supporting and contradicting this belief.

This process helps individuals develop more balanced and realistic perspectives.Behavioral experiments are also commonly used. These involve setting up controlled situations to test out negative predictions. For example, a person with anorexia might be encouraged to eat a small amount of food that they typically avoid and then monitor their anxiety levels. This helps them see that their feared consequences don’t always materialize.Exposure therapy, a form of behavioral therapy often integrated with CBT, is used to help individuals gradually confront feared situations or stimuli.

In the context of eating disorders, this could involve exposure to foods that the person typically avoids or situations that trigger binge eating or purging. Gradual exposure helps reduce avoidance behaviors and associated anxiety.Another important component is relapse prevention planning. This involves identifying potential triggers for relapse and developing coping strategies to manage them. This proactive approach helps individuals maintain their progress and prevent future episodes of disordered eating.

For example, a plan might involve identifying stressful situations that trigger binge eating and developing alternative coping mechanisms like exercise, journaling, or talking to a supportive friend.

Family Systems Theory and Eating Disorders: What Psychological Theories Is Used To Diagnose Eating Disorder

Family systems theory offers a powerful lens through which to understand the development and maintenance of eating disorders. It posits that eating disorders aren’t solely individual problems but are deeply intertwined with the dynamics and patterns of interaction within a family system. By examining family structures, communication styles, and emotional processes, we can gain valuable insights into the contributing factors and develop more effective treatment strategies.

Family Dynamics and Eating Disorder Development

Family dynamics play a significant role in the development of eating disorders. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for effective intervention.

Enmeshment and Differentiation, What psychological theories is used to diagnose eating disorder

Enmeshment, characterized by overly close and indistinct boundaries between family members, and a lack of differentiation, where individuals struggle to maintain a sense of self separate from the family, are frequently observed in families with members suffering from eating disorders. In families with anorexia nervosa, enmeshment might manifest as excessive parental control over the child’s eating, weight, and body image, leaving little room for individual autonomy.

Bulimia nervosa might emerge in families where emotional expression is suppressed, leading to the individual using disordered eating as a coping mechanism for unresolved emotional conflicts. Binge eating disorder could develop in families where there’s a lack of emotional support and individuals use food to regulate their feelings. The blurred boundaries in enmeshed families can make it difficult for the individual to establish a healthy sense of self and independence, contributing to the development of disordered eating patterns.

Rigidity and Chaos

Both rigid and chaotic family structures can contribute to the development and maintenance of eating disorders. Rigid families, characterized by strict rules, inflexible hierarchies, and limited emotional expression, can create an environment where individuals feel stifled and unable to express their needs. This can lead to the development of eating disorders as a way to exert control or express distress.

In contrast, chaotic families, lacking consistent structure and clear boundaries, can also contribute to disordered eating. The lack of stability and predictability can leave individuals feeling insecure and overwhelmed, leading them to seek control through their eating behaviors. For example, a child in a chaotic family might develop anorexia as a way to establish some sense of order and control in their life.

Communication Patterns

Dysfunctional communication patterns are common in families with members experiencing eating disorders. Blaming, where one family member consistently blames another for problems, can create a climate of tension and conflict, exacerbating the individual’s distress and contributing to their disordered eating. Triangulation, where one family member pulls in a third party to mediate a conflict between two others, further complicates communication and prevents direct confrontation of issues.

Double-binds, where an individual receives contradictory messages from different family members, can lead to confusion and anxiety, contributing to the development of eating disorders. For instance, a parent might express concern about their child’s weight while simultaneously praising their thinness, creating a double bind that reinforces disordered eating behaviors.

Parental Influence

Parental modeling, criticism, and control significantly influence the development of eating disorders. Parents who diet frequently or express significant body image concerns may model unhealthy attitudes towards food and weight for their children. Parental criticism, particularly concerning appearance, can damage a child’s self-esteem and body image, increasing their vulnerability to developing an eating disorder. Restrictive eating rules imposed by parents can lead to children developing unhealthy relationships with food and engaging in disordered eating behaviors to regain a sense of control.

Identifying Family Interaction Patterns

Understanding specific family interaction patterns is crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment.

Case Study Analysis

Consider a hypothetical family: The Smiths. Their daughter, Sarah, suffers from anorexia nervosa. The family is highly enmeshed, with Sarah’s parents excessively involved in her life, controlling her every move, including her food intake. Communication is indirect and characterized by avoidance of conflict. The parents express conflicting messages; they worry about Sarah’s weight but also compliment her thinness, creating a double bind.

This combination of enmeshment, indirect communication, and conflicting messages contributes to the maintenance of Sarah’s anorexia.

Table of Family Interaction Patterns

| Family Interaction Pattern | Description | Impact on Anorexia | Impact on Bulimia | Impact on Binge Eating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enmeshment | Overly close, blurred boundaries | Reinforces control, inhibits autonomy | Suppresses emotional expression, leads to compensatory behaviors | Lack of individual identity, reliance on external validation through food |

| Rigid Structure | Strict rules, limited flexibility | Creates a sense of control through restriction | Creates rebellion, leading to secretive binging and purging | Feelings of restriction and lack of control lead to binge eating |

| Chaotic Structure | Lack of consistency, unpredictable environment | Attempts to create order through restrictive eating | Lack of stability, leading to emotional dysregulation and compensatory behaviors | Use of food to cope with anxiety and instability |

| Conflict Avoidance | Suppression of emotions and disagreements | Underlying issues remain unresolved, leading to continued disordered eating | Emotional distress is not addressed, leading to continued cycle of binging and purging | Emotional needs are unmet, leading to continued reliance on food for comfort |

| Overprotective Parenting | Excessive parental control and vigilance | Prevents development of autonomy, reinforces dependence | Prevents healthy emotional development, leads to reliance on unhealthy coping mechanisms | Lack of independence and self-reliance, leads to reliance on external validation through food |

Family Therapy Approaches

Several family therapy approaches are effective in treating eating disorders.

Structural Family Therapy

Structural family therapy focuses on restructuring dysfunctional family hierarchies and boundaries. Therapists work to clarify roles, improve communication, and establish healthier boundaries between family members. In the context of eating disorders, this might involve helping parents to become less controlling while empowering the individual with the eating disorder to take more responsibility for their own health and well-being.

Strategic Family Therapy

Strategic family therapy aims to identify and modify specific problematic family interactions that maintain the eating disorder. Therapists work with families to develop strategies to interrupt negative patterns of communication and behavior, such as challenging the family’s enabling behaviors and reinforcing healthier coping mechanisms. For example, the therapist might work with the family to develop a plan to address conflicts directly and respectfully, rather than avoiding them.

Bowenian Family Therapy

Bowenian family therapy emphasizes increasing the differentiation of self within the family system. This involves helping family members to develop a stronger sense of self and to manage their emotional reactivity within the family context. The therapist helps the family to understand the multigenerational transmission of patterns and to break free from unhealthy relational patterns.

Comparison of Approaches

Structural, strategic, and Bowenian family therapy approaches all aim to improve family dynamics and communication, but they differ in their focus and techniques. Structural therapy emphasizes restructuring family organization, strategic therapy focuses on changing specific behaviors, and Bowenian therapy focuses on improving individual differentiation and reducing emotional reactivity. The most suitable approach depends on the specific family dynamics and the individual’s needs.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations in family therapy for eating disorders include maintaining confidentiality (while balancing the needs of all involved), obtaining informed consent from all family members, and managing potential family conflict. The therapist’s role is crucial in balancing the needs of the individual with the eating disorder and the family, ensuring that everyone feels heard and respected.

Biological Factors and Eating Disorders

Understanding eating disorders requires acknowledging the significant role of biology. Genetic predispositions, neurobiological imbalances, and the medical consequences of disordered eating all contribute to the development and maintenance of these complex conditions. While psychological and environmental factors are crucial, the biological underpinnings cannot be ignored.Genetic factors play a substantial role in increasing susceptibility to eating disorders. Research suggests a heritable component, indicating that individuals with a family history of eating disorders are at a higher risk.

This genetic influence isn’t necessarily about inheriting a specific “eating disorder gene,” but rather inheriting a predisposition towards certain personality traits or biological vulnerabilities that make someone more susceptible to developing an eating disorder when faced with environmental triggers. For example, studies using twin and family studies have consistently shown higher concordance rates for eating disorders in monozygotic (identical) twins compared to dizygotic (fraternal) twins, supporting the role of genetic factors.

Genetic Predisposition and Neurobiological Factors

Genetic variations influence neurotransmitter systems, impacting appetite regulation, mood, and impulse control. These neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, are implicated in the development and maintenance of eating disorders. For instance, imbalances in serotonin, a neurotransmitter crucial for mood regulation and appetite control, have been linked to both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Furthermore, abnormalities in brain regions involved in reward processing and emotional regulation, such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, are often observed in individuals with eating disorders, potentially reflecting both genetic and environmental influences.

Hormonal Imbalances and Eating Behaviors

Hormonal fluctuations can significantly influence appetite, body composition, and mood, all of which are interconnected with eating behaviors. For example, irregularities in leptin, a hormone that signals satiety, can contribute to altered appetite regulation. Individuals with anorexia nervosa often exhibit low leptin levels, which may contribute to their persistent feelings of hunger despite significant weight loss. Similarly, hormonal imbalances associated with puberty or other life stages can exacerbate pre-existing vulnerabilities or trigger the onset of an eating disorder.

The interplay between hormonal fluctuations and psychological stressors can create a complex interplay that significantly impacts eating behaviors.

Medical Complications of Eating Disorders

Severe caloric restriction, purging behaviors (such as self-induced vomiting or laxative abuse), and excessive exercise can lead to a range of serious medical complications. These complications can affect nearly every organ system in the body. For example, anorexia nervosa can cause bradycardia (slow heart rate), hypotension (low blood pressure), and electrolyte imbalances, all of which can be life-threatening.

Bulimia nervosa can lead to dental erosion, esophageal tears, and electrolyte disturbances. These medical consequences underscore the critical need for early intervention and comprehensive treatment that addresses both the psychological and physical aspects of eating disorders. Ignoring the physical manifestations can lead to irreversible damage and, in severe cases, death.

Sociocultural Influences on Eating Disorders

The development and maintenance of eating disorders are rarely solely attributable to individual factors. A significant and often overlooked aspect lies in the pervasive sociocultural pressures that shape our perceptions of body image, ideal weight, and acceptable eating behaviors. These influences permeate our daily lives, subtly yet powerfully impacting individuals’ self-esteem and relationships with food. Understanding these sociocultural forces is crucial for comprehensive prevention and treatment strategies.The relentless bombardment of idealized body images through various media channels significantly contributes to the development and perpetuation of eating disorders.

These images, often digitally altered to present unrealistic standards of thinness, create a skewed perception of what constitutes a “healthy” or “attractive” body. This constant exposure normalizes unhealthy dieting behaviors and fosters body dissatisfaction, particularly among vulnerable individuals. For example, the pervasive use of photo-editing software in magazines and advertising creates a culture where unattainable beauty standards are presented as the norm, leaving many feeling inadequate and pushing them towards extreme measures to conform.

Media Portrayals of Body Image and Eating Disorders

The media’s portrayal of thinness as synonymous with beauty, success, and happiness fuels a cycle of negative self-perception and disordered eating. Television shows, movies, magazines, and social media platforms frequently showcase exceptionally thin individuals, often implicitly or explicitly linking their physical appearance to positive attributes. This constant reinforcement of unrealistic beauty ideals can lead to body dissatisfaction and the adoption of unhealthy weight-control strategies.

Studies have shown a strong correlation between exposure to such media and the increased risk of developing eating disorders, especially among young women. The constant comparison to these unrealistic images can trigger feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem, leading individuals to engage in restrictive dieting, excessive exercise, or purging behaviors in an attempt to achieve the idealized body type.

This relentless pressure to conform to an unattainable standard creates a fertile ground for the development of eating disorders.

Societal Pressures Related to Thinness and Body Weight

Societal pressures surrounding thinness extend beyond media portrayals. The emphasis on thinness as a marker of success, self-discipline, and attractiveness permeates various aspects of life, including the workplace, social interactions, and romantic relationships. This creates a climate where individuals feel immense pressure to conform to societal expectations of body weight and shape, regardless of their individual genetic predispositions or health needs.

The pressure to maintain a certain weight can be particularly intense in professions where appearance is valued, such as modeling, acting, or certain athletic pursuits. This pressure can lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms and the development of eating disorders as individuals strive to meet unrealistic expectations.

Cultural Norms on Eating Habits and Body Image

Cultural norms significantly influence perceptions of body image and eating habits. Different cultures have varying standards of beauty and acceptable body types, which can impact the prevalence and presentation of eating disorders. For example, some cultures may place a higher value on larger body sizes, while others may prioritize thinness. These cultural variations highlight the importance of considering the sociocultural context when diagnosing and treating eating disorders.

The cultural emphasis on certain foods or dietary practices can also influence the development of disordered eating patterns. For instance, cultures that emphasize thinness may lead to restrictive eating habits, while cultures with a strong focus on food as a social event may contribute to overeating or binge eating. Understanding these cultural nuances is crucial for tailoring effective interventions.

The Role of Assessment Tools

Accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of eating disorders rely heavily on comprehensive assessment. This involves utilizing a combination of methods to gather a thorough understanding of the individual’s experiences, behaviors, and overall mental health. A multi-faceted approach ensures a more accurate diagnosis and facilitates the development of a tailored treatment plan.

Standardized Questionnaires in Eating Disorder Assessment

Several standardized questionnaires are valuable tools in the assessment of eating disorders. These instruments offer a structured approach to data collection, allowing for comparison across individuals and tracking of progress over time. However, it’s crucial to remember that questionnaires should be used in conjunction with other assessment methods for a complete picture.

- Eating Disorder Examination (EDE-Q): (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) This questionnaire assesses various aspects of eating disorders in adults, including restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern. It is frequently used across various eating disorder diagnoses. It’s available in several versions, catering to different age groups and diagnostic specificities.

- Bulimia Test (BULIT): (Thelen et al., 1991) This self-report measure specifically targets bulimia nervosa in adults. It evaluates the frequency and severity of binge eating and compensatory behaviors. The BULIT is designed to be relatively brief and easy to administer.

- Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT): (Schwartz et al., 1982) This questionnaire is tailored for assessing eating attitudes and behaviors in children and adolescents. It is sensitive to various eating disorder symptoms and can help identify individuals at risk. The ChEAT is particularly useful in detecting early signs of developing eating disorders.

Conducting a Clinical Interview for Eating Disorder Assessment

The clinical interview is a cornerstone of eating disorder assessment. It allows for a nuanced understanding of the individual’s unique experience, going beyond the quantitative data provided by questionnaires. The process involves several key steps:

- Establishing Rapport: Creating a safe and trusting environment is paramount. This involves active listening, empathy, and demonstrating genuine concern for the patient’s well-being.

- Comprehensive History: Gathering a detailed history is crucial, encompassing medical history (including any past or current physical health concerns), psychiatric history (previous diagnoses, treatments, hospitalizations), social history (relationships, social support, life stressors), and family history (family history of eating disorders or other mental health conditions).

- Mental Status Examination: This assesses the patient’s current cognitive functioning, mood, affect, thought processes, and overall psychological state.

- Specific Questioning Techniques: This involves targeted questions to explore eating disorder symptoms, such as the frequency and nature of binge eating episodes, compensatory behaviors (purging, excessive exercise, fasting), body image concerns, and the impact of these behaviors on their life.

- Confidentiality and Ethical Considerations: Maintaining patient confidentiality is crucial. This includes adhering to relevant ethical guidelines, ensuring informed consent, and protecting the patient’s privacy.

Comparison of Different Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Description (including target population and specific eating disorder focus) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) | Structured clinical interview assessing various aspects of eating disorders in adults; broad applicability across diagnoses. | High reliability and validity; detailed information; clinician-administered. | Time-consuming; requires trained clinicians; potential for interviewer bias. |

| EDE-Q | Self-report questionnaire assessing similar aspects to the EDE; suitable for adults and adolescents; various versions available. | Efficient; allows for self-monitoring; readily available. | Subject to response bias; may not capture the full complexity of the disorder. |

| Bulimia Test (BULIT) | Self-report questionnaire specifically for bulimia nervosa in adults. | Brief and easy to administer; specific focus on bulimic symptoms. | Limited scope; may not be suitable for other eating disorders. |

| Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT) | Self-report questionnaire for children and adolescents; assesses eating attitudes and behaviors. | Age-appropriate; identifies at-risk individuals. | May not be suitable for adults; potential for misunderstanding questions. |

| Clinical Interview | Structured or semi-structured interview focusing on the individual’s history and current experience; adaptable to various ages and presentations. | Allows for in-depth exploration; builds rapport; contextualizes findings. | Time-consuming; relies on clinician’s skill and experience; potential for bias. |

The selection of tools depends on factors such as patient age, presenting symptoms, available resources, and clinician expertise. The tools included represent a range of options from self-report questionnaires to clinical interviews, reflecting best practice in a comprehensive assessment.

Limitations of Relying Solely on Self-Report Measures

Self-report measures, while convenient and efficient, are subject to limitations. Individuals with eating disorders may underreport or distort information due to denial, shame, or a desire to present themselves in a more positive light. This can lead to inaccurate assessments and hinder the development of effective treatment plans. Therefore, self-report data should always be interpreted cautiously and corroborated with other assessment methods.

Decision-Making Process for Selecting Assessment Tools

A flowchart would visually represent the decision-making process, starting with initial patient presentation and progressing through a series of questions regarding age, presenting symptoms, and available resources. The flow would ultimately lead to a selection of appropriate assessment tools. (Note: A visual flowchart is not included here due to limitations in text-based response generation). The flowchart would need to consider factors such as the patient’s age (child, adolescent, adult), presenting symptoms (e.g., restrictive eating, binge eating, purging), the clinician’s expertise, time constraints, and the availability of resources (e.g., access to specialized testing, time for lengthy interviews).

Case Study Illustrating Assessment Tool Application

Sarah, a 20-year-old college student, presented with concerns about weight and body image. The EDE-Q revealed high scores on restraint and shape concern, suggesting restrictive eating patterns and significant body image distress. A subsequent clinical interview revealed a history of dieting, episodes of binge eating, and self-induced vomiting. The combination of the EDE-Q and the clinical interview strongly suggested a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa.

This informed the treatment plan, which included CBT-E (Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) to address her distorted cognitions and maladaptive behaviors.

Resources for Further Information on Eating Disorder Assessment

- Fairburn, C. G., & Cooper, Z. (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination: A semi-structured interview for the assessment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 14*(1), 1-8. This article details the development and validation of the EDE.

- Thelen, M. H., Wonderlich, S. A., & Johnson, C. (1991). The bulimia test (BULIT): Development and validation of a short self-report measure.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47*(6), 842-850.* This article describes the BULIT and its psychometric properties.

- Schwartz, M. B., Thompson, M. K., & Johnson, C. (1982). The children’s eating attitudes test: A measure of eating disturbances in children.

Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 11*(4), 355-364.* This article introduces the ChEAT and its application in younger populations.

- National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). (n.d.). National Eating Disorders Association.* Retrieved from [Insert NEDA website address here]. NEDA provides comprehensive information on eating disorders, including assessment and treatment.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013).Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders* (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. The DSM-5 provides diagnostic criteria for eating disorders.

Differentiating Eating Disorders from Other Conditions

Accurately diagnosing eating disorders requires careful consideration of other conditions that may share similar symptoms. Overlapping symptoms can lead to misdiagnosis, delaying appropriate treatment and potentially worsening the patient’s condition. This section delves into the differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, comparing them with various medical and psychological conditions.

Anorexia Nervosa Differential Diagnosis

Anorexia nervosa often presents with symptoms that mimic other conditions, making differential diagnosis crucial. Weight loss, fatigue, and social withdrawal, for instance, are common in both anorexia nervosa and depressive disorders. Similarly, obsessive thoughts about food and body image are shared with anxiety disorders. Differentiating these conditions requires a thorough assessment of diagnostic criteria and clinical presentation.

Anorexia Nervosa vs. Depressive Disorders

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and persistent depressive disorder (PDD) can share symptoms like weight loss, fatigue, and social withdrawal with anorexia nervosa. However, the core diagnostic criteria differ significantly. Anorexia nervosa is characterized by a distorted body image and intense fear of gaining weight, leading to restrictive eating behaviors. In contrast, MDD and PDD involve persistent sadness, loss of interest, and changes in appetite or sleep, without the same emphasis on body image distortion and weight control.

| Criterion | Anorexia Nervosa | Major Depressive Disorder | Persistent Depressive Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Loss | Significant weight loss, below 85% of expected weight | May involve weight loss or gain, but not central to diagnosis | May involve weight loss or gain, but not central to diagnosis |

| Body Image | Distorted body image, intense fear of gaining weight | Not a primary feature | Not a primary feature |

| Eating Behaviors | Restrictive eating, often accompanied by compensatory behaviors | Changes in appetite, but not necessarily restrictive | Changes in appetite, but not necessarily restrictive |

| Mood | May present with irritability or anxiety, but not necessarily persistent sadness | Persistent sadness, loss of interest, feelings of hopelessness | Persistent low mood, lasting at least two years |

Anorexia Nervosa vs. Anxiety Disorders

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can share features with anorexia nervosa, particularly the obsessive thoughts and rituals related to food and body image. Individuals with anorexia nervosa may exhibit obsessive thoughts about food intake, calorie counting, and body shape. Similarly, individuals with OCD might engage in repetitive behaviors related to food or exercise. However, the focus in anorexia nervosa is primarily on weight control and body image, whereas in GAD and OCD, the obsessions and compulsions are broader and not solely focused on food and weight.

Management differs significantly; anorexia nervosa treatment addresses the underlying eating disorder, while GAD and OCD treatment focuses on managing anxiety and compulsions through techniques like exposure and response prevention.

Anorexia Nervosa vs. Gastrointestinal Disorders & Medical Conditions

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can present with weight loss and altered bowel habits, potentially mimicking anorexia nervosa. However, these conditions are characterized by specific gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel movements. Hyperthyroidism and diabetes can also cause unintentional weight loss, but these are diagnosed through blood tests and other medical investigations, revealing underlying hormonal imbalances or metabolic issues.

A diagnostic flowchart would systematically assess for these conditions, starting with a comprehensive physical examination and blood tests to rule out medical causes before focusing on psychological factors. For example, thyroid function tests would be used to rule out hyperthyroidism. Similarly, fasting blood glucose tests would help in diagnosing diabetes.

The Importance of a Multidisciplinary Approach

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/VWH_Illustration_Diagnosis-of-Eating-Disorders_Illustrator_Theresa-Chiechi_Final-23f3b27f6efb4be2944143b142ee6922.jpg)

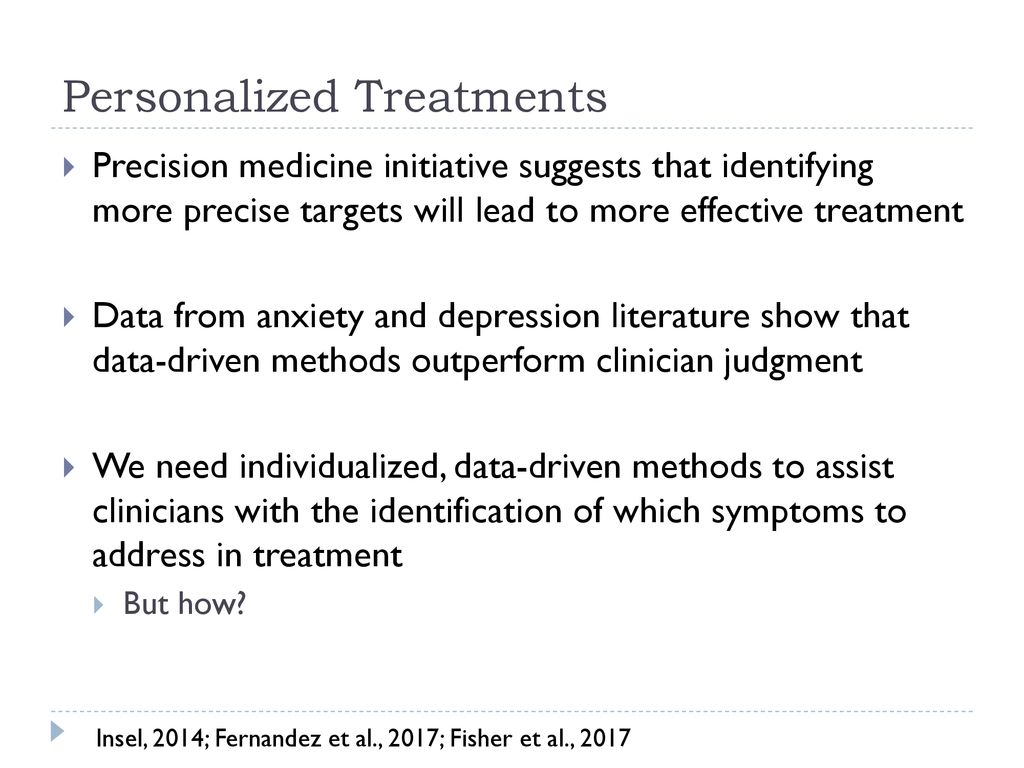

Effective eating disorder treatment hinges on a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach. Unlike single-discipline interventions, this model leverages the expertise of various healthcare professionals, resulting in significantly improved patient outcomes, reduced treatment duration, and a lower relapse rate. This holistic strategy addresses the multifaceted nature of eating disorders, encompassing biological, psychological, and social factors.

Benefits of Coordinated Care in Eating Disorder Treatment

A meta-analysis of studies comparing multidisciplinary to single-discipline approaches revealed a statistically significant improvement in weight restoration and symptom reduction in patients with anorexia nervosa treated with multidisciplinary care (Herpertz-Dahlmann et al., 2017). Furthermore, studies have shown that coordinated care can reduce treatment duration by up to 30% and significantly decrease the risk of relapse within the first year post-treatment, though precise figures vary depending on the specific eating disorder and the intensity of the intervention (Couturier et al., 2013).

This improvement is largely attributed to the shared decision-making process, which minimizes conflicting treatment plans and fosters a consistent therapeutic environment. The shared understanding of the patient’s needs across professionals prevents contradictory advice and ensures a more effective and supportive journey.

Understanding eating disorders often involves applying theories like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and the biopsychosocial model, examining the interplay of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Sometimes, finding solutions requires a strategic approach, much like solving complex equations; learning how to solve game theory problems with fmincon in matlab can illustrate the power of systematic problem-solving. This same methodical approach can be invaluable in unraveling the intricate dynamics of an eating disorder, paving the way for effective treatment and recovery.

Roles of Different Professionals in Eating Disorder Care

- Psychiatrist: Provides medication management, addresses co-occurring psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety), and monitors overall mental health status. They may prescribe antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, or other psychotropics to alleviate symptoms.

- Psychologist: Conducts individual and/or group therapy, focusing on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), or other evidence-based approaches to address underlying psychological factors contributing to the eating disorder. They help patients identify and challenge maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

- Registered Dietitian/Nutritionist: Develops and monitors individualized meal plans, educates patients about nutrition, and helps restore healthy eating patterns. They work closely with the patient to address nutritional deficiencies and establish a positive relationship with food.

- Medical Doctor: Monitors physical health, addresses medical complications (e.g., electrolyte imbalances, cardiac issues), and conducts regular physical examinations. They may order blood tests, electrocardiograms (ECGs), or other diagnostic tests to assess the patient’s overall physical condition.

- Occupational Therapist: Helps patients regain functional skills impacted by the eating disorder, such as improving self-care routines and managing daily activities. They might focus on improving physical endurance and coping skills.

- Social Worker: Addresses social and environmental factors that contribute to the eating disorder, provides support to the patient and family, and connects them with community resources. They help patients navigate social challenges and build support systems.

These roles intersect frequently; for example, the dietitian might inform the psychologist about the patient’s progress with meal plans, influencing the content of therapy sessions. The psychiatrist might adjust medication based on feedback from the psychologist or medical doctor regarding the patient’s overall mental and physical state.

Flowchart Illustrating a Multidisciplinary Approach to Eating Disorder Care

A flowchart would visually represent the process starting with initial assessment by a primary care physician or therapist, followed by a referral to a multidisciplinary team. Subsequent steps would include comprehensive assessments by each professional (psychiatrist, psychologist, dietitian, medical doctor), collaborative treatment planning, ongoing monitoring with regular meetings of the team, and adjustments to the treatment plan based on progress.

Decision points would include evaluating treatment response, managing medical complications, and addressing potential relapse. Referral pathways would be shown for specialized services as needed (e.g., inpatient hospitalization). Interactions between team members are highlighted at each stage, such as joint treatment planning meetings and shared progress updates.

Comparison of Treatment Approaches for Anorexia Nervosa

| Professional | Primary Treatment Modality | Frequency of Sessions | Typical Duration of Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrist | Medication management, psychiatric evaluation | 1-4 per month | Variable, depending on needs |

| Psychologist | CBT, DBT, psychodynamic therapy | 1-2 per week | 6 months to 1 year or longer |

| Registered Dietitian | Nutritional counseling, meal planning | 1-2 per week initially, tapering off | 6 months to 1 year or longer |

| Medical Doctor | Medical monitoring, management of physical complications | As needed, potentially monthly | Variable, depending on needs |

Case Study: Multidisciplinary Approach to Bulimia Nervosa

Sarah, a 24-year-old woman, presented with symptoms of bulimia nervosa, including binge eating and purging behaviors, low self-esteem, and depression. A multidisciplinary team, including a psychiatrist, psychologist, and dietitian, was assembled. The psychiatrist prescribed an antidepressant to address her depression and anxiety. The psychologist implemented CBT to help Sarah identify and challenge her negative thoughts and behaviors related to food and body image.

The dietitian developed a meal plan to address nutritional deficiencies and promote regular, healthy eating habits. Through collaborative efforts, regular monitoring, and adjustments to the treatment plan, Sarah showed significant improvement in her binge-purge cycles, mood, and self-esteem after six months of treatment.

Challenges in Coordinating Multidisciplinary Care and Proposed Solutions

- Challenge: Scheduling conflicts between professionals with busy schedules. Solution: Implement a centralized scheduling system and prioritize joint appointments where possible.

- Challenge: Communication barriers between team members using different communication methods. Solution: Utilize a shared electronic health record (EHR) system and establish regular team meetings.

- Challenge: Differing treatment philosophies among team members. Solution: Establish clear treatment goals and protocols at the outset, emphasizing evidence-based practices.

- Challenge: Limited access to specialized services (e.g., DBT therapists) in certain geographical areas. Solution: Explore telehealth options and collaborate with professionals in other locations.

- Challenge: High cost of multidisciplinary care, potentially impacting patient access. Solution: Advocate for insurance coverage and explore financial assistance programs.

Ethical Considerations in Diagnosis

Accurately diagnosing eating disorders requires a nuanced understanding of ethical principles. The process is not merely about applying diagnostic criteria; it involves navigating complex issues of patient autonomy, cultural sensitivity, and the potential for misdiagnosis, all while upholding the highest standards of professional conduct. Failure to consider these ethical dimensions can lead to ineffective treatment and even harm to the individual.The assessment and diagnosis of eating disorders necessitate careful consideration of several key ethical principles.

These principles ensure that the diagnostic process is fair, respectful, and ultimately beneficial for the patient.

Cultural Sensitivity in Eating Disorder Diagnosis

Cultural factors significantly influence the presentation and experience of eating disorders. Diagnostic criteria, developed largely within Western contexts, may not adequately capture the diverse manifestations of these conditions across different cultures. For example, certain cultures may emphasize different body ideals, leading to variations in the types of eating disorders observed and the ways they are expressed. Clinicians must be aware of these cultural nuances to avoid misinterpreting symptoms and making inaccurate diagnoses.

This requires ongoing education and a commitment to culturally competent practice, including seeking consultation from individuals with expertise in relevant cultural contexts when needed. A failure to account for cultural differences could lead to stigmatization and inadequate treatment.

Informed Consent in Eating Disorder Assessment and Treatment

Informed consent is paramount in all aspects of healthcare, and the assessment and treatment of eating disorders are no exception. Patients must be fully informed about the diagnostic process, including the methods used, the potential risks and benefits, and the implications of a diagnosis. This includes providing clear explanations of the diagnostic criteria, the limitations of diagnostic tools, and the possible courses of treatment.

Patients should also be made aware of their right to refuse any aspect of the assessment or treatment, and their decision should be respected. Obtaining truly informed consent requires establishing a trusting therapeutic relationship based on open communication and mutual respect. A lack of informed consent can undermine the therapeutic alliance and lead to distrust and treatment non-compliance.

Confidentiality and Privacy in Eating Disorder Care

Maintaining confidentiality and respecting patient privacy are essential ethical considerations. Information gathered during the assessment and treatment process must be protected and disclosed only with the patient’s consent, except in situations where mandated reporting is required (e.g., situations involving imminent danger to self or others). Clinicians must adhere to relevant professional guidelines and legal regulations regarding confidentiality. Breaches of confidentiality can severely damage the therapeutic relationship and erode trust.

Strict adherence to privacy protocols is crucial in ensuring the safety and well-being of individuals seeking help for eating disorders.

Challenges in Diagnosing Eating Disorders

Diagnosing eating disorders presents significant challenges due to the multifaceted nature of these conditions and the variability in their presentation. Accurate diagnosis requires a comprehensive understanding of the diagnostic criteria, a nuanced appreciation of individual differences, and a keen awareness of potential confounding factors. Overcoming these hurdles is crucial for ensuring timely and effective intervention.The complexities inherent in diagnosing eating disorders stem from several key factors.

These disorders often co-occur with other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, making differential diagnosis challenging. Furthermore, individuals with eating disorders may not always openly disclose their symptoms, leading to underreporting and delayed diagnosis. The subjective nature of some diagnostic criteria, such as body image distortion, adds another layer of complexity.

Diagnostic Criteria Ambiguity and Overlap with Other Conditions

The DSM-5 criteria, while comprehensive, can be difficult to apply consistently in practice. The overlap in symptoms between different eating disorders, and between eating disorders and other mental health conditions, frequently leads to diagnostic uncertainty. For example, restrictive eating patterns can be present in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), making differentiation challenging. Similarly, symptoms of anxiety and depression are common in individuals with eating disorders, making it difficult to determine whether these are primary or secondary conditions.

This necessitates a thorough clinical assessment to identify the core features of the eating disorder and rule out other conditions. Clinicians often rely on detailed interviews, behavioral observations, and psychological testing to differentiate between diagnoses.

Diagnostic Challenges in Diverse Populations

Diagnosing eating disorders in diverse populations presents unique challenges. Cultural norms and beliefs surrounding body image and food intake can significantly influence the presentation of symptoms and complicate diagnosis. For example, cultural expectations of thinness may mask or exacerbate eating disorder symptoms in some populations. Furthermore, language barriers, cultural stigma, and lack of culturally appropriate assessment tools can hinder accurate diagnosis in individuals from diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds.

Addressing these challenges requires culturally sensitive assessment strategies, including the use of interpreters and culturally adapted assessment tools. Clinicians must also be aware of cultural variations in eating habits and body image ideals to avoid misinterpreting symptoms.

Strategies for Overcoming Diagnostic Challenges

Overcoming the challenges in diagnosing eating disorders requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes employing standardized assessment tools, conducting thorough clinical interviews, and utilizing a multidisciplinary team approach. Standardized assessment tools, such as the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) and the SCOFF questionnaire, provide structured methods for assessing eating disorder symptoms and behaviors. Thorough clinical interviews allow clinicians to gather comprehensive information about the individual’s history, current symptoms, and psychosocial context.

A multidisciplinary team approach, involving psychiatrists, psychologists, registered dietitians, and other healthcare professionals, can offer a holistic perspective and enhance the accuracy of diagnosis. Furthermore, ongoing training and education for clinicians on the latest diagnostic criteria and culturally sensitive assessment strategies are crucial to improve diagnostic accuracy and ensure equitable access to care for all individuals.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

The understanding and treatment of eating disorders are constantly evolving, driven by advancements in neuroscience, genetics, and technology. New research is shedding light on the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors contributing to these disorders, paving the way for more effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions. This ongoing evolution is crucial for improving the lives of individuals struggling with these debilitating conditions.Emerging research is exploring the intricate biological mechanisms underlying eating disorders.

For instance, studies are investigating the role of specific genes and their interactions with environmental factors in predisposing individuals to anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Advances in neuroimaging techniques are allowing researchers to visualize brain activity in individuals with eating disorders, providing insights into the neural pathways involved in appetite regulation, emotional processing, and body image perception.

These findings are leading to a more nuanced understanding of the disorder’s etiology and potential targets for treatment.

Neurobiological Mechanisms and Treatment Targets

Research is increasingly focusing on the neurobiological underpinnings of eating disorders. Studies are exploring the roles of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and neuropeptide Y in regulating appetite, mood, and impulsivity. Disruptions in these neurotransmitter systems are believed to contribute to the disordered eating behaviors characteristic of these conditions. This research is informing the development of novel pharmacological interventions targeting specific neurobiological pathways.

For example, studies are investigating the efficacy of medications that modulate serotonin levels in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Further research into the complex interplay of these neurotransmitters promises to lead to more effective and personalized treatments.

The Potential of New Diagnostic Tools and Technologies

Technological advancements are offering new possibilities for the diagnosis and monitoring of eating disorders. For example, the use of wearable sensors to track activity levels, sleep patterns, and dietary intake can provide objective data to supplement clinical assessments. Digital phenotyping, which involves the use of smartphone apps and other digital technologies to collect data on behavior and symptoms, holds promise for early detection and personalized treatment.

Furthermore, advancements in neuroimaging, such as fMRI and EEG, are enabling researchers to identify specific brain patterns associated with eating disorders, potentially leading to more accurate and earlier diagnosis. Imagine a future where a simple brain scan could help identify individuals at high risk for developing an eating disorder, allowing for early intervention and prevention strategies.

Areas for Future Research in Eating Disorder Diagnosis

The complexity of eating disorders necessitates continued research across multiple domains. Several areas warrant particular attention:

- Developing more sensitive and specific biomarkers for early detection of eating disorders.

- Investigating the long-term effects of early intervention programs on preventing relapse and improving overall outcomes.

- Exploring the effectiveness of different therapeutic approaches for diverse subtypes of eating disorders and considering cultural factors.

- Improving the accuracy and efficiency of diagnostic tools to minimize misdiagnosis and delays in treatment.

- Conducting longitudinal studies to track the development and progression of eating disorders across the lifespan.

Query Resolution

What is the role of a dietitian in diagnosing an eating disorder?

While dietitians don’t diagnose, they play a crucial role in assessing nutritional status, identifying dietary restrictions or patterns, and collaborating with the treatment team to develop a healthy eating plan.

Can someone be diagnosed with more than one eating disorder?

Yes, comorbidity is common. Individuals may meet criteria for multiple eating disorders simultaneously or experience a shift in diagnoses over time.

How long does it typically take to get a diagnosis?

This varies greatly depending on the individual’s situation, access to care, and the complexity of their case. It can range from a few weeks to several months.

Are there biological tests to diagnose eating disorders?

No single biological test exists. Blood tests and other medical assessments are used to rule out other medical conditions that might mimic eating disorder symptoms.

What if my doctor doesn’t believe my symptoms?

Seek a second opinion. It’s crucial to find a healthcare professional who understands and validates your experience.