What is practice theory in sociology? It’s not just about big, sweeping social structures, but also the everyday actions—the practices—that shape our lives and society. Think about how you greet someone, the way you use your phone, or even your choice of coffee. These seemingly small actions are actually powerful forces that create and maintain social order, inequality, and even spark revolutions.

Practice theory dives deep into these everyday actions, exploring how they’re shaped by larger social forces and, in turn, how they shape those forces. It’s a dynamic interplay between individual agency and broader social structures, a fascinating dance that helps us understand how society functions and changes.

This vibrant field examines how our daily routines, habits, and interactions—from the mundane to the extraordinary—weave together to form the fabric of social life. It bridges the gap between individual actions and broader social structures, exploring how we both shape and are shaped by the world around us. We’ll unpack key concepts like habitus (those ingrained dispositions that guide our actions), the intricate relationship between agency and structure, and how practices contribute to both social reproduction and transformative change.

Get ready to explore the hidden power of everyday life!

Introduction to Practice Theory in Sociology

Eh, jadi gini ya, ngomongin praktik teori di sosiologi tuh kayak lagi ngeliat acara dangdut di tipi, rame, banyak pemainnya, tapi tetep ada alurnya. Intinya, praktik teori ini ngeliatin gimana tindakan individu itu ngebentuk dan juga dibentuk sama struktur sosial. Ga cuma teori-teori abstrak doang, tapi juga liat aksi nyata di lapangan, asli kayak lagi ngeliat pedagang kaki lima berjuang dapetin rejeki.Practice theory in sociology emphasizes the interplay between individual agency and social structures.

It argues that social structures aren’t just fixed, immutable things that dictate people’s behavior, but are constantly being created, recreated, and changed through the everyday actions of individuals. Think of it like this: the rules of a game (social structure) are important, but the way each player interprets and plays the game (individual agency) also shapes the outcome.

It’s a dynamic relationship, not a one-way street. Makanya, ngikutin praktik teori ini tuh kayak lagi main gundu, kadang menang, kadang kalah, tapi seru!

Core Tenets of Practice Theory

Praktik teori punya beberapa prinsip dasar yang jadi pegangan. Bayangin aja kayak resep masakan, kalo salah satu bahannya kurang, rasanya jadi beda. Nah, ini beberapa “bahan” pentingnya: pertama, penekanan pada tindakan manusia sebagai proses yang aktif dan kreatif, bukan cuma respon pasif terhadap struktur. Kedua, pengakuan bahwa tindakan itu selalu tertanam dalam konteks sosial dan budaya tertentu.

Ketiga, pentingnya memahami bagaimana praktik-praktik sosial mereproduksi dan mengubah struktur sosial. Keempat, penekanan pada proses negosiasi dan interpretasi makna dalam interaksi sosial. Pokoknya, komplit banget deh kayak nasi uduk komplit!

Relationship Between Practice Theory and Structuration Theory

Nah, ini agak mirip kayak dua saudara kembar, mirip tapi beda. Structuration theory, yang dikembangkan sama Anthony Giddens, lebih fokus pada mekanisme reproduksi struktur sosial. Sedangkan praktik teori lebih menekankan pada bagaimana individu menginterpretasi dan memodifikasi struktur tersebut melalui tindakan mereka. Jadi, kalo structuration theory lebih kayak “blueprint”-nya, praktik teori lebih kayak proses pembangunannya.

Gak bisa dipisahkan, tapi punya fokus yang berbeda. Kayak nasi goreng sama mie goreng, sama-sama enak, tapi beda rasa.

Historical Overview of the Development of Practice Theory in Sociology

Awalnya, munculnya praktik teori ini kayak kembang desa yang tumbuh perlahan. Meskipun ide-ide yang mendasarinya sudah ada sejak lama, tapi perkembangannya yang signifikan baru terjadi di abad ke-20, terutama dipicu oleh kritik terhadap teori strukturalisme dan fungsionalisme. Para tokoh seperti Pierre Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens, dan Michel de Certeau memberikan kontribusi besar dalam mengembangkan dan mempopulerkan praktik teori.

Practice theory in sociology emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between social structures and individual agency. Understanding this dynamic interplay requires a structured approach to knowledge acquisition, much like mastering music theory, which necessitates dedicated study as outlined in this comprehensive guide: how to learn music theory. Similarly, a thorough grasp of practice theory necessitates rigorous engagement with sociological literature and empirical research to fully appreciate its complexities.

Mereka menawarkan perspektif yang lebih dinamis dan nuansa terhadap hubungan antara individu dan struktur sosial. Kayak lagu dangdut, awalnya mungkin sederhana, tapi lama-lama jadi lebih kompleks dan menarik.

Key Concepts in Practice Theory

Nah, kalo ngomongin praktik teori di sosiologi, jangan sampe mikirnya cuma teori-teori kaku kayak batu akik, ya! Ini lebih kayak resep masakan Betawi: ada bahan baku (struktur), ada yang ngolah (agen), dan hasilnya? Ya, praktik sosial yang unik dan beraneka ragam, bisa seenak urap, bisa seenak gabus pucung!

Praktik teori itu sendiri nggak cuma ngeliatin struktur sosial aja, kayak misalnya sistem ekonomi atau politik yang udah mapan. Dia juga liatin gimana individu itu aktif berpartisipasi dan membentuk struktur itu. Jadi, gak cuma pasif nrima keadaan, tapi juga aktif ngubah dan menciptakan keadaan baru. Bayangin aja, kita semua kan kayak lagi main LEGO raksasa, struktur sosialnya LEGO-nya, dan kita semua yang nyusun dan bongkar pasang sesuka hati (ya, tetep ada aturan mainnya sih, gak asal bongkar pasang).

The Concept of “Practice” in Practice Theory

Di praktik teori, “praktik” itu bukan sekedar kegiatan sehari-hari yang biasa aja, kayak makan nasi uduk pagi-pagi. Ini lebih dalam dari itu. Praktik itu melibatkan tiga hal penting: doing, saying, being. Jadi, gak cuma ngapain ( doing), tapi juga ngomong apa ( saying) dan jadi siapa ( being) saat melakukan hal tersebut.

Misalnya, jualan bakso di pinggir jalan. Itu bukan cuma ngegoreng bakso doang, tapi juga cara ngobrol sama pembeli, cara menata dagangan, bahkan cara berpakaian juga ikut membentuk “praktik” jualan bakso itu sendiri. Semua itu saling berkaitan dan membentuk makna yang lebih luas. Bayangin deh, kalo jualan bakso sambil pake jas, pasti aneh banget kan?

Itu contoh gimana doing, saying, being saling berkaitan.

Agency and Structure in Shaping Social Practices

Nah, ini dia inti dari praktik teori: pertarungan antara agen dan struktur. Agen itu individu atau kelompok yang punya kebebasan bertindak, sedangkan struktur itu aturan-aturan, norma, dan institusi yang membatasi kebebasan bertindak itu. Bayangin aja, mau ngebangun rumah di tanah orang, ya gak bisa dong! Itu struktur yang membatasi agen.

Tapi, agen juga bisa mempengaruhi struktur. Contohnya, gerakan #MeToo yang berhasil mengubah persepsi masyarakat terhadap pelecehan seksual. Jadi, hubungannya dinamis, saling mempengaruhi.

The Role of Habitus in the Reproduction and Transformation of Social Practices

Habitus itu kayak “program bawaan” yang ngaruhin cara kita berpikir, bertindak, dan merasakan. Ini dibentuk oleh pengalaman sosial kita sepanjang hidup, khususnya dari keluarga dan lingkungan sekitar. Habitus ini bisa mereproduksi praktik-praktik sosial yang sudah ada, tapi juga bisa menciptakan praktik-praktik baru.

Misalnya, anak orang kaya mungkin punya habitus yang berbeda dengan anak orang miskin, dan itu akan mempengaruhi cara mereka berinteraksi di masyarakat. Tapi inget, habitus bukan sesuatu yang kaku, dia bisa berubah seiring waktu dan pengalaman.

Practice Theory and Social Reproduction

Nah, ini mah kayak lagi ngobrol di warung kopi, santai aja. Practice theory, gimana ya, ngebayanginnya kayak gini: kita semua ini aktor, main peran di panggung kehidupan. Tapi skripnya ga baku, kita yang bikin improvisasi sendiri-sendiri, tapi tetep ada batasannya, ada aturan mainnya, ada ‘setting’ panggungnya. Nah, gimana setting panggung itu tetep ada, bahkan berubah, dan gimana peran kita ngaruh ke kestabilan dan perubahan itu?

Itulah yang dibahas di sini.Practice theory menjelaskan stabilitas dan perubahan dalam sistem sosial lewat cara pandang yang unik. Bukan cuma liat struktur sosial yang kaku, tapi juga aksi-aksi individu yang membentuk dan dibentuk oleh struktur itu. Bayangin kayak main domino, satu jatuh, yang lain ikutan jatuh. Tapi kita juga bisa ubah susunan dominonya, kan?

Nah, aksi-aksi individu itu menghasilkan reproduksi sosial (sistem sosial tetep jalan), tapi juga bisa bikin perubahan, kayak domino yang disusun ulang. Aksi-aksi kecil, ternyata punya efek besar, begitu juga sebaliknya. Jadi, stabilitas dan perubahan itu saling berkaitan, nggak bisa dipisahin.

Social Practices and the Reproduction of Social Inequalities

Gimana praktik sosial sehari-hari itu ngebantu pertahanin ketidaksetaraan sosial? Gampang, bayangin aja sistem pendidikan. Sekolah bagus, fasilitas lengkap, biasanya ada di daerah elit, anak-anak orang kaya yang bisa akses. Anak kampung? Susah.

Ini bukan cuma masalah uang, tapi juga akses informasi, lingkungan, dan kesempatan. Jadi, praktik sosial kayak sistem pendidikan ini secara nggak langsung menjaga status quo, si kaya tetep kaya, si miskin tetep susah. Contoh lainnya, akses kesehatan. Rumah sakit bagus, dokter handal, biasanya mahal.

Yang mampu? Ya, orang kaya. Yang miskin? Ya, ngantri panjang, atau bahkan gak bisa berobat sama sekali. Ini semua contoh bagaimana praktik sosial memperkuat ketidaksetaraan.

Social Practices and the Maintenance of Power Structures

Nah, ini yang seru. Gimana praktik sosial itu menjaga struktur kekuasaan? Contohnya, bahasa. Bahasa ga cuma alat komunikasi, tapi juga alat menunjukkan kekuasaan. Bayangin orang berkuasa pake bahasa tertentu, orang lain harus ikut pake bahasa itu biar diterima.

Yang nggak bisa? Ya, terpinggirkan. Contoh lain, sistem hukum. Hukum harusnya adil, tapi aplikasi hukumnya bisa dipengaruhi oleh kekuasaan. Orang kaya bisa upah pengacara mahal, orang miskin?

Ya susah bela diri. Ini menunjukkan bagaimana praktik sosial, walaupun terlihat netral, bisa jadi alat untuk mempertahankan struktur kekuasaan yang ada. Jadi, gak cuma tentang aturan tertulis, tapi juga praktik sehari-hari yang menciptakan dan mempertahankan kekuasaan.

Practice Theory and Social Change

Practice theory,

- asliii*, doesn’t just describe how society works; it shows how it changes, too. It’s not just about observing the

- rame-rame* (bustle) of daily life, but understanding how those everyday actions – the practices – build, challenge, and reshape the social world. We’ll explore how seemingly small acts can accumulate to create significant social shifts, both in resistance and transformation. Think of it like making

- wuih*, you’ve got something amazing (or maybe a bit

- nyleneh*, depending on your taste!).

gado-gado*

one ingredient might not seem like much, but combine them all, and

Social Practices as Sites of Resistance and Social Change

Social practices aren’t just passive; they’re active sites of both resistance and change. People don’t justikut arus* (go with the flow); they actively shape their world through their actions. This section will examine specific examples showcasing how collective action, rooted in shared practices, can challenge existing power structures and bring about societal transformation.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott as a Practice of Resistance

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956) serves as a powerful illustration. The practice of refusing to ride segregated buses, a seemingly simple act, became a potent tool of resistance against racial segregation in the United States. Black citizens, led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., collectively chose to walk, carpool, and utilize alternative transportation, significantly impacting the bus company’s revenue.

Estimates suggest that participation reached upwards of 90% of the Black community, crippling the bus system’s profitability and putting immense pressure on the city’s segregationist policies. This sustained collective practice, fueled by shared experiences of injustice, ultimately contributed to the landmark Supreme Court decision declaring bus segregation unconstitutional. The boycott’s economic impact, while difficult to precisely quantify, was undeniable, forcing the city to acknowledge the power of collective action.

Contemporary Climate Activism: A Digital and Physical Practice of Resistance

Contemporary climate activism offers a more recent example. The practice of organized protests, strikes (like the Fridays for Future movement), and divestment campaigns represent a concerted effort to resist environmental degradation and push for climate justice. These practices leverage both physical demonstrations and digital platforms like social media for mobilization and awareness-raising. A SWOT analysis of this movement would reveal strengths in its global reach and diverse participation, weaknesses in potential for fragmentation and co-optation, opportunities for policy influence and technological innovation, and threats from government repression and corporate lobbying.

The impact is multifaceted, from influencing public opinion and shifting corporate strategies to impacting policy discussions at national and international levels.

Comparative Analysis of Resistance Practices

Both the Montgomery Bus Boycott and contemporary climate activism demonstrate the power of collective action rooted in shared practices. While the former relied primarily on physical boycott and community organizing, the latter leverages digital technologies for wider mobilization. Both, however, demonstrate the capacity of collective action to challenge power structures and achieve measurable social change. The success of each, however, depends on various factors including the level of participation, the strategic deployment of tactics, and the broader political and social context.

The long-term consequences of both are significant, showcasing the lasting impact of collective action in shaping social norms and policy.

Collective Action Emerging from Shared Social Practices

This section analyzes how shared practices become the bedrock of collective action, examining both historical and contemporary examples. The underlying principle is that shared experiences and common practices create a sense of collective identity and facilitate coordinated action.

Labor Unions and Shared Workplace Practices

The formation of labor unions provides a compelling historical example. Shared experiences of exploitative working conditions and unfair labor practices within factories and mines fostered a collective identity among workers. This shared experience, coupled with common workplace practices, led to the organization of labor unions, which then used collective bargaining and strikes to negotiate better wages, working conditions, and benefits.

A timeline would show the evolution from initial localized actions to the formation of national and international unions, highlighting the gradual expansion of collective action fueled by shared workplace practices.

Online Activism and Shared Digital Practices

Contemporary online activism demonstrates the power of shared digital practices in mobilizing collective action. Social media platforms provide avenues for rapid information dissemination, organizing, and collective expression. Viral campaigns and online petitions leverage the shared practices of social media engagement to amplify voices and coordinate actions across geographical boundaries. For example, the #MeToo movement effectively used shared practices of online storytelling and hashtag activism to raise awareness about sexual harassment and assault.

The digital environment presents both opportunities (wide reach, rapid mobilization) and challenges (information manipulation, echo chambers, online harassment).

Comparison of Collective Action Mechanisms

| Social Practice | Mechanism of Collective Action | Scale | Outcome | Challenges ||————————–|———————————|——————–|———————————————|————————————————-|| Shared Workplace Practices | Unionization, Collective Bargaining | Local to Global | Improved wages, working conditions, benefits | Internal divisions, employer resistance || Shared Digital Practices | Online petitions, viral campaigns | Global | Increased awareness, policy influence | Information manipulation, online harassment, echo chambers |

Innovation and Adaptation in Transforming Social Practices

Innovation and adaptation are crucial aspects of social change, as they modify existing practices or create entirely new ones, leading to significant societal transformations.

The Printing Press: An Innovation Driving Social Change, What is practice theory in sociology

The invention of the printing press revolutionized information dissemination. This innovation significantly impacted social practices related to knowledge production, distribution, and consumption. The ability to mass-produce books democratized access to information, fueling literacy, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution. Its cascading effects touched upon social movements, religious practices, and scientific inquiry, fundamentally altering the course of history.

Adaptation of Religious Practices

The adaptation of religious practices to new cultural contexts demonstrates the dynamic nature of social practices. For example, the syncretism observed in many religious traditions shows how core beliefs and practices adapt to incorporate local customs and beliefs. This adaptation can result in the emergence of new religious expressions and the integration of religious practices into the broader social fabric of a community.

The process of adaptation can be influenced by various factors, including migration, colonialism, and interfaith dialogue. It highlights the flexibility and resilience of social practices in responding to changing circumstances.

“Social practices are not fixed entities; they are constantly being negotiated, contested, and transformed through processes of innovation and adaptation. This dynamic interplay between practice, innovation, and adaptation is central to understanding how social change occurs.” – (Hypothetical quote from a relevant sociological text – replace with a real quote and citation).

This quote emphasizes the fluidity of social practices and their role in shaping social change. The examples of the printing press and religious adaptation clearly demonstrate this continuous process of innovation and adaptation, leading to profound and lasting social transformations.

Methods for Studying Social Practices

Nah, ngomongin metode riset praktik sosial tuh kayak lagi ngeramein warung kopi, banyak banget pilihannya, masing-masing punya rasa dan aroma yang beda-beda. Penting banget nih milih metode yang pas, biar ga ‘keselek’ data, eh maksudnya biar hasil risetnya berkualitas dan ngena di hati pembaca. Pokoknya, jangan asal comberan, ya!Studying social practices requires careful consideration of methodology.

The choice of method significantly impacts the type of data collected and the conclusions drawn. Different approaches offer unique strengths and limitations.

Practice theory in sociology emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between social structures and individual agency. Understanding how individuals shape and are shaped by social norms requires examining the interplay of these forces, a concept mirrored in the informal theories of psychology; for instance, exploring what are examples of an informal theory in psychology can illuminate the cognitive processes underlying the adoption and negotiation of social practices.

Ultimately, both fields highlight the dynamic and iterative nature of social interaction.

Ethnography and Discourse Analysis: A Comparative Overview

Ethnography dan discourse analysis, dua metode yang sering dipake buat ngeliatin praktik sosial. Bayangin aja, ethnography kayak ‘nyamar’ jadi bagian dari komunitas yang lagi diteliti, ngamatin langsung aktivitas mereka, ngobrol rame-rame, sampai ngerasain suasana sehari-hari mereka. Sedangkan discourse analysis, lebih fokus ngeanalisa teks dan percakapan, ngeliatin gimana bahasa dipake buat ngebuat makna dan ngebentuk realitas sosial.

Keduanya punya kelebihan dan kekurangan masing-masing, tergantung tujuan riset dan jenis praktik sosial yang dipelajari. Jangan sampe salah pilih, ntar risetnya malah jadi bubur!

Research Project: Investigating the Practice of “Ngopi” in Betawi Culture

Misalnya, kita mau ngeliatin praktik ‘ngopi’ di budaya Betawi. Kita bisa pake practice theory buat ngeliat gimana praktik ngopi ini ngebentuk identitas sosial, ngebangun hubungan sosial, dan ngaruhin kehidupan sehari-hari masyarakat Betawi. Kita bisa pake metode etnografi, ngikutin aktivitas ngopi di warung-warung kopi tradisional, ngobrol sama para pelanggan dan pemilik warung, ngamatin ritual ngopi mereka, dan ngeanalisa makna yang terkandung di dalamnya.

Data yang dikumpulkan bisa berupa catatan lapangan, rekaman audio-visual, dan hasil wawancara. Analisa datanya bisa fokus pada gimana praktik ngopi ini ngebentuk relasi sosial, ngasih makna terhadap waktu dan ruang, dan ngebentuk identitas kelompok.

Ethnographic Study Design: The Practice of “Gotong Royong” in a Rural Village

Bayangin kita mau ngeliatin praktik ‘gotong royong’ di desa. Kita bisa desain penelitian etnografi dengan langkah-langkah berikut: Pertama, tentuin lokasi penelitian dan kelompok masyarakat yang akan diteliti. Kedua, bangun rapport dengan masyarakat setempat, agar mereka nyaman dan mau berbagi informasi.

Ketiga, kumpulin data dengan cara observasi partisipan, wawancara mendalam, dan dokumentasi foto atau video. Keempat, analisa data secara kualitatif, dengan fokus pada proses gotong royong, makna yang terkandung di dalamnya, dan perannya dalam kehidupan masyarakat.

Kelima, tulis laporan penelitian yang sistematis dan komprehensif. Jangan lupa siapkan perlengkapan riset yang memadai, seperti buku catatan, alat rekaman, dan kamera. Yang penting tetep jaga etika penelitian ya! Jangan sampai malah jadi ‘pencuri’ informasi.

Applications of Practice Theory

Practice theory,

- cuih*, it’s not just some abstract sociological mumbo-jumbo,

- ya tau!* It’s actually got some serious real-world applications, like understanding why your

- temen* keeps buying those overpriced

- sneakers*, or figuring out how to improve

- kebersihan* in your neighborhood. Let’s dive into some examples,

- deh*.

Practice Theory in Organizational Studies

Practice theory offers a powerful lens for analyzing organizational life, moving beyond simply looking at structures and formal rules. It helps us understand how everyday actions, routines, and interactions shape organizational culture and performance. Instead of focusing solely on formal organizational charts, practice theory investigates the informal practices that actually govern how work gets done. For example, researchers might analyze the unspoken rules governing communication within a team, how decisions are really made (not just on paper), or how power dynamics play out in daily interactions.

This approach reveals the often-hidden mechanisms that drive organizational behavior, leading to more nuanced and insightful understandings. Think of it like this: the official company manual says one thing, but the actual

- praktek* in the office is something completely different—and practice theory helps uncover that

- beda*.

Practice Theory and Consumer Behavior

Forget those fancy market research surveys! Practice theory offers a different approach to understanding consumer behavior. It focuses on the practices consumers engage in—not just their purchasing decisions, but the entire constellation of activities surrounding a product or service. For instance, instead of just asking why someone buys a particular brand of coffee, practice theory explores the rituals and routines associated with coffee consumption—from the preparation, to the social setting, to the perceived status associated with the chosen brand.

This holistic perspective reveals the social and cultural meanings embedded in consumption practices, providing a richer understanding of consumer motivations than traditional approaches. Understanding these practices allows marketers to craft more effective campaigns by connecting their products to existing consumer routines and social meanings. It’s about understanding the

- lifestyle*, not just the

- product*.

Practice Theory and Policy Interventions

Policy makers,

- eh*, they often make policies based on assumptions about how people behave, which aren’t always accurate. Practice theory can help bridge this gap. By understanding the practices that shape people’s behavior, policymakers can design more effective interventions. For example, a public health campaign aimed at improving diet might be more successful if it targets the specific practices surrounding food preparation and consumption within a community, rather than simply providing generic nutritional advice.

Similarly, policies aimed at promoting sustainable practices need to consider the ingrained routines and habits that need to be changed. It’s about understanding the

- everyday reality* of the people the policy is meant to affect, not just the abstract ideals. Instead of just

- ngomong*, practice theory helps design policies that actually

- work* in the real world.

Criticisms of Practice Theory

Practice theory, while offering valuable insights into the interplay between individual agency and social structures, isn’t without its critics. Like a Betawinasi uduk* that’s a bit too oily – delicious, but maybe needs a little tweaking – practice theory has aspects that some sociologists find problematic. This section will examine these criticisms, focusing on its handling of agency versus structure, power dynamics, and empirical testability.

We’ll then compare it to other sociological perspectives to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its strengths and weaknesses.

Agency versus Structure in Practice Theory

Practice theory attempts to navigate the enduring agency-structure debate by emphasizing the recursive relationship between the two. Practices are seen as both shaped by and shaping social structures. However, critics argue that this approach sometimes underplays the influence of either agency or structure. Some contend that the focus on practices risks neglecting the overarching power of structural constraints, while others believe it insufficiently acknowledges the creative capacity of individual actors to challenge and transform those structures.

For example, a critique might argue that while practice theory might explain how individuals within a patriarchal society reproduce gender norms through their daily interactions, it doesn’t fully capture the systemic nature of patriarchy itself, and how it actively limits choices and opportunities. Conversely, a different critique might suggest that the emphasis on the reproduction of structures through practices downplays the potential for transformative agency.

Power Dynamics in Practice Theory

Another area of contention revolves around practice theory’s treatment of power relations. While acknowledging that practices are often embedded within power structures, some critics argue that practice theory doesn’t adequately address the

asymmetrical* nature of power. It can sometimes appear to treat power as a diffuse and evenly distributed force, overlooking the ways in which power imbalances shape and constrain practices. Consider the case of workplace practices

a practice theory analysis might focus on the everyday interactions between managers and employees, but might fail to adequately analyze the inherent power imbalance shaped by managerial authority and access to resources. This neglects the systemic power dynamics which determine the possibilities for action available to different social groups.

Empirical Testability of Practice Theory

The abstract nature of “practice” itself presents a significant methodological challenge. Critics question how practices, often multifaceted and context-dependent, can be reliably observed and measured. The lack of standardized definitions and the inherent difficulty in separating individual agency from structural influences make empirical testing complex. Imagine trying to measure the “practice” of ngobrol* (casual chatting) – it’s fluid, culturally specific, and varies greatly depending on the context and participants.

How do you quantify that and link it to larger social structures in a way that is both rigorous and meaningful? The lack of clear operationalizations makes it difficult to generate testable hypotheses and to conduct rigorous empirical research.

Comparison with Other Sociological Perspectives

| Sociological Perspective | Comparison Points | Similarities | Differences | Examples of Scholars/Theories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structuration Theory (Giddens) | Emphasis on agency and structure, role of rules and resources | Shared focus on the dynamic interplay between agency and structure; both acknowledge the recursive relationship. | Practice theory places less emphasis on consciousness and intentionality compared to Giddens’ structuration theory. | Giddens, Archer |

| Actor-Network Theory (Latour) | Focus on networks and relations | Shared interest in how practices shape social worlds; both emphasize the relational nature of social phenomena. | ANT has a different ontological assumption about actors and networks; it treats non-human actors as equally important. | Latour, Callon |

| Bourdieu’s Habitus and Field | Concept of habitus and its role in shaping practices | Shared concern with the reproduction of social inequalities; both examine how practices contribute to social order. | Bourdieu’s theory places stronger emphasis on the role of habitus in shaping individual dispositions and actions, while practice theory focuses more on collective practices. | Bourdieu, Wacquant |

Practice Theory and Power Relations

Practice theory,

- asik banget* (really cool), offers a nuanced understanding of how power isn’t just a top-down force, but something woven into the fabric of everyday life. It’s not just about who’s got the biggest stick,

- tau gak?* (you know?), but about the subtle ways power shapes our actions and interactions within specific social practices. This section will examine how power operates within and through social practices, focusing on the specific example of online dating.

Power Dynamics in Online Dating

Online dating,wah* (wow), a seemingly casual social practice, is rife with power dynamics. It’s a space where individuals navigate complex power relations related to desirability, attractiveness, and access to potential partners. These power dynamics are shaped by factors like age, race, gender, socioeconomic status, physical appearance, and even technological literacy. The platform itself also plays a significant role, with algorithms and design features influencing who users see and interact with.

Mechanisms of Power in Online Dating

Several mechanisms of power are at play. Control of resources, for example, manifests in the form of premium subscriptions offering enhanced visibility and features. Users with these subscriptions effectively have more power to shape their online dating experience. Symbolic violence is evident in the constant pressure to conform to idealized images of beauty and desirability, often reinforced through the platform’s design and user comments.

Discursive strategies, like crafting the perfect profile and using specific language to convey a desired image, are crucial in shaping perceptions and attracting potential partners. Surveillance, in the form of profile stalking and scrutinizing photos, is another mechanism. Finally, the inherent power imbalance between users with more attractive profiles and those with less can be seen as a form of subtle coercion.

Levels of Power in Online Dating

Power dynamics operate at multiple levels. At the individual level, users with desirable profiles hold more power to attract potential partners. At the group level, certain demographic groups might experience systematic disadvantages, reflecting broader societal inequalities. For example, women might face a higher volume of unwanted or aggressive messages compared to men. At the institutional level, the dating app companies themselves wield significant power through their algorithms, terms of service, and data collection practices.

These levels interact, with institutional structures shaping individual and group-level power dynamics. For instance, algorithms that prioritize certain profile types based on attractiveness reinforce existing inequalities.

Exerting Power in Online Dating

Individuals exert power through various strategies. Creating a visually appealing profile, strategically choosing photos and descriptions, and engaging in skillful communication are all ways of maximizing one’s attractiveness and gaining more control over the dating process. Using premium features and strategically employing messaging tactics to elicit desired responses are further examples of exerting power. The effective use of these strategies can lead to more dates, more options, and ultimately, more power within the online dating context.

Resisting Power in Online Dating

Resistance to power manifests in various ways. Individuals might actively challenge unrealistic beauty standards by presenting themselves authentically, rejecting pressure to conform to specific gender roles, or creating profiles that explicitly reject typical online dating tropes. Collective action, such as forming online communities that discuss and critique the power dynamics within online dating, is another form of resistance. Furthermore, users might choose to use alternative dating methods altogether, demonstrating a rejection of the dominant power structures of the platform.

Power Shifts in Online Dating

Power dynamics in online dating are not static. Technological advancements, changing social norms, and evolving user behaviors all contribute to shifts in power. For example, the rise of awareness about online harassment has led to increased platform accountability and the implementation of safety features. Similarly, the growing popularity of alternative dating apps focused on inclusivity and social justice can be seen as a shift in power towards marginalized groups.

Social Institutions Shaping Online Dating

Several social institutions shape online dating. Technological companies design and control the platforms, influencing the user experience and power dynamics. Media representations of relationships and dating ideals shape user expectations and behaviors. Cultural norms around gender, sexuality, and relationships also play a crucial role in shaping the context and power dynamics of online dating. Laws concerning data privacy and online harassment provide a regulatory framework that can both enable and constrain power dynamics.

Mechanisms of Institutional Influence

These institutions exert their influence through various mechanisms. Laws and regulations set boundaries on data collection and user behavior. Media representations shape the norms and expectations around online dating, reinforcing certain ideals and practices. Technological companies exert power through algorithm design, data collection practices, and control over platform features. Cultural norms and values influence user behaviors and expectations, reinforcing existing power structures.

Consequences of Institutional Influence

Institutional influence has significant consequences for power dynamics. For example, algorithms that prioritize certain profile types can reinforce existing inequalities. Laws protecting user privacy can limit the ability of companies to exploit user data for profit. Media representations can perpetuate unrealistic beauty standards and reinforce gender stereotypes. Therefore, institutions both enable and limit the exertion and resistance of power within the online dating context.

Data Representation

| Aspect of Power | Exertion Examples | Resistance Examples | Institutional Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Resources | Premium subscriptions, advanced search filters | Using free features effectively, avoiding paid features | Platform’s pricing model, algorithm prioritizing paid users |

| Symbolic Violence | Pressure to conform to beauty standards, idealization of certain personality traits | Rejecting unrealistic beauty standards, presenting authentic self | Algorithmic promotion of certain “ideal” profiles, media portrayals of relationships |

| Discourse Control | Crafting a compelling profile, using specific language to attract desired partners | Creating profiles that challenge conventional norms, engaging in open and honest communication | Platform’s design features that limit profile length and expression |

| Surveillance | Stalking profiles, analyzing photos and messages | Protecting personal information, limiting profile visibility | Platform’s data collection practices, lack of robust privacy features |

Practice Theory and Identity Formation

Practice theory offers a compelling framework for understanding how individual and collective identities are formed and negotiated. It moves beyond simplistic notions of identity as fixed and inherent, instead emphasizing the dynamic interplay between individual agency and social structures, as mediated through everyday practices. This approach highlights the continuous process of identity construction and the crucial role of social practices in shaping our sense of self and belonging.

We’ll explore how participation in various social practices shapes self-perception, how collective identities are formed and maintained, and how context influences this dynamic relationship. The Betawi spirit of “santai” (relaxed) will be applied, but don’t worry, this isn’t about

- ngemper* (loafing around) – we’ll get to the

- inti* (core) of it all!

The Interplay of Social Practices and Identity Formation: Individual Identity

Participation in specific social practices significantly shapes individual self-perception and self-expression. Think of it like this: your identity is anasi uduk* (coconut rice), and the practices are the ingredients that give it its unique flavor. Each practice adds a distinct layer, influencing how you see yourself and how you present yourself to the world.

- Religious Observance: Regular participation in religious rituals, such as attending weekly mass or engaging in daily prayer, can foster a strong sense of belonging and shared identity within a religious community. This can lead to the internalization of religious values and beliefs, shaping moral compass and self-perception as a devout follower. For example, a devout Muslim who regularly attends Friday prayers might identify strongly with their Muslim identity and incorporate its values into their daily life.

- Participation in Sports: Involvement in competitive sports often cultivates a sense of teamwork, discipline, and achievement. The shared experience of training, competing, and celebrating victories fosters a sense of camaraderie and shared identity among team members. Imagine a member of a successful football team; their identity might be significantly shaped by their role within the team, leading to feelings of pride, belonging, and a sense of collective accomplishment.

- Online Gaming Communities: Active participation in online gaming communities can create a strong sense of belonging and shared identity based on shared interests and goals. Players often develop close relationships with fellow gamers, creating a sense of virtual community and shared identity. A player deeply involved in a specific online game might derive a significant part of their identity from their in-game achievements, interactions, and their place within the online community.

Habitus, as conceptualized by Pierre Bourdieu, plays a crucial role in the reproduction and transformation of individual identities through social practices. Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, dispositions, and tastes that shape our actions and perceptions. It’s like the

- bumbu rahasia* (secret spice) in your

- nasi uduk* – it’s what makes it uniquely

- you*. For instance, someone raised in a wealthy family might develop a habitus that favors certain cultural practices and lifestyles, influencing their identity and social standing. However, individuals can also actively challenge and transform their habitus through engagement in new social practices, leading to changes in their self-perception.

Individuals often navigate conflicting or competing social practices, leading to complex identity negotiations. Consider a young woman raised in a conservative religious family who also pursues a career in a secular and progressive environment. She might experience tension between the values and expectations of her family and the demands of her professional life, leading her to negotiate her identity in a way that balances these competing influences.

This might involve finding ways to express her religious beliefs while also participating fully in her professional life, creating a complex and nuanced identity.

The Interplay of Social Practices and Identity Formation: Collective Identity

Shared social practices are fundamental to the formation and maintenance of group identities. These practices create a sense of shared experience, values, and belonging, fostering a collective identity that transcends individual differences.

- National Identity: Shared national symbols, rituals, and narratives contribute to the formation of national identity. For example, celebrating national holidays, singing the national anthem, and participating in national commemorations reinforce a sense of shared belonging and national pride. These practices help to construct a collective narrative about the nation’s history, values, and future, creating a shared identity among citizens.

- Professional Identity: Shared professional practices, codes of conduct, and specialized knowledge contribute to the formation of professional identities. Doctors, lawyers, and engineers, for example, share common training, ethical standards, and professional networks that shape their collective identity. Their professional identity is often reflected in their dress code, language use, and interaction with colleagues and clients.

Symbolic boundaries, which are the markers used to distinguish groups, play a crucial role in defining and maintaining collective identities. These boundaries can be linguistic, material, or behavioral. For example, specific clothing styles, jargon, or rituals can be used to distinguish members of a particular subculture from others. Think of the distinct clothing styles and musical preferences associated with various youth subcultures, which serve as symbolic markers that reinforce group identity and distinguish them from the mainstream culture.Social practices can also be used to challenge and subvert existing collective identities.

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States, for example, used social practices like marches, boycotts, and sit-ins to challenge racial segregation and fight for equal rights. These practices were crucial in challenging the existing racial hierarchy and constructing a new collective identity based on racial equality.

The Dynamic Relationship Between Practice and Identity Negotiation

Identity is not a fixed entity but an ongoing process shaped by continuous engagement in social practices. It’s constantly being negotiated and renegotiated as individuals interact with their social environments. It’s a bit like a

kerak telor* (Jakarta’s traditional omelette)

it’s always evolving, adding new layers of flavor with every interaction.The interplay between individual agency and social structures is central to identity negotiation. Individuals are not passive recipients of social structures; they actively shape and reshape their identities through their choices and actions. However, these choices are always constrained by the social structures and norms within which they operate.

Individuals might reproduce existing social expectations through their practices, but they can also actively resist them and create new possibilities.Contextual factors, such as time period, geographical location, and social class, significantly influence the relationship between practice and identity negotiation. For example, the meaning and significance of certain social practices can vary across different cultures and historical periods. A practice that might be considered acceptable in one context might be deemed inappropriate or even taboo in another.

Specific Examples of Social Practices Shaping Self

| Social Practice | Impact on Sense of Self | Specific Example | Analysis of Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Observance | Development of strong moral compass, sense of community and belonging, shaped worldview. | A devout Catholic attending daily mass and actively participating in parish activities. | The individual’s identity is deeply rooted in their faith, influencing their moral values, social interactions, and overall worldview. Their sense of self is intertwined with their religious community and practices. |

| Participation in Sports | Development of teamwork, discipline, competitiveness, sense of accomplishment, physical fitness. | A dedicated marathon runner who trains rigorously and participates in various races. | The individual’s identity is strongly linked to their athletic pursuits, shaping their self-perception as disciplined, determined, and physically fit. Their sense of self-worth is often tied to their achievements in the sport. |

| Online Gaming Communities | Development of social skills, sense of belonging, shared identity with other players, potentially addiction. | A gamer who is actively involved in a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), regularly interacting with other players. | The individual’s identity is partly defined by their online persona and their relationships within the gaming community. Their sense of self is shaped by their in-game achievements, social interactions, and their place within the virtual world. |

| Political Activism | Development of strong political beliefs, sense of civic duty, sense of agency, potential for social change. | An individual who actively participates in protests, campaigns, and political organizing. | The individual’s identity is strongly tied to their political beliefs and actions. Their sense of self is shaped by their commitment to social justice and their role in advocating for change. |

Practice Theory and Technology: What Is Practice Theory In Sociology

Practice theory,asliii*, provides a powerful lens through which to examine the complex interplay between technology and society. It moves beyond simplistic notions of technological determinism, acknowledging that technology doesn’t just

happen* to us; it’s actively shaped and reshaped by our social practices, and vice-versa. Think of it like this

technology is the

- kendaraan*, but the

- tujuan perjalanan* and how we get there are defined by our social interactions and cultural contexts. This means understanding technology’s impact requires looking at how it’s integrated into everyday life, influencing and being influenced by existing social structures and power dynamics. It’s not just about the gadgets themselves,

- eh*, but about how we use them, what meaning we give them, and the consequences that follow.

Analyzing the Impact of Technology on Social Practices

This section examines how specific technologies have altered various social practices. The impact, both positive and negative, is explored through concrete examples.

| Technology | Social Practice | Impact (Positive and Negative) | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smartphones | Dating | Positive: Increased accessibility to potential partners, facilitated communication. Negative: Superficial interactions, pressure to maintain online persona, potential for catfishing. | Examples: Tinder, Bumble’s success; studies on online dating satisfaction rates; news reports on online dating scams. |

| Social Media Platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook) | Political Mobilization | Positive: Rapid dissemination of information, facilitated collective action, increased political awareness. Negative: Spread of misinformation, echo chambers, polarization, online harassment. | Examples: Arab Spring uprisings; #MeToo movement; research on political polarization on social media. |

| AI-powered Recommendation Systems | News Consumption | Positive: Personalized news feeds, potential for exposure to diverse perspectives (depending on algorithm design). Negative: Filter bubbles, echo chambers, limited exposure to opposing viewpoints, potential for manipulation. | Examples: Netflix recommendations; Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm; studies on filter bubbles and algorithmic bias. |

Case Study: The Impact of Smartphones on Social Interactions among Young Adults in Urban Jakarta

Smartphones have profoundly altered social interactions among young adults in urban Jakarta. The constant connectivity facilitates instant communication and strengthens existing relationships. However, it also leads to a decline in face-to-face interactions, impacting the development of essential social skills. The ubiquitous nature of smartphones in this context means that even during in-person gatherings, attention is often divided, leading to a sense of disconnect.

Socioeconomic factors play a role; those with better access to data and higher-end devices experience more benefits but also face greater pressure to maintain an active online presence. Geographic location also influences usage patterns; access to reliable internet in densely populated areas versus more remote suburbs varies significantly.

Comparative Analysis: Smartphones vs. Traditional Media in News Consumption

Smartphones and traditional media (newspapers, television) both serve as channels for news consumption, but their impacts differ significantly. Smartphones offer immediate updates and personalized news feeds, fostering a sense of immediacy but also contributing to information overload and the spread of misinformation. Traditional media, while slower, often provide more in-depth analysis and fact-checking, leading to potentially more informed citizenry but potentially limited reach and less diverse perspectives.

The differences stem from the technological capabilities of each medium and the ways in which they are integrated into social practices.

Technological Determinism vs. Social Construction of Technology

The debate between technological determinism and the social construction of technology highlights the complexities of technology’s impact. Technological determinism posits that technology dictates social change; for instance, the internet

- automatically* leads to globalization. Social constructionism, conversely, emphasizes that technology’s influence is mediated by social factors; the internet’s impact is shaped by how different societies adopt and adapt it. Both perspectives offer valuable insights, and a nuanced understanding requires acknowledging the reciprocal relationship between technology and society – a constant back-and-forth,

- gitu*.

Feedback Loops Between Technology and Social Practices

The introduction of ride-hailing apps like Gojek and Grab illustrates feedback loops. Initially, these apps improved transportation accessibility. This led to changes in commuting habits, influencing urban planning and traffic patterns. These changes, in turn, fueled further app development, leading to features like real-time traffic updates and route optimization. This continuous interaction between technology and social practices shapes the evolution of both.

Unintended Consequences of Social Media on Social Movements

Social media’s use in social movements, while beneficial in disseminating information and mobilizing supporters, has also led to unintended consequences. The ease of organizing online can also lead to fragmented movements lacking cohesive leadership or clear goals. Furthermore, the reliance on online platforms for mobilization makes movements vulnerable to government censorship or manipulation.

The Role of Digital Technologies in the Reproduction and Transformation of Social Practices

Digital technologies can both reproduce and transform social practices. For instance, online platforms often reflect and amplify existing inequalities, as seen in algorithmic bias that disproportionately affects certain groups. However, they also enable new forms of social interaction and activism, creating spaces for marginalized voices and challenging established power structures.

Reproduction of Existing Practices: Online Harassment

Online harassment replicates existing gender inequalities by targeting women disproportionately. The anonymity and scale afforded by digital platforms amplify the harassment, creating a hostile online environment that silences women’s voices and restricts their participation in online spaces.

Transformation of Practices: E-commerce and Education

E-commerce has fundamentally transformed retail, offering unprecedented convenience and accessibility. Online education has expanded access to learning opportunities, particularly for those in remote areas or with limited mobility. These transformations have changed the speed, scale, and accessibility of these practices, impacting economic activities and educational opportunities globally.

Resistance and Adaptation to Digital Technologies

While many embrace digital technologies, resistance and adaptation also occur. Some individuals and communities actively limit their use of technology, seeking to preserve traditional practices or protect their privacy. Others adapt by developing strategies to navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by digital technologies, finding ways to use them to their advantage while mitigating potential harms.

Illustrative Examples of Social Practices

Nah, kita bahas contoh-contoh praktik sosial yang ada di sekitar kita, biar gak cuma teori doang. Gimana ya, kaya ngeliat ‘geng motor’ tapi versi akademis gitu deh. Asik kan?

Memahami praktik sosial itu penting, soalnya ini yang membentuk kehidupan kita sehari-hari. Dari hal sepele sampe yang gede, semua terbentuk dari interaksi dan kebiasaan yang terulang. Bayangin aja, kalau gak ada praktik sosial, kita bakalan hidup kayak zombie, jalan aja bingung!

Examples of Social Practices

Berikut ini beberapa contoh praktik sosial, lengkap dengan aktor, sumber daya material, dan simbolisnya. Bayangin aja kayak lagi bikin daftar belanja, tapi belanjaannya kebiasaan orang!

| Social Practice | Key Actors | Material Resources | Symbolic Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning Coffee Ritual | Individuals, Baristas, Coffee Shop Owners | Coffee beans, coffee machine, mugs, sugar, milk, money | Sense of community, social interaction, relaxation, status symbol (e.g., specialty coffee) |

| Going to the Gym | Individuals, Fitness Instructors, Gym Owners | Gym equipment, weights, workout clothes, gym membership card, gym facilities | Health, fitness, self-improvement, social status (e.g., body image), sense of accomplishment |

| Participating in a Religious Service | Congregants, Religious Leaders, Church Staff | Church building, religious texts, musical instruments, candles, offerings | Faith, community, spiritual guidance, moral values, social support |

| Using Social Media | Individuals, Social Media Companies, Influencers | Smartphones, computers, internet access, social media apps | Social connection, information sharing, self-expression, social status (e.g., number of followers), entertainment |

| Attending a Football Match | Football players, fans, referees, stadium staff | Stadium, footballs, jerseys, tickets, concessions, security personnel | Team spirit, community, entertainment, rivalry, social identity (e.g., team affiliation) |

Practice Theory and the Body

Practice theory,

asliii*, provides a compelling lens through which to understand the intricate relationship between the body and social life. It moves beyond simply seeing the body as a passive recipient of social forces, recognizing instead its active role in shaping and being shaped by social practices. Think of it like this

your body isn’t just a vessel; it’s a key player in the ongoing social drama,

tau tau!*

The Body’s Involvement in and Shaping by Social Practices

The body is not a neutral entity; it’s deeply intertwined with the social practices we engage in. These practices actively shape our bodies, from the way we move and hold ourselves to the skills we acquire. Conversely, our bodies, with their capabilities and limitations, influence how we participate in these practices. This is a two-way street,

ngerti kan?*

Specific Social Practices and Bodily Involvement

- Religious Ritual: Consider a Muslim performing Salat (prayer). The body is actively shaped through specific postures (prostration, standing), movements (bowing, reciting), and the acquisition of skills (memorizing verses, understanding ritual procedures). Passively, the body is shaped by dress codes (covering the body according to religious norms) and the physical environment of the mosque (e.g., kneeling on a prayer mat). A pilgrimage to Mecca,

-masyaAllah*, involves extensive physical endurance, shaping the body through sustained walking, exposure to diverse climates, and potential physical challenges. - Professional Work: A surgeon’s body is actively shaped by years of training that develop fine motor skills, precision, and stamina. Their posture and movements are honed to perform complex procedures. Passively, the body is shaped by sterile environments, surgical gowns, and the constant use of specialized tools. A teacher’s body, on the other hand, might be shaped actively through gestures used to explain concepts and maintaining a dynamic posture while lecturing.

Passively, they might experience repetitive strain injuries from prolonged writing or standing.

- Leisure Activity: A competitive athlete’s body undergoes intense physical conditioning, developing strength, agility, and endurance. Their movements become highly refined and specialized. Passively, the body is shaped by equipment (e.g., sports gear), playing surfaces, and the rules of the game. A video gamer’s body might experience prolonged periods of sitting, leading to potential postural problems and repetitive strain injuries. Actively, however, their hand-eye coordination and reflexes are honed through intense gameplay.

Power Dynamics and Bodily Practices

Power dynamics significantly influence how bodies are involved in and shaped by social practices.

- Gender: Women in many cultures are expected to adopt specific postures and movements considered more “feminine,” limiting their physical freedom and expression. Conversely, men might be encouraged to engage in activities that develop physical strength and aggression.

- Class: Access to resources and opportunities influences how bodies are shaped. Individuals from wealthier backgrounds might have access to better healthcare, nutrition, and leisure activities, leading to different bodily experiences than those from less privileged backgrounds.

- Race: Racial stereotypes can influence how bodies are perceived and treated. Certain physical attributes might be associated with particular racial groups, shaping perceptions of athletic ability, intelligence, or even criminality.

- Ability: Social practices often exclude or marginalize individuals with disabilities. Adaptations and accommodations are often necessary to ensure participation, highlighting how social structures shape bodily experiences based on ability.

Technology’s Role in Mediating Bodily Practices

Technology plays a crucial role in mediating the body’s involvement in social practices. Think of smartphones,eh?* They shape our posture, our attention spans, and our interactions with others. Surgical tools extend the surgeon’s capabilities, while prosthetic limbs redefine bodily limits. Technology both enables and constrains bodily experiences.

Embodiment of Social Practices

Social practices aren’t just external actions; they’re deeply embodied. They become ingrained in our bodies, shaping our habits, movements, and emotional responses.

Habitus and Bodily Comportment

Bourdieu’s concept of habitus explains how social practices are embodied. Habitus refers to the deeply ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions that shape our actions and perceptions. It manifests in our bodily comportment, movement, and expression, reflecting our social class, background, and experiences. For example, the posture and gait of a wealthy individual might differ significantly from that of someone from a working-class background, reflecting their different life experiences and social positions.

Gimana, ngerti?*

Emotional Embodiment and Bodily Practices

Emotions are not just internal feelings; they are expressed and regulated through bodily practices. Social practices shape how we express and manage emotions. For instance, public displays of affection might be acceptable in some cultures but taboo in others, shaping how individuals regulate their emotional expressions through bodily actions.

The Body as a Site of Social Meaning

The body itself becomes a site for the inscription and expression of social meaning. Bodily modifications like tattoos, piercings, and even clothing choices convey social identities and affiliations. Posture, gait, and even facial expressions communicate social status, emotions, and intentions.

Wah, keren!*

Bodily Practices and Social Reproduction and Change

Bodily practices are not simply reflections of social structures; they actively contribute to their reproduction and transformation.

Bodily Practices and Social Reproduction

Bodily practices can reinforce social inequalities. Gendered divisions of labor, for example, often involve different bodily demands and expectations for men and women, perpetuating existing power dynamics. Class differences in access to healthcare and nutrition further contribute to disparities in physical health and well-being.

Bodily Practices and Social Change

However, bodily practices can also be sites of resistance and social change. Protests and activism often involve specific bodily actions—marches, sit-ins, and other forms of physical resistance—that challenge social norms and inequalities. The body becomes a tool for expressing dissent and demanding social justice.

Longitudinal Analysis of Bodily Practices

Bodily practices change over time, reflecting broader social transformations. Generational shifts in body image, fashion, and physical activity patterns reflect changing social norms and values. Consider the changing attitudes towards body weight and fitness over the past few decades.

Comparing Bodily Practices Across Social Contexts

| Social Practice | Body Shaping (Active) | Body Shaping (Passive | Power Dynamics Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious Ritual | Specific postures and movements during prayer, development of ritual skills | Dress codes, physical environment of the religious space | Gendered expectations in religious participation, class differences in access to pilgrimage |

| Professional Work | Development of fine motor skills, specialized movements, physical stamina | Use of protective gear, ergonomic design of workspace | Gendered occupational segregation, class differences in access to training and resources, racial bias in hiring |

| Leisure Activity | Development of athletic skills, physical conditioning, refinement of movements | Use of sports equipment, playing environment | Gendered participation in sports, class differences in access to leisure activities, racial stereotypes in athletic ability |

Practice Theory and Space

Practice theory,asliii*, offers a compelling framework for understanding the intricate dance between social practices and the spaces where they unfold. It’s not just about

ngegoler* in a particular location; it’s about how that location actively shapes the practice, and how the practice, in turn, reshapes the space. Think of it like this

the

- warteg* wouldn’t be the same without the

- rame-rame* of its regulars, and those regulars wouldn’t be the same without the

- warteg*’s comforting familiarity. This dynamic interplay is what we’ll explore, focusing on how space enables, constrains, and shapes social practices.

The Interplay of Social Practices and Spatial Elements

This section examines the relationship between three distinct social practices – religious ritual, political protest, and casual social interaction – and the spatial elements that define them. The spatial characteristics of each setting significantly influence the performance and outcome of the social practice itself.

Religious Ritual (Church Service)

A church service,kayaknya*, is deeply intertwined with its spatial context. The altar, a focal point symbolizing religious authority, dictates the flow of the service. Pews, arranged in rows, reinforce a hierarchical structure and guide participant behavior. Acoustics, impacting the audibility of prayers and sermons, influence the emotional and spiritual experience. Spatial constraints, such as limited seating or designated areas for different groups (choir, clergy), can regulate participation and interaction.

The architecture itself, perhaps grand and imposing or simple and intimate, reinforces the religious authority and the overall atmosphere of reverence or community.

Political Protest (Demonstration)

Political protests,wah* quite different, are heavily influenced by the spatial layout of the area. Street layouts, determining the routes of marches and the size of gatherings, can facilitate or hinder the movement of protesters. A central stage allows for speeches and rallies, organizing the crowd and focusing attention. The presence of sound systems amplifies voices and messages, reaching a wider audience.

Spatial constraints are significant; permits are often required, police presence can limit the protest’s scope, and crowd control measures can shape participant behavior and movement. The spatial organization directly impacts the protest’s visibility, reach, and overall effectiveness.

Casual Social Interaction (Coffee Shop)

Casual social interactions in a coffee shop,ah, santai*, are shaped by the spatial arrangement. Seating arrangements, whether intimate booths or communal tables, influence the type and intensity of interactions. Noise levels, affected by the coffee shop’s design and the number of patrons, affect conversation flow and comfort levels. The availability of Wi-Fi, often a key feature, shapes the types of interactions that occur, encouraging individual work or collaborative projects.

Spatial constraints include limited seating, noise levels that make conversation difficult, and time constraints imposed by the coffee shop’s closing time. The ambiance – from the lighting to the music – significantly shapes the overall mood and the kinds of interactions that feel natural and appropriate within the space.

Spatial Organization of Social Life: A Comparative Analysis

This section analyzes how pre-existing spatial arrangements influence social practices and vice versa, using a comparative analysis of a gentrified neighborhood and a low-income housing project.

Gentrified Neighborhood vs. Low-Income Housing Project

A gentrified neighborhood, typically characterized by renovated buildings, upscale amenities, and higher property values, often fosters social practices that reflect its economic and social standing. These spaces often attract residents who engage in practices associated with higher levels of disposable income and leisure time, such as frequenting cafes, attending art galleries, or participating in organized community events. The architecture, infrastructure, and access to resources all contribute to shaping the social interactions that occur.In contrast, a low-income housing project, often characterized by limited resources, aging infrastructure, and higher population density, tends to support different social practices.

Residents may engage in practices focused on survival, community support, and informal economic activities. The limited space and resources might lead to a greater emphasis on close-knit community networks and informal support systems. The spatial constraints imposed by the housing project’s design and limited resources directly influence the types of social practices that can thrive within its confines.

Over time, the ongoing social practices within these spaces can transform their physical and social organization, either reinforcing existing inequalities or creating opportunities for change.

Social Practices Creating and Transforming Social Spaces: Place-Making

This section explores how social practices actively shape and transform physical spaces through the concept of place-making.

Example 1: Graffiti Art

Graffiti art, often viewed as vandalism, can transform neglected urban spaces into vibrant canvases expressing social and political messages. The practice of creating graffiti alters the visual character of a wall or building, transforming it from a blank, often forgotten space into a site of artistic expression and community engagement. This transformation can lead to subsequent social interactions, such as organized graffiti tours or discussions about the art’s meaning and impact.

Technology, through photography and social media, further amplifies the reach and impact of these transformations.

Example 2: Community Gardens

Community gardens, established through collective effort, transform vacant lots or underutilized spaces into productive and aesthetically pleasing environments. The practice of cultivating a garden not only yields food but also fosters social interaction and community building. The transformation of a neglected space into a vibrant garden creates a shared space for residents to connect, learn, and cooperate, changing its social meaning and subsequent interactions.

Example 3: Street Festivals

Street festivals temporarily transform ordinary streets into lively public spaces filled with music, food, and social activity. The practice of organizing and participating in a street festival dramatically alters the character of a street, turning it into a space for celebration, community building, and cultural exchange. Technology, through social media promotion and live streaming, extends the reach and impact of these temporary transformations, creating lasting memories and impacting future interactions.

Future Directions in Practice Theory

Nah, ngomongin masa depan teori praktik tuh kayak lagi ngeliat pedagang kaki lima, rame, penuh kejutan, dan kadang-kadang bikin puyeng juga. Tapi, justru di situ serunya! Teori praktik sendiri kan masih berkembang, kayak anak muda yang lagi cari jati diri. Banyak banget potensi yang belum dieksplorasi, jadi kita bisa liat kemana arahnya nanti.Teori praktik punya potensi besar untuk ngebantu kita ngerti dan ngatasi masalah-masalah sosial zaman now.

Bayangin aja, kita bisa pake teori ini untuk ngeliat gimana kebiasaan sehari-hari orang mempengaruhi ketimpangan sosial, perubahan iklim, atau bahkan perkembangan teknologi. Ini bukan cuma teori di atas kertas aja, tapi bisa jadi alat praktis buat bikin perubahan nyata. Gak cuma wacana doang, ye kan?

Emerging Trends in Practice Theory

Beberapa tren yang lagi naik daun di teori praktik termasuk pengembangan metode analisis yang lebih canggih, fokus yang lebih besar pada aspek emosional dan tubuh dalam praktik sosial, dan integrasi teori praktik dengan pendekatan lain seperti teori aktor-jaringan dan analisis diskursus. Bayangin kayak lagi masak, dulu cuma pake pisau dan kompor, sekarang udah ada food processor dan oven canggih.

Makin banyak alat, makin kompleks, tapi hasilnya juga bisa makin mantap.

Applications of Practice Theory in Addressing Contemporary Social Issues

Teori praktik bisa banget diaplikasikan untuk ngatasi berbagai masalah sosial kontemporer. Misalnya, untuk ngerti gimana kebiasaan konsumsi kita mempengaruhi perubahan iklim, atau gimana praktik-praktik di media sosial membentuk persepsi kita tentang politik. Bahkan, teori ini bisa dipakai untuk desain intervensi kebijakan yang lebih efektif, karena fokusnya bukan cuma pada struktur sosial, tapi juga pada aksi individu dan interaksinya.

Kayak lagi bikin strategi pemasaran, harus tau target pasarnya dulu, gimana kebiasaan belanjanya, baru bisa bikin strategi yang pas.

Promising Avenues for Future Research in Practice Theory

Penelitian di bidang teori praktik masih banyak yang perlu digali. Misalnya, penelitian yang lebih mendalam tentang peran teknologi dalam membentuk praktik sosial, atau studi komparatif tentang praktik sosial di berbagai konteks budaya. Selain itu, perlu juga pengembangan metode kualitatif dan kuantitatif yang lebih inovatif untuk menganalisis data praktik sosial. Bayangin kayak lagi cari harta karun, masih banyak banget yang belum ketemu.

Mungkin aja ada penemuan baru yang bisa mengubah peta dunia ilmu sosial.

FAQ Section

What are some common criticisms of practice theory?

Critics often argue that practice theory struggles to fully account for large-scale social structures or adequately address power imbalances. Some also find the concept of “practice” itself too vague, making empirical testing challenging.

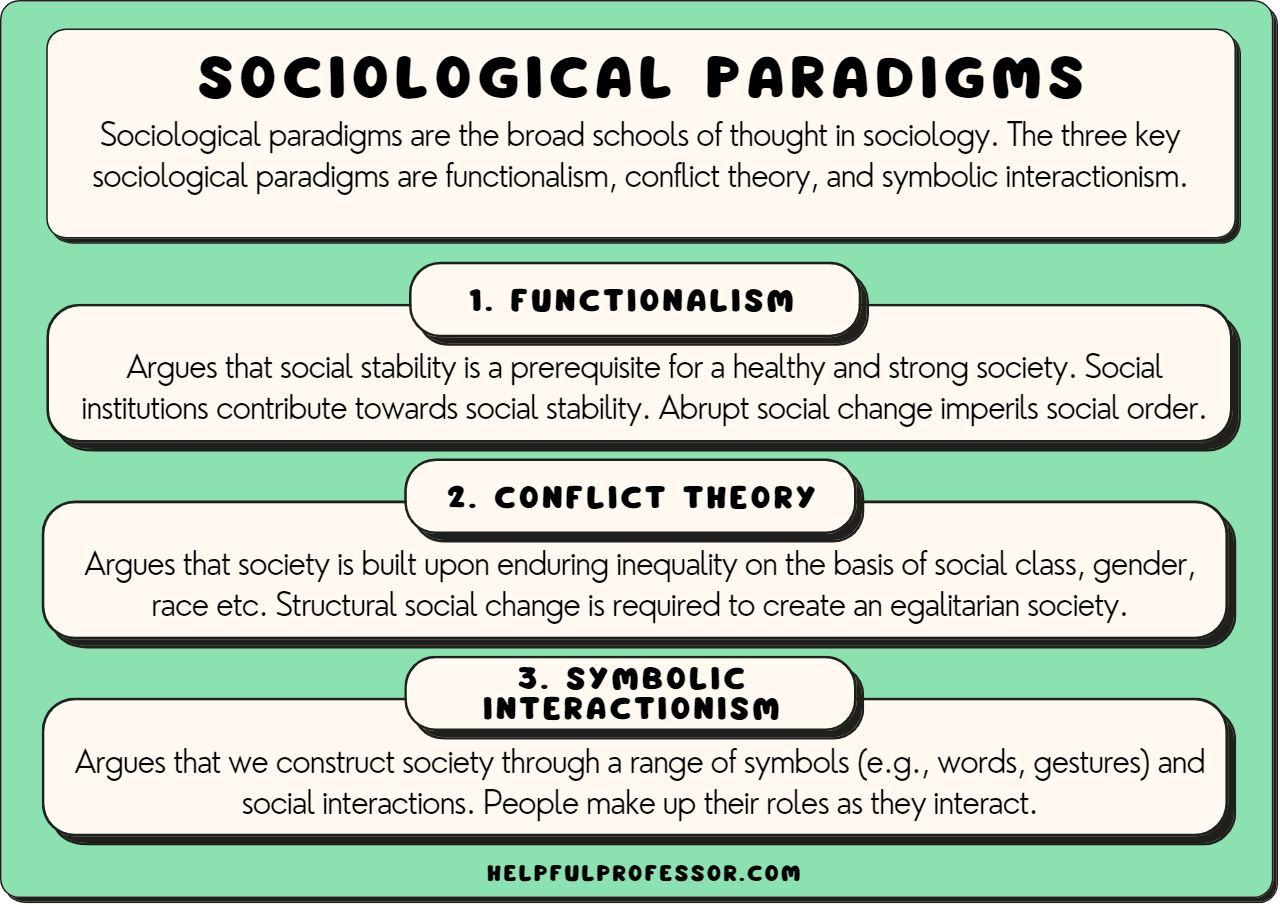

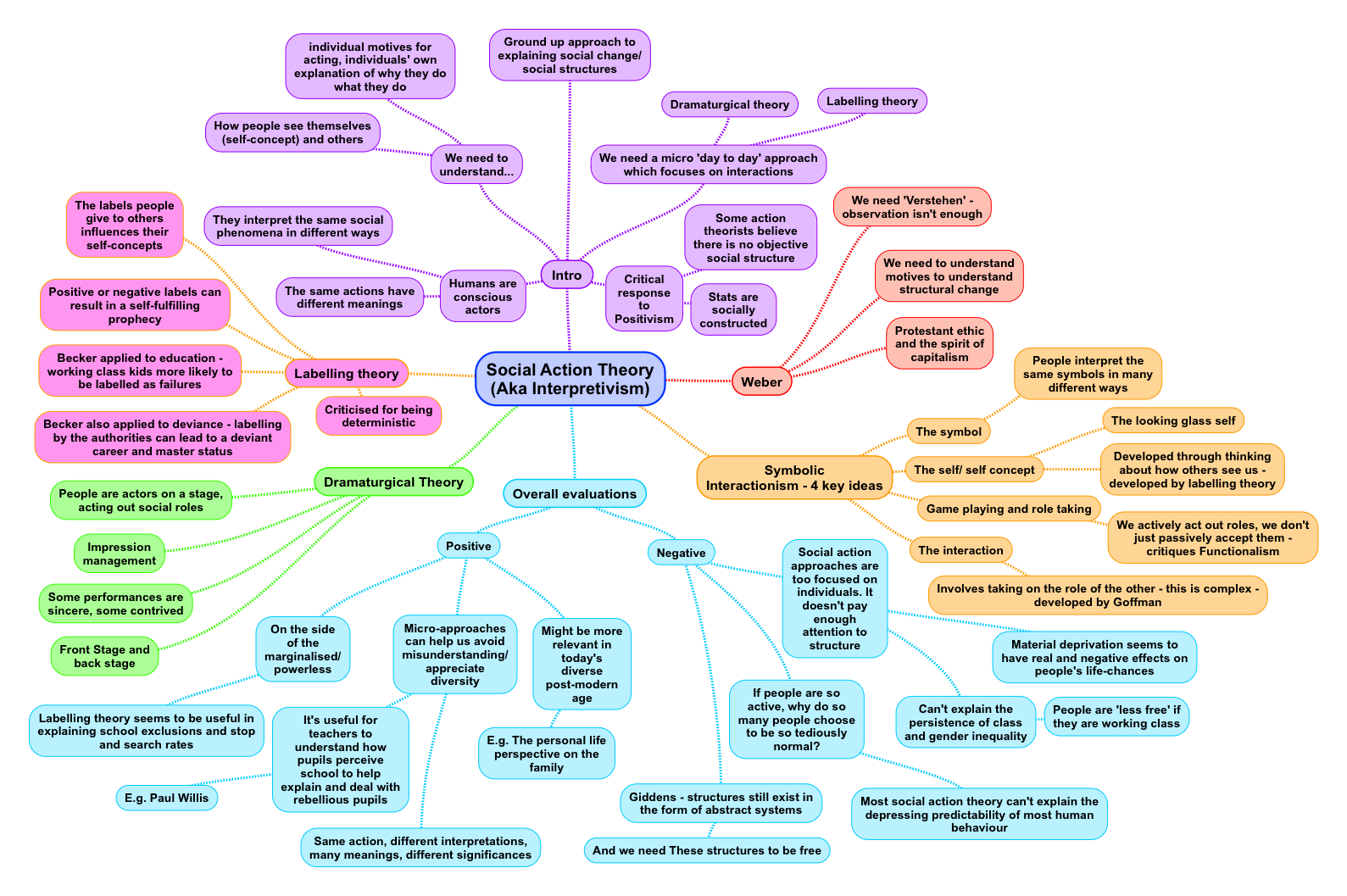

How does practice theory differ from symbolic interactionism?

While both focus on micro-level interactions, practice theory emphasizes the embeddedness of actions within broader social structures and historical contexts, whereas symbolic interactionism often focuses more on the construction of meaning through interaction itself.

Can practice theory be applied to the digital world?

Absolutely! Practice theory offers valuable insights into how digital technologies shape and are shaped by social practices, impacting everything from online communities to political mobilization.

How is practice theory used in policy-making?

Understanding social practices can inform policy interventions by highlighting how policies might unintentionally affect everyday actions and potentially lead to unintended consequences. It helps policymakers consider the real-world impact of their decisions on people’s daily lives.