What do dividers do in bowens theory of families – What do dividers do in Bowen’s theory of families? This crucial question delves into the heart of Bowenian Family Systems Therapy, exploring how various barriers – emotional, physical, or relational – impact family dynamics. Understanding these “dividers” is key to unlocking healthier family functioning, as they represent significant obstacles to intimacy, communication, and overall well-being. We’ll dissect the mechanisms behind these dividers, their categorization, and how Bowenian therapy tackles them.

Bowenian theory posits that families operate as interconnected systems, where each member’s actions influence the others. Dividers, therefore, aren’t merely individual issues but systemic problems affecting the entire family unit. From geographical distance to unspoken secrets, these barriers create emotional distance and hinder effective communication. This exploration will examine how these dividers manifest, their long-term consequences, and the therapeutic strategies employed to overcome them.

Introduction to Bowenian Family Therapy

Bowenian family therapy, developed by Murray Bowen, offers a unique perspective on family dynamics and their impact on individual well-being. Unlike other therapeutic approaches that focus primarily on individual symptoms, Bowenian therapy emphasizes the interconnectedness of family members and the multigenerational transmission of emotional patterns. This approach aims to increase each family member’s level of differentiation of self, leading to improved individual functioning and healthier family relationships.

Core Principles of Bowenian Family Therapy

The following table Artikels five core principles of Bowenian family therapy, along with illustrative case study examples.

| Principle | Explanation | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|

| Differentiation of Self | The ability to balance emotional and intellectual functioning; to separate thoughts and feelings. High differentiation allows individuals to maintain their identity within the family system. | A highly differentiated individual, Sarah, calmly discusses her concerns with her family despite their strong opinions, maintaining her own perspective. |

| Triangles | Two-person systems under stress often pull in a third person to stabilize the system. This creates a triangle, a three-person relational system. | In a family with marital conflict, the parents frequently involve their teenage son, drawing him into their arguments and creating a destabilizing triangle. |

| Nuclear Family Emotional System | The emotional patterns within a nuclear family (parents and children) that repeat across generations. These patterns often involve emotional reactivity and fusion. | A couple unconsciously replicates their parents’ conflict patterns, leading to similar arguments and emotional distance in their own marriage. |

| Multigenerational Transmission Process | The process by which emotional patterns and levels of differentiation are passed down through generations within a family. | Three generations of women in a family exhibit a pattern of anxiety and emotional reactivity, suggesting a multigenerational transmission of these traits. |

| Emotional Cutoff | Managing anxiety by reducing or eliminating contact with family members, often due to unresolved emotional issues. | John, struggling with unresolved anger toward his father, avoids all contact with his family, creating emotional distance. |

Differentiation of Self

Differentiation of self represents the capacity to balance emotional and intellectual functioning. Individuals with low differentiation are highly reactive to the emotions of others, often experiencing fusion (blurring of personal boundaries) within the family system. Conversely, those with high differentiation can think clearly and act independently, even under stress. The spectrum ranges from low (highly reactive, fused) to high (autonomous, self-aware).

Low differentiation is associated with higher anxiety levels within the family system, while high differentiation promotes emotional regulation and resilience. For instance, individuals with low differentiation might exhibit emotional reactivity, conflict avoidance, or a strong need for approval, whereas those with high differentiation might display assertiveness, emotional regulation, and clear boundaries.

The Family Systems Perspective in Bowenian Theory

Bowenian theory views the family as an emotional unit, where members are interconnected and influence one another’s behavior and emotional states. This interconnectedness is illustrated through several key concepts:* Triangles: A three-person system often forms when stress arises in a dyad (two-person relationship), drawing in a third person to alleviate tension.

Multigenerational Transmission Process

Emotional patterns and levels of differentiation are passed down through generations, shaping family dynamics and individual functioning.

Emotional Cutoff

Managing anxiety by reducing or eliminating contact with family members, often due to unresolved emotional issues. This flowchart depicts a simplified family system, showing how emotions and interactions flow between family members. Each circle represents a family member, lines represent relationships, and arrows illustrate the direction of emotional influence. This visualization helps to demonstrate the interconnectedness of the family system and the concept of multigenerational transmission.

Defining Dividers in Bowenian Theory

Bowenian Family Systems Theory emphasizes the interconnectedness of family members and how patterns of interaction influence individual functioning. A key concept within this framework is the presence of “dividers,” which represent barriers or obstacles that interfere with healthy family dynamics and individual well-being. Understanding the nature and impact of these dividers is crucial for effective Bowenian family therapy.

Detailed Description of “Dividers” in Bowenian Family Dynamics

In Bowenian Family Systems Theory, dividers are mechanisms that create emotional or physical distance between family members, hindering open communication and healthy emotional connection. They function as barriers to intimacy and prevent the family from functioning as a cohesive unit. These dividers aren’t necessarily intentional acts of sabotage; rather, they are often unconscious patterns of behavior, communication, or emotional responses that develop over time within the family system.

They stem from anxieties within the family, contributing to a less differentiated family system. The underlying mechanisms involve various communication patterns, emotional processes, and behavioral manifestations that perpetuate the distance and dysfunction. For instance, chronic conflict avoidance, rigid role assignments, and secrets all contribute to the creation and maintenance of dividers. These behaviors, in turn, reinforce the dysfunctional patterns within the family system.

Categorization and Examples of Dividers

The following table categorizes different types of dividers commonly observed in Bowenian family systems.

| Type of Divider | Description | Example | Impact on Family Functioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Distance | Geographic separation hindering regular interaction. | Family members living in different countries, resulting in infrequent visits and limited shared experiences. Another example would be a family member choosing to live in a remote location deliberately to avoid family interaction. | Reduced emotional intimacy, difficulty in crisis management, feelings of isolation and disconnection. In the second example, it could lead to resentment and further estrangement. |

| Emotional Distance | Lack of emotional connection and intimacy. | Chronic avoidance of emotional expression or vulnerability, resulting in superficial interactions and a lack of genuine empathy. Another example would be consistent use of sarcasm or criticism in place of direct emotional expression. | Increased conflict, feelings of isolation, difficulty in resolving conflicts, and a general lack of support. The second example creates further emotional distance and distrust. |

| Secret-Keeping | Concealing information from family members. | One sibling hiding a significant life event (e.g., a serious illness, a major life decision) from the rest of the family. Another example would be parents concealing financial difficulties from their children. | Erosion of trust, difficulty in problem-solving, feelings of betrayal and exclusion, and a breakdown in communication. In the second example, it could create anxiety and uncertainty for the children. |

| Rigid Roles | Family members adhering to inflexible roles that limit personal growth. | The “perfect child” role preventing self-expression and exploration of individual interests. Another example is the perpetually “sick” family member who uses illness to avoid responsibilities and maintain attention. | Stifled individuality, resentment, lack of autonomy, and difficulty in adapting to changing circumstances. The second example can create resentment in other family members and prevent the individual from achieving their full potential. |

| Substance Abuse | Use of drugs or alcohol creating distance and dysfunction. | A parent’s alcoholism leading to neglect and conflict. Another example would be a teenager’s drug use leading to secrecy and strained relationships with family members. | Instability, trauma, broken trust, financial problems, and potential for violence. The second example creates significant anxiety and potential danger for the family. |

| Chronic Criticism | Consistent negative and judgmental communication patterns. | One family member constantly criticizes another’s choices, appearance, or personality. Another example is a parent constantly criticizing a child’s achievements, even when they are significant. | Erosion of self-esteem, increased conflict, feelings of inadequacy, and avoidance of communication. The second example can lead to low self-esteem and resentment. |

Comparative Analysis of Divider Impacts

Physical distance, emotional distance, and secret-keeping, when compared, reveal distinct yet interconnected impacts. Physical distance limits opportunities for direct interaction, weakening emotional bonds. Emotional distance fosters a climate of disconnection, hindering open communication and support. Secret-keeping erodes trust and prevents collaborative problem-solving. For example, a family separated geographically (physical distance) might struggle to connect emotionally (emotional distance), leading to the concealment of important information (secret-keeping).

This combination of dividers exacerbates family dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle of isolation and mistrust. The presence of multiple dividers simultaneously creates a synergistic effect, amplifying the negative consequences. For instance, a family dealing with substance abuse (a divider) might also experience significant emotional distance and secret-keeping, resulting in severe dysfunction and potentially long-term trauma. Bowenian therapy addresses these dividers through techniques such as process questions to enhance self-awareness and improve communication, and detriangulation to reduce the intensity of conflict and promote healthier relationships.

Case Study Application

Consider a family where the father (John) is emotionally distant (emotional distance), rarely expressing feelings or engaging in meaningful conversations. Simultaneously, the family maintains a rigid role structure (rigid roles), with the mother (Mary) acting as the primary caregiver and emotional regulator, while the children are expected to maintain a facade of perfection. This emotional distance and rigid role structure contribute to the children’s feelings of isolation and inability to express their own needs.

The emotional distance prevents open communication and the expression of needs, while the rigid roles prevent individual growth and self-expression. A Bowenian therapist might utilize techniques such as family meetings to foster open communication and help family members understand their roles and their impact on the family system. The therapist might also work with each individual to improve their level of differentiation, helping them to manage their own emotions and develop healthier relationships.

This approach aims to reduce the impact of the dividers by promoting self-awareness, improving communication, and strengthening individual autonomy. The rationale behind these strategies is to increase the family’s overall level of differentiation, allowing for healthier emotional connections and improved family functioning.

The Role of Triangles in Bowenian Family Systems

Triangles are a fundamental concept in Bowenian Family Therapy, representing a crucial mechanism through which family systems maintain emotional distance and manage conflict. They are formed when a two-person system experiences tension or anxiety, drawing in a third person to stabilize the dyad, thus creating a three-person system. This process, while seemingly resolving immediate conflict, often serves to perpetuate dysfunctional patterns and reinforces existing family dividers.Triangles significantly contribute to the creation and maintenance of family dividers by diverting attention away from the underlying issues within the original dyad.

By introducing a third party, the original conflict becomes diffused, preventing direct confrontation and honest communication. This indirect approach prevents the resolution of underlying problems and solidifies emotional distance between family members. The inclusion of the third person also often leads to increased anxiety and conflict, as each member navigates their position within the triangle.

Triangles as Dividers: Mechanisms and Examples

The introduction of a triangle disrupts healthy communication and fosters emotional distance. For example, consider a couple experiencing marital conflict. Instead of directly addressing their issues, one partner might confide in a child, creating a triangle. The child, caught in the middle, may become anxious, loyal to one parent over the other, or develop behavioral problems as a result of the parental conflict being displaced onto them.

This process prevents the parents from resolving their conflict directly, thus reinforcing their emotional distance and creating a divider between the parents and the child, as well as between the parents themselves.Another example could involve a parent and a child forming a coalition against the other parent. This often manifests as a child siding with one parent in a marital dispute, creating a triangle that excludes the other parent.

The excluded parent then feels isolated and further divides the family unit. This triangulation pattern prevents open communication and the resolution of underlying marital problems. The child, instead of being nurtured in a healthy family environment, becomes embroiled in adult conflicts, impacting their emotional development and creating further divisions within the family.The process is not always malicious or intentional; it often arises unconsciously as a way to manage anxiety and avoid direct conflict.

However, the result remains the same: a dysfunctional triangle that reinforces emotional distance and hinders healthy family functioning, acting as a powerful divider within the family system. These triangles solidify the emotional distance and reinforce existing patterns of relating, preventing healthy communication and resolution of underlying issues.

Impact of Family Projection Process

Family projection, a key concept in Bowenian family therapy, significantly impacts the development of individuals within a family system. It describes the process by which parents displace their anxieties and unresolved emotional issues onto their children, influencing the child’s self-perception, relational patterns, and overall well-being. This process often creates and reinforces dividers within the family, leading to emotional distance and rigid boundaries.

Family Projection Process: Creation and Reinforcement of Dividers

The family projection process creates dividers through projective identification, a mechanism where parents unconsciously attribute their own unresolved conflicts and anxieties to their children. The child, in turn, internalizes these projections, shaping their behavior and self-perception to align with parental expectations. This can manifest in relational dynamics as a child acting out the parent’s anxieties, thus reinforcing the dysfunctional pattern.

For example, a parent struggling with anxiety might project their fear of failure onto their child, leading the child to become overly perfectionistic and self-critical. In nuclear families, this might involve the child becoming the “problem child,” absorbing the family’s anxiety. In extended families, the projection might target a specific child within a larger network, creating a rift. In blended families, step-parents might project anxieties onto stepchildren, creating conflict and distance.

Rigid boundaries and emotional distance are frequently observed as the child attempts to manage the parental projections, leading to isolation and a lack of genuine connection.

Impact of Parental Anxiety on the Creation and Maintenance of Dividers

Parental anxiety plays a crucial role in shaping the projective patterns and their consequences for children. Different types of anxiety lead to distinct ways of projecting onto children.

| Parental Anxiety Type | Projective Pattern | Impact on Child | Example Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Anxiety | Child becomes overly responsible, attempting to control the parent’s anxiety. | Child develops high levels of anxiety and difficulty with relaxation; struggles with autonomy. | A parent with generalized anxiety might constantly worry about their child’s safety and well-being, leading the child to become hyper-vigilant and avoid taking risks. |

| Separation Anxiety | Child becomes overly dependent and clingy, fearing abandonment. | Child develops difficulties with independence and forming healthy relationships; potential for codependency. | A parent with separation anxiety might excessively monitor the child’s whereabouts, leading to the child developing an intense fear of being alone or separated from the parent. |

| Social Anxiety | Child becomes withdrawn and socially isolated, mirroring the parent’s fear of social interaction. | Child develops social anxiety and difficulties forming and maintaining relationships; struggles with self-esteem. | A parent with social anxiety might avoid social events, leading the child to develop a similar avoidance pattern and fear of social situations. |

Family Projection and the Differentiation of Self in Children

Family projection significantly hinders the development of a child’s sense of self. The constant bombardment of parental projections makes it difficult for the child to discern their own thoughts, feelings, and needs from those imposed upon them. This prevents the development of autonomy and healthy boundaries. The child struggles to form a cohesive sense of self, independent of parental projections.

Long-term consequences include difficulties in adult relationships, characterized by codependency, emotional reactivity, and an inability to establish healthy boundaries. Potential coping mechanisms include therapy, self-reflection, and mindful practices to increase self-awareness and emotional regulation.

Role of Family Secrets and Unspoken Rules in Perpetuating Family Projection

Family secrets and unspoken rules act as powerful mechanisms for perpetuating the family projection process. These elements contribute to a climate of secrecy and emotional suppression, preventing open communication and creating a fertile ground for projection. Secrets, particularly those surrounding emotional trauma or dysfunction, can be projected onto children, who may unconsciously take on the role of carrying the family’s burden.

Unspoken rules, such as avoiding certain topics or expressing certain emotions, reinforce these patterns, preventing the child from developing a healthy understanding of their family dynamics and their own feelings. This lack of open communication further impacts the child’s self-perception, creating a sense of confusion and shame.

Impact of Family Projection on Children with Different Temperaments

The impact of family projection varies significantly depending on the child’s temperament and personality traits. Children with high resilience and strong coping mechanisms might be less affected by parental projections. Conversely, children with more sensitive temperaments or pre-existing vulnerabilities may be more susceptible to internalizing these projections. Genetic predisposition and environmental factors play a significant role in shaping the child’s response.

For instance, a child with a genetic predisposition towards anxiety might be more likely to internalize a parent’s anxious projections, leading to amplified anxiety symptoms. A supportive and nurturing environment, on the other hand, can buffer the child against the negative effects of family projection.

Therapeutic Interventions to Address Family Projection

Therapeutic interventions aimed at addressing the effects of family projection focus on helping individuals identify and challenge parental projections, establish healthier boundaries, and foster greater self-differentiation. Techniques such as Bowenian family therapy, which emphasizes improving family communication and reducing anxiety levels, are effective in disrupting projective patterns and promoting healthier family dynamics. Individual therapy can help individuals develop self-awareness, challenge internalized projections, and learn healthy coping mechanisms.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge the limitations of these interventions. Deeply ingrained projective patterns may require significant time and effort to overcome. Success often depends on the individual’s willingness to engage in self-reflection and make conscious changes in their relational patterns.

Intergenerational Transmission of Family Projection

Family projection often follows an intergenerational pattern, with projective patterns being passed down through generations. Parents who were subjected to family projection may unconsciously replicate these patterns in their own families. For example, a woman who experienced her mother’s projection of her anxieties might, in turn, project her own anxieties onto her children, creating a cyclical pattern of dysfunctional family dynamics.

This transmission of projective patterns influences the relational dynamics of subsequent families, perpetuating the cycle of emotional distress and hindering the development of healthy relationships.

Multigenerational Transmission Process and Dividers

Bowenian family therapy emphasizes the multigenerational transmission process, highlighting how family patterns and emotional processes are passed down through generations, significantly influencing the development and maintenance of family dividers. This transmission isn’t simply about inheriting genes; it’s about inheriting relational patterns, emotional responses, and coping mechanisms that shape individual and family functioning across time.The multigenerational transmission process contributes to the formation of persistent dividers by reinforcing specific relational dynamics.

These dynamics, often rooted in unresolved family issues, create recurring patterns of interaction that solidify emotional distance and limit the family’s capacity for intimacy and effective communication. These patterns can manifest as chronic conflict, emotional cutoff, or rigid hierarchies within the family system, all of which act as dividers, preventing open expression and healthy resolution of conflict.

Transmission of Family Patterns

Family patterns, including communication styles, conflict resolution strategies, and emotional regulation techniques, are learned within the family of origin. Children observe and internalize these patterns, often unconsciously replicating them in their own relationships and families. For instance, a family characterized by high levels of conflict and emotional volatility may produce children who struggle with managing their own emotions and resolving conflict constructively.

This leads to the continuation of similar patterns in subsequent generations, creating a cyclical process that maintains the family’s emotional distance and reinforces the presence of dividers.

Impact of Unresolved Emotional Issues

Unresolved emotional issues, such as trauma, grief, or unresolved conflict, significantly influence the multigenerational transmission process. These unresolved issues can manifest as anxiety, depression, or other emotional difficulties that are passed down through generations. For example, if a grandparent experienced significant trauma that was never adequately addressed, this trauma might manifest as anxiety or depression in their children and grandchildren, affecting their relational patterns and contributing to the formation of dividers within the family.

The family’s inability to process and resolve these emotional issues leads to the perpetuation of patterns of avoidance, emotional distance, and dysfunctional coping mechanisms, all of which act as dividers.

Linking Seemingly Unrelated Family Issues

The multigenerational transmission process demonstrates how seemingly unrelated family issues can be interconnected. What might appear as isolated problems – for instance, a child’s anxiety, a parent’s substance abuse, or a marital conflict – can be linked through a common thread of unresolved emotional issues or dysfunctional relational patterns originating in previous generations. These patterns create a chain reaction where one family member’s difficulties influence the functioning of others, contributing to the formation of persistent dividers.

For example, a parent’s unresolved grief from a past loss might manifest as emotional distance from their children, impacting the children’s ability to form healthy attachments and creating emotional dividers within the family. The anxiety or avoidance behaviors stemming from this emotional distance can then be passed down to subsequent generations.

Sibling Position and its Relation to Dividers

Sibling position significantly impacts individual experiences within the family system, influencing the development of self and the dynamics of relationships with parents and siblings. This, in turn, affects the creation and maintenance of family dividers, those emotional barriers that prevent open communication and connection within the family. Birth order is not deterministic, but it offers a framework for understanding how different positions within the sibling hierarchy contribute to these patterns.

Bowenian theory emphasizes the impact of family dynamics on individual functioning. Within this framework, the roles siblings assume, largely shaped by their birth order, influence how they interact with the family’s emotional system and how they contribute to or challenge existing dividers. Older siblings often take on more responsibility, potentially leading to increased anxiety and a heightened awareness of family tensions.

Younger siblings might experience different pressures, possibly feeling overlooked or overshadowed. These differing experiences contribute to the formation and reinforcement of family dividers, impacting the overall emotional health of the family system.

The Influence of Birth Order on Sibling Roles

The position of a child within the sibling hierarchy often dictates the roles they assume within the family. Firstborns, for example, often receive more focused parental attention initially, potentially leading to a stronger sense of responsibility and a more rigid adherence to family rules. Middle children may develop strong negotiation skills as they strive for parental attention and recognition amidst their siblings.

Youngest children may be more indulged or may develop a tendency to manipulate in order to gain attention. These varying experiences shape their individual approaches to conflict and communication within the family, directly affecting the presence and nature of family dividers. For example, a firstborn’s strong sense of responsibility might lead them to uphold family secrets, thus reinforcing a divider, while a youngest child’s manipulative tactics could challenge existing dividers by creating conflict and forcing a confrontation of underlying issues.

Sibling Roles in Reinforcing or Challenging Dividers

Siblings can play crucial roles in either reinforcing or challenging family dividers. Some siblings may actively contribute to maintaining emotional distance and secrecy, thereby strengthening existing dividers. This might involve tacit agreements to avoid certain topics or individuals within the family. In contrast, other siblings might actively challenge these dividers by seeking open communication, expressing their emotions, or attempting to bridge the gaps between family members.

Their efforts may lead to increased conflict, but ultimately can foster greater emotional connection and a reduction in the impact of family dividers. A sibling who consistently mediates between parents locked in conflict, for instance, is actively challenging a divider, while a sibling who avoids all discussions about a difficult family member is inadvertently reinforcing that divider.

Examples of Sibling Dynamics and Dividers

Consider a family with three children. The oldest, feeling responsible for the family’s well-being, might actively avoid conflict to maintain a semblance of order, thus reinforcing a divider around a contentious family secret. The middle child, feeling overlooked, might attempt to gain attention through rebellious behavior, challenging the divider by forcing a confrontation. The youngest child, witnessing the family tension, might withdraw emotionally, further reinforcing the existing divider through passive avoidance.

These distinct responses, all shaped by their birth order and individual experiences, contribute to the complex interplay of family dynamics and the presence or absence of emotional dividers within the family system.

In Bowenian family therapy, dividers represent the emotional distance family members maintain to manage anxiety. Think of it like this: the process of establishing that distance is akin to a sophisticated algorithm, much like the weak light relighting algorithm based on prior knowledge uses prior information to reconstruct an image. Just as the algorithm utilizes existing data, families use learned patterns of interaction to create emotional space, thereby influencing the overall family system’s functioning and ultimately, the effectiveness of these dividers in reducing anxiety.

Emotional Cutoff and its Connection to Dividers

Emotional cutoff, a key concept in Bowenian family therapy, represents a significant divider within family systems. It describes a process where individuals manage anxiety by reducing or eliminating contact with family members, thereby disrupting the flow of emotional connection and creating distinct emotional subsystems. This section will explore emotional cutoff in detail, examining its various forms, underlying mechanisms, consequences, and therapeutic interventions.

Emotional Cutoff Defined and its Manifestations

Emotional cutoff is defined as the process of reducing or eliminating emotional contact with one or more family members to manage anxiety and unresolved conflict. This distancing can manifest in various forms. Physical distance, such as moving far away geographically, represents one type. For example, a person might relocate to a different country to avoid interacting with their family of origin.

Emotional distance involves maintaining minimal emotional engagement despite geographical proximity. This might involve avoiding deep conversations or expressing feelings. Finally, communication avoidance encompasses strategies such as ignoring calls, emails, or social media messages to minimize interaction. A person might consistently decline invitations to family gatherings or events as a means of avoiding contact. Underlying these behaviors are often anxiety, fear of intimacy, and unresolved family conflicts that individuals find overwhelming or threatening to manage.

This differs from other forms of family distancing, such as healthy boundary setting, which prioritizes self-care without severing emotional ties. Healthy boundaries acknowledge the need for personal space and autonomy, but do not actively avoid engagement or communication.

Emotional Cutoff as a Family System Divider

Emotional cutoff significantly disrupts the family’s emotional system. By severing emotional connections, it creates distinct emotional subsystems, preventing the free flow of anxiety and information within the family. This disruption impacts intergenerational transmission processes, hindering the healthy transmission of family patterns and hindering the ability to learn from past experiences. The cutoff prevents the resolution of past conflicts and creates a cycle of unresolved issues.For example, consider a family where a daughter (Sarah) emotionally cuts off from her highly critical mother (Martha).

This creates two distinct subsystems: Sarah’s, characterized by emotional isolation, and Martha’s, marked by feelings of rejection and resentment. This division prevents the family from addressing the underlying issues contributing to the conflict and disrupts the family’s overall functioning. The emotional cutoff prevents the family from working together to solve problems and can increase conflict in other relationships within the family.

| Characteristic | Families with Emotional Cutoff | Families without Emotional Cutoff |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Frequency | Infrequent, often strained or superficial | Frequent, open, and honest |

| Communication Style | Avoidant, indirect, or hostile | Direct, assertive, and respectful |

| Boundary Permeability | Rigid, inflexible, and poorly defined | Flexible, adaptable, and clearly defined |

Consequences of Emotional Cutoff

Emotional cutoff carries significant consequences for both individuals and the family system. Individuals may experience emotional isolation, difficulty forming intimate relationships, and impaired self-differentiation. They may struggle with identity formation and lack a strong sense of self. For the family, consequences include increased conflict, reduced cohesion, impaired problem-solving abilities, and a perpetuation of dysfunctional patterns across generations. The long-term effects can impact subsequent generations, potentially leading to similar patterns of emotional distancing and relationship difficulties.Potential therapeutic interventions for addressing emotional cutoff include:

- Improving family communication and conflict resolution skills.

- Enhancing self-differentiation in individual family members.

- Facilitating increased empathy and understanding between family members.

- Addressing underlying unresolved issues and conflicts.

- Promoting healthier boundary setting and emotional regulation.

Case Study Analysis

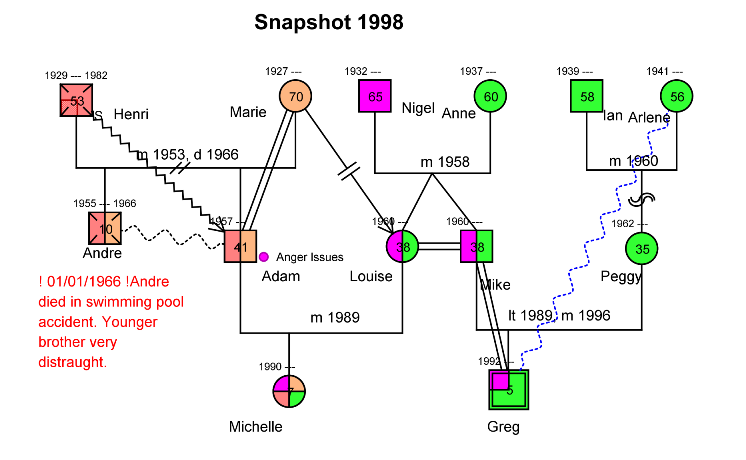

Consider the Miller family. A three-generation genogram reveals that the grandmother (Eleanor) experienced significant emotional neglect from her own parents. This led to a pattern of emotional withdrawal and avoidance of intimacy. Her daughter, Susan, mirrored this pattern, emotionally cutting off from Eleanor due to unresolved resentment stemming from perceived criticism and lack of emotional support. Susan, in turn, maintains limited contact with her own daughter, Jessica, primarily communicating through infrequent text messages.

Susan’s emotional cutoff stems from her own experiences of emotional unavailability and a fear of repeating her mother’s patterns. This has resulted in Jessica feeling emotionally abandoned and struggling to form close relationships. The overall impact on the family system is a lack of emotional cohesion, hindering their ability to support one another. Therapeutic interventions might involve family therapy sessions focusing on improving communication, addressing past hurts, and enhancing each member’s self-differentiation.

Comparative Analysis of Bowenian Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Mechanisms | Consequences | Therapeutic Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Cutoff | Reducing or eliminating emotional contact with family members | Anxiety, fear of intimacy, unresolved conflict | Emotional isolation, impaired relationships, dysfunctional family patterns | Improving communication, enhancing self-differentiation, addressing unresolved issues |

| Triangulation | Involving a third person to reduce anxiety in a dyadic relationship | Anxiety in a two-person relationship | Increased conflict, impaired communication, dysfunctional alliances | Detriangulation, improving communication within the dyad |

| Fusion | Lack of differentiation between self and others | Low self-differentiation, enmeshment | Loss of identity, impaired autonomy, conflict | Enhancing self-differentiation, establishing healthy boundaries |

The Function of Dividers in Maintaining Family Equilibrium

Dividers, in Bowenian family therapy, are patterns of behavior or emotional distance that prevent close emotional connection within a family system. While seemingly disruptive, these dividers can paradoxically serve a crucial function in maintaining a perceived sense of stability and equilibrium within the family, albeit often at a significant cost. Understanding this function is key to unraveling the complexities of dysfunctional family dynamics.Families utilize dividers to manage stress and conflict by creating emotional distance between members.

This distance can prevent the escalation of conflict and protect individuals from the intense emotional reactivity that can characterize highly enmeshed family systems. The dividers effectively buffer the family from overwhelming emotional turmoil, creating a false sense of calm.

Examples of Dividers Maintaining Family Equilibrium

Families employ various strategies to create these emotional buffers. For instance, a family might rely on one member consistently taking on the role of the “scapegoat,” absorbing the family’s anger and conflict, thereby preventing it from directly impacting other relationships. This allows the remaining family members to maintain a facade of harmony, even if it’s built upon the suffering of one individual.

Another example involves physical distance. A child who moves far away to attend college or pursue a career might unconsciously use this geographical separation as a divider to manage unresolved family conflicts or anxieties related to their family of origin. Similarly, a couple might engage in chronic arguing or silent treatment, creating a consistent emotional distance that prevents deeper connection and potential conflict escalation, thus maintaining a predictable (though unhealthy) family dynamic.

Negative Consequences of Relying on Dividers for Family Stability

While dividers offer a temporary sense of stability, their long-term consequences are often detrimental. The reliance on dividers prevents genuine emotional intimacy and connection within the family. The scapegoat, for instance, may experience significant emotional distress and isolation. The use of physical distance as a divider can lead to feelings of loneliness and alienation, hindering the development of healthy relationships.

Chronic conflict or emotional withdrawal, as dividers, prevents the family from addressing underlying issues and resolving conflicts constructively. This unresolved tension can manifest in various ways, including mental health issues, relationship problems, and difficulties in personal growth for individual family members. Furthermore, the false sense of stability created by dividers prevents the family from developing the emotional maturity and flexibility needed to navigate life’s inevitable challenges effectively.

The reliance on these dysfunctional coping mechanisms perpetuates a cycle of unhealthy interaction patterns, potentially impacting future generations.

Identifying and Addressing Dividers in Therapy: What Do Dividers Do In Bowens Theory Of Families

Identifying and addressing family dividers in Bowenian family therapy requires a nuanced understanding of the family system’s dynamics and the therapist’s role in facilitating change. The process involves careful observation, skillful questioning, and targeted interventions aimed at improving differentiation and reducing emotional reactivity.

A step-by-step approach to identifying family dividers involves initially assessing the overall family functioning. This includes observing interaction patterns, listening for recurring themes and conflicts, and noting who consistently aligns against whom. The therapist then focuses on identifying specific relational patterns that maintain distance and prevent emotional connection. This might involve mapping out family relationships, tracing the history of significant conflicts, and exploring individual family members’ experiences of emotional cutoff or triangulation.

Identifying Family Dividers Through Observation and Inquiry

The therapist begins by observing family interactions during therapy sessions. This includes paying close attention to nonverbal cues like body language and tone of voice, as well as the content of their conversations. Specific questions are posed to elicit information about family history, relational patterns, and individual experiences. For instance, the therapist might ask about significant events that created division within the family, such as a major illness, divorce, or death.

They may also explore the history of specific family alliances and rivalries, and how these have impacted individual family members’ emotional well-being. The goal is to identify recurring patterns of interaction that consistently separate certain family members from others.

Therapeutic Interventions to Reduce the Impact of Family Dividers

Once family dividers are identified, therapeutic interventions focus on increasing self-differentiation among family members. This process involves helping individuals develop a stronger sense of self and a greater capacity for emotional regulation. Interventions might include:

- Improving Communication Skills: Teaching family members effective communication techniques, such as active listening and expressing emotions constructively, can help to reduce misunderstandings and conflict.

- Promoting Emotional Awareness: Helping family members identify and understand their own emotions and the emotions of others is crucial for breaking down emotional barriers.

- Encouraging Self-Reflection: Facilitating individual reflection on personal patterns of relating and reacting can help family members understand their role in maintaining the family’s division.

- Reframing Family Narratives: Challenging negative or overly simplistic narratives about family relationships can help to create a more balanced and nuanced understanding of the family’s history.

These interventions aim to help family members move away from rigid, polarized positions and toward greater empathy and understanding.

The Therapist’s Role in Overcoming Family Divisions

The therapist plays a crucial role in helping families overcome these divisions. They act as a neutral observer, facilitating open communication and challenging dysfunctional patterns. The therapist helps family members understand how their individual behaviors contribute to the overall family dynamic and how these behaviors perpetuate the dividers. They also provide support and guidance as family members work towards greater self-awareness and improved relationships.

Crucially, the therapist maintains a non-judgmental stance, creating a safe space for family members to explore their feelings and experiences without fear of criticism or blame. They also help family members develop strategies for managing conflict constructively and building healthier relationships. This often involves teaching techniques for managing anxiety and emotional reactivity, as these are often key components in maintaining family dividers.

Case Study: The Miller Family

The Miller family, consisting of parents Robert and Susan, and their two teenage children, Emily (16) and David (14), presents a compelling case study illustrating the impact of dividers within a Bowenian family system. Years of unresolved conflict and emotional distancing have created significant barriers to open communication and healthy emotional connection.

Family Dynamics and Dividers

Robert and Susan, both high-achievers in their respective careers, have always prioritized professional success. This has inadvertently led to a pattern of emotional detachment within the family. Robert, known for his stoicism, avoids expressing vulnerability, creating a divider between himself and his children. Susan, while more emotionally available, often mediates conflicts by siding with one child against the other, inadvertently reinforcing divisions.

Emily, the older child, acts as the responsible one, taking on adult-like responsibilities, creating a divider between herself and her parents. She feels burdened by the family’s emotional needs. David, the younger child, has withdrawn into himself, becoming increasingly isolated and defiant. His rebellious behavior functions as a divider, creating distance from both parents and his sister. The family’s reliance on avoidance and unspoken resentments contributes to a cycle of emotional distance and conflict.

Impact on Individual Family Members

Emily experiences significant stress from her role as the responsible child, leading to anxiety and difficulty forming peer relationships. She feels unseen and unheard by her parents. David’s emotional withdrawal has resulted in poor academic performance and increased risk-taking behaviors. He feels misunderstood and rejected by his family. Robert experiences chronic stress from work and the emotional distance within his family, resulting in health issues and limited emotional expression.

Susan, despite her attempts to mediate, feels overwhelmed and burdened by the family’s dysfunction, experiencing feelings of inadequacy and helplessness.

Potential Consequences of Unaddressed Dividers

If these dividers remain unaddressed, the consequences for the Miller family could be severe. Emily’s stress could manifest in more serious mental health challenges. David’s risk-taking behaviors could escalate, potentially leading to legal trouble or substance abuse. Robert and Susan’s emotional detachment could lead to marital discord and further estrangement from their children. The family could experience continued conflict and lack of cohesion, potentially resulting in long-term emotional damage and fractured relationships.

Ultimately, failure to address these dividers could lead to significant individual and family dysfunction.

Impact of Societal Influences on Family Dividers

Societal forces exert a profound influence on family structures and dynamics, often contributing significantly to the creation and reinforcement of Bowenian family dividers. These external pressures shape individual beliefs, values, and behaviors, impacting the ways families interact and manage conflict. Understanding these influences is crucial for effective Bowenian family therapy.

Economic Disparity and Family Dividers

Economic inequality significantly impacts family dynamics, often leading to the development of dividers. Wealth disparities create unequal access to resources, opportunities, and social capital, fostering resentment and tension within families. For example, a family where one sibling receives extensive financial support for higher education while another struggles to afford basic necessities may experience significant division. This disparity can manifest as covert or overt conflict, with siblings distancing themselves emotionally or engaging in open arguments about fairness and resource allocation.

The resulting resentment can persist for generations, creating lasting divides within the family system.

Religious and Spiritual Differences as Dividers

Differing religious or spiritual beliefs within a family can be a major source of conflict and division. Fundamental disagreements on moral values, life choices, or interpretations of sacred texts can lead to strained relationships and emotional distance. For instance, a family where one member converts to a different religion may experience significant tension and alienation from other family members who hold strong traditional beliefs.

In Bowenian family therapy, dividers represent the emotional distance individuals create to manage anxiety within the family system. Understanding these emotional processes helps us grasp the complexities of family dynamics, much like trying to understand why someone might leave a long-term project, such as Matt’s departure from Game Theory, as explained in this insightful article: why is matt leaving game theory.

Ultimately, both situations – the creation of emotional dividers and the decision to leave a collaborative endeavor – stem from a need for individual autonomy and emotional regulation within a complex system.

These differences can lead to unspoken resentments, avoidance of certain topics, or even outright estrangement, creating a significant divider within the family system.

Political Polarization and its Impact on Family Relationships

The increasing political polarization in many societies significantly impacts family relationships. Deeply held and often opposing political views can create divisions that extend beyond simple disagreements. For instance, families may find themselves sharply divided over issues such as immigration, climate change, or social justice, leading to heated arguments and strained communication. These divisions can escalate into avoidance, emotional cutoff, or even complete estrangement, functioning as powerful dividers within the family system.

The intensity of these divisions is often amplified by the emotionally charged nature of political discourse in the media and social networks.

Cultural Norms and Family Dynamics: A Cross-Cultural Comparison

Cultural norms and expectations play a significant role in shaping family structures and the formation of dividers. Examining these norms across different cultures provides valuable insights into the diverse ways societal pressures manifest within families.

Japanese Culture and Family Dividers

In Japanese culture, strong emphasis on maintaining harmony and avoiding direct conflict often leads to families employing indirect communication strategies. This can result in unspoken resentments and unspoken family secrets that act as hidden dividers. The hierarchical structure of traditional Japanese families, with a strong emphasis on respect for elders, can also create divisions between generations. Younger family members might feel stifled by expectations of obedience and conformity, leading to emotional distance and a lack of open communication.

American Culture and Family Dividers

In contrast to Japanese culture, American culture often values individualism and open expression. While this can facilitate open communication, it can also lead to conflict and division when family members hold differing views. The emphasis on personal achievement and independence can create competition and rivalry among siblings, fostering resentment and division. Furthermore, the high mobility rate in American society can lead to geographical separation and reduced family interaction, contributing to the development of emotional cutoff as a form of divider.

Case Studies Illustrating Societal Influences on Family Dividers, What do dividers do in bowens theory of families

The following case studies illustrate how societal pressures influence family patterns and the use of dividers:

Case Study 1: The Garcia Family

The Garcia family, originally from Mexico, experienced significant economic hardship after immigrating to the United States. The pressure to adapt to a new culture and secure financial stability created tension between parents and children. The children, feeling the weight of their parents’ struggles, developed a sense of responsibility that created a divide between them and their peers. The parents, in turn, felt a sense of guilt and inadequacy, leading to emotional withdrawal.

The long-term consequence is a family characterized by unspoken resentments and limited emotional intimacy.

Case Study 2: The Jones Family

The Jones family experienced significant division due to differing political beliefs. The father, a staunch conservative, and the mother, a progressive liberal, engaged in frequent and heated arguments about political issues. Their children, caught in the middle, adopted polarized positions, further exacerbating the family conflict. This resulted in limited family gatherings and emotional distancing, with children avoiding discussions about politics with their parents.

Case Study 3: The Lee Family

The Lee family, a Korean-American family, faced challenges due to conflicting cultural values. The parents held traditional Korean values, emphasizing filial piety and respect for elders. However, their children, raised in American society, embraced more individualistic values. This clash of cultural expectations created a significant generational divide, resulting in misunderstandings, conflict, and emotional distance.

Table of Societal Factors and their Impact

| Societal Factor | Impact on Family Dynamics | Example of Manifestation as Divider |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Inequality | Creates unequal access to resources and opportunities, fostering resentment and tension. | Siblings experiencing vastly different levels of financial support for education. |

| Religious Differences | Leads to conflict over moral values, life choices, and interpretations of sacred texts. | Estrangement due to a family member converting to a different religion. |

| Political Polarization | Creates deep divisions over political ideologies and issues, leading to heated arguments and avoidance. | Family members refusing to discuss politics due to sharply contrasting views. |

| Generational Differences | Leads to misunderstandings and conflict due to differing values, beliefs, and experiences. | Conflict between parents who value tradition and children who embrace modern values. |

| Technological Advancements | Impacts communication patterns and family interaction, potentially leading to isolation and emotional distance. | Increased screen time leading to decreased face-to-face interaction and emotional connection. |

The most significant societal influences on family dividers include economic inequality, religious and spiritual differences, and political polarization. These factors create deep divisions within families, impacting communication patterns, emotional intimacy, and overall family functioning. Understanding the interplay between these societal pressures and family dynamics is crucial for effective intervention and promoting healthier family relationships.

The Role of Differentiation of Self in Overcoming Family Dividers

Differentiation of self, a core concept in Bowenian family therapy, plays a crucial role in navigating and overcoming the divisive patterns that often characterize family systems. A high level of differentiation empowers individuals to manage emotional reactivity, establish healthy boundaries, and ultimately foster healthier family relationships. Conversely, low differentiation often contributes to the perpetuation of family conflict and emotional cutoff.

High Differentiation and Family Dynamics

High differentiation of self significantly impacts an individual’s emotional reactivity within a dysfunctional family system. Individuals with a high level of differentiation possess a strong sense of self, allowing them to think clearly and act independently even under pressure from family members. They are less likely to be emotionally reactive or entangled in family conflicts. For example, an individual with high differentiation might calmly address a critical family member, setting clear boundaries about acceptable behavior without engaging in emotional escalation.

They can acknowledge the family member’s feelings without internalizing the criticism. This contrasts sharply with individuals with low differentiation, who might react defensively, become overly anxious, or engage in self-blame. Emotional cutoff, a common response to intense family conflict, is less likely in highly differentiated individuals, as they are better equipped to manage difficult emotions and maintain healthy relationships while setting appropriate limits.

They might choose to limit contact with particularly challenging family members but do so consciously, not out of emotional reactivity or fear.

Boundary Setting in High and Low Differentiation

Individuals with high differentiation set and maintain healthy emotional boundaries. These boundaries are characterized by clear communication, assertive behavior, and a respect for both personal needs and the needs of others. In contrast, individuals with low differentiation often have blurred boundaries, leading to emotional reactivity and a struggle to assert their needs.

| Boundary Strategy | High Differentiation | Low Differentiation |

|---|---|---|

| Responding to Criticism | Calmly assesses the criticism, selectively responds to valid points, and sets limits on unacceptable behavior. For instance, they might say, “I understand you’re upset, but I don’t appreciate being blamed.” | Reacts emotionally, internalizes criticism, and seeks approval. They might apologize excessively or try to change their behavior to please the critic, even if it compromises their own values. |

| Managing Conflict | Addresses conflict directly, respectfully, and assertively, focusing on solutions rather than blame. They might say, “Let’s discuss this calmly. What can we do to resolve this?” | Avoids conflict, placates, or engages in passive aggression. They might withdraw from the conversation or make sarcastic remarks instead of addressing the issue directly. |

| Emotional Expression | Expresses feelings appropriately, without reactivity. They can clearly state their feelings without attacking others. For example, “I feel hurt when you say that.” | Has difficulty expressing feelings, is overly reactive, or suppresses feelings altogether. They might explode emotionally or become silent and withdrawn. |

| Maintaining Independence | Maintains personal values and goals despite family pressure. They can respectfully disagree with family members without feeling guilty or abandoning their own identity. | Adjusts personal values and goals to please family members, often neglecting their own needs and desires. They might feel obligated to conform to family expectations, even if they are personally unhappy. |

Self-Reflection and Awareness

Self-reflection and awareness are crucial for increasing differentiation. Techniques like journaling and mindfulness can help individuals identify their emotional responses to family members and understand the patterns of their interactions. One effective technique is mindful self-reflection journaling.

Mindful Self-Reflection Journaling: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Choose a quiet time and space: Find a time when you can be free from distractions for at least 15-20 minutes.

- Set an intention: Before you begin, focus on your intention for this journaling session. For example, “I want to understand my emotional reactions to my mother’s criticism.”

- Recall a recent interaction: Think back to a recent interaction with a family member that triggered a strong emotional response. Describe the interaction in detail.

- Identify your emotions: Name the specific emotions you experienced during the interaction (e.g., anger, sadness, anxiety). Be as precise as possible.

- Explore the roots of your emotions: Reflect on why you experienced those emotions. What thoughts or beliefs contributed to your feelings? Consider past experiences or family patterns that might be influencing your reactions.

- Observe without judgment: Practice observing your thoughts and emotions without judgment. Simply acknowledge them without trying to change them.

- Identify your needs: What did you need in that interaction? What could have been done differently?

- Reflect on your responses: How did you respond to the situation? Was your response effective? What would you do differently next time?

- Practice self-compassion: Be kind and understanding towards yourself. Recognize that you are doing your best to navigate complex family dynamics.

Identifying Family Patterns

Identifying recurring patterns of interaction and communication within the family system is essential. These patterns often contribute to conflict and dysfunction. For example, a family might consistently engage in triangulation, where one member pulls in a third party to mediate a conflict between two others. Another common pattern is the family projection process, where parental anxieties are projected onto a child.

Recognizing these patterns allows individuals to understand their role in perpetuating them and to develop strategies for breaking free from them.

Developing Assertiveness Skills

Developing assertive communication skills is crucial for establishing healthy boundaries. Assertiveness involves expressing needs and boundaries clearly and respectfully without aggression or passivity. For instance, instead of passively accepting criticism, an assertive individual might say, “I understand your concerns, but I disagree with your assessment.” Instead of aggressively confronting a family member, they might say, “I need some time to process this before we discuss it further.”

Seeking Professional Support

Seeking professional help, such as therapy or counseling, can significantly improve differentiation of self, particularly in high-conflict families or situations involving significant emotional distress. A therapist can provide guidance, support, and tools to help individuals develop self-awareness, improve communication skills, and establish healthy boundaries.

Long-Term Effects of Family Dividers on Individual Well-being

Family dividers, those unspoken rules and patterns of relating within a Bowenian family system, exert a significant and often long-lasting impact on individual well-being. These dividers, while seemingly innocuous or even protective in the short term, can create significant psychological and emotional consequences that ripple across generations. Understanding these long-term effects is crucial for effective intervention and promoting healthier family dynamics.The presence of unresolved family dividers can manifest in a variety of ways, significantly affecting various aspects of an individual’s life.

These effects extend beyond immediate family relationships, impacting career choices, romantic partnerships, and overall life satisfaction. The emotional burden carried from a family system characterized by significant dividers can lead to chronic stress, anxiety, and depression. This stress can manifest physically as well, contributing to various health problems.

Impact on Relationships

Unresolved family dividers often create difficulties in forming and maintaining healthy relationships. Individuals who grew up in families with significant dividers may struggle with intimacy, communication, and conflict resolution. They may unconsciously replicate the dysfunctional patterns learned in their family of origin, leading to repetitive cycles of conflict and emotional distance in their adult relationships. For example, someone who experienced emotional cutoff within their family of origin might struggle to establish close, trusting relationships as an adult, fearing intimacy or repeating the pattern of disconnection.

Alternatively, individuals might seek out partners who unconsciously reinforce familiar dysfunctional patterns, creating a sense of familiarity, albeit a painful one.

Impact on Career and Life Satisfaction

The pervasive influence of family dividers can extend to career choices and overall life satisfaction. Individuals burdened by unresolved family issues may experience difficulty in setting and achieving professional goals. The chronic stress and anxiety associated with unresolved family dynamics can impact job performance, leading to decreased productivity and job dissatisfaction. Similarly, the lack of emotional regulation and healthy coping mechanisms often associated with families characterized by significant dividers can negatively impact an individual’s ability to experience joy and fulfillment in life.

They might find themselves constantly seeking external validation or struggling to find meaning and purpose in their work or personal life.

Intergenerational Transmission of Family Dividers

The impact of family dividers is not limited to the individuals who directly experience them. These dysfunctional patterns often transmit across generations, influencing the relationships and well-being of subsequent family members. Children raised in families with significant dividers may internalize these patterns, repeating them in their own families and relationships. For example, if a parent experienced emotional cutoff from a parent, they might unconsciously replicate this pattern with their own children, leading to similar emotional distance and disconnection.

This intergenerational transmission perpetuates the cycle of dysfunctional family dynamics, creating a lasting legacy of unresolved conflict and emotional distress. The effects can be subtle, manifesting as seemingly inexplicable anxieties or relational patterns that seem to defy logical explanation.

Therapeutic Techniques for Addressing Family Dividers

Addressing family dividers effectively requires a multifaceted approach, utilizing techniques that foster differentiation of self, unravel emotional triangles, and address multigenerational patterns. Bowenian family therapy offers a rich framework for understanding and resolving these issues, emphasizing the interconnectedness of family members and their impact on individual functioning. The following techniques are commonly employed to promote healthier family dynamics and reduce the negative influence of dividers.

Ten Therapeutic Techniques for Addressing Family Dividers

The following list details ten therapeutic techniques, each with a description and application within the Bowenian framework. These techniques aim to improve communication, reduce conflict, and foster greater self-awareness within the family system.

- Process Questions: These questions encourage family members to reflect on their thoughts and feelings, promoting self-awareness and understanding of their emotional responses within the family system. This helps identify patterns of interaction contributing to family dividers, such as chronic conflict or secrets. For example, asking “What are you thinking and feeling right now as you hear your sister’s perspective?” can help clarify emotional responses and break down defensive barriers.

- Genograms: Visual representations of family history across multiple generations, illuminating recurring patterns and themes. Genograms help to identify multigenerational transmission processes and recurring family dividers, such as unresolved grief or substance abuse. By mapping family dynamics across generations, therapists can pinpoint areas needing attention.

- Detriangulation: Helping individuals step out of emotionally charged triangles (parent-child alliances against another parent) to reduce conflict and promote healthier relationships. This is particularly useful in addressing dividers stemming from parental conflict or favoritism. For instance, guiding a child to express their feelings directly to the parent rather than using a sibling as a messenger can help.

- Differentiation of Self Exercises: Activities designed to increase self-awareness and emotional regulation, enabling individuals to make choices based on their own values rather than reacting to family pressures. This directly tackles the root of many dividers by reducing reactivity and improving communication. Journaling about emotional responses to family situations is one example.

- Family Sculpting: A nonverbal technique where family members physically arrange themselves to represent their perception of family relationships. This can reveal hidden tensions, alliances, and patterns contributing to family dividers such as emotional cutoff or unresolved trauma. The physical arrangement provides a powerful visual representation of relational dynamics.

- Reframing: Reinterpreting family dynamics and behaviors to highlight adaptive functions or underlying needs. This helps to lessen the impact of negative patterns and allows for a more constructive perspective on family dividers, such as sibling rivalry viewed as competition for attention.

- Emotional Cutoff Reduction: Strategies to encourage healthier communication and connection with estranged family members, thereby resolving unresolved conflicts and reducing the impact of emotional distance. This directly addresses dividers stemming from past hurts or unresolved issues.

- Focusing on Individual’s Needs: Encouraging each family member to express their individual needs and concerns. This approach fosters empathy and understanding within the family, mitigating dividers caused by unmet needs or unresolved conflicts. It can be used to address parental favoritism by highlighting the needs of each child.

- Role-Playing: Practicing different communication styles and responses to family conflicts in a safe and controlled environment. Role-playing allows family members to experiment with new behaviors and develop more effective coping mechanisms for resolving conflicts and addressing dividers such as chronic conflict.

- Goal Setting and Contract Development: Establishing clear, achievable goals for improved family functioning and creating a contract outlining agreed-upon behaviors and expectations. This provides a framework for change and accountability, reducing the impact of various family dividers by focusing on positive outcomes.

Comparison of Therapeutic Approaches to Family Dividers

The following table compares and contrasts four distinct therapeutic approaches in their application to family dividers.

| Technique Name | Core Principles | Application to Family Dividers | Limitations/Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowenian Family Therapy | Differentiation of self, multigenerational transmission process, emotional triangles | Addresses family dividers by increasing self-awareness, improving communication, and resolving emotional triangles; e.g., using process questions to uncover underlying patterns in sibling rivalry. | Can be lengthy and may not be suitable for families experiencing acute crisis or severe dysfunction. |

| Structural Family Therapy | Family structure, boundaries, hierarchies | Addresses family dividers by restructuring family boundaries and hierarchies; e.g., establishing clearer boundaries to reduce parental conflict contributing to a child’s anxiety. | May be less effective in addressing deeply ingrained emotional patterns or intergenerational trauma. |

| Strategic Family Therapy | Problem-solving, communication patterns, behavioral change | Addresses family dividers by focusing on specific behavioral changes and communication strategies; e.g., using paradoxical directives to address a pattern of avoidance in a family with secrets. | May not address the underlying emotional issues contributing to family dividers. |

| Narrative Therapy | Externalizing problems, creating alternative stories | Addresses family dividers by helping families re-author their stories and create more positive narratives; e.g., reframing intergenerational trauma as a story of resilience rather than victimhood. | May not be suitable for families with limited insight or those resistant to self-reflection. |

Examples of Therapeutic Techniques in Action

Below are examples illustrating the practical application of each technique in a family session.

- Process Questions: A therapist asks a parent, “When your son criticizes you, what are you feeling, and how does that impact your interactions with him?” This helps the parent understand their emotional reactions and their role in the conflict.

- Genograms: A therapist uses a genogram to show a family that a pattern of substance abuse has existed across three generations, helping them understand the multigenerational transmission process contributing to their current struggles.

- Detriangulation: A therapist helps a child communicate directly with their parent instead of using a sibling as a mediator, thereby reducing the emotional triangle and improving direct communication.

- Differentiation of Self Exercises: A therapist guides a family member to journal about their emotional reactions to family conflicts, helping them become more aware of their emotional responses and develop strategies for self-regulation.

- Family Sculpting: A family physically arranges themselves to represent their relationships; the arrangement reveals a hidden alliance between two siblings against a parent, highlighting a key family divider.

- Reframing: A therapist reframes sibling rivalry as a sign of each child’s desire for attention and connection, shifting the family’s perception from negative competition to unmet needs.

- Emotional Cutoff Reduction: A therapist encourages a family member to write a letter to a distant relative, initiating communication and working towards resolving past hurts.

- Focusing on Individual Needs: A therapist guides each family member to express their needs, revealing that parental favoritism stems from one parent’s unmet emotional needs.

- Role-Playing: A family practices assertive communication techniques to address conflict, improving their ability to express their needs and resolve disagreements.

- Goal Setting and Contract Development: A family collaboratively sets goals for improved communication and creates a contract outlining specific behaviors to achieve these goals.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are paramount when working with families experiencing significant conflict or trauma. The following points highlight potential challenges.

- Maintaining confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from all family members.

- Addressing potential power imbalances within the family system.

- Avoiding coercion or pressure to participate in therapy.

- Recognizing and managing potential therapist bias or countertransference.

- Ensuring cultural sensitivity and awareness.

- Setting clear boundaries and limits within the therapeutic relationship.

- Referring to other professionals when necessary (e.g., child protective services).

- Prioritizing the safety and well-being of all family members.

Summary of Therapist Self-Awareness and Countertransference Management in Family Therapy

Effective family therapy hinges on the therapist’s self-awareness and ability to manage countertransference. Countertransference, the therapist’s unconscious emotional reactions to the family, can significantly impact the therapeutic process. A therapist’s own family history and unresolved issues can unconsciously influence their perceptions and interactions with the family. Regular supervision, self-reflection, and ongoing professional development are crucial for maintaining objectivity and providing effective, ethical care.

By acknowledging and managing their own emotional responses, therapists can avoid projecting their personal experiences onto the family and create a safe and supportive therapeutic environment. This self-awareness allows therapists to identify and address their own biases, ensuring that their interventions are appropriate and beneficial for the family.

Flowchart for Selecting Therapeutic Techniques

A flowchart depicting the decision-making process for selecting therapeutic techniques is omitted due to the limitations of this text-based format. However, the process would involve assessing the family’s presenting problem, identifying key family dividers, considering the family’s strengths and resources, and selecting techniques tailored to the specific needs and dynamics of the family system.

Bibliography

A bibliography of scholarly articles supporting the chosen therapeutic techniques and their application within Bowenian family therapy is omitted due to the limitations of this text-based format. However, a comprehensive literature review on Bowenian family therapy and its application to various family issues would be readily available through academic databases such as PsycINFO and PubMed.

Essay: Effectiveness of Techniques in Promoting Long-Term Family Well-being

The effectiveness of Bowenian therapeutic techniques in fostering long-term family well-being and resilience is demonstrably significant, although success hinges on various factors including family commitment, therapist skill, and the nature of the family’s challenges. Techniques like process questions facilitate increased self-awareness, a cornerstone of Bowen’s theory, enabling family members to understand their emotional responses and relational patterns contributing to conflict.