What is the one primary issue with equity theory? The seemingly straightforward answer – inequity – belies a complex web of individual perceptions, cultural norms, and organizational structures. Equity theory, while offering valuable insights into motivation and fairness, ultimately stumbles on the subjective nature of perceived fairness. This inherent subjectivity leads to inconsistencies in how individuals react to perceived inequities, rendering the theory’s predictive power limited and its practical application challenging.

This critical review delves into the core issue, exploring the nuances of inequity and its far-reaching consequences.

The central problem lies in the difficulty of objectively measuring “fairness.” Equity theory posits that individuals compare their input-output ratios to those of others. However, what constitutes “fair” input and “fair” output is highly personal and influenced by factors ranging from individual values and past experiences to cultural norms and organizational context. This makes consistent and accurate prediction of behavior based solely on perceived equity incredibly difficult.

Furthermore, the theory struggles to account for individual differences in tolerance for inequity and the various coping mechanisms employed when faced with perceived unfairness, such as cognitive distortion or acceptance. The following analysis will dissect these complexities, highlighting the limitations of the theory while acknowledging its significant contributions to our understanding of workplace motivation.

Defining Equity Theory

Equity theory, at its core, is all about perceived fairness in social exchanges. It suggests that individuals are motivated to maintain a balance between what they put into a relationship or situation (inputs) and what they get out of it (outputs), compared to what others receive. Feeling this balance is disrupted—that there’s inequity—can significantly impact motivation and behavior.

Core Principles of Equity Theory

The central concept is the perceived ratio of inputs to outputs. Individuals compare their own input/output ratio to that of a “comparison other,” someone they perceive as relevant. If the ratios are perceived as equal, a state of equity exists, leading to satisfaction and continued engagement. However, if the ratios are perceived as unequal, inequity arises, causing tension and potentially prompting actions to restore balance.

This feeling of inequity is a powerful motivator, pushing individuals to act in ways that reduce the perceived imbalance.

Components of Equity Theory

Equity theory rests on three key components: inputs, outputs, and comparison others.

- Inputs: These are the contributions an individual makes to a situation. Examples include:

- Effort: Working overtime, dedicating extra time to a project, consistently exceeding expectations.

- Skills: Possessing specialized knowledge, expertise, or proficiency in a particular area; a highly skilled surgeon, for instance, possesses skills that are in high demand.

- Experience: Years of service, accumulated knowledge and expertise gained over time, a seasoned manager with years of experience in the industry.

- Outputs: These are the rewards or benefits an individual receives. Examples include:

- Salary: The monetary compensation received for work performed; a high-paying job versus a minimum wage job.

- Recognition: Awards, promotions, public acknowledgment of achievements; employee of the month award, a promotion to a higher position, receiving a significant bonus.

- Responsibility: Level of autonomy, decision-making power, scope of influence; managing a large team versus working as an individual contributor.

- Comparison Other: This is the individual to whom a person compares their input/output ratio. The choice of comparison other can be influenced by factors such as similarity, proximity, and social status. Examples include:

- Coworker: Comparing your salary and responsibilities to a colleague with similar experience.

- Friend: Comparing your relationship satisfaction to that of a close friend’s relationship.

- Sibling: Comparing the level of parental attention and support received in childhood.

The interaction of these components determines feelings of equity or inequity. For instance, if an individual perceives that their inputs (effort, skills) are significantly greater than their outputs (salary, recognition) compared to a coworker (comparison other), they will likely feel under-rewarded and experience inequity.

Examples of Equity Theory in Action

The following table illustrates equity theory across different contexts:

| Example Context | Inputs | Outputs | Comparison Other | Perceived Equity/Inequity | Behavioral Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace | High effort, advanced skills, long hours | Low salary, limited recognition, little responsibility | Coworker with similar inputs but higher outputs | Inequity (under-rewarded) | Reduced effort, job search |

| Relationship | Emotional support, time commitment, financial contributions | Limited affection, infrequent communication, unequal sharing of household chores | Friend’s relationship with equal contributions and reciprocal benefits | Inequity (under-rewarded) | Withdrawal, decreased commitment |

| Volunteer Work | Significant time commitment, specialized skills, fundraising efforts | Minimal appreciation, limited opportunities for skill development, lack of recognition | Fellow volunteer with similar inputs but greater recognition | Inequity (under-rewarded) | Reduced participation, decreased motivation |

Equity Theory vs. Expectancy Theory

Equity theory and expectancy theory are both motivational theories, but they differ in their core assumptions and focus.

- Equity Theory: Focuses on social comparison and perceived fairness of rewards relative to others’ rewards; driven by a desire for justice and equity.

- Expectancy Theory: Focuses on individual beliefs about effort-performance relationships, performance-outcome relationships, and the value of outcomes; driven by a desire for personal gain and maximizing rewards.

- Underlying Assumptions: Equity theory assumes individuals are motivated to maintain fairness; expectancy theory assumes individuals are motivated by maximizing their personal outcomes.

- Motivational Drivers: Equity theory emphasizes fairness and justice; expectancy theory emphasizes individual beliefs and expectations.

- Situational Applicability: Equity theory is most applicable in situations involving social comparisons and interpersonal interactions; expectancy theory is most applicable in situations where individual effort and performance can be clearly linked to outcomes.

Equity Theory and Organizational Behavior

Equity theory has significant implications for organizational justice and employee motivation. Organizations can use equity theory to create fair compensation systems, ensuring that pay and benefits are perceived as equitable across employees. This can boost morale and reduce turnover. Strategies for managing perceived inequity include transparent communication about compensation decisions, providing opportunities for employee input, and ensuring consistent application of performance evaluation criteria.Understanding equity theory is vital for improving job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Research supports the idea that perceived inequity leads to decreased job satisfaction and commitment (Adams, 1965; Huseman, Hatfield, & Miles, 1987).

Limitations of Equity Theory

Equity theory, while insightful, has limitations:

- Subjectivity of Perceptions: Individuals’ perceptions of inputs and outputs, and the choice of comparison others, are subjective and can be influenced by biases.

- Difficulty in Measurement: Accurately measuring inputs and outputs, particularly intangible ones like effort and recognition, is challenging.

- Individual Differences: People differ in their tolerance for inequity; some are more sensitive to perceived unfairness than others.

- Cultural Variations: The importance of equity and the ways in which inequity is addressed can vary across cultures.

Equity Theory Applications Beyond the Workplace

Equity theory applies to various settings beyond the workplace:

- Interpersonal Relationships: A couple might experience inequity if one partner consistently contributes more time and effort to household chores than the other. Another example might be an unequal distribution of childcare responsibilities between parents, leading to resentment and conflict.

- Family Dynamics: Siblings might perceive inequity if one receives more attention or resources from parents than the other. Another example could be an unequal distribution of inheritance amongst siblings.

- Volunteer Settings: Volunteers might feel under-rewarded if they contribute significantly more time and effort than others but receive less recognition or appreciation. Another example could be an unequal distribution of tasks amongst volunteers, leading to some feeling overburdened.

Identifying the Primary Issue

So, we’ve established what equity theory is all about – fairness in the workplace, or really any exchange relationship. But like any theory, it has its limitations. The core problem with equity theory boils down to one thing: inequity. It’s the very thing the theory aims to avoid, yet it’s also the engine driving its predictions.The concept of inequity is pretty straightforward: it’s the feeling of unfairness that arises when we perceive a disparity between our inputs (effort, skills, experience) and outcomes (pay, recognition, promotion) relative to someone else.

This comparison is key; it’s not just about our own satisfaction, but how we stack up against others we perceive as similar. This subjective comparison is what makes the theory so interesting and, sometimes, a little messy.

Types of Inequity

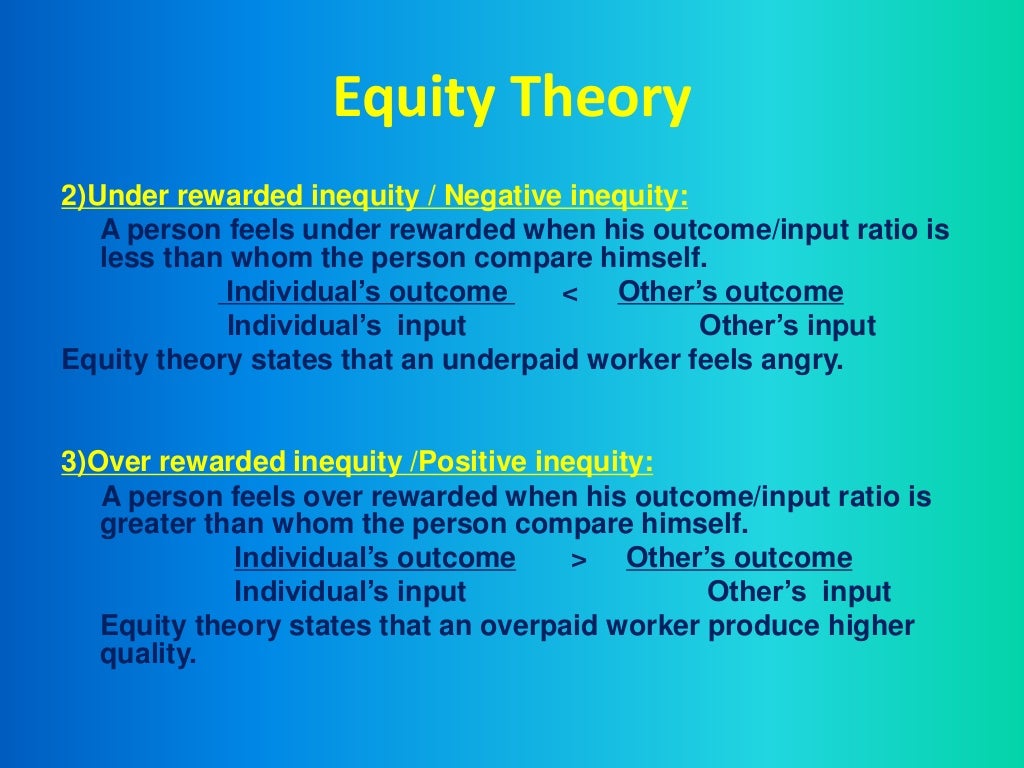

Inequity manifests in two primary ways: underpayment inequity and overpayment inequity. Underpayment inequity happens when we feel we’re putting in more than we’re getting out, compared to a referent other. Conversely, overpayment inequity occurs when we perceive we’re receiving more than we deserve relative to our inputs compared to a referent other. Both situations create tension and can lead to various behavioral adjustments to restore a sense of balance.

Underpayment Inequity Examples

Imagine Sarah, a software engineer, who consistently works late nights and weekends to meet deadlines. She’s highly skilled and contributes significantly to her team’s success. However, she discovers that her colleague, Mark, with similar experience and less dedication, earns a substantially higher salary. This creates underpayment inequity for Sarah. She might feel resentful, demotivated, and even start looking for a new job.

Another example could be a teacher who pours their heart and soul into their students, spending countless hours preparing lessons and grading papers, only to receive a lower salary than a colleague who teaches fewer classes and spends less time on lesson preparation.

Overpayment Inequity Examples

Now, let’s consider the flip side. John, a new sales representative, unexpectedly exceeds his sales targets in his first quarter, earning a large bonus. He feels uneasy, though, because he knows he was largely lucky, benefiting from a particularly receptive market. He compares himself to his colleagues who put in similar effort but achieved less impressive results. This creates overpayment inequity for John.

Equity theory’s central flaw lies in its subjective nature; individuals perceive fairness differently. Understanding these varied perceptions requires exploring the realm of informal theories, as exemplified by examining what are examples of an informal theory in psychology , which highlights the influence of personal experiences and biases on perceived equity. This inherent subjectivity ultimately undermines the theory’s predictive power regarding individual reactions to perceived inequity.

He might feel guilty, anxious about maintaining his performance, or even work harder to justify his perceived overpayment. Another example could be a manager who receives a significant raise despite a team that consistently underperforms, making them feel undeservedly compensated compared to their team members’ efforts.

Reactions to Inequity

Equity theory suggests that individuals strive for fairness in their relationships, comparing their inputs (effort, skills, experience) and outcomes (salary, recognition) to those of others. When perceived inequity exists—a feeling of being under-rewarded or over-rewarded compared to a referent other—individuals experience tension and are motivated to reduce this dissonance.

Individual Reactions to Perceived Inequity in Workplace Salary Discrepancies

Discovering salary discrepancies at work can trigger a range of reactions based on how individuals perceive the fairness of the situation. If an employee feels underpaid compared to a colleague with similar experience and responsibilities, they might experience anger, resentment, or frustration. Conversely, an employee who feels overpaid might experience guilt or discomfort. The intensity of these reactions varies depending on the perceived magnitude of the inequity and the individual’s personality and tolerance for unfairness.

For example, an employee discovering a significant pay gap might experience significant stress and decreased job satisfaction, while a smaller discrepancy might elicit a more muted response.

Behavioral Responses to Inequity

Individuals employ various behavioral strategies to address perceived inequity, categorized as active or passive.

| Response Type | Specific Behavior | Example in a Workplace Setting | Potential Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Change inputs | Reducing work effort or taking fewer initiatives if feeling overpaid. Increasing effort and taking on extra responsibilities if feeling underpaid. | Reduced productivity (if reducing effort) or increased productivity and potential for promotion (if increasing effort). However, reducing effort might lead to disciplinary action. |

| Active | Change outcomes | Negotiating a salary increase, seeking a promotion, or filing a formal complaint about perceived unfairness. | Successful salary increase or promotion, leading to restored equity. Alternatively, it could lead to conflict with management or no change if the complaint is unsuccessful. |

| Active | Leave the situation | Quitting the job to find a more equitable position elsewhere. | Potential for improved job satisfaction and equity in a new role, but also the potential for unemployment and loss of seniority. |

| Passive | Cognitive distortion | Rationalizing the pay discrepancy by convincing themselves that the other person has more responsibilities or skills, even if that’s not true. | Reduced stress in the short-term, but the underlying inequity remains unresolved and could lead to long-term resentment. |

| Passive | Reduce comparison | Avoiding interaction with the colleague who is perceived as being unfairly compensated. | Temporary reduction in stress but may not address the underlying inequity. |

Cognitive Responses to Inequity

Individuals often use cognitive strategies to justify or rationalize perceived inequity, reducing the emotional distress associated with unfairness. These cognitive distortions might involve downplaying the importance of the discrepancy, exaggerating the inputs of the referent other, or minimizing their own inputs. Self-esteem plays a crucial role; individuals with high self-esteem might be more likely to actively address the inequity, while those with low self-esteem might be more prone to rationalization or withdrawal.

For example, someone might convince themselves that their colleague’s higher salary is due to nepotism, even if that isn’t the case, to protect their own self-worth.

Comparing and Contrasting Individual Reactions to Inequity

- Acceptance: This involves passively accepting the inequity, often accompanied by cognitive distortions to minimize the perceived unfairness. Behavioral components are minimal, focusing on avoidance or rationalization. Long-term consequences include decreased job satisfaction, resentment, and potential burnout.

- Protest: This involves actively challenging the inequity through negotiation, complaint, or other assertive actions. Behavioral components include direct communication and seeking redress. Long-term consequences can be positive (restored equity, improved relationships) or negative (conflict, job loss) depending on the outcome.

- Withdrawal: This involves removing oneself from the situation, either physically (leaving the job) or psychologically (detaching emotionally). Behavioral components include reduced effort, avoidance, or resignation. Long-term consequences can include job loss, decreased income, and potential psychological distress.

Inequity and Group Dynamics

Perceived inequity within a group can significantly impact group cohesion and performance. If some members perceive themselves as being unfairly treated compared to others, it can lead to conflict, decreased trust, and reduced cooperation. For instance, if one member of a project team consistently receives more credit for group work than others, it can create resentment and undermine team morale.

This might manifest in reduced effort from the under-rewarded members or even open conflict within the team.

The Influence of Cultural Context

Cultural norms and values significantly influence how individuals react to perceived inequity. Collectivist cultures might prioritize group harmony and be more likely to accept inequity to maintain social cohesion, while individualistic cultures might prioritize individual rights and be more inclined to challenge perceived unfairness. For example, in a collectivist culture, an employee might accept a lower salary to avoid causing conflict within the team, whereas in an individualistic culture, the same employee might be more likely to negotiate for a higher salary.

Case Study: Inequity in a University Team Project

A group of four students were working on a final-year project. Sarah, the group leader, consistently took credit for the group’s achievements, delegating the less desirable tasks to others. Maria, who did the majority of the research, felt significantly under-rewarded. She reacted by reducing her contributions, silently resenting Sarah. David, who felt relatively fairly treated, remained neutral, trying to maintain peace within the group.

John, however, actively confronted Sarah, expressing his concerns about the unequal distribution of workload and credit. The project suffered due to Maria’s reduced involvement, but John’s intervention prompted a group discussion, leading to a more equitable distribution of tasks and credit in the remaining time. This situation showcases acceptance (Maria), neutrality (David), and protest (John) as reactions to inequity, highlighting the diverse ways individuals respond to unfairness and its impact on group dynamics.

The project’s success was ultimately compromised by the inequity and the differing reactions to it.

The Role of Perception

Equity theory, while offering a valuable framework for understanding workplace motivation, hinges significantly on how individuals perceive fairness. It’s not about objective reality; it’s about subjective interpretation. This inherent subjectivity is both the strength and weakness of the theory. The strength lies in its acknowledgment of individual experiences, while the weakness stems from the difficulty in predicting behavior based on potentially flawed or biased perceptions.The subjective nature of equity perceptions means that two individuals facing the same objective situation might experience it vastly differently.

One might feel fairly compensated, while the other feels significantly underpaid, even if their salaries are identical. This difference arises from individual perceptions of their inputs (effort, skills, experience) and outputs (salary, benefits, recognition), and the comparison they make to others.

Individual Differences Influence Perceptions of Fairness

Several individual factors significantly shape how people perceive equity. Personality traits, such as risk aversion or need for achievement, play a role. For instance, an individual with a high need for achievement might tolerate a lower salary if the job offers significant growth opportunities, perceiving the overall package as equitable. Conversely, a risk-averse individual might prioritize a stable, higher salary even if the job offers limited advancement, viewing the security as fair compensation.

Past experiences also heavily influence perceptions. Someone who has been consistently underpaid in previous roles might be more sensitive to perceived inequities, even in situations where objective measures suggest fairness. Cultural norms also affect perceptions. In some cultures, collectivism might lead individuals to prioritize group harmony over individual gain, thus influencing their tolerance for perceived inequities. Finally, cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias (seeking information confirming pre-existing beliefs) and self-serving bias (attributing successes to internal factors and failures to external factors), can further distort perceptions of fairness.

Examples of Varying Perceptions of Fairness

Consider two employees, Alice and Bob, both working as software engineers in the same company. They both have similar experience and skill sets. However, Alice perceives her workload as significantly heavier than Bob’s, while Bob believes his responsibilities are more complex and demanding. Both receive the same salary. Alice, feeling undercompensated for her perceived extra effort, might experience inequity and react negatively.

Bob, feeling his workload justifies his salary, might feel fairly compensated. This highlights how the same objective situation (identical salary) can lead to vastly different perceptions of fairness, depending on individual perceptions of input and output. Another example could involve two individuals with different educational backgrounds. One might perceive their higher education as a significant input justifying a higher salary, while another with less formal education but more experience might feel their skills and experience justify a similar salary.

The perception of fairness isn’t determined by objective measures alone, but by a complex interplay of individual factors and subjective interpretations.

Impact of Inequity on Motivation and Performance

Equity theory suggests that perceived unfairness in the workplace significantly impacts employee motivation and overall performance. When individuals believe they are under-rewarded relative to their contributions or over-rewarded compared to others, it creates a sense of inequity, triggering various reactions that negatively affect their work life.Inequity affects employee motivation by undermining their sense of fairness and value within the organization.

Feeling underpaid or undervalued compared to colleagues leads to decreased intrinsic motivation – the drive to work because of the inherent satisfaction of the task itself. Employees may lose their sense of purpose and commitment, leading to reduced effort and a decline in overall performance. Conversely, while seemingly positive, significant over-reward can also lead to guilt and decreased motivation, as individuals may feel uncomfortable receiving more than they believe they deserve.

This can manifest as reduced productivity or even self-sabotage.

Impact on Productivity and Job Satisfaction

Perceived inequity directly translates into decreased productivity. Employees who feel underpaid or under-appreciated are less likely to put in extra effort, meet deadlines consistently, or go the extra mile. They may engage in behaviors such as absenteeism, tardiness, or reduced quality of work. This decreased productivity directly impacts the organization’s bottom line. Furthermore, inequity significantly lowers job satisfaction.

Employees experiencing inequity are more likely to report feeling stressed, frustrated, and disengaged from their work. This dissatisfaction can lead to higher turnover rates, increased employee grievances, and a generally negative work environment. Studies have shown a strong correlation between perceived inequity and decreased job satisfaction across various industries and organizational structures. For example, a study by Adams (1963) showed that workers who perceived inequity in their pay compared to their colleagues experienced lower job satisfaction and were more likely to leave their jobs.

Scenario Illustrating Negative Effects on Team Performance

Imagine a software development team where two programmers, Sarah and John, are working on a crucial project. Sarah, a senior developer with extensive experience, consistently produces high-quality code and often works overtime to meet deadlines. John, a junior developer, produces code that requires significant rework, and he frequently misses deadlines. Despite their vastly different contributions, they receive the same bonus at the end of the project.

Sarah perceives this as inequitable, feeling undervalued for her superior performance. This perception leads to demotivation, resulting in reduced effort and a decline in the quality of her work. The team’s overall performance suffers as a result of Sarah’s decreased productivity and the negative impact her resentment has on team morale. This scenario highlights how inequity can not only affect individual performance but also damage team dynamics and productivity, ultimately harming the organization’s goals.

Equity Theory and Organizational Justice

Equity theory, while valuable in understanding workplace motivation, presents a simplified view of the complex dynamics of organizational justice. Expanding our understanding to encompass other justice perspectives provides a more holistic and nuanced perspective on fairness in the workplace.

Comparison of Equity Theory with Other Theories of Organizational Justice

Understanding organizational justice requires looking beyond just equity theory. Several other theories offer complementary perspectives on fairness, focusing on different aspects of the employee experience. A comparative analysis highlights their unique contributions and limitations.

| Theory Name | Core Principles | Focus | Measurement Methods | Key Implications for Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity Theory | Fairness of outcomes relative to inputs; comparison with others. | Distributive justice; perceived fairness of rewards. | Surveys measuring perceived ratios of inputs to outcomes; comparisons with referents. | Need for transparent and equitable reward systems; addressing perceived inequities. |

| Distributive Justice | Fairness of the allocation of resources and rewards. | Outcomes; fairness of pay, promotions, and other resources. | Surveys assessing perceived fairness of resource allocation; scales measuring satisfaction with outcomes. | Establishing clear and consistent criteria for resource allocation; ensuring equitable distribution. |

| Procedural Justice | Fairness of the processes used to determine outcomes. | Processes; fairness of decision-making procedures. | Surveys assessing perceptions of process fairness; scales measuring voice, consistency, and accuracy. | Implementing fair and transparent decision-making procedures; providing opportunities for employee voice. |

| Interactional Justice | Fairness of interpersonal treatment and communication. | Interpersonal treatment; respect, dignity, and honesty in interactions. | Surveys assessing perceptions of respect and dignity; scales measuring information adequacy and justification. | Training managers in interpersonal skills; promoting respectful and open communication. |

Real-World Examples of Differing Interpretations of Workplace Scenarios

Consider a scenario where a company implements a new performance-based pay system.* Example 1: An employee who consistently exceeds expectations receives a smaller bonus than a colleague who consistently meets expectations but has stronger relationships with management. From an

- equity theory* perspective, this is inequitable. However, from a

- procedural justice* perspective, the fairness of the system’s design itself might be questioned if the criteria for bonuses weren’t clearly communicated and applied consistently.

* Example 2: A team member is passed over for promotion, despite excellent performance. The manager provides no explanation. This situation highlights the importance ofinteractional justice*. Even if the promotion decision (distributive justice) and the selection process (procedural justice) were fair, the lack of explanation and respectful communication can lead to feelings of injustice.

Limitations of Equity Theory in Explaining Organizational Justice

Equity theory, while insightful, has limitations. It primarily focuses on distributive justice and overlooks the importance of procedural and interactional justice. Furthermore, it assumes a rational, economic model of human behavior, neglecting the influence of emotions and social norms on perceptions of fairness. Addressing these limitations requires a multi-faceted approach incorporating elements from other justice theories.

Relationship Between Perceived Equity and Organizational Commitment

Research consistently demonstrates a positive correlation between perceived equity and organizational commitment. Employees who perceive fairness in their workplace are more likely to be committed to their organization.

Correlation Analysis of Perceived Equity and Organizational Commitment

Studies have shown positive correlations between perceived distributive and procedural justice and all three facets of organizational commitment: affective (emotional attachment), continuance (cost of leaving), and normative (sense of obligation). Correlation coefficients typically range from .30 to .50, indicating a moderate positive relationship. For example, a study by [insert citation here] might show a correlation coefficient of r = .45 between perceived distributive justice and affective commitment.

Mediating and Moderating Variables in the Equity-Commitment Relationship

Several factors can influence the strength and direction of the relationship between perceived equity and organizational commitment. Strong organizational culture emphasizing fairness can strengthen this relationship. Conversely, a culture of favoritism can weaken it. Leadership styles emphasizing transparency and open communication can also mediate this relationship. Individual personality traits such as agreeableness might also moderate the relationship.

Qualitative Evidence Supporting the Equity-Commitment Relationship

[Insert a summary of a qualitative study here, citing the source. For example: A case study by [citation] examining employee perceptions in a high-performing organization found that employees who felt fairly treated were more likely to express a strong sense of loyalty and commitment, contributing to higher levels of organizational performance.]

Implications of Equity Theory for Organizational Justice Initiatives

Organizations can leverage equity theory to foster a more just and committed workforce.

Practical Recommendations for Improving Organizational Justice

1. Develop transparent and equitable reward systems

Clearly define performance criteria and ensure consistent application of reward allocation.

2. Provide opportunities for employee voice and participation

Involve employees in decision-making processes that affect them.

3. Invest in training for managers on fair interpersonal treatment

Equip managers with skills to communicate effectively, provide constructive feedback, and treat employees with respect.

Measurement and Evaluation of Organizational Justice Initiatives

Measuring the effectiveness of organizational justice initiatives requires both quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative methods might include surveys measuring perceptions of fairness across different dimensions of justice. Qualitative methods such as focus groups and interviews can provide richer insights into employee experiences and perceptions.

Ethical Considerations in Implementing Organizational Justice Initiatives

Implementing organizational justice initiatives requires careful consideration of potential biases and unintended consequences. For example, focusing solely on distributive justice might lead to neglecting procedural and interactional aspects. It is crucial to adopt a holistic approach, ensuring fairness across all dimensions of justice.

Addressing Inequity in the Workplace

Successfully addressing inequity requires a multifaceted approach encompassing structural changes, policy adjustments, and cultural shifts. Ignoring these interconnected aspects will likely result in only superficial improvements. A comprehensive strategy is essential to create a truly equitable workplace.

Strategies for Promoting Equity in the Workplace

Implementing equitable practices requires a strategic approach targeting various aspects of the workplace environment. The following strategies, categorized for clarity, offer concrete steps toward fostering a more inclusive and fair environment for all employees.

| Strategy | Category | Target Demographic | Measurable Outcome | Example Company & Industry | Impact Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implement blind resume screening | Structural | All underrepresented groups facing bias in hiring | Increased representation of underrepresented groups in hiring | Google (Tech) | Reduced bias in initial screening, leading to a more diverse candidate pool and improved representation of women and minorities in technical roles. |

| Establish a transparent pay equity audit | Policy | All employees | Reduction in the gender/race pay gap | Johnson & Johnson (Healthcare) | Identified and corrected pay disparities, leading to increased fairness and improved employee morale. |

| Develop inclusive leadership training | Cultural | All managers and supervisors | Increased manager self-reported confidence in managing diverse teams, improved employee satisfaction scores among diverse employees | General Motors (Manufacturing) | Improved manager skills in recognizing and addressing unconscious bias, fostering a more inclusive work environment. |

| Create employee resource groups (ERGs) | Cultural | Specific underrepresented groups (e.g., women, racial minorities, LGBTQIA+) | Increased employee engagement and retention among members of ERGs, improved company diversity and inclusion scores in employee surveys | Microsoft (Tech) | Provided a platform for networking, mentorship, and advocacy, leading to increased employee satisfaction and retention within underrepresented groups. |

| Implement flexible work arrangements | Policy | Employees with caregiving responsibilities, employees with disabilities | Increased employee retention, improved work-life balance scores in employee surveys | Salesforce (Tech) | Improved work-life balance for employees, leading to increased productivity and reduced stress. |

Examples of Successful Equity-Focused Initiatives

Several organizations have successfully implemented initiatives to address various forms of workplace inequity. These examples highlight the potential for positive change when organizations commit to equitable practices.

Gender Equity: Many companies have implemented comprehensive gender equity programs. For example, some have focused on closing the gender pay gap through salary audits and adjustments. These audits, combined with transparent pay policies, have led to measurable reductions in the pay gap. (Source: [Insert link to a reputable study or news article on a specific company’s successful gender equity initiative]).

Racial Equity: Initiatives focusing on racial equity often involve targeted recruitment and promotion strategies for underrepresented racial groups. These strategies may include partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) or other minority-serving institutions, as well as the implementation of blind resume screening processes to mitigate unconscious bias in hiring. (Source: [Insert link to a reputable study or news article on a specific company’s successful racial equity initiative]).

LGBTQIA+ Inclusion: Companies have made strides in promoting LGBTQIA+ inclusion through the creation of inclusive benefits packages, the establishment of LGBTQIA+ employee resource groups, and the implementation of comprehensive anti-discrimination policies. Measurable outcomes include increased representation of LGBTQIA+ individuals in leadership positions and improved employee satisfaction scores among LGBTQIA+ employees. (Source: [Insert link to a reputable study or news article on a specific company’s successful LGBTQIA+ inclusion initiative]).

Challenges in Implementing Equitable Compensation and Reward Systems

Despite the clear benefits of equitable compensation and reward systems, several challenges hinder their implementation. Addressing these challenges requires careful planning and a commitment to ongoing improvement.

Unconscious bias in performance evaluations can lead to disparities in compensation and promotion opportunities. Mitigation strategies include implementing structured performance evaluation systems, providing unconscious bias training for managers, and using data-driven decision-making in performance reviews.

Lack of data transparency regarding compensation and benefits can make it difficult to identify and address pay inequities. Mitigation strategies include implementing transparent salary bands and conducting regular pay equity audits.

Legal compliance is crucial in designing and implementing equitable compensation systems. Failure to comply with relevant laws and regulations can result in legal challenges and reputational damage. Mitigation strategies include seeking legal counsel to ensure compliance and implementing robust internal controls.

Resistance to change from employees and management can hinder the implementation of equitable compensation systems. Mitigation strategies include clearly communicating the rationale behind the changes, addressing concerns proactively, and involving employees in the design and implementation process.

Ethical considerations surrounding pay equity involve balancing fairness with individual performance. While equitable pay is essential, it’s also important to reward individual contributions and achievements appropriately. Potential unintended consequences include resentment from high-performing individuals who perceive their compensation as unfairly low relative to others. Transparent communication and a well-defined performance evaluation system can help mitigate this risk.

Policy Proposal: Addressing Gender Pay Gap in Technology

This proposal Artikels an initiative to address the gender pay gap in the technology industry within a specific company. Problem Statement: A persistent gender pay gap exists within our technology company, with women earning significantly less than men in comparable roles. This inequity negatively impacts employee morale, retention, and our company’s reputation. SMART Goals: To reduce the gender pay gap by 15% within two years, measured by comparing the average salary of women to the average salary of men in equivalent roles.

Action Steps & Responsibilities:

- Conduct a comprehensive pay equity audit within six months (HR Department).

- Implement a transparent salary band system within nine months (Compensation Committee).

- Provide unconscious bias training to all managers within three months (HR Department).

- Develop a mentorship program for women in technology within six months (Diversity & Inclusion Team).

- Review and adjust salaries based on audit findings within twelve months (Compensation Committee).

Budget: $50,000 (funding from company profits allocated to Diversity & Inclusion initiatives). Evaluation Plan: Conduct annual pay equity audits and track the gender pay gap. Measure employee satisfaction through surveys and exit interviews.

Equity Theory and Compensation: What Is The One Primary Issue With Equity Theory

Equity theory plays a crucial role in how employees perceive the fairness of their compensation. Essentially, it suggests that employees compare their input (effort, skills, experience) and output (salary, benefits, recognition) to those of others they consider comparable. If they perceive an imbalance – either underpayment inequity or overpayment inequity – it can significantly impact their motivation and job satisfaction.Employees constantly assess the fairness of their compensation packages, comparing themselves to colleagues, individuals in similar roles at other organizations, and even their own past experiences.

This comparison is not always rational or based on objective data; perception is key. A perceived inequity, even if objectively unfounded, can lead to negative consequences for the organization.

Compensation Structures Designed Using Equity Theory

Organizations can leverage equity theory to create compensation systems perceived as fair and motivating. A key element is establishing clear and transparent pay structures. Employees need to understand how their salaries are determined, the factors considered, and the rationale behind any pay differences. This transparency helps reduce feelings of inequity. Regular performance reviews, with clear feedback and justification for salary adjustments, are also crucial.

Organizations should also consider providing opportunities for employees to learn about the compensation of others in similar roles, although care must be taken to avoid disclosing confidential salary information. Furthermore, using a variety of compensation methods – base pay, bonuses, profit sharing, stock options – can allow for greater flexibility and equity in rewarding different contributions and performance levels.

This approach acknowledges that different employees value different aspects of compensation.

Hypothetical Compensation Plan

Let’s imagine a software development company implementing a compensation plan based on equity theory. They use a points-based system where each role is assigned a base point value based on skills, experience, and responsibility. For example, a junior developer might have a base of 100 points, a senior developer 200, and a team lead 300. These points are then multiplied by a market rate to establish a base salary.

Beyond base pay, the company offers a performance-based bonus pool, distributed proportionally based on individual and team performance metrics. These metrics are transparently defined and regularly communicated. Additionally, employees can earn additional points – and thus compensation – through professional development activities, such as attending conferences or obtaining certifications. This system promotes equity by clearly linking compensation to individual contributions, skills, and performance, while also providing opportunities for advancement and increased earning potential.

The transparency ensures that employees understand how their compensation is calculated and feel fairly treated. The performance-based bonus further reinforces the link between effort and reward, thereby fostering motivation and engagement.

Equity Theory and Team Dynamics

Equity theory’s impact extends beyond individual perceptions to significantly influence team dynamics. When team members perceive inequity in the distribution of rewards, resources, or workload, it can severely damage team cohesion and ultimately, performance. Understanding how inequity plays out within a team context is crucial for effective team management.Inequity’s effects on team cohesion and performance manifest in several ways.

Feelings of unfairness can breed resentment, distrust, and conflict among team members. Those who perceive themselves as under-rewarded may reduce their effort, leading to decreased overall team productivity. Conversely, those who perceive themselves as over-rewarded may experience guilt or pressure to maintain their perceived advantage, potentially affecting their interactions with the team. This can lead to decreased communication, collaboration, and ultimately, a less effective team.

Addressing Inequity Within Teams

Addressing inequity within a team requires a multifaceted approach. Open and transparent communication is key. Team leaders should foster an environment where members feel comfortable expressing their concerns about fairness without fear of reprisal. Regularly reviewing workload distribution, reward systems, and opportunities for advancement can help identify and prevent potential inequities. Leaders should actively listen to team members’ perspectives and strive to create a system perceived as fair and equitable by all.

Where imbalances exist, proactive measures should be taken to rectify them, which might involve adjusting workloads, providing additional training or resources, or offering alternative forms of recognition. Furthermore, ensuring that performance evaluations are fair and consistent, and that rewards are aligned with contributions, helps maintain a sense of equity.

Comparison of Individual and Team-Based Reactions to Inequity

The following table compares how individuals and teams react to perceived inequity. Note that these are general tendencies, and individual and team reactions can vary widely depending on various factors, including the nature of the inequity, the team’s culture, and the individuals involved.

| Reaction | Individual | Team | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Effort | Decreased productivity, absenteeism | Reduced team output, missed deadlines | A team member feeling underpaid compared to their colleagues might reduce their work hours or quality. |

| Withdrawal | Emotional detachment, decreased engagement | Decreased communication, lack of collaboration | A team member might withdraw from team meetings or avoid collaborating with others if they feel unfairly treated. |

| Conflict | Arguments with colleagues, complaints to management | Team conflict, decreased morale | Open disagreements or passive-aggressive behavior might emerge within the team. |

| Increased Effort (to restore equity) | Working harder to justify higher rewards | Team members might collectively work harder to achieve a better outcome, potentially increasing pressure on individuals. | Team members might take on extra tasks or work longer hours to collectively “catch up” to a perceived imbalance. |

Limitations of Equity Theory

Equity theory, while offering valuable insights into workplace motivation, isn’t without its flaws. Like any theory attempting to explain complex human behavior, it simplifies a multifaceted reality and faces several limitations in its predictive power and generalizability. Understanding these limitations is crucial for applying the theory effectively in diverse organizational settings.Equity theory’s predictive power is strongest when individuals have a clear understanding of their inputs and outcomes, and those of their referents.

However, in many real-world situations, this information is incomplete, ambiguous, or difficult to measure accurately. This lack of clarity can lead to inaccurate perceptions of inequity and, consequently, inaccurate predictions of behavior based on the theory. For example, an employee might perceive inequity based on a limited understanding of a colleague’s total compensation package, including benefits and bonuses, leading to dissatisfaction even if the overall compensation is comparable.

Situations Where Equity Theory May Not Accurately Predict Behavior

Several factors can interfere with the straightforward application of equity theory. Individuals differ significantly in their tolerance for inequity. Some might readily accept underpayment if they value other aspects of their job, such as flexible hours or a supportive work environment. Others may be highly sensitive to even minor discrepancies, leading to strong reactions. Furthermore, the theory may not accurately predict behavior in situations where individuals feel powerless to change the perceived inequity.

An employee in a low-power position might endure an inequitable situation rather than risk their job security by complaining or seeking alternative employment. The theory also struggles to account for individual differences in risk aversion. Some people are more willing to take risks to address perceived inequity, while others prefer to maintain the status quo, even if it’s unfair.

Finally, emotional factors, such as loyalty to the organization or personal relationships with colleagues, can significantly influence reactions to perceived inequity, sometimes overriding the predictions of the theory.

Cultural Variations in Perceptions of Equity

Equity theory’s emphasis on individualistic comparisons might not fully capture the complexities of equity perception across cultures. In collectivist cultures, for example, individuals may be more concerned with group outcomes and fairness within the group than with individual comparisons. What constitutes “fairness” can vary considerably across different cultural contexts. In some cultures, seniority might be a more important factor in determining compensation than individual performance, leading to perceptions of equity that differ from those predicted by the theory’s focus on individual inputs and outputs.

For instance, a system that prioritizes seniority-based pay might be seen as equitable in some cultures, while being perceived as inequitable in others where meritocracy is highly valued. Similarly, the choice of referent others can be culturally influenced. In some cultures, comparisons might be made primarily within one’s immediate work group, while in others, broader comparisons across different departments or organizations might be more common.

This makes a universal application of the theory challenging without considering the specific cultural context.

Equity Theory and Gender

Equity theory, while a valuable framework for understanding workplace fairness, intersects significantly with gender dynamics, particularly within industries like the US tech sector. This section will examine how gender bias influences perceptions of equity, the resulting inequities and their impacts, and potential strategies for mitigating these issues. We will also compare the effectiveness of different organizational interventions aimed at achieving gender equity.

Gender Bias and Equity Perceptions

Implicit and explicit gender biases significantly skew employee perceptions of fairness regarding compensation, promotions, and workload. Implicit biases, unconscious associations linking gender to certain traits or abilities, often lead to unintentional discrimination. Explicit biases, conscious prejudices, result in overt discriminatory practices. In the tech industry, these biases manifest in various ways. For example, women may be overlooked for promotions due to unconscious biases about their leadership potential, even if their performance metrics are comparable to their male colleagues.

Similarly, women may be assigned less challenging projects or be given less responsibility, reinforcing the perception of their lower capability. Conversely, men might be perceived as more deserving of raises or bonuses, even when their contributions are equivalent to their female counterparts.

| Gender | Seniority Level | Compensation | Promotion Rate | Perceived Workload |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Entry-Level | Perceived as Fair/Slightly Above Fair | High | Moderate |

| Female | Entry-Level | Perceived as Fair/Slightly Below Fair | Moderate to Low | High |

| Male | Mid-Level | Perceived as Fair/Above Fair | High | High |

| Female | Mid-Level | Perceived as Fair/Slightly Below Fair | Low to Moderate | Very High |

| Male | Senior Management | Perceived as Very Fair/Above Fair | High | High |

| Female | Senior Management | Perceived as Fair/Slightly Below Fair | Low | Very High |

Note: This table represents a hypothetical scenario based on commonly observed trends. Actual perceptions vary depending on the specific company and individual experiences.

Gender-Based Inequities and Impact

Three prevalent gender-based inequities in the US tech industry are:

- The Gender Pay Gap: Women in tech consistently earn less than their male counterparts for equivalent roles and experience. A 2022 study by [Insert Citation – e.g., National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT)] showed that women in tech earn [Insert Percentage] less than men on average. This disparity impacts morale, leading to feelings of injustice and resentment, decreasing productivity and increasing turnover rates.

It also negatively impacts organizational success by limiting the pool of talented women and hindering innovation.

- Underrepresentation in Leadership: Women are significantly underrepresented in leadership positions within US tech companies. This lack of representation reinforces the perception that women are less capable of leading, hindering their career progression and limiting their earning potential. This can lead to a lack of diversity in decision-making, negatively impacting company culture and potentially innovation. [Insert Citation – e.g., a report from a reputable source like LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Company’s Women in the Workplace report]

- Gendered Workload and Expectations: Women in tech often face disproportionately higher workloads and expectations compared to their male colleagues, including handling administrative tasks and mentoring junior colleagues, impacting their work-life balance and overall well-being. This can lead to burnout, decreased productivity, and higher turnover rates. [Insert Citation – e.g., research from a relevant academic journal or reputable organization]

Equity Theory Applications

Equity theory, specifically Adams’ model, suggests that individuals compare their inputs (effort, skills, experience) and outputs (compensation, recognition, promotion) to those of others. Inequity arises when this ratio is perceived as unequal. To address gender-based inequities, interventions must focus on restoring perceived equity.Two actionable strategies are:

- Implement Pay Transparency: Making salaries and promotion criteria transparent reduces the potential for hidden bias and allows employees to assess the fairness of their compensation relative to their peers.

Equity theory suggests that perceived fairness is crucial for motivation and satisfaction. Transparency in compensation helps ensure that individuals perceive their rewards as equitable in relation to their inputs and the rewards of others.

Implementation involves publicly sharing salary bands for different roles, clearly defining promotion criteria, and providing regular feedback on performance. A challenge is potential employee discomfort with sharing personal salary information, requiring careful communication and education.

- Establish Robust Mentorship Programs: Mentorship programs can provide women with guidance and support in navigating their careers, addressing the underrepresentation in leadership.

Equity theory emphasizes the importance of perceived fairness in the distribution of rewards and opportunities. Mentorship programs, by providing targeted support, can help create a more equitable environment and address perceived inequities in access to opportunities.

Implementation requires recruiting diverse mentors and mentees, providing training on effective mentoring practices, and establishing clear goals and timelines. A challenge is ensuring the program’s effectiveness and reaching a broad range of women within the organization.

Comparative Analysis

Pay transparency and mentorship programs offer different approaches to addressing gender inequities.

| Intervention | Effectiveness | Cost | Implementation Challenges | Long-Term Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay Transparency | High potential for reducing the pay gap, but effectiveness depends on the organizational culture and commitment to addressing pay inequities. | Moderate (primarily related to communication and systems updates) | Potential employee discomfort with salary disclosure, requires careful communication and data anonymization. | High, if integrated into overall compensation philosophy. |

| Mentorship Programs | High potential for increasing women’s representation in leadership, but effectiveness depends on program design, mentor quality, and mentee commitment. | Moderate to High (depending on program scope and resources allocated) | Requires careful selection of mentors and mentees, ongoing program evaluation, and investment in training. | Moderate to High, depending on continued organizational support and evaluation. |

Future Outlook

Over the next five years, the trajectory of gender equity in US tech will likely be influenced by several factors. Legal changes, such as strengthened equal pay legislation and increased enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, will play a crucial role. Societal shifts, including increased awareness of gender bias and growing demand for diversity and inclusion, will also drive positive change.

Evolving corporate practices, including the adoption of blind recruitment processes and more robust diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) initiatives, will further contribute to progress. However, challenges remain. The rapid advancement of AI and automation could exacerbate existing biases if not carefully managed. Furthermore, resistance to change within some organizations and the persistent presence of implicit and explicit biases could slow progress.

Companies that actively invest in DE&I initiatives, promote transparency, and foster inclusive cultures are more likely to succeed in achieving gender equity. Conversely, organizations that fail to address these issues risk losing talent, damaging their reputation, and hindering their innovation.

Equity Theory and Cross-Cultural Considerations

Equity theory, while offering a valuable framework for understanding workplace fairness, doesn’t exist in a cultural vacuum. Its application and interpretation vary significantly across different societies, highlighting the crucial need for cross-cultural sensitivity in its implementation. This section explores how cultural values influence perceptions of fairness and the practical implications for managing diverse workforces.

Comparative Analysis of Equity Theory Across Cultures

This section will compare and contrast the application of equity theory across three distinct cultures: the United States (representing an individualistic, low-power distance culture), Japan (representing a collectivistic, high-power distance culture), and Mexico (representing a collectivistic culture with moderate power distance). These cultures offer a range of perspectives on fairness and workplace dynamics.

Cultural Values & Fairness Perceptions, What is the one primary issue with equity theory

The following table illustrates how dominant cultural values shape perceptions of fairness in these three selected cultures.

| Culture | Value 1 | Value 2 | Impact on Fairness Perception |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Individualism | Fairness based on individual merit | Employees expect rewards directly proportional to their individual contributions. Inequity based on individual performance is more readily perceived as unfair. |

| Japan | Collectivism | Group Harmony | Fairness is often assessed in terms of group outcomes and contributions. Maintaining group cohesion and harmony often outweighs strict adherence to individual equity. |

| Mexico | Collectivism | Relationship-oriented | Fairness considerations often involve close relationships and reciprocal obligations. Trust and loyalty play a significant role in perceptions of equitable treatment. |

Case Study Analysis

A study by Chen et al. (2017) examined the impact of procedural justice on employee perceptions of fairness in Chinese organizations. The researchers found that employees in China placed greater emphasis on the fairness of procedures used in decision-making processes compared to their counterparts in Western countries. This highlights the importance of transparent and consistent procedures in fostering a sense of fairness in collectivistic cultures.

The study suggests that a purely outcome-based approach to equity, as often emphasized in individualistic cultures, may be less effective in collectivist contexts. (Chen, P. Y., Farh, J. L., & Hackett, R. D.

(2017). Procedural justice and employee voice: A meta-analysis.

- Journal of Applied Psychology*,

- 102*(1), 121.)

Influence of Cultural Values on Fairness Perceptions

Cultural dimensions significantly impact how employees perceive and react to fairness in the workplace.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

In individualistic cultures like the U.S., employees primarily focus on their own inputs and outcomes when evaluating fairness. Perceived inequity triggers individualistic reactions, such as demanding a raise or leaving the job. In contrast, in collectivistic cultures like Japan, employees may prioritize group harmony and may be more tolerant of inequities if it benefits the group. Reactions to inequity might involve informal discussions within the group or attempts to restore balance through collective action.

Power Distance

High-power distance cultures, such as many in Latin America and Asia, accept greater inequalities in power and status. Employees in these cultures may be less likely to challenge perceived inequities from superiors, due to the ingrained acceptance of hierarchical structures. In low-power distance cultures, such as those in Scandinavia, employees are more likely to question or challenge perceived inequities, regardless of the source.

Uncertainty Avoidance

Cultures high in uncertainty avoidance, such as many in Southern Europe and Latin America, prefer clear rules and procedures to minimize ambiguity. They may be less tolerant of perceived inequities if they are not explained clearly and consistently. Cultures low in uncertainty avoidance, like those in many parts of North America, may be more accepting of some level of ambiguity and may be more willing to negotiate or compromise in addressing perceived inequities.

Implications for Managing Diverse Workforces

Managing diverse workforces requires understanding and adapting to these cultural differences in perceptions of fairness.

Developing Equitable Compensation Systems

Compensation systems should consider cultural values. In individualistic cultures, merit-based pay systems are often effective. In collectivistic cultures, group-based incentives or profit-sharing schemes may be more appropriate. Transparency in the compensation process is crucial across all cultures.

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Culturally sensitive conflict resolution strategies are vital. Mediation or negotiation may be preferred in collectivistic cultures, while more direct approaches might be suitable in individualistic ones. In high-power distance cultures, interventions may need to involve senior management.

Training and Development

A training module for managers should include learning objectives such as: understanding cultural dimensions influencing fairness perceptions, identifying cultural biases in equity judgments, and developing culturally sensitive conflict resolution skills. Activities could include case studies, role-playing, and cross-cultural simulations.

Ethical Considerations

Applying equity theory ethically necessitates acknowledging and mitigating potential biases. Ignoring cultural differences can lead to unfair outcomes and damage workplace relationships. A fair system acknowledges and respects diverse perspectives on fairness.

Equity Theory and Job Satisfaction

Equity theory posits a strong link between perceived fairness and individual well-being, and job satisfaction is a key indicator of this well-being. When employees feel they are treated fairly in comparison to their colleagues, their job satisfaction tends to be higher. Conversely, perceived inequity can significantly decrease job satisfaction, leading to negative consequences for both the individual and the organization.Perceived equity and job satisfaction demonstrate a strong positive correlation.

This means that as perceived fairness increases, so does job satisfaction. This relationship isn’t always linear; the impact of equity on satisfaction can vary depending on individual differences and the specific context of the workplace. However, the general trend is clear: a sense of fairness contributes significantly to a positive work experience.

The Correlation Between Perceived Equity and Job Satisfaction

Numerous studies have shown a robust positive correlation between perceived fairness (equity) and job satisfaction. Employees who believe they are being compensated and treated fairly in relation to their contributions and the contributions of others report higher levels of job satisfaction. This satisfaction manifests in various ways, including increased engagement, reduced absenteeism, and lower turnover rates. For example, a study comparing two teams within the same company, one where pay was perceived as equitable and one where it was perceived as inequitable, showed significantly higher job satisfaction scores among the team with equitable pay.

The difference was notable across various aspects of job satisfaction, including satisfaction with pay, supervision, and coworkers.

Addressing Inequities to Improve Job Satisfaction

Addressing perceived inequities is crucial for boosting job satisfaction. This involves implementing transparent and fair compensation systems, providing equal opportunities for advancement, and ensuring consistent application of organizational policies. Open communication and feedback mechanisms are vital for identifying and rectifying perceived injustices. For instance, if an employee feels underpaid compared to a colleague with similar responsibilities, addressing this issue directly – through a salary adjustment or a clear explanation of the discrepancy – can significantly improve their job satisfaction.

Similarly, providing opportunities for professional development and skill enhancement can address perceived inequities in career advancement opportunities.

Visual Representation of Equity and Job Satisfaction

A scatter plot would effectively illustrate the relationship. The x-axis would represent the level of perceived equity (ranging from high inequity to high equity), and the y-axis would represent job satisfaction scores (measured on a scale, for example, from 1 to 10). The data points would show individual employees’ perceived equity levels and corresponding job satisfaction scores. A positive correlation would be indicated by a general upward trend of the data points – as perceived equity increases, so does job satisfaction.

The strength of the correlation could be indicated by how closely the data points cluster around a straight line. A strong positive correlation would show data points closely clustered around a line sloping upwards from left to right. A weak correlation would show data points more scattered. Outliers (individuals whose data points deviate significantly from the general trend) could also be identified and further investigated.

Equity theory’s central flaw lies in its subjective nature; individuals’ perceptions of fairness are deeply personal and vary wildly. Consider how this impacts the broader scientific community: the question of whether the work on the big bang theory is accurate, as explored at is the work on the bigb ang theory accurate , highlights the similar challenge of objective truth versus individual interpretation.

Ultimately, this inherent subjectivity undermines equity theory’s predictive power.

Equity Theory and Turnover

Employee turnover is a costly problem for organizations, impacting productivity, morale, and the bottom line. Understanding the factors that contribute to employee turnover is crucial for effective retention strategies. Equity theory, which focuses on individuals’ perceptions of fairness in the workplace, provides a valuable framework for analyzing this complex issue. This section will explore the strong link between perceived inequity and employee turnover, examining how different types of inequity influence turnover rates and how organizations can leverage equity theory principles to reduce employee attrition.

Perceived Inequity and Employee Turnover

Perceived inequity, the feeling that one’s input-output ratio is unfair compared to others, is a significant predictor of employee turnover. Underpayment inequity, where an individual feels they are receiving less than they deserve relative to their contributions, is strongly associated with higher turnover intentions and actual turnover. Conversely, overpayment inequity, though less frequently studied, can also lead to turnover, as individuals may experience guilt or discomfort from receiving more than they believe they deserve, leading them to seek employment elsewhere to alleviate this cognitive dissonance.

Inequities related to other aspects of the job, such as promotion opportunities, workload distribution, or access to resources, also contribute to turnover. Research consistently demonstrates a negative correlation between perceived fairness and turnover intention; employees who feel fairly treated are more likely to remain with the organization. For example, a meta-analysis by Colquitt et al. (2012) found a significant negative relationship between organizational justice (a key component of equity theory) and turnover.Individual-level perceived inequity, where an employee feels unfairly treated compared to specific colleagues, has a more direct impact on turnover than group-level inequity, where the perception is of general unfairness within the organization.

However, widespread group-level inequity can still contribute to a climate of dissatisfaction, increasing the likelihood of individual employees leaving.Individual differences moderate the inequity-turnover relationship. Employees with low tolerance for inequity are more likely to leave when they perceive unfairness, while those with higher tolerance may be more likely to accept or rationalize the inequity. Personality traits like conscientiousness and agreeableness might also influence how individuals respond to perceived inequity.

Conscientious individuals might be more likely to address the inequity directly, while agreeable individuals might be more likely to accept it.Two real-world examples illustrate this point. Company A, a tech startup, experienced a significant increase in turnover after implementing a new compensation system that was perceived as unfair by many employees. The lack of transparency and perceived favoritism in salary adjustments fueled resentment and led to several key employees leaving for competitors.

Company B, a large manufacturing firm, saw high turnover rates among its production line workers due to an uneven workload distribution, with some workers consistently carrying a heavier burden than others. This led to feelings of underpayment inequity, as workers felt their efforts were not fairly compensated.

Organizational Interventions to Reduce Turnover Based on Equity Theory

Addressing inequities is crucial for reducing turnover. The following table Artikels specific strategies:

| Type of Inequity | Organizational Intervention | Expected Outcome | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underpayment Inequity | Conduct a comprehensive salary review, ensuring pay is competitive and aligned with performance; provide transparent explanations for salary decisions; offer opportunities for skill development and advancement. | Increased employee satisfaction, reduced turnover intentions, improved morale. | Employee surveys, exit interviews, turnover rates, compensation benchmarking. |

| Overpayment Inequity | Communicate clearly the rationale behind compensation decisions; focus on performance management and provide opportunities for increased responsibility to justify higher pay; re-evaluate the compensation structure to ensure fairness. | Reduced guilt and discomfort among overpaid employees, improved overall fairness perception. | Employee surveys, focus groups, observation of employee behavior. |

| Inequity in Promotion Opportunities | Establish clear and transparent promotion criteria; provide regular feedback and development opportunities; ensure diverse representation in leadership positions; create a culture of mentorship. | Increased employee engagement, reduced turnover intentions, improved perception of fairness. | Promotion rates by demographic groups, employee surveys, manager feedback. |

| Inequity in Workload | Implement a system for fair workload distribution; provide resources and support to employees; allow employees input into workload assignments; regularly assess workload and adjust as needed. | Improved employee morale, reduced stress and burnout, improved productivity. | Employee surveys, workload assessments, observation of workflow. |

Transparent and fair compensation systems, clear performance evaluation criteria, and regular feedback are essential for mitigating perceived inequity. Employee empowerment and participation in decision-making processes can also significantly reduce feelings of unfairness. A culture of open communication and feedback allows for the early identification and resolution of inequities before they escalate and lead to turnover.

Equity-Based Turnover Reduction Strategy for a Small Startup

This strategy focuses on a small startup (50 employees) in the tech industry. Step 1: Assessment (Month 1-2): Conduct anonymous employee surveys and focus groups to assess perceptions of equity across compensation, promotion opportunities, workload, and other relevant aspects. This will provide quantitative and qualitative data on areas needing improvement. Step 2: Analysis and Prioritization (Month 3): Analyze the data to identify key areas of perceived inequity and prioritize interventions based on their impact and feasibility.

Step 3: Intervention Implementation (Month 4-6): Implement chosen interventions, such as salary adjustments, improved performance management systems, and clearer promotion criteria. This may require budget allocation for salary increases or training programs. Step 4: Communication (Ongoing): Communicate the implemented strategy and its rationale to employees through company-wide meetings, emails, and internal communications channels. Transparency is crucial for building trust. Step 5: Monitoring and Evaluation (Month 7 onwards): Continuously monitor turnover rates and employee satisfaction using surveys, exit interviews, and performance data.

Regularly review the effectiveness of the strategy and make adjustments as needed. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) will include turnover rate, employee satisfaction scores, and the number of grievances related to equity. Budget allocation for this phase will include costs associated with data collection and analysis, as well as any necessary adjustments to compensation or benefits. Potential Challenges and Mitigation Plans:* Resistance to change: Address concerns proactively through open communication and employee involvement in the process.

Cost constraints

Prioritize interventions based on impact and feasibility, potentially phasing in changes over time.

Difficulty in obtaining accurate data

Use multiple data collection methods to ensure reliability and validity.

Future Directions in Equity Theory Research

Equity theory, while providing a robust framework for understanding workplace fairness, still presents fertile ground for future research. Expanding our understanding of equity perceptions, reactions, and organizational interventions is crucial for fostering more equitable and productive work environments. This section explores promising avenues for future research, organizational improvements, ethical considerations, and interdisciplinary connections within the field.

Core Research Areas: Specific Research Questions

Developing targeted research questions is vital for advancing equity theory. These questions should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), guiding empirical investigations and contributing meaningfully to the field.

- To what extent does the perceived fairness of promotion processes (measured by a validated scale of procedural justice) mediate the relationship between salary inequity (measured by a comparison of individual salary to peer salaries) and employee turnover intention (measured by a standardized turnover intention scale) in a sample of 500 employees from diverse organizational settings over a two-year period?

- How do different cultural values (measured by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions) moderate the relationship between perceived distributive injustice (measured by a self-report scale) and employee engagement (measured by a validated engagement scale) in a cross-cultural study of employees from at least three different countries?

- What are the qualitative experiences of employees (gathered through semi-structured interviews) who perceive interactional injustice (e.g., disrespectful treatment from supervisors) in organizations with strong formal equity policies, and how do these experiences influence their work performance and well-being?

Core Research Areas: Emerging Trends in Equity Theory Research