What is the basic idea behind disengagement theory? It’s a compelling question that delves into how individuals and society interact as we age. This theory suggests a natural process of mutual withdrawal occurs between older adults and society, leading to decreased social interaction and a gradual disengagement from roles and responsibilities. While seemingly simple, this concept has sparked extensive debate and generated alternative perspectives, such as activity theory and continuity theory, each offering unique insights into successful aging.

We’ll explore the core tenets of disengagement theory, its strengths and weaknesses, and its relevance in today’s ever-evolving social landscape.

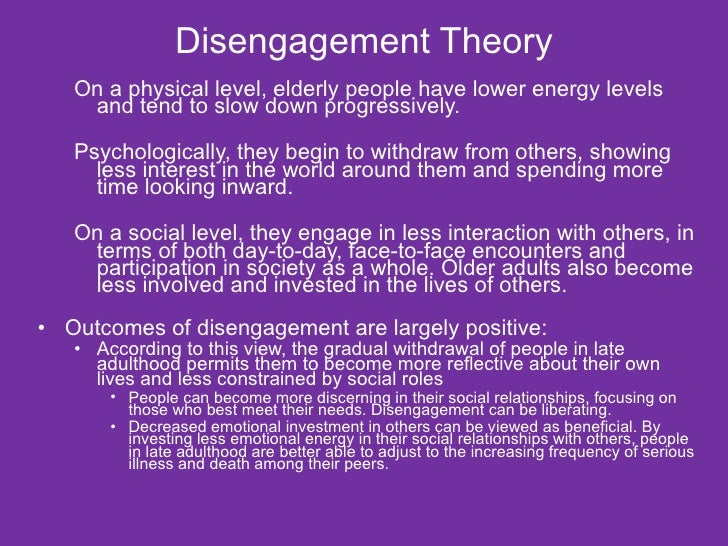

Disengagement theory, first proposed in the mid-20th century, posits that aging is a process of reciprocal withdrawal. Older adults gradually disengage from social roles and activities, while society, in turn, reduces its expectations and involvement with them. This isn’t necessarily a negative process, according to proponents; rather, it’s a natural and adaptive response to the physical and psychological changes associated with aging.

However, critics argue that this perspective overlooks the importance of social interaction and active engagement in maintaining well-being in later life. Alternative theories, like activity theory, which emphasizes the importance of continued social involvement, offer contrasting views, leading to a complex and multifaceted understanding of aging and social participation.

Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory, a prominent perspective in gerontology, proposes a natural and inevitable decline in social interaction and activity levels as individuals age. This theory, developed in the mid-20th century, significantly shaped our understanding of aging, though it has since faced considerable critique.

Historical Context of Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory emerged in the 1960s, a period marked by significant societal shifts. Key figures like Cumming and Henry (1961) are credited with its development, their influential work,

Growing Old

The Process of Disengagement*, laying the groundwork for the theory. The prevailing social and psychological perspectives of the time emphasized societal roles and the life cycle. Post-World War II societal changes, including increased life expectancy and the growth of the elderly population, contributed to a focus on the aging process. The theory’s initial reception was largely positive, reflecting the societal acceptance of age-related withdrawal.

However, its inherent assumptions about aging and its lack of consideration for individual agency led to significant critiques in subsequent years. These critiques stemmed from concerns about the potential for reinforcing ageist stereotypes and neglecting the diverse experiences of older adults.

Definition of Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory posits that aging involves a mutual withdrawal between the individual and society. This withdrawal is considered a natural and adaptive process, allowing individuals to gracefully transition out of their social roles and prepare for death. Unlike activity theory, which emphasizes the importance of maintaining social engagement for successful aging, disengagement theory suggests that reduced social involvement is not necessarily detrimental.

Unlike continuity theory, which focuses on maintaining consistent patterns of behavior throughout life, disengagement theory focuses on a shift in patterns of social interaction. Core tenets include the idea that disengagement is reciprocal (both individual and society withdraw), and that it is a functional process, facilitating a peaceful transition into later life.

Societal Expectations Related to Aging and Disengagement

Societal expectations regarding aging and disengagement vary widely across cultures and socioeconomic groups.

| Culture/Group | Expectation Regarding Disengagement | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Western Industrialized Societies | Retirement from workforce | Mandatory retirement age of 65 |

| Many East Asian Cultures | Increased family responsibility and caregiving for elders | Adult children providing financial and emotional support to aging parents |

| Some Indigenous Cultures | Continued active participation in community life regardless of age | Elders holding respected positions and actively contributing to decision-making |

Critique of Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory has faced substantial criticism. Empirical evidence frequently contradicts its core assumptions. Many studies demonstrate that forced disengagement can lead to negative psychological and physical health outcomes (e.g., increased depression, reduced life satisfaction). The theory has been accused of being ageist, generalizing the experiences of diverse older populations and failing to account for individual differences in personality, health, and social support.

The theory’s focus on a universal process of withdrawal ignores the agency of older adults and their ability to shape their own aging trajectories.

Comparison with Activity Theory

Activity theory offers a contrasting perspective to disengagement theory.

- Successful Aging: Activity theory emphasizes the importance of social engagement and activity maintenance for successful aging, while disengagement theory suggests that withdrawal is a natural and adaptive process.

- Social Interaction: Activity theory posits that continued social interaction is crucial for well-being and psychological adjustment in older age, whereas disengagement theory views reduced social interaction as a normal part of the aging process.

- Role of Social Networks: Activity theory highlights the significance of strong social networks in promoting positive aging outcomes, while disengagement theory suggests a gradual reduction in social ties is beneficial.

Continuity Theory

Continuity theory acknowledges that individuals strive to maintain consistency in their lives across the lifespan. It challenges disengagement theory by suggesting that individuals do not necessarily disengage from society but rather adapt their social roles and activities to fit their changing circumstances and capabilities. This theory recognizes the importance of individual differences and personal choices in shaping the aging experience, a crucial element missing in the more generalized approach of disengagement theory.

Modern Perspectives on Aging and Social Withdrawal

Current perspectives on aging acknowledge the complex interplay of factors influencing social withdrawal in older adults. Health status, access to social support networks, and personal preferences all play a significant role. While some degree of social withdrawal may be voluntary or even beneficial for some individuals, forced or unwanted social isolation is strongly associated with negative health outcomes.

Modern research emphasizes the importance of promoting active aging, supporting social connections, and ensuring access to resources that enable older adults to maintain their desired level of social engagement.

Core Tenets of Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory, a prominent perspective in gerontology, proposes a natural and mutually beneficial process of withdrawal between aging individuals and society. This theory posits that this gradual disengagement is not necessarily negative, but rather a functional adaptation to the aging process. Understanding its core tenets is crucial to evaluating its validity and impact on our understanding of aging.Disengagement theory rests on several key assumptions.

It suggests that aging is an inevitable process leading to physical and psychological changes that impact an individual’s ability to maintain previous roles and responsibilities. Further, it assumes that society, in turn, anticipates and prepares for this reduced contribution from its older members. This reciprocal process, therefore, is viewed as a natural and even necessary part of the life cycle.

Key Assumptions of Disengagement Theory

The theory’s central assumption is that the decline in social interaction during aging is a natural and inevitable part of the life course. This isn’t necessarily a negative process; instead, it’s seen as a mutual agreement between the individual and society, allowing both to adjust to the changes associated with aging. This involves a reduction in social roles and responsibilities, allowing for a more peaceful and less stressful transition into later life.

Another key assumption is that this mutual withdrawal is beneficial for both the individual and society. For the individual, it reduces stress and allows for increased self-reflection and personal growth. For society, it facilitates a smooth transition of roles and responsibilities to younger generations.

The Reciprocal Nature of Disengagement

Disengagement is not a one-sided process; it’s a dynamic interaction between the aging individual and society. As individuals age, they may experience decreased physical and mental capabilities, leading them to naturally withdraw from certain social roles and activities. Simultaneously, society often adjusts its expectations of older adults, allowing them to gracefully transition into less demanding roles. For example, retirement marks a societal acceptance of decreased work contribution from older adults, while simultaneously providing them with time for personal pursuits.

This reciprocal process is seen as a way to maintain social equilibrium and facilitate the smooth transfer of social roles across generations. The elderly’s decreased participation in the workforce allows younger generations to fill those positions, fostering economic growth and intergenerational support.

Comparison with Other Theories of Aging

Disengagement theory contrasts sharply with other prominent theories of aging, such as activity theory and continuity theory. Activity theory emphasizes the importance of maintaining social activity and engagement in later life to promote well-being. It suggests that remaining active and involved helps older adults maintain their physical and cognitive abilities and fosters a sense of purpose. In contrast, disengagement theory sees a reduction in social interaction as a normal and even desirable aspect of aging.

Continuity theory proposes that individuals strive to maintain consistency in their personality, lifestyle, and social roles throughout their lifespan. It suggests that successful aging involves adapting to changes while preserving a sense of self-continuity. While acknowledging change, it differs from disengagement theory in emphasizing the maintenance of established roles and relationships rather than a gradual withdrawal. These contrasting viewpoints highlight the complexity of the aging process and the diverse experiences of older adults.

The Role of Social Interaction in Disengagement

Disengagement theory posits that reduced social interaction is a natural and even beneficial part of the aging process. However, the impact of this decreased interaction is complex and multifaceted, with both positive and negative consequences for older adults. Understanding this interplay is crucial to evaluating the theory’s validity and implications for the well-being of the elderly.The impact of reduced social interaction on older adults is a significant consideration within the framework of disengagement theory.

While proponents argue that withdrawal allows for introspection and a peaceful transition into later life, critics point to the potential for isolation, loneliness, and a decline in cognitive and physical health. The level of social interaction and its impact varies greatly depending on individual personalities, pre-existing social networks, and access to support systems. A gradual decrease in social engagement may be manageable, even beneficial for some, while a sudden or significant reduction can have detrimental effects.

Impact of Reduced Social Interaction

Reduced social interaction can lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness, impacting mental well-being. This can manifest as depression, anxiety, and a decreased sense of purpose. Furthermore, decreased social stimulation can negatively affect cognitive function, potentially accelerating cognitive decline. Physically, reduced interaction can lead to decreased physical activity and a decline in overall health, as social support networks often play a crucial role in promoting healthy behaviors and access to healthcare.

Conversely, maintaining strong social ties has been shown to correlate with better health outcomes and longevity.

Potential Benefits and Drawbacks of Social Withdrawal

Some argue that social withdrawal in old age can provide a period of reflection and self-discovery, allowing individuals to focus on personal interests and inner peace. This can lead to a greater sense of self-acceptance and contentment. However, the drawbacks are substantial. Social isolation can exacerbate existing health problems and increase the risk of developing new ones.

It can also lead to a decline in self-esteem and a feeling of being disconnected from society. The balance between beneficial withdrawal and harmful isolation is highly individual and context-dependent.

Hypothetical Scenario Illustrating Disengagement, What is the basic idea behind disengagement theory

Imagine Mrs. Eleanor Vance, a 78-year-old woman who recently retired after a long career as a teacher. Initially, she enjoys the freedom, spending time on her hobbies like gardening and painting. However, as time passes, she gradually withdraws from her former social circles. She declines invitations to gatherings, preferring solitude.

While initially this feels peaceful, she begins to experience feelings of loneliness and isolation. Her once vibrant garden becomes neglected, and her paintings gather dust. This scenario illustrates how, even with a seemingly positive initial response to reduced social interaction, disengagement can lead to negative consequences if not managed carefully. This highlights the need for supportive systems and interventions that can help older adults maintain healthy levels of social engagement.

Psychological Aspects of Disengagement

Disengagement theory, while focusing on societal withdrawal, significantly impacts an individual’s psychological well-being. The process of reducing social roles and interactions can lead to a complex interplay of emotional and cognitive changes, affecting self-perception and overall mental health. Understanding these psychological aspects is crucial for developing supportive interventions for older adults.Disengagement can profoundly alter an individual’s self-perception. As individuals relinquish roles that previously defined their identity (e.g., worker, parent, community leader), they may experience a loss of purpose and a diminished sense of self-worth.

This can lead to feelings of inadequacy, loneliness, and even depression. The shift from active participation in society to a more passive role can challenge one’s self-image and create a sense of irrelevance. The resulting decline in self-esteem can be further exacerbated by societal perceptions of aging and the devaluation of older adults’ contributions.

Self-Perception Changes in Disengagement

Reduced social interaction directly impacts self-perception. The loss of regular social contact, feedback, and validation from others can lead to feelings of isolation and decreased self-esteem. For example, a retired teacher who highly valued their role in shaping young minds might struggle with a loss of identity and purpose, leading to feelings of diminished self-worth after retirement. This is particularly true if the individual hasn’t proactively cultivated alternative sources of self-esteem and social connection.

Conversely, individuals who successfully adapt to disengagement by finding new roles and interests may experience a positive shift in self-perception, discovering new aspects of themselves and finding fulfillment in different areas of life.

Psychological Consequences of Social Isolation

Social isolation, a common consequence of disengagement, poses significant risks to mental health. The lack of social interaction can exacerbate existing mental health conditions, like depression and anxiety, and increase the risk of developing new ones. The absence of meaningful connections can lead to feelings of loneliness, hopelessness, and a decreased sense of belonging. Studies have shown a strong correlation between social isolation and increased mortality rates, highlighting the importance of maintaining social connections throughout life.

For instance, an elderly person living alone with limited contact with family or friends may experience a decline in cognitive function and an increased risk of depression due to social isolation.

Coping Mechanisms for Disengagement

Individuals experiencing disengagement employ various coping mechanisms to navigate the psychological challenges. These strategies can be broadly categorized into internal and external coping mechanisms. Internal coping mechanisms involve managing one’s emotions and thoughts, such as through mindfulness practices, introspection, and acceptance of the changing life circumstances. External coping mechanisms involve seeking support from others and engaging in activities that provide a sense of purpose and connection.

Examples of coping mechanisms include:

- Developing new hobbies and interests: Engaging in activities that provide a sense of accomplishment and enjoyment, such as gardening, painting, or joining a book club.

- Maintaining strong social connections: Nurturing existing relationships and actively seeking out new social interactions through volunteering, attending community events, or joining social groups.

- Seeking professional support: Consulting a therapist or counselor to address feelings of depression, anxiety, or loneliness.

- Practicing mindfulness and self-compassion: Developing techniques to manage stress, cultivate self-awareness, and treat oneself with kindness and understanding.

- Focusing on personal growth: Engaging in activities that promote personal development, such as learning a new language, taking online courses, or pursuing spiritual practices.

Physical Health and Disengagement

The relationship between physical health and social engagement in later life is complex and bidirectional. While disengagement theory suggests a natural withdrawal from social roles, declining physical health often acts as a significant contributing factor, creating a feedback loop where poor health limits social participation, and reduced social interaction potentially exacerbates health decline. This section explores this interplay.Declining physical health can significantly contribute to disengagement.

Chronic illnesses like arthritis, heart disease, or dementia can limit mobility, energy levels, and cognitive function, making social participation more challenging. Pain, fatigue, and decreased dexterity can impede activities like attending social events, volunteering, or even engaging in simple conversations. The resulting social isolation can further negatively impact mental and physical well-being, creating a vicious cycle. For instance, an individual with severe arthritis might find it difficult to drive to a senior center, leading to decreased social interaction and potentially accelerating feelings of loneliness and depression.

The Correlation Between Physical Health and Social Engagement

Numerous studies demonstrate a strong correlation between physical health and social engagement in older adults. Individuals with better physical health tend to be more socially active, participating in more social activities and maintaining stronger social networks. Conversely, those with poorer physical health often experience reduced social participation and increased social isolation. This isn’t simply a matter of correlation, however; research suggests a causal link, where social engagement can positively impact physical health outcomes.

Health Outcomes: Engaged vs. Disengaged Older Adults

| Health Outcome | Engaged Older Adults | Disengaged Older Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Function | Generally higher levels of physical activity and better mobility; lower risk of falls. | Reduced physical activity, increased risk of falls and functional decline; more likely to experience limitations in daily activities. |

| Cognitive Function | Slower cognitive decline; reduced risk of dementia and cognitive impairment. | Accelerated cognitive decline; higher risk of dementia and cognitive impairment; increased prevalence of depression and anxiety. |

| Mental Health | Lower rates of depression, anxiety, and loneliness; higher levels of life satisfaction and well-being. | Higher rates of depression, anxiety, and loneliness; lower levels of life satisfaction and well-being; increased risk of suicide. |

| Mortality | Lower mortality rates; increased longevity. | Higher mortality rates; reduced life expectancy. |

Social and Cultural Influences on Disengagement

Disengagement theory, while initially presented as a universal process, is significantly shaped by the social and cultural contexts in which individuals age. Understanding these influences is crucial for developing effective interventions to promote healthy aging and social participation. Cultural norms, societal structures, and technological advancements all play a role in determining how individuals disengage from social roles and activities as they age.

Cultural Factors Influencing Disengagement Rates

Several cultural factors significantly influence the rate of disengagement. Collectivist cultures, prioritizing group harmony and interdependence, may exhibit different disengagement patterns compared to individualistic cultures that emphasize personal autonomy and self-reliance. Religious beliefs and practices also play a crucial role, shaping attitudes toward aging and influencing social participation in later life. Finally, a society’s Power Distance Index (PDI) and level of technological advancement further impact disengagement rates.

Collectivist vs. Individualist Cultures and Disengagement

In collectivist societies, such as many in East Asia, maintaining strong family ties and community involvement is highly valued. Older adults often remain integrated into family structures and continue contributing to the community, leading to lower rates of disengagement. Conversely, individualistic cultures, like many Western societies, emphasize individual achievement and independence. Retirement may be viewed as a time for personal pursuits, potentially leading to greater social withdrawal in some cases.

While precise comparative data on disengagement rates across these cultural types is limited, studies on retirement ages offer some insight. For example, the average retirement age tends to be lower in many European countries (considered more collectivist in some aspects) than in the United States, which might suggest a different approach to disengagement. However, this is a complex issue with multiple contributing factors beyond just collectivism/individualism.

Religious Beliefs and Practices and Disengagement

Religious beliefs and practices significantly impact attitudes toward aging and social participation. Religions that emphasize community and intergenerational support may foster greater social engagement among older adults. For instance, in many religious communities, older members often hold respected positions and continue to actively participate in religious activities. Conversely, religions that emphasize individual spiritual practices may lead to more solitary lifestyles in old age.

Specific examples vary greatly; some religions have robust support systems for the elderly while others may place less emphasis on communal care.

Power Distance Index (PDI) and Disengagement

Societies with high PDI scores, characterized by hierarchical structures and acceptance of inequality, may exhibit different disengagement patterns compared to low-PDI societies. In high-PDI societies, older adults may readily accept a reduced role in society due to established hierarchies. Conversely, low-PDI societies, emphasizing equality and participation, may encourage continued engagement in social roles among older adults. Research directly linking PDI to disengagement rates is scarce, requiring further investigation.

Technological Advancement and Disengagement

The rapid advancement of technology presents both opportunities and challenges regarding social engagement among older adults. Increased access to technology, such as the internet and social media, can enhance social connections and reduce feelings of isolation. However, the digital divide, where some older adults lack access to or proficiency with technology, can exacerbate social isolation and contribute to disengagement.

Disengagement theory posits that older adults gradually withdraw from social roles and activities, leading to a decreased interaction with society. Understanding this process can be enhanced by considering the individual’s motivational orientation, as explained by what is the regulatory focus theory. A person’s focus on either prevention or promotion goals might influence the nature and extent of their disengagement, highlighting the interplay between individual psychology and societal expectations in aging.

This disparity is particularly pronounced in less developed countries with lower rates of technology adoption.

Comparative Analysis of Disengagement Patterns Across Cultures

| Culture/Society | Disengagement Rate (if available) | Key Factors Contributing to Disengagement | Social Support Systems | Government Policies Related to Aging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Data unavailable, but generally low rate of formal retirement. | Emphasis on family support, changing social norms | Strong family ties, community-based support networks | Policies promoting longevity and active aging |

| United States | Data unavailable, but varies widely based on socioeconomic factors. | Individualistic culture, changing family structures | Varying levels of family and community support, formal care systems | Mix of policies, some promoting early retirement, others encouraging active aging |

| Nigeria | Data unavailable, high rates of informal caregiving. | Traditional family structures, limited formal support systems | Primarily family-based care, religious institutions | Limited government support for aging population |

| Sweden | Data unavailable, relatively high level of social engagement in later life. | Strong social safety net, emphasis on social welfare | Extensive social welfare system, robust community programs | Policies promoting active aging and social inclusion |

Note: The lack of readily available quantitative data on disengagement rates across cultures highlights a significant gap in research. Further investigation is crucial to understand the nuances of disengagement across diverse populations. The examples provided are based on general observations and require further nuanced study.

Social Policies Influencing Disengagement

Social policies play a significant role in either encouraging or discouraging disengagement. Policies can either incentivize withdrawal from the workforce or actively promote continued engagement in society.

Policies that Encourage Disengagement

- Early retirement incentives: While offering financial benefits, these may lead to premature withdrawal from the workforce and reduced social interaction.

- Limited access to affordable elder care: The lack of affordable and accessible care services can force older adults to rely on family members, potentially reducing their social participation outside the home.

- Inadequate public transportation: Poor public transport can limit mobility and access to social activities, contributing to isolation and disengagement.

Policies that Discourage Disengagement

- Active aging programs: These programs promote physical and cognitive health, and social engagement among older adults, improving their quality of life and reducing isolation.

- Senior centers and community facilities: These provide opportunities for social interaction, recreation, and learning, fostering a sense of belonging and purpose.

- Subsidized transportation: Affordable and accessible transportation options enable older adults to participate in community activities and maintain social connections.

Criticisms of Disengagement Theory

Disengagement theory, while influential in its time, has faced significant criticism due to its limited scope and questionable assumptions about the aging process. Many researchers argue that it presents an overly simplistic and potentially negative view of aging, neglecting the diversity of experiences and the active roles many older adults continue to play in society. The theory’s predictive power has also been challenged by substantial empirical evidence.

Major Criticisms of Disengagement Theory

The primary criticisms center on the theory’s lack of universality. It fails to account for the wide variations in individual experiences of aging, ignoring factors such as socioeconomic status, health, personality, and cultural context. For instance, the theory suggests a natural decline in social interaction, yet many older adults maintain robust social networks and actively seek out new connections.

Furthermore, the assumption of mutual withdrawal between older adults and society is not consistently observed across cultures or even within specific societies. The theory also lacks strong empirical support, with many studies demonstrating that active engagement, rather than disengagement, is often associated with better physical and mental health in later life.

Alternative Theories of Aging

Several alternative theories challenge the core tenets of disengagement theory. Activity theory, for example, proposes that maintaining high levels of social interaction and activity is crucial for successful aging. This theory emphasizes the importance of social roles and engagement in preserving well-being and preventing social isolation. Continuity theory suggests that individuals maintain consistent patterns of behavior and personality throughout their lives, adapting to changes in their physical and social environments.

This contrasts sharply with disengagement theory’s prediction of significant behavioral shifts in later life. Lastly, selective optimization with compensation theory highlights the adaptive strategies older adults employ to maintain functioning in the face of age-related declines. This focuses on selectively choosing activities that are most meaningful and optimizing performance through practice and compensation for losses.

Research Contradicting Disengagement Theory

Numerous studies have yielded results inconsistent with disengagement theory’s predictions. Longitudinal studies tracking individuals over extended periods have shown that those who remain socially active and engaged tend to experience better cognitive function, lower rates of depression, and increased longevity. For example, research on the impact of volunteering on older adults’ well-being consistently demonstrates positive correlations between volunteering and improved mental and physical health, challenging the idea that withdrawal from social roles leads to better adaptation.

Similarly, studies examining the social networks of older adults frequently reveal extensive and diverse connections, contradicting the notion of a natural decline in social interaction. These findings highlight the importance of social engagement and active participation in maintaining a high quality of life in later years.

Modern Perspectives on Disengagement

Disengagement theory, while influential in its time, has faced significant revisions in light of contemporary research. Modern perspectives acknowledge the theory’s limitations and emphasize the complexity of the aging process, highlighting individual agency and the diverse ways individuals navigate later life. The focus has shifted from a predominantly negative view of disengagement to a more nuanced understanding of its role, alongside other factors, in shaping successful aging.Contemporary research has largely rejected the idea of inevitable and universal disengagement as a normative part of aging.

Instead, it recognizes that the degree of social interaction and activity varies greatly among older adults, influenced by factors like health, personality, social support networks, and personal preferences. Studies show that many older adults maintain active social lives and continue to engage meaningfully in various activities throughout their later years, challenging the core tenets of the original disengagement theory.

The emphasis now lies on understanding the diverse pathways to aging, rather than assuming a single, predictable trajectory.

Successful Aging and Disengagement

Successful aging is defined not by the absence of disengagement, but by the ability to maintain a sense of purpose, well-being, and social connectedness despite age-related changes. This concept recognizes that some degree of withdrawal from certain roles and activities might be a natural and even positive part of the aging process for some individuals, allowing them to focus on activities that bring them greater satisfaction.

However, successful aging is not solely dependent on continued high levels of social engagement. It emphasizes adaptability, resilience, and the ability to find meaning and fulfillment in life, regardless of the level of social interaction. For example, an individual might choose to reduce their work hours or retire but remain actively involved in volunteering, hobbies, or family life, representing a selective disengagement rather than a complete withdrawal.

Individual Agency in the Aging Process

Modern perspectives strongly emphasize the role of individual agency in shaping the aging experience. Older adults are not passive recipients of age-related changes but active agents who make choices about their lives and how they engage with the world around them. This agency manifests in decisions regarding social participation, lifestyle choices, and the pursuit of personal goals. For instance, an individual’s personality, prior life experiences, and personal values influence their level of social interaction and their adaptation to the challenges of aging.

Recognizing this agency challenges the deterministic view inherent in the original disengagement theory, highlighting the active role individuals play in shaping their own aging trajectories. Instead of viewing disengagement as a predetermined outcome, contemporary research investigates the factors that influence individuals’ choices and the diverse ways they negotiate the changes associated with aging.

The Impact of Technology on Disengagement

Technology’s role in the lives of older adults is increasingly significant, impacting their social connections and overall well-being. This section explores how technology can both mitigate and exacerbate disengagement, focusing on its influence on social interaction, access to support, and the potential for both positive and negative consequences.

Technology’s Correlation with Social Connectedness in Older Adults

A study analyzing technology usage among individuals aged 65 and older revealed a positive correlation between the frequency of email, video calls, and messaging app usage and self-reported levels of social connectedness. This correlation was statistically significant even after controlling for pre-existing health conditions and socioeconomic status. A scatter plot illustrating this relationship would show a clear upward trend, with increased technology use associated with higher reported social connectedness scores.

A correlation matrix would further demonstrate the strength of the relationship between each technology type and social connectedness. The data suggests that regular engagement with these technologies contributes significantly to maintaining social ties in later life.

Comparing the Effectiveness of Different Technological Tools for Social Interaction

Different technological tools offer varying levels of effectiveness in fostering meaningful social interactions. The following table compares video conferencing platforms and social media platforms, considering their impact on social connection for older adults living independently versus those in assisted living facilities.

| Feature | Video Conferencing (e.g., Zoom, Skype) | Social Media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | Impact (Independent Living) | Impact (Assisted Living) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time Interaction | High | Variable | Stronger social connection | Improved communication with family |

| Ease of Use | Moderate | Variable (depending on platform) | Requires some tech literacy | May require staff assistance |

| Depth of Connection | High | Moderate | More intimate interactions | Facilitates group activities |

| Accessibility | Requires device and internet access | Similar accessibility requirements | Can be a barrier for some | Often provided by facility |

Digital Literacy and Technology Adoption Among Older Adults

Digital literacy plays a crucial role in determining how effectively older adults utilize technology for social connection. Individuals with higher digital literacy skills are more likely to adopt and successfully use various technologies. However, a significant portion of the older adult population lacks sufficient digital literacy skills, hindering their ability to benefit from technology. Increased accessibility of training resources and support systems, tailored to the specific needs of older adults, is essential to bridge this digital divide and ensure equitable access to the benefits of technology.

Technology’s Potential to Mitigate Social Isolation

Technology offers significant potential to mitigate social isolation among older adults. Online communities, virtual support groups, and remote healthcare services provide opportunities for connection and access to support that may be geographically or physically challenging to obtain otherwise. For example, online support groups for individuals with chronic illnesses allow for peer-to-peer support and shared experiences, reducing feelings of isolation.

Telemedicine provides access to healthcare professionals without the need for travel, improving health outcomes and reducing social isolation.

Excessive Technology Use and its Potential Negative Impacts

While technology offers numerous benefits, excessive use can negatively impact mental well-being. Excessive social media consumption can lead to feelings of loneliness, anxiety, and social comparison, potentially exacerbating disengagement. Studies have shown a correlation between excessive social media use and increased feelings of inadequacy and depression among older adults. Similarly, excessive online gaming can lead to social isolation and neglect of real-life relationships.

The Potential for a “Digital Divide” Among Older Adults

The “digital divide” can exacerbate feelings of exclusion and further disengagement among older adults. Factors like access to technology, digital literacy, and affordability contribute to this disparity. Older adults with limited financial resources may not be able to afford the necessary technology or internet access. Those lacking digital literacy skills may struggle to use technology effectively, leading to frustration and feelings of inadequacy.

This unequal access reinforces social isolation and limits the benefits technology can offer.

Comparing the Impact of Different Social Media Platforms on Older Adults

Different social media platforms cater to diverse user demographics and offer varying levels of ease of use and interaction. Facebook, with its user-friendly interface and large user base, is widely used by older adults. Twitter, with its emphasis on brevity, may be less appealing to those less comfortable with technology. Instagram’s visual focus may appeal to some, while others may find it less engaging.

The nature of interactions on each platform also differs, influencing the overall impact on social lives.

| Platform | Ease of Use | User Demographics | Nature of Interactions | Impact on Social Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Wide range, including older adults | Varied; sharing updates, connecting with friends and family | Positive: increased connection, sharing life events | |

| Moderate | Younger demographic, but growing older adult usage | Short, quick updates, public discussions | Positive: access to information, engagement in public discourse; Negative: potential for negativity | |

| Moderate | Skews younger, but growing older adult usage | Visual sharing, following influencers | Positive: visual storytelling, connecting through shared interests; Negative: potential for unrealistic comparisons |

Social Media and Older Adults with Cognitive Impairments

Social media use presents both benefits and drawbacks for older adults with cognitive impairments. While it can facilitate communication and connection, it also carries risks. The potential for misinformation, online harassment, and the impact on mental well-being must be carefully considered. The ease of use and accessibility of the platform, alongside appropriate supervision and support, are crucial factors in determining the positive or negative impact.

Social Media’s Role in Facilitating Intergenerational Connections

Social media platforms can facilitate intergenerational connections between older and younger generations. Initiatives that encourage interaction between age groups, such as online storytelling projects or virtual mentoring programs, can be particularly beneficial. These platforms allow for the sharing of experiences, perspectives, and knowledge across generations, fostering mutual understanding and respect.

Ethical Considerations and Future Research Directions

Ethical considerations regarding data privacy, informed consent, and potential biases in research methodologies are crucial. Future research should focus on the effectiveness of specific technological interventions designed to improve social engagement among older adults. Investigating the role of policy in promoting digital inclusion is also essential to ensure equitable access to the benefits of technology for all older adults.

Disengagement and Social Support Networks

Maintaining strong social connections is crucial for older adults, especially as they age and may experience cognitive decline. Social support networks act as a buffer against the negative impacts of disengagement, offering emotional, physical, and cognitive benefits. This section explores the multifaceted relationship between social support and successful aging in the context of disengagement.

The Importance of Social Support Networks in Mitigating Disengagement

Robust social support networks play a vital role in mitigating the negative consequences of disengagement among older adults (65+) experiencing age-related cognitive decline. These networks provide a crucial sense of belonging and purpose, combating the isolation and loneliness often associated with aging and cognitive changes.

Emotional Well-being

Strong social connections significantly reduce the risk of depression, anxiety, and feelings of loneliness. Regular interaction with friends, family, and community members provides emotional reassurance, validation, and a sense of purpose. For example, participation in a book club can offer intellectual stimulation and social interaction, combating feelings of isolation, while regular phone calls from family members can provide emotional support and reduce feelings of loneliness.

Physical Health

Numerous studies demonstrate a strong correlation between strong social support and improved physical health outcomes. Individuals with extensive social networks tend to exhibit lower rates of cardiovascular disease, reduced risk of falls, and faster recovery from illness. For example, a study published in the journal “Social Science & Medicine” found that individuals with strong social ties had a significantly lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

The supportive nature of these relationships provides a sense of security and reduces stress, positively impacting the body’s physiological responses.

Cognitive Function

Social interaction stimulates cognitive function, enhancing memory, attention, and processing speed. Engaging in conversations, participating in group activities, and learning new things alongside others promotes neuroplasticity and maintains cognitive reserve. Studies have shown that individuals who actively participate in social activities exhibit better cognitive performance compared to those who are socially isolated. The constant stimulation provided by social interaction helps to keep the brain active and engaged, slowing down the rate of cognitive decline.

Types of Social Support Networks and Their Effectiveness

The effectiveness of different social support networks varies depending on an individual’s mobility level.

| Type of Support Network | Description | Effectiveness for High Mobility | Effectiveness for Moderate Mobility | Effectiveness for Low Mobility | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person social groups | Regular meetings with peers for shared activities. | High | Moderate | Low (requires accessible locations) | Book clubs, walking groups, volunteer organizations |

| Online social networks | Connecting with others through virtual platforms. | Moderate | Moderate | High | Social media groups, online gaming communities, video calls with family |

| Family and close friends | Support from immediate social circle. | High | Moderate | High (if geographically close and willing to provide support) | Regular visits, phone calls, assistance with daily tasks |

| Professional support services | Paid services providing companionship or assistance. | Moderate | Moderate | High | Home care aides, senior centers, adult day care |

Strategies for Strengthening Social Support Networks

Strengthening social support networks requires a multi-pronged approach tailored to the individual’s circumstances and resources.

High Accessibility, Low Cost

- Strategy 1: Community Centers and Senior Centers: These centers offer a variety of activities and social events, fostering interaction and building connections. Implementation involves attending regularly scheduled events and programs.

- Strategy 2: Volunteer Work: Engaging in volunteer activities provides a sense of purpose and connects individuals with others who share similar interests. Implementation involves identifying local organizations and committing to a regular schedule.

Moderate Accessibility, Moderate Cost

- Strategy 3: Organized Social Groups: Joining groups focused on hobbies or interests (e.g., hiking clubs, art classes) facilitates social interaction and shared experiences. Implementation involves researching and joining relevant groups.

- Strategy 4: Subscription-based online services: Platforms offering virtual social interaction, educational opportunities, or companionship can be beneficial. Implementation involves subscribing to a chosen service and actively engaging with its features.

Low Accessibility, High Cost

- Strategy 5: Professional Companionship Services: Paid companions can provide regular social interaction for individuals with limited social networks. Implementation involves researching and hiring a reputable service.

- Strategy 6: In-home care services with social components: Caregivers who provide not only physical assistance but also social interaction and companionship. Implementation involves assessing needs and hiring qualified in-home care providers.

Comparative Analysis of Intervention Programs

Various intervention programs aim to strengthen social support networks for older adults. Their effectiveness varies depending on design and implementation.

| Intervention Program | Target Population | Program Design | Key Outcomes | Long-Term Impact | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational Programs | Older adults and younger generations | Pairing older adults with children or young adults for shared activities. | Increased social interaction, reduced loneliness, improved mood. | Sustained social connections for some participants. | Requires careful matching and supervision; not suitable for all older adults. |

| Social Skills Training Groups | Older adults with social anxiety or isolation. | Structured group sessions focusing on communication and social interaction skills. | Improved communication skills, increased confidence in social situations. | Mixed results; some maintain improvements, others revert to previous patterns. | Requires commitment and participation; may not be effective for all individuals. |

| Community-Based Support Groups | Older adults with shared health conditions or life experiences. | Regular meetings for mutual support and shared experiences. | Reduced feelings of isolation, increased sense of belonging, improved coping skills. | Can provide long-term support and social connection. | Accessibility can be a barrier; requires strong group leadership. |

Ethical Considerations in Designing and Implementing Interventions

Designing and implementing interventions to improve social support networks requires careful consideration of ethical implications. Respect for autonomy is paramount; older adults should have the right to choose whether or not to participate in any program and retain control over their social interactions. Maintaining privacy is crucial; personal information should be handled responsibly and securely. Coercion should be avoided at all costs; participation must be voluntary and based on informed consent. Programs should be designed to empower individuals rather than control them, fostering independence and self-determination while addressing their social needs. Regular evaluation and feedback mechanisms are essential to ensure programs are ethical and effective.

Measuring Disengagement

Accurately measuring disengagement in older adults presents significant methodological challenges. This requires a multifaceted approach incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methods to capture the complex interplay of social, emotional, and physical factors contributing to disengagement. The following sections detail the methods, challenges, and a hypothetical questionnaire designed to assess disengagement comprehensively.

Detailed Methods for Measuring Disengagement in Older Adults

Several established scales and indices can be employed to quantify aspects of disengagement. Qualitative data collection further enriches our understanding of the lived experience. The combination of these methods provides a more nuanced perspective than any single approach.

- Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS): This scale assesses the size and strength of an individual’s social network. Strengths include ease of administration and broad applicability. Limitations include its focus on network size rather than quality of relationships, and it may not fully capture emotional aspects of disengagement.

- UCLA Loneliness Scale: This scale measures the subjective experience of loneliness. Its strengths lie in its direct assessment of a key aspect of disengagement. However, loneliness doesn’t encompass the full spectrum of disengagement; individuals may be socially isolated but not necessarily feel lonely.

- Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): While primarily assessing depression, depressive symptoms often correlate with disengagement. Strengths include established validity and reliability in older populations. Limitations include that depression is not synonymous with disengagement; some individuals may be disengaged without experiencing depression.

An operational definition of “disengagement” in this context will be: a reduction in social participation, emotional investment, and cognitive engagement, manifested through decreased social interactions, reported feelings of loneliness or isolation, reduced participation in stimulating activities, and decreased sense of purpose. Behavioral indicators will include frequency of social interactions, participation in activities, and level of physical activity.

Emotional indicators will include reported feelings of loneliness, isolation, and emotional well-being. Social indicators will include the size and quality of social networks and reported social support.Qualitative data will be gathered using semi-structured interviews. Interview questions will explore participants’ experiences of social interaction, feelings of loneliness, sense of purpose, and levels of engagement in various activities. For example, questions might include: “Can you describe a typical day for you?”, “How would you describe your relationships with family and friends?”, and “What activities do you engage in that give you a sense of satisfaction or purpose?”.Triangulation of data will involve comparing and contrasting findings from quantitative (LSNS, UCLA Loneliness Scale, GDS scores) and qualitative (interview transcripts) data sources.

This allows for a cross-validation of results and a richer, more comprehensive understanding of disengagement.

Challenges in Accurately Measuring Disengagement

Measuring disengagement accurately faces several inherent challenges, primarily due to the subjective nature of the phenomenon and the influence of external factors.Self-reported measures are susceptible to social desirability bias (respondents portraying themselves more positively than is accurate) and recall bias (inaccurate recall of past behaviors or feelings). Strategies to mitigate these include using multiple measures, including objective indicators (e.g., attendance records at social events), and employing techniques to encourage honest responses (e.g., assuring confidentiality).Cultural norms significantly influence the interpretation and measurement of disengagement.

For instance, a preference for solitude in some cultures might be misinterpreted as disengagement. Similarly, socioeconomic status and living arrangements (e.g., living alone versus in a community) affect engagement levels. Careful consideration of these contextual factors is crucial.Establishing a baseline for engagement is challenging because the level of engagement varies across individuals and changes with age. Differentiating normal aging processes (e.g., decreased physical activity) from pathological disengagement requires a longitudinal approach and consideration of multiple indicators.Disengagement is multidimensional.

The chosen methods address each dimension by employing a range of scales and qualitative methods to assess social, emotional, cognitive, and physical aspects of engagement.

Hypothetical Questionnaire to Assess Disengagement

The following table presents a hypothetical questionnaire using a Likert scale to assess disengagement in older adults.

| Question Number | Question Text | Response Scale (1-5) | Response Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | How often do you participate in social activities outside your home? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

| 2 | How satisfied are you with your current level of social interaction? | 1-5 (Very Dissatisfied to Very Satisfied) | Likert |

| 3 | How often do you feel lonely or isolated? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

| 4 | How would you rate your overall emotional well-being? | 1-5 (Poor to Excellent) | Likert |

| 5 | How often do you engage in mentally stimulating activities (e.g., reading, puzzles)? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

| 6 | How would you rate your physical health? | 1-5 (Poor to Excellent) | Likert |

| 7 | How often do you feel a sense of purpose or meaning in your life? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

| 8 | How often do you feel in control of your life? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

| 9 | How satisfied are you with your current living situation? | 1-5 (Very Dissatisfied to Very Satisfied) | Likert |

| 10 | How often do you interact with family and friends? | 1-5 (Never to Daily) | Likert |

Data Analysis Plan

Data analysis will involve descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) to summarize the questionnaire responses. Inferential statistics (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, correlation analysis) will be used to examine relationships between different measures of disengagement and other variables (e.g., age, health status, social network size). Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns in participants’ experiences.

Case Studies of Disengagement: What Is The Basic Idea Behind Disengagement Theory

This section presents three hypothetical case studies illustrating disengagement in different life contexts: workplace, education, and social settings. Each case study provides a detailed description, analyzes contributing factors, suggests potential interventions, and explores a counterfactual scenario. These examples aim to highlight the multifaceted nature of disengagement and the importance of understanding its underlying causes to develop effective interventions.

Case Study 1: Workplace Disengagement (Burnout)

Detailed Description: Sarah, a 38-year-old marketing manager at a fast-paced tech startup, has been experiencing increasing disengagement from her work for the past six months. Initially a highly motivated and productive employee, Sarah consistently exceeded expectations in her first three years with the company. However, a recent restructuring led to increased workload, longer hours, and a significant reduction in support staff.

She now regularly misses deadlines, makes more errors, and exhibits a noticeable lack of enthusiasm during team meetings. She frequently complains of exhaustion, both physically and mentally, and has begun arriving late and leaving early. Her once meticulous work now shows signs of carelessness, and she actively avoids taking on new projects. Sarah’s personal life has also suffered.

She reports feeling irritable and withdrawn from her family and friends, often canceling social engagements due to fatigue. She describes a sense of hopelessness and cynicism towards her work, expressing feelings of being undervalued and overwhelmed. She feels a growing disconnect between her personal values and her current role, leading to a loss of meaning and purpose in her work.

Disengagement theory posits that aging involves a gradual withdrawal from social roles and activities. Understanding this process can be illuminated by considering the contrasting model of usage-based pricing, as exemplified by software examined in detail at what software is sold on usage-based theory. Conversely, disengagement theory suggests a natural decline in activity, unlike the potentially constant engagement implied by pay-per-use software models.

Contributing Factors:

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Explanation & Evidence from Case Study | Impact on Disengagement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Factors | Perfectionism | Sarah’s history of striving for perfection likely contributed to her feeling overwhelmed by the increased workload and pressure. | Increased stress and feelings of inadequacy, leading to avoidance and reduced productivity. |

| Environmental Factors | Increased workload and reduced support | The restructuring led to a significant increase in Sarah’s responsibilities with less support from colleagues. | Overwhelm, burnout, and a sense of being unsupported. |

| Situational Factors | Lack of work-life balance | The increased workload led to long hours and a lack of time for personal activities, exacerbating stress and fatigue. | Physical and emotional exhaustion, leading to decreased motivation and engagement. |

Potential Interventions:

- Intervention: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) focused on identifying and challenging negative thought patterns contributing to feelings of helplessness and lack of motivation.

Rationale: CBT is effective in addressing cognitive distortions and developing coping mechanisms for managing stress and improving self-efficacy.

Anticipated Outcomes: Improved self-esteem, increased motivation, and a renewed sense of purpose. - Intervention: Workplace adjustments, including a reduction in workload, additional support staff, and flexible working arrangements.

Rationale: Addressing the environmental factors contributing to Sarah’s burnout can alleviate stress and improve her well-being.

Anticipated Outcomes: Reduced stress levels, improved work-life balance, and increased job satisfaction. - Intervention: Stress management techniques such as mindfulness meditation and yoga.

Rationale: These techniques can help Sarah manage stress, improve emotional regulation, and promote relaxation.

Anticipated Outcomes: Reduced anxiety, improved sleep quality, and increased resilience to stress.

Counterfactual Analysis: Had these interventions been implemented earlier, Sarah might have avoided the significant decline in her well-being and professional performance. Early identification of burnout symptoms and proactive intervention could have prevented the development of chronic stress and maintained her engagement and productivity.

Case Study 2: Educational Disengagement (Student Apathy)

Detailed Description: Mark, a 17-year-old high school student, has shown a significant decline in his academic performance and engagement over the past year. Once an enthusiastic learner, Mark now consistently misses classes, fails to complete assignments, and shows little interest in his studies. He spends most of his time playing video games and socializing online, neglecting his schoolwork. His teachers report a lack of participation in class discussions and a general apathy towards learning.

Mark expresses feelings of boredom and frustration with the curriculum, claiming it is irrelevant and uninteresting. He also reports feeling overwhelmed by the pressure to succeed academically and socially, leading to feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem. He has withdrawn from his friends and family, preferring to spend his time alone in his room.

Contributing Factors:

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Explanation & Evidence from Case Study | Impact on Disengagement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Factors | Low self-esteem | Mark’s feelings of inadequacy and lack of confidence contribute to his avoidance of challenging tasks. | Reduced motivation and avoidance of academic responsibilities. |

| Environmental Factors | Unengaging curriculum | Mark finds the school curriculum boring and irrelevant to his interests. | Lack of interest and motivation to learn. |

| Situational Factors | Academic pressure and social anxiety | The pressure to succeed academically and the fear of social judgment contribute to his stress and anxiety. | Withdrawal from school and social activities. |

Potential Interventions:

- Intervention: Individual counseling to address Mark’s low self-esteem and anxiety.

Rationale: Counseling can help Mark develop coping mechanisms for managing stress and build confidence in his abilities.

Anticipated Outcomes: Improved self-esteem, reduced anxiety, and increased motivation to participate in school. - Intervention: Educational adjustments, such as individualized learning plans and access to alternative learning resources tailored to his interests.

Rationale: Addressing Mark’s boredom and frustration with the current curriculum can increase his engagement.

Anticipated Outcomes: Increased interest in learning and improved academic performance. - Intervention: Peer support groups to help him connect with other students and build social connections.

Rationale: Social support can help alleviate feelings of isolation and improve his overall well-being.

Anticipated Outcomes: Reduced social anxiety and improved social skills.

Counterfactual Analysis: Early intervention could have prevented Mark’s disengagement from school and its negative impact on his academic progress and overall well-being. Addressing his underlying emotional issues and tailoring his learning experience to his interests could have maintained his enthusiasm for learning.

Case Study 3: Social Disengagement (Social Isolation)

Detailed Description: Eleanor, a 72-year-old widow, has become increasingly socially isolated since the death of her husband two years ago. She lives alone in a quiet suburban neighborhood and has limited contact with her children and grandchildren, who live several states away. Eleanor rarely leaves her home, preferring to spend her days watching television and reading. She has withdrawn from her previous social activities, including her book club and weekly bridge game.

She reports feeling lonely and depressed, often expressing feelings of sadness and hopelessness. She has difficulty making new friends and avoids social interactions, fearing rejection or further loss. Her physical health has also deteriorated, with reports of increased fatigue and decreased mobility.

Contributing Factors:

| Factor Category | Specific Factor | Explanation & Evidence from Case Study | Impact on Disengagement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Factors | Grief and depression | Eleanor’s grief over the loss of her husband has led to depression and a withdrawal from social life. | Reduced motivation to engage in social activities and a general feeling of hopelessness. |

| Environmental Factors | Geographic isolation | Eleanor lives alone and has limited contact with family and friends. | Lack of social interaction and support. |

| Situational Factors | Loss of spouse | The death of her husband has significantly impacted her social life and emotional well-being. | Increased loneliness, depression, and withdrawal from social activities. |

Potential Interventions:

- Intervention: Grief counseling to help Eleanor process her grief and adjust to her new life without her husband.

Rationale: Addressing the underlying emotional distress can help her regain a sense of purpose and motivation to engage in social activities.

Anticipated Outcomes: Improved emotional regulation, reduced feelings of loneliness and depression, and increased motivation to reconnect with others. - Intervention: Social support groups for widows to provide a sense of community and shared experience.

Rationale: Connecting with others who have experienced similar losses can provide emotional support and reduce feelings of isolation.

Anticipated Outcomes: Increased social interaction, reduced loneliness, and improved overall well-being. - Intervention: Home-based services such as meal delivery and transportation assistance to facilitate social engagement.

Rationale: Addressing practical barriers to social participation can make it easier for Eleanor to connect with others.

Anticipated Outcomes: Increased opportunities for social interaction and reduced feelings of isolation.

Counterfactual Analysis: Early intervention, including grief counseling and access to social support groups, could have mitigated Eleanor’s social isolation and its negative consequences on her mental and physical health. Providing support and facilitating social connection could have improved her quality of life significantly.

Implications for Social Policy

Disengagement theory, while criticized, offers valuable insights into the aging process and its societal implications. Understanding the potential for social withdrawal in later life necessitates the development of proactive social policies aimed at promoting engagement and well-being among older adults. Failure to address this can lead to increased social isolation, decreased health outcomes, and a greater burden on healthcare systems.The implications of disengagement theory for social policy are multifaceted, impacting resource allocation, program design, and the overall approach to supporting older adults.

A key consideration is the need to shift from a primarily medical model of aging to one that prioritizes social participation and active aging. This requires a comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to disengagement and the development of targeted interventions.

Governmental Support and Prevention of Disengagement

Governments play a crucial role in mitigating the negative effects of disengagement. This involves investing in community-based programs that foster social interaction and provide opportunities for older adults to remain active and engaged. Such programs could include senior centers offering diverse activities, transportation services to facilitate access to social events, and initiatives promoting intergenerational connections. Furthermore, policies supporting affordable housing in vibrant communities, alongside accessible and affordable healthcare, are essential in preventing social isolation.

Examples of successful government initiatives include the Meals on Wheels program (which combats social isolation alongside providing nutritional support) and various community grant programs that fund social activities for seniors.

Policy Proposal: Promoting Social Engagement Among Older Adults

This policy proposal focuses on creating “Intergenerational Engagement Hubs” within existing community centers or through the establishment of new facilities. These hubs would serve as central locations offering a diverse range of activities designed to foster interaction between older adults and younger generations.The core components of the proposal are:

- Mentorship Programs: Pairing older adults with younger individuals for skill-sharing and mutual learning (e.g., technology tutoring from young people, storytelling and life experience sharing from seniors).

- Shared Activities: Organizing group activities that appeal to both age groups, such as gardening clubs, arts and crafts workshops, or volunteer projects.

- Technology Training and Support: Providing digital literacy training for older adults, bridging the digital divide and enabling participation in online communities and social activities.

- Transportation Assistance: Ensuring accessible and affordable transportation to and from the hubs, overcoming mobility barriers.

- Accessibility and Inclusivity: Designing the hubs to be accessible to individuals with diverse physical and cognitive abilities.

This multi-pronged approach aims to counteract the potential for disengagement by providing structured opportunities for social interaction, skill development, and community involvement, ultimately contributing to a more vibrant and inclusive society for all ages. The success of this initiative would be measured through quantitative data such as increased participation rates in activities and qualitative data such as participant feedback on their experiences and perceived well-being.

Ethical Considerations of Disengagement

Disengagement theory, while offering insights into the aging process, raises significant ethical concerns regarding societal attitudes, individual autonomy, and the overall well-being of older adults. A critical examination of these ethical dimensions is crucial for developing policies and practices that promote the dignity and respect of all individuals, regardless of age or level of engagement.

Societal Attitudes and Aging

Negative societal stereotypes surrounding aging and disengagement contribute to ageism, impacting healthcare resource allocation and employment practices. These biases often lead to unequal access to care and opportunities, disproportionately affecting older adults from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

| Policy/Practice | Country | Impact on Well-being (High/Medium/Low) | Socioeconomic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandatory retirement age (65) | United States | High (for those lacking savings/alternative income) | Disproportionately affects lower socioeconomic groups, leading to financial insecurity. |

| Limited access to specialized geriatric care in rural areas | Canada | Medium (access dependent on location and resources) | Impacts lower socioeconomic groups more significantly due to limited transportation and financial constraints. |

| Age-based discrimination in hiring practices | Japan | High (for older workers seeking re-employment) | Significant impact on lower socioeconomic groups relying on continued employment for income. |

The ethical conflict between societal expectations of productivity and the realities of physical and cognitive decline necessitates a nuanced approach. Pressuring individuals to remain active despite limitations clashes with the ethical principle of respecting individual autonomy and capabilities. Utilitarianism, focusing on maximizing overall well-being, might advocate for interventions promoting continued engagement. However, deontology, emphasizing inherent rights and duties, prioritizes respecting individual choices, even if they lead to less societal productivity.

Respecting Autonomy

Informed consent is paramount in healthcare decisions for older adults, particularly those with diminished cognitive capacity. Surrogate decision-making, while necessary in some cases, requires careful consideration to prevent coercion or undue influence.

The following flowchart illustrates a simplified decision-making process:

Start: Does the older adult have capacity to make decisions? → Yes: Informed consent obtained. → No: Identify surrogate decision-maker (family, legal guardian, etc.) → Determine the older adult’s best interests based on values and preferences (if known) → Make decision in accordance with best interests → End

Balancing autonomy with safety and well-being presents ethical challenges. For instance, respecting an older adult’s desire to live independently might conflict with concerns about their safety. Legal frameworks, such as guardianship laws, aim to resolve such conflicts, but careful consideration of individual circumstances is crucial.

Societal Impact on Well-being

Societal attitudes significantly influence the mental health of older adults. Negative perceptions can lead to increased rates of depression and social isolation.

A 2022 study published in the “Journal of Gerontology” found a strong correlation between negative societal stereotypes about aging and increased rates of depression among older adults in urban settings. The study highlighted the need for public health interventions aimed at challenging ageist attitudes and promoting positive perceptions of aging.

| Cultural Context | Attitude towards Aging | Access to Healthcare | Social Support | Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan (traditional) | Respect for elders, emphasis on family care | Generally good access, but potential challenges for those living alone | Strong family support networks, but declining in recent years | Generally high, but varies based on socioeconomic status and health |

| United States (modern) | Mixed attitudes, emphasis on youthfulness and independence | Access varies widely based on insurance and socioeconomic status | Social support networks can be fragmented, with less emphasis on family care | Highly variable, influenced by socioeconomic factors and health status |

Healthcare professionals, families, and society have an ethical obligation to ensure the dignity and respect of older adults. This requires fostering inclusive environments, providing accessible care, and promoting intergenerational understanding.

- Implement age-sensitivity training for healthcare professionals and caregivers.

- Promote intergenerational programs to foster positive interactions between different age groups.

- Advocate for policies that address age discrimination in employment and healthcare.

- Support community-based services that promote social engagement and well-being for older adults.

Future Directions in Research on Disengagement

Research on disengagement, while having made significant strides, still faces several key challenges. A more nuanced understanding requires innovative methodologies, interdisciplinary collaborations, and a rigorous ethical framework. Future research should focus on refining existing theories, exploring understudied populations, and developing effective interventions.

Identifying Specific Research Gaps

Addressing existing gaps in disengagement research is crucial for developing a comprehensive understanding of this multifaceted phenomenon. This involves creating more precise measurement tools, employing longitudinal study designs, and focusing on specific vulnerable populations.

Quantifiable Metrics for Disengagement

The development of robust, quantifiable metrics is essential for comparing disengagement across diverse contexts and populations. Current measures often lack precision and fail to capture the subtle nuances of disengagement. The table below presents some potential metrics, acknowledging their limitations.

| Metric | Context | Measurement Method | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Turnover Rate | Workplace | HR data, exit interviews | Doesn’t capture subtle forms of disengagement, such as reduced effort or decreased commitment. |

| Student Absenteeism Rate | Education | Attendance records | May not reflect lack of engagement in class, even with regular attendance. A student could be physically present but mentally disengaged. |

| Social Media Interaction Frequency | Social Groups | Frequency of posts/comments | Susceptible to manipulation, self-reporting bias, and doesn’t account for the quality of interaction. |

| Task Completion Rate | Project Teams | Project management software | Ignores quality of work, effort invested, and potential for collaborative task completion. |

Longitudinal Studies on Disengagement