What component creates racial formation theory? It’s a question that unravels a complex tapestry woven from social structures, power dynamics, and the very construction of race itself. This exploration delves into the heart of how racial categories are formed and maintained, revealing the intricate interplay of institutions, ideologies, and individual actions. We’ll uncover how seemingly disparate elements—from housing policies to media representations—contribute to a system that shapes our understanding of race and its profound consequences.

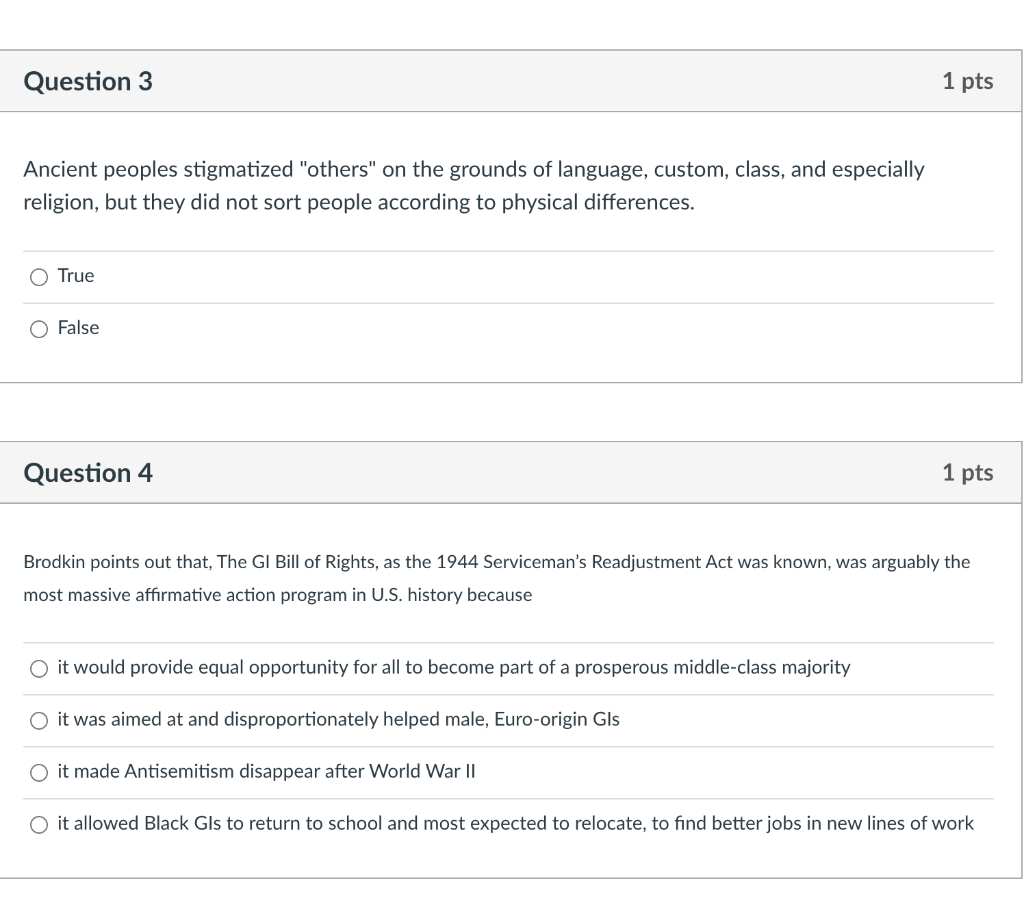

Racial formation theory, pioneered by Omi and Winant, posits that race isn’t a biological reality but a social construct, constantly evolving through “racial projects.” These projects are the mechanisms—the very components—that create and reinforce racial categories. They encompass everything from overt acts of discrimination to subtle biases embedded within institutions. By examining the historical context, analyzing key social structures, and exploring the role of ideology and discourse, we’ll gain a deeper appreciation for the multifaceted nature of racial formation and its enduring impact on society.

Defining Racial Formation Theory

Racial formation theory, developed by Michael Omi and Howard Winant, offers a powerful framework for understanding how race is constructed and operates within society. It moves beyond static notions of race as a biological reality, instead emphasizing the dynamic and fluid nature of racial categories and their role in shaping social relations and power structures. The theory highlights the interplay between social structures and individual agency in the ongoing creation and transformation of racial meanings.Racial formation theory posits that race is not a fixed or natural entity, but rather a social construct that is constantly being created and recreated through social processes.

Its core tenets revolve around the concept of racial projects, which are simultaneous processes of signifying racial meanings and enacting those meanings through social structures and institutions. These projects are not simply individual actions, but rather involve collective efforts to define racial boundaries, allocate resources along racial lines, and establish systems of racial hierarchy. The theory emphasizes the role of power in shaping these racial projects, arguing that dominant groups use their power to maintain racial hierarchies and shape racial meanings to their advantage.

This dynamic process is not limited to overt acts of discrimination, but also operates through seemingly neutral social structures and institutions that perpetuate racial inequalities.

Core Tenets of Racial Formation Theory

Racial formation theory rests on several key concepts. First, it emphasizes the social construction of race, rejecting biological explanations of racial difference. Second, it highlights the role of racial projects in shaping racial meanings and social structures. Third, the theory underscores the interconnectedness of race and power, demonstrating how racial hierarchies are maintained and reproduced through social institutions and practices.

Fourth, it stresses the fluidity and changeability of racial categories over time and across different social contexts. Finally, the theory acknowledges the agency of individuals and groups in negotiating and resisting racial classifications and structures, demonstrating that racial formation is not a deterministic process.

Historical Context of Racial Formation Theory

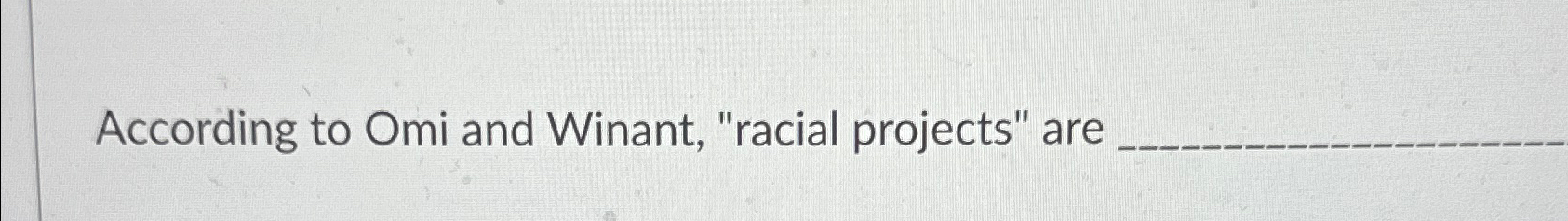

Racial formation theory emerged in the late 20th century, during a period of significant social and political change in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Power challenged existing racial hierarchies and prompted a reassessment of conventional understandings of race. Existing theories of race often failed to adequately explain the persistence of racial inequality despite legal advancements.

Omi and Winant’s work offered a new perspective, emphasizing the ongoing process of racial formation and the need to analyze race as a social and political phenomenon, rather than a purely biological or individual matter. The theory was also influenced by the growing body of scholarship on social constructionism and the sociology of knowledge, which highlighted the role of social processes in shaping our understanding of the world.

Racial Formation Theory Compared to Other Racial Theories

Unlike essentialist theories of race, which view race as a fixed and inherent characteristic of individuals, racial formation theory emphasizes the socially constructed nature of race. It differs from biological theories, which attempt to explain racial differences through genetics, by focusing on the social processes that create and maintain racial categories. Furthermore, in contrast to theories that focus solely on individual prejudice or discrimination, racial formation theory examines the broader social structures and institutions that perpetuate racial inequalities.

It also distinguishes itself from theories that prioritize either structure or agency by acknowledging the interplay between the two. For example, while acknowledging the structural power of racism embedded in institutions, it also recognizes the agency of individuals and groups in contesting and shaping racial meanings and social relations. This nuanced approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities of race and racism in society.

The Role of Social Structures

Racial formation theory posits that race is not a biological reality but a social construct, constantly being created and recreated through social structures and processes. Understanding the role of these structures is crucial to analyzing how racial inequalities are produced and maintained. The following sections examine key social structures in the United States that have shaped racial formation, particularly during the 20th century.

Key Social Structures Contributing to Racial Formation in the 20th Century United States

Several key social structures significantly contributed to racial formation in the United States during the 20th century. These include the legal system, the economic system, the political system, and the educational system. These structures were not independent entities but rather interconnected and mutually reinforcing, creating and perpetuating racial hierarchies.

- Legal System: Jim Crow laws in the South legally enforced segregation and disenfranchisement of African Americans. Examples include poll taxes, literacy tests, and “separate but equal” facilities which were demonstrably unequal. These laws, coupled with discriminatory enforcement of existing legislation, created a system of racial oppression deeply embedded in the legal framework.

- Economic System: Redlining, a discriminatory practice by which banks and insurance companies refused mortgages and other services in predominantly Black neighborhoods, severely limited economic opportunities for African Americans. This created a cycle of poverty and limited access to wealth-building opportunities. Furthermore, discriminatory hiring practices and wage gaps further exacerbated economic inequalities.

- Political System: Voter suppression tactics, gerrymandering, and limited political representation systematically excluded African Americans from the political process. This meant their voices and concerns were consistently marginalized in policy decisions directly affecting their lives. The absence of political power further reinforced their subordinate status within society.

- Educational System: Segregated schools in the South provided vastly unequal educational resources to Black students, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage that impacted future economic and social mobility. Even after desegregation, unequal funding and resource allocation in many schools continued to disadvantage minority students.

Power Structures and the Creation and Maintenance of Racial Categories (1945-1980)

Between 1945 and 1980, economic, political, and legal power structures intersected and reinforced each other to maintain racial categories and inequalities. The post-World War II economic boom largely bypassed African Americans, who faced continued discrimination in employment and housing. Politically, while the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, significant resistance from powerful actors, including state and local governments, slowed progress and maintained existing power structures.

The legal system, while undergoing reforms, still allowed for discriminatory practices through loopholes and unequal enforcement of laws. For example, while legally segregation was outlawed, de facto segregation continued through practices like redlining and discriminatory housing policies. This resulted in a continued racial hierarchy despite the progress made during the Civil Rights era.

Institutional Perpetuation of Racial Inequalities During and After the Civil Rights Era

Specific institutions played a significant role in perpetuating racial inequalities.

- Southern Education System: Even after Brown v. Board of Education, massive resistance and slow implementation of desegregation led to continued unequal educational opportunities for Black students. This included inadequate funding, underqualified teachers, and inferior facilities in predominantly Black schools. This directly impacted the educational attainment and future economic prospects of African Americans.

- Law Enforcement Practices in Urban Areas: Racial profiling, excessive force, and discriminatory arrests disproportionately targeted African Americans, contributing to mass incarceration and reinforcing negative stereotypes. This contributed to the creation of a criminal justice system that disproportionately impacted minority communities.

- Housing Market: Redlining and discriminatory lending practices continued even after the Fair Housing Act of 1968, restricting access to homeownership and wealth accumulation for many Black families. This perpetuated residential segregation and created disparities in property values and neighborhood resources. The lasting effects of this can still be seen in the wealth gap between white and Black families today.

Impact of Social Structures on Racial Formation (1965-2000)

| Social Structure | Specific Policy/Practice | Impact on Racial Inequality | Supporting Evidence ||—|—|—|—|| Education | Unequal school funding and resource allocation | Perpetuated achievement gaps and limited educational attainment for minority students. | Kozol, J. (1991).

Savage inequalities

Children in America’s schools*. Crown Publishers; Oakes, J. (1985).

Keeping track

How schools structure inequality*. Yale University Press. || Housing | Redlining and discriminatory lending practices | Limited access to homeownership and wealth accumulation for minority communities, contributing to wealth inequality. | Rothstein, R. (2017).

The color of law

A forgotten history of how our government segregated America*. Liveright; Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993).

American apartheid

Segregation and the making of the underclass*. Harvard University Press. || Criminal Justice System | Racial profiling and discriminatory sentencing | Led to mass incarceration and disproportionate imprisonment of minority groups, further exacerbating existing inequalities. | Alexander, M. (2010).

The new Jim Crow

Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness*. The New Press; Pettit, B., & Western, B. (2004). Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race, crime, and incarceration in the United States.

- Annual Review of Sociology*,

- 30*, 457-480. |

Media Representations and Racial Formation (1960-1990)

Media representations during this period significantly shaped public perceptions of race. Newspapers often perpetuated stereotypes through biased reporting, focusing on crime and poverty in Black communities while neglecting positive stories and achievements. Television and film frequently portrayed stereotypical representations of Black individuals, reinforcing negative images and contributing to racial prejudice. For example, the limited and often stereotypical portrayals of African Americans in mainstream media reinforced negative perceptions and contributed to the perpetuation of racial inequalities.

The lack of diverse representation in leading roles further marginalized minority communities.

Comparing the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements

The Civil Rights and Black Power movements, while both aiming to achieve racial equality, differed significantly in their strategies. The Civil Rights Movement primarily employed nonviolent resistance and legal challenges to achieve integration and equal rights. The Black Power movement, on the other hand, emphasized Black self-determination, Black pride, and sometimes more confrontational tactics. While both movements achieved significant successes in challenging racial inequality, the Black Power movement’s focus on community empowerment and self-reliance addressed the systemic nature of racism more directly, though its more confrontational approach also faced limitations in terms of broad public support.

Social structures, not biological components, create racial formation theory; it’s a social construct, not a genetic one. Understanding the mechanisms of heredity, however, is crucial; the question of whether does translation in protein synthesis support the theory of evolution sheds light on the biological processes themselves, but doesn’t define the social overlay of race. Therefore, returning to the core point, the driving force behind racial formation remains the ever-shifting landscape of social power dynamics.

Intersectionality and Racial Formation

Intersectionality highlights how race intersects with other social categories, such as gender, class, and sexuality, to shape individual experiences. For example, a Black woman faces unique forms of discrimination based on the intersection of her race and gender, experiencing both racism and sexism. This complexity complicates simplistic understandings of racial formation, demonstrating that social structures create intersecting forms of oppression.

Ongoing Effects of Historical Social Structures

The legacy of historical social structures continues to shape contemporary racial inequalities. Redlining, for example, continues to impact housing wealth disparities today, as neighborhoods historically subjected to redlining remain economically disadvantaged. Similarly, mass incarceration, stemming from discriminatory law enforcement practices, has devastating consequences for individuals, families, and communities, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and inequality. This illustrates the concept of systemic racism, where discriminatory practices are embedded within social institutions, creating and perpetuating racial disparities across generations.

The Significance of Race as a Social Construct

Race, a concept central to racial formation theory, is not a biological reality but a social construct. This means that racial categories are not based on inherent, fixed biological differences, but rather on socially defined meanings and classifications that vary across time and place. While biological differences exist among individuals, the ways in which these differences are categorized and imbued with social significance are products of social processes, not inherent properties of human biology.The arbitrary nature of racial categories is evident in their historical fluidity.

The very definition of what constitutes a “race” has shifted dramatically across different societies and historical periods. For example, the concept of “whiteness” in the United States has evolved significantly over time, encompassing different groups at various points in history, demonstrating its constructed nature. Similarly, the boundaries between racial groups are not static; individuals and groups may be reclassified based on social and political circumstances.

Examples of Shifting Racial Categories

The historical fluidity of racial categories can be illustrated through various examples. In the United States, individuals of Irish, Italian, and Jewish descent were once considered non-white, yet are now generally categorized as white. This demonstrates how social and political factors, such as economic status and assimilation, can influence the classification of individuals into racial groups. In Brazil, a far more nuanced system of racial classification exists, recognizing a wider spectrum of racial identities than the binary black/white system prevalent in the United States.

This highlights the variability of racial categories across different societies and their dependence on culturally specific understandings. Conversely, the concept of “mixed race” has evolved, with increasing recognition and acceptance of multiracial identities, reflecting changes in social attitudes and legal frameworks.

Comparing the Social Construction of Race with Other Social Constructs

The social construction of race can be understood in comparison to other social constructs, such as gender and class. Like race, gender and class are not based on fixed biological realities, but rather on socially defined roles, expectations, and hierarchies. Gender categories, for instance, vary across cultures and historical periods, demonstrating that they are socially constructed, rather than biologically determined.

Similarly, class divisions are not solely determined by economic factors, but also by social and cultural factors that shape perceptions and interactions. All three – race, gender, and class – are fluid, dynamic, and subject to change, reflecting the power of social forces in shaping individual identities and social relations. They are all systems of categorization that create social hierarchies and inequalities, albeit through different mechanisms and with different consequences.

The common thread is the arbitrary nature of their defining characteristics and their ability to shape social interactions and power dynamics.

The Impact of Racial Projects

Racial formation theory posits that race is not a fixed biological reality but a social construct constantly shaped and reshaped through social, political, and economic processes. Central to this ongoing process are “racial projects,” which are the mechanisms through which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and destroyed. Understanding the impact of these projects is crucial to comprehending the persistent inequalities and power dynamics within society.

Defining Racial Projects

A concise definition of “racial projects” for a high school audience: Racial projects are ways that society assigns meaning to race, influencing how people are treated and how they see themselves. These projects can be intentional or unintentional, and they affect everything from where people live to the jobs they can get.For a university-level sociology course, a more nuanced definition is needed: Racial projects are simultaneous processes of signification and social structure.

Signification refers to the meaning given to racial categories (e.g., associating blackness with criminality). Social structure involves the ways these meanings are embedded in institutions and practices (e.g., discriminatory policing and sentencing). These projects are not merely individual acts of prejudice but are deeply embedded within systems of power and control.

Examples of Historical and Contemporary Racial Projects

The following table illustrates historical and contemporary examples of racial projects across various societal sectors. The analysis provided highlights the enduring nature of racial inequalities and their evolving manifestations.

| Category | Historical Example | Contemporary Example | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing & Segregation | Redlining in the United States, where banks systematically denied mortgages and other financial services to residents of specific neighborhoods, largely based on race. | Gentrification, which displaces long-term residents, often minority communities, due to rising property values and the influx of wealthier individuals. | Both redlining and gentrification demonstrate how housing policies and practices have historically and continue to reinforce racial segregation and economic inequality. Redlining created a legacy of disinvestment in minority communities, while gentrification exacerbates existing disparities by pricing out lower-income residents. |

| Education | The “separate but equal” doctrine, which legally sanctioned racially segregated schools in the United States, resulting in vastly unequal educational resources and opportunities. | Persistent achievement gaps between racial and ethnic groups, fueled by disparities in school funding, teacher quality, and access to resources. | While legal segregation has been abolished, its legacy continues to manifest in the form of unequal educational opportunities. Funding disparities and implicit biases within the education system perpetuate these inequalities. |

| Employment | Jim Crow laws and discriminatory hiring practices that systematically excluded African Americans and other minority groups from certain jobs and industries. | Implicit bias in hiring and promotion processes, leading to underrepresentation of minority groups in higher-paying and more prestigious positions. | While overt discrimination is now illegal, implicit biases continue to operate subtly yet powerfully, hindering the advancement of minority individuals in the workplace. While anti-discrimination laws exist, their effectiveness is limited by the subtle and often unconscious nature of these biases. |

| Criminal Justice | Mass incarceration of African Americans following the “War on Drugs,” characterized by harsher sentencing and discriminatory policing practices. | Racial profiling and sentencing disparities, where individuals from minority groups are disproportionately targeted, arrested, convicted, and receive harsher sentences than their white counterparts. | Media representations often reinforce negative stereotypes about minority groups, contributing to biases within the criminal justice system. This contributes to a cycle of disproportionate arrests, convictions, and incarceration. |

The Impact of Racial Projects on Individual Identities and Social Relations

Racial projects profoundly shape both individual identities and social relations.Individual Identities: Racial projects influence self-perception and self-esteem by shaping the social contexts in which individuals develop their racial identities. Members of marginalized groups may internalize negative stereotypes, leading to diminished self-esteem, while members of dominant groups may develop a sense of entitlement and privilege. For example, the constant exposure to negative media portrayals of a particular racial group can lead to the internalization of negative self-images by individuals within that group.

Conversely, dominant groups may benefit from positive portrayals that reinforce their social status. Individuals negotiate their identities through various strategies, such as resistance, assimilation, or code-switching, depending on the specific racial project and the individual’s social context.Social Relations: Racial projects create and reinforce social hierarchies and power dynamics, manifesting in everyday interactions, institutional structures, and political discourse. Language and media play a significant role in shaping perceptions and reinforcing racial hierarchies.

Stereotypes perpetuated through language and media can lead to prejudice and discrimination, impacting access to resources and opportunities. For example, the use of coded language in political discourse can subtly reinforce racial biases without explicitly mentioning race. Institutional structures, such as discriminatory hiring practices or biased criminal justice systems, further solidify these inequalities.

Analysis of Gentrification as a Racial Project

Gentrification, the process of renovating and improving a deteriorated urban neighborhood, often displaces long-term, lower-income residents, disproportionately impacting minority communities. This process represents a contemporary racial project, perpetuating existing inequalities. The influx of wealthier residents often leads to increased property values, forcing out those who can no longer afford to live in their homes. This displacement not only disrupts established social networks and community ties but also exacerbates existing economic disparities.

The loss of affordable housing options forces many families to relocate to less desirable neighborhoods, potentially impacting access to quality education, employment opportunities, and other essential resources. The social fabric of the community is torn apart, leading to feelings of displacement, anger, and resentment. Further research should investigate the effectiveness of policies designed to mitigate the negative consequences of gentrification, such as inclusionary zoning or community land trusts, and explore alternative models of urban revitalization that prioritize the needs of existing residents.

The Influence of Ideology and Discourse

Racial formation theory emphasizes the crucial role of ideology and discourse in shaping racial understandings and maintaining racial hierarchies. These are not simply reflections of biological differences but rather actively constructed through social processes, including the dissemination of specific beliefs, values, and narratives through various channels, most notably media and language. The interplay of these elements creates and reinforces racial categories, ultimately impacting social structures and individual experiences.Ideologies and discourses surrounding race are powerful tools used to justify social inequalities and maintain power structures.

They operate at both the individual and collective levels, shaping perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors related to race. These ideologies are often implicit, ingrained within cultural norms and practices, making them difficult to identify and challenge.

Key Ideologies and Discourses Shaping Racial Understandings

Dominant ideologies frequently portray certain racial groups as inherently superior or inferior, often based on pseudoscientific justifications that have historically been used to legitimize systems of oppression such as slavery, colonialism, and apartheid. These ideologies are perpetuated through narratives that emphasize differences in intelligence, morality, or work ethic, attributing these perceived differences to inherent racial characteristics rather than acknowledging the significant impact of social and economic factors.

For example, the historical discourse surrounding Black inferiority in the United States, fueled by racist ideologies, served to justify the institution of slavery and subsequent discriminatory practices. Conversely, ideologies promoting racial purity or superiority have been used to justify eugenics programs and other forms of discriminatory policies. These ideologies, though often explicitly challenged today, continue to subtly influence social perceptions and interactions.

Media Representations and the Formation of Racial Categories

Media, encompassing television, film, advertising, and the internet, plays a significant role in shaping racial categories and reinforcing existing stereotypes. Media representations often reflect and perpetuate dominant ideologies, creating and reinforcing negative stereotypes about certain racial groups while simultaneously idealizing others. For instance, the underrepresentation of certain racial groups in leadership roles or the overrepresentation of specific groups in roles associated with criminality contribute to the formation of prejudiced beliefs and attitudes.

The subtle and pervasive nature of these representations makes them particularly effective in shaping public perceptions and influencing social attitudes towards different racial groups. Moreover, the lack of diversity in media ownership and production further exacerbates this issue, limiting the range of perspectives and narratives that are presented.

The Role of Language in Constructing and Maintaining Racial Hierarchies

Language is not merely a neutral tool for communication; it actively participates in the construction and maintenance of racial hierarchies. The use of racial slurs and derogatory terms serves to dehumanize and marginalize targeted groups, reinforcing power imbalances. Even seemingly neutral language can subtly reinforce racial biases, such as the use of terms that implicitly associate certain racial groups with negative attributes or the absence of language to adequately represent the diversity of racial experiences.

The way language is used to describe and categorize individuals and groups reflects and reinforces existing social hierarchies, shaping perceptions and influencing interactions. For example, the historical use of euphemisms to describe slavery and segregation reflects the way language has been used to sanitize and normalize oppressive practices.

The Dynamics of Racial Power

Racial power, as understood within the framework of racial formation theory, is a complex interplay of individual actions and systemic structures that perpetuate racial inequality. It manifests in both overt and subtle ways, shaping social relations, institutional practices, and individual life chances. Understanding these dynamics requires analyzing how power operates at multiple levels and across various societal institutions.

Racial Power at Individual and Systemic Levels

Racial power operates simultaneously at individual and systemic levels, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle of inequality. At the individual level, racial power manifests through microaggressions—everyday slights, insults, and indignities—and interpersonal biases that affect interactions between individuals of different races. For instance, a white person clutching their purse tighter when a Black person approaches them demonstrates individual-level racial power through a nonverbal microaggression.

This seemingly small act reflects and reinforces broader societal stereotypes and anxieties. Similarly, implicit biases, which are unconscious associations between racial groups and negative traits, can lead to discriminatory behavior in hiring, lending, and other contexts. At the systemic level, racial power is embedded in institutions and policies that systematically disadvantage certain racial groups. Redlining, for example, a discriminatory practice where banks refused to provide mortgages to residents in certain neighborhoods, often those with predominantly Black populations, created lasting economic disparities.

Similarly, discriminatory lending practices, like charging higher interest rates to borrowers from minority groups, perpetuate economic inequality across generations. These systemic patterns are deeply entrenched and require significant effort to dismantle.

Comparison of Forms of Racial Power

Different forms of racial power exist, each with its unique characteristics and mechanisms of maintenance.

| Form of Racial Power | Description | Examples | Mechanisms of Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominance | The exertion of control and authority by a dominant racial group over subordinate groups. This often involves the use of force, coercion, and the creation of legal and social structures that maintain inequality. | Slavery in the United States, Apartheid in South Africa, Jim Crow laws in the American South. | Legal frameworks, institutional discrimination, social norms, media representations perpetuating stereotypes. |

| Resistance | Active opposition to dominant racial power structures. This can take many forms, from individual acts of defiance to large-scale social movements. | The Civil Rights Movement in the United States, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, Black Lives Matter. | Collective action, mobilization, legal challenges, cultural production that challenges dominant narratives. |

| Accommodation | Adaptation to dominant racial power structures, often involving the acceptance of subordinate status to avoid conflict or maintain access to resources. | Internalized racism, the adoption of behaviors and attitudes that conform to dominant expectations, participation in systems that perpetuate inequality. | Social pressure, economic necessity, fear of reprisal, lack of alternative options. |

| Subversion | Undermining dominant racial power structures through subtle or indirect means. This can involve challenging norms, reinterpreting symbols, or creating alternative spaces and communities. | The use of coded language in protest songs, the creation of counter-narratives in literature and art, the establishment of independent community organizations. | Strategic ambiguity, cultural production, building alternative networks and institutions. |

Mechanisms of Racial Power Maintenance Across Institutions

Racial power is maintained and reproduced through various mechanisms operating across different societal institutions.

Education

- Unequal resource allocation: Schools in predominantly minority communities often receive less funding, resulting in inadequate facilities, fewer resources, and lower teacher quality.

- Tracking and ability grouping: These practices can disproportionately place minority students in lower-level classes, limiting their academic opportunities.

- Implicit bias in teacher evaluations: Unconscious biases can influence teacher perceptions of students’ abilities, leading to differential treatment and lower expectations for minority students.

Law Enforcement

- Racial profiling: The targeting of individuals based on their race or ethnicity, leading to disproportionate arrests and convictions.

- Excessive force: The disproportionate use of force by law enforcement against minority communities.

- Bias in sentencing and prosecution: Racial disparities in sentencing and prosecutorial decisions, leading to harsher penalties for minority offenders.

Media

- Stereotypical representations: The portrayal of minority groups in negative or stereotypical ways, reinforcing harmful biases and prejudices.

- Underrepresentation: The lack of diversity in media ownership, production, and content, resulting in limited representation of minority perspectives.

- News coverage bias: The framing of news stories in ways that reinforce negative stereotypes or downplay the experiences of minority communities.

Case Study: The Tulsa Race Massacre

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre serves as a powerful illustration of the interplay between individual and systemic racial power. Individual acts of violence and prejudice, fueled by racial hatred and anxieties, ignited the massacre. Systemic racial inequalities, including the historical disenfranchisement and economic marginalization of Black residents, created the conditions that allowed the violence to escalate. The destruction of the Greenwood district, a thriving Black community, was a direct consequence of both individual actions and systemic structures of racial power.

The subsequent lack of accountability and historical erasure further illustrate the enduring power of systemic racism.

Intersectionality and Racial Power

Intersectionality, a framework developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, highlights how race intersects with other social categories such as gender, class, and sexuality to shape experiences of power and oppression. A Black woman, for example, faces unique forms of discrimination based on the intersection of her race and gender. She experiences both racism and sexism, which often reinforce and amplify each other.

Similarly, a working-class Latino immigrant may experience discrimination based on their race, class, and immigration status, creating complex and overlapping forms of marginalization.

Challenging and Resisting Racial Power

Individuals and groups employ various strategies to challenge and resist racial power. These include activism, legal challenges, cultural production, and community organizing. The Civil Rights Movement effectively used nonviolent resistance, legal action, and mass mobilization to challenge racial segregation and discrimination. The Black Lives Matter movement utilizes social media, protests, and legal advocacy to address police brutality and systemic racism.

Cultural production, such as literature, music, and art, plays a crucial role in challenging dominant narratives and promoting alternative perspectives.

Policy Recommendation: Addressing Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

To mitigate racial power imbalances within the criminal justice system, comprehensive police reform is essential. This includes implementing body cameras on all officers, mandatory de-escalation training, and independent investigations of police misconduct. Additionally, addressing implicit bias through training and accountability mechanisms is crucial. These measures, supported by rigorous data collection and analysis to track racial disparities, are essential to fostering a more just and equitable criminal justice system.

The Concept of Racialization

Racialization is a dynamic and ongoing process through which social groups are categorized and ranked based on perceived physical differences, often resulting in the creation and perpetuation of social hierarchies. It is crucial to distinguish racialization from race as a biological construct; while biological differences exist, race as we understand it is a social construct, not a biological reality.

The concept of racialization highlights how these social constructs are created, maintained, and utilized to justify power imbalances and social inequalities.

Defining and Explaining the Process of Racialization

Racialization is the process by which social categories are created and imbued with racial meaning. It is not simply the recognition of physical differences, but the active creation of racial identities and hierarchies through social, political, and economic processes. This involves assigning meaning and value to perceived physical differences, often resulting in the creation of “races” that are then ranked in a hierarchical structure.

These processes are not static; they evolve over time, adapting to changing social and political contexts. Historically, racialization has been instrumental in justifying colonialism, slavery, and other forms of oppression. The role of power structures and institutions is central to this process, as they provide the frameworks and mechanisms through which racial categories are defined, enforced, and maintained.

For instance, legal systems, educational institutions, and media outlets all play a role in shaping and reinforcing racialized understandings of the world.

Examples of Racialization in Different Contexts

The following table provides examples of how racialization manifests across various social contexts. These examples illustrate the diverse mechanisms employed and the profound consequences for racialized groups.

| Context | Example of Racialization | Specific Mechanisms Used | Consequences for the Racialized Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial History | The categorization of indigenous populations in the Americas as “savages” or “uncivilized” to justify colonization and land seizure. | Legal frameworks establishing land ownership and dispossession, military conquest, forced assimilation policies, religious conversion, and the suppression of indigenous languages and cultures. | Genocide, displacement, cultural loss, economic exploitation, and ongoing marginalization. |

| Modern Immigration Policies | The implementation of stricter immigration policies targeting specific ethnic groups perceived as a threat to national security or economic stability. | Stricter visa requirements, increased border security, discriminatory enforcement of immigration laws, and the creation of “undesirable” or “illegal” immigrant categories. | Limited opportunities, social exclusion, economic hardship, and the creation of vulnerable populations subject to exploitation. |

| Media Representation | The stereotypical portrayal of Black men as criminals or thugs in films and television shows. | Overrepresentation of negative stereotypes, underrepresentation of diverse roles and narratives, and the perpetuation of harmful tropes. | Internalized racism, prejudice, limited social mobility, and the reinforcement of negative stereotypes within society. |

| Criminal Justice System | Disproportionate incarceration rates of African Americans and other minority groups. | Racial profiling, biased sentencing, unequal access to legal representation, and the perpetuation of systemic inequalities within the justice system. | Mass incarceration, social stigma, economic hardship, and the disruption of families and communities. |

Consequences of Racialization for Individuals and Communities

Racialization has profound and far-reaching consequences for individuals and communities. These consequences are multifaceted, impacting psychological well-being, socioeconomic status, political participation, and intergenerational relations.

Psychological Impacts

The constant experience of discrimination and prejudice can lead to significant psychological distress, including increased rates of stress, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Internalized racism, where individuals adopt negative stereotypes about their own racial group, is another significant consequence. For example, studies have shown higher rates of depression and anxiety among African Americans subjected to racial microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007).

Socioeconomic Impacts

Racialization contributes significantly to socioeconomic disparities. Racial minority groups often experience lower incomes, wealth accumulation, educational attainment, and access to quality healthcare compared to dominant groups. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau consistently reveals significant wealth gaps between white Americans and racial minorities (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023).

Political Impacts

Racialization can limit political representation and participation. Gerrymandering, voter suppression tactics, and discriminatory practices can effectively disenfranchise racial minority groups, limiting their ability to influence political decision-making. The history of voting rights struggles in the United States provides ample evidence of this (Klarman, 2004).

Intergenerational Trauma

The historical and ongoing experience of racialization can lead to intergenerational trauma, where the effects of racism are transmitted across generations. This can manifest in various ways, including mental health issues, relationship difficulties, and limited social mobility. The lasting effects of slavery and Jim Crow laws on African American communities serve as a powerful example (Alexander, 2010).

Theoretical Perspectives on Racialization

Critical Race Theory (CRT) and intersectionality offer valuable frameworks for understanding racialization. CRT emphasizes the role of race in shaping legal systems and social institutions, highlighting how these systems perpetuate racial inequality. Intersectionality, developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, acknowledges that race intersects with other social categories like gender, class, and sexuality to create unique experiences of oppression and marginalization. Both theories contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of racialization by considering the interplay of various social factors.

Case Study: The Racialization of Japanese Americans During World War II

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II serves as a stark example of racialization. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government, influenced by anti-Japanese sentiment and fear, ordered the relocation of over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry to internment camps. Key actors included government officials, military leaders, and the media, who played a role in constructing a narrative that portrayed Japanese Americans as a threat to national security.

Economic factors, such as the competition for jobs and resources, also contributed to the racialization process. The consequences included the loss of homes, businesses, and livelihoods, as well as lasting psychological trauma and social stigma.

Strategies for Mitigating the Effects of Racialization and Promoting Racial Justice

Addressing the consequences of racialization requires multifaceted strategies. These should include policy reforms aimed at addressing socioeconomic disparities, such as investing in education and healthcare in underserved communities. Promoting diversity and inclusion in media representation is also crucial to counter harmful stereotypes. Furthermore, reforming the criminal justice system to address racial bias in policing, prosecution, and sentencing is essential.

Finally, promoting open dialogue and education about race and racism can help to dismantle prejudice and promote racial justice. These strategies should be grounded in evidence-based research and implemented with the active participation of affected communities.

The Role of Agency and Resistance

Racial formation theory, while acknowledging the powerful structuring effects of race, also highlights the agency of individuals and groups in shaping and resisting racial inequalities. This agency manifests in various forms, from everyday acts of defiance to large-scale social movements. Understanding this resistance is crucial to a complete understanding of racial dynamics and the potential for social change.Individuals and groups employ diverse strategies to challenge racialization and contest racial oppression.

These strategies often involve both individual actions and collective mobilization, reflecting the complex interplay between individual choices and broader social forces. The effectiveness of these strategies varies depending on the context, the power dynamics involved, and the resources available to those resisting.

Forms of Individual Resistance

Individual resistance to racialization can take many subtle yet significant forms. These include acts of everyday defiance such as refusing to internalize negative stereotypes, challenging racist jokes or microaggressions, and actively promoting counter-narratives that celebrate diversity and challenge dominant ideologies. These seemingly small acts can have a cumulative effect, gradually eroding the legitimacy of racist beliefs and practices.

Racial formation theory, a vibrant tapestry woven from social, economic, and political threads, hinges on the interplay of power structures. Understanding these power dynamics often requires analyzing strategic interactions, much like solving complex game theory problems; for a practical approach, check out this resource on how to solve game theory problems with fmincon ib matlab. Returning to racial formation, it’s the dynamic negotiation of these power structures that ultimately shapes racial categories and their meanings over time.

Furthermore, individuals can resist through self-affirmation and the cultivation of a strong sense of self-worth, counteracting the internalized oppression that often accompanies racial marginalization. This internal resistance is critical in building resilience and fostering the capacity for collective action.

Collective Resistance Movements

Collective resistance to racial oppression has historically taken various forms, from boycotts and protests to legal challenges and political organizing. The Civil Rights Movement in the United States provides a powerful example of successful collective resistance. This movement, characterized by a range of strategies including civil disobedience, voter registration drives, and legal battles, significantly challenged racial segregation and discrimination, leading to landmark legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The success of the Civil Rights Movement stemmed from its strategic combination of non-violent protest, legal advocacy, and mass mobilization, effectively challenging the dominant racial order and fostering significant social change.

Strategies of Resistance

The strategies employed by individuals and groups resisting racial domination are diverse and often interwoven. These strategies frequently include: direct action, such as protests, marches, and boycotts; legal challenges, including lawsuits and lobbying for policy changes; political organizing, such as forming coalitions and advocating for legislative reforms; cultural production, such as creating art, literature, and music that challenge dominant narratives; and community building, fostering solidarity and mutual support among marginalized groups.

The specific strategies chosen often depend on the context, the resources available, and the nature of the racial oppression being challenged. For instance, a community facing police brutality might prioritize direct action and legal challenges, while a group seeking to counter negative stereotypes might focus on cultural production and community building. Effective resistance often involves a combination of these approaches, creating a multi-pronged strategy that addresses the problem on multiple levels.

The Role of Intersectionality in Resistance

Recognizing the intersectionality of race with other social categories such as gender, class, and sexuality is crucial to understanding the complexities of resistance. Individuals and groups facing multiple forms of oppression often develop strategies that address these intersecting forms of marginalization. For example, Black feminist movements have challenged both racial and gender inequality, highlighting the unique experiences and struggles of Black women.

This intersectional approach to resistance recognizes the interconnected nature of various forms of oppression and works towards creating more inclusive and equitable social movements.

The Intersection of Race with Other Social Categories

Racial formation theory, while illuminating the construction and impact of race, necessitates a deeper understanding of how race interacts with other social categories to shape lived experiences. Ignoring these intersections leads to an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of social inequality. This section examines the complex interplay of race with class, gender, and sexuality, highlighting the unique challenges faced by individuals at these intersections and the implications for social justice initiatives.

Race Intersecting with Class, Gender, and Sexuality

The lived experiences of individuals are profoundly shaped by the convergence of multiple social categories. Analyzing these intersections reveals disparities not captured by examining race, class, gender, or sexuality in isolation. For instance, Black women experience a unique form of oppression stemming from the combined effects of racism and sexism, facing higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and maternal mortality than both white women and Black men.

Similarly, LGBTQ+ people of color experience compounded marginalization due to homophobia, transphobia, and racism, often facing discrimination in housing, employment, and healthcare. Working-class Asian men, while often perceived as a model minority, may still encounter challenges related to class-based discrimination and the pressure to conform to narrow stereotypes.

| Intersecting Categories | Unique Challenges | Impact on Resource Access & Social Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Black Women | Higher rates of poverty, unemployment, maternal mortality; intersection of racism and sexism leading to unique forms of violence and discrimination. | Limited access to quality healthcare, education, and employment opportunities; reduced social mobility compared to white women and Black men. |

| LGBTQ+ People of Color | Discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and race; higher rates of homelessness, violence, and mental health issues; difficulty accessing affirming healthcare. | Significant barriers to employment, housing, and education; limited social support networks; higher risk of poverty and incarceration. |

| Working-Class Asian Men | Pressure to conform to the “model minority” myth; experience of class-based discrimination despite racial group’s overall higher socioeconomic status; limited access to resources due to class rather than race. | Lower social mobility compared to affluent Asian men; potential for internalized racism and pressure to succeed despite systemic barriers; limited access to mental health services. |

Intersectionality and its Relevance to Racial Formation

Intersectionality, as defined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, is a theoretical framework that examines how various social and political identities combine to create unique modes of discrimination or privilege. Crenshaw’s seminal work highlighted how Black women’s experiences of discrimination are not simply the sum of racism and sexism but a distinct form of oppression that cannot be adequately understood through single-axis frameworks.

Patricia Hill Collins further developed this theory, emphasizing the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, and other social categories in shaping power relations.Intersectionality directly challenges the notion of race as a monolithic category. It reveals the diversity of experiences within racial groups, demonstrating how race intersects with other identities to produce complex and varied forms of marginalization and privilege.

- Intersectionality demonstrates that racial hierarchies are not solely based on race but are also shaped by class, gender, and other social categories.

- It reveals how power structures are interwoven and mutually reinforcing, creating interlocking systems of oppression.

- It highlights the need for analyses that move beyond single-axis frameworks to understand the complexities of social inequality.

- It underscores the importance of coalition building and solidarity across different social groups.

Intersectionality informs contemporary social justice movements by highlighting the need for inclusive and multifaceted approaches to addressing social inequality. Movements advocating for racial justice increasingly recognize the importance of centering the experiences of those at the intersections of multiple marginalized identities.

Multiple Social Categories Shaping Individual Experiences of Race

Social policies often disproportionately impact individuals whose identities are shaped by intersecting social categories. For example, housing discrimination based on both race and class results in the concentration of minority populations in under-resourced neighborhoods, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limited opportunity. Similarly, the criminal justice system disproportionately targets Black and Brown men, reflecting the intersection of race and gender in perpetuating mass incarceration.

Welfare policies, while intended to provide support, may inadvertently create further barriers for individuals facing multiple forms of marginalization.Media representations frequently perpetuate harmful stereotypes related to intersecting identities. For instance, the portrayal of Black women as angry or aggressive, or the hypersexualization of Latina women, reinforces negative stereotypes and limits opportunities for these groups. Conversely, some media representations challenge these stereotypes, offering more nuanced and positive portrayals of individuals at these intersections.

“Growing up as a working-class Black woman in the South, I constantly felt the weight of multiple intersecting identities. The limitations placed upon me by society felt insurmountable, yet the strength and resilience of my community provided me with the tools to navigate those challenges.”

“As a transgender woman of color, I’ve experienced discrimination in every aspect of my life. From being denied housing to facing harassment in the workplace, the intersection of my identities has created a constant struggle for survival and dignity.”

The legacy of slavery and Jim Crow laws in the United States continues to shape current experiences of racial intersectionality. The historical disenfranchisement and economic exploitation of Black Americans have created lasting disparities in wealth, health, and education that disproportionately affect Black women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and working-class communities.

Comparative Analysis: Black Women in the US vs. Working-Class Latinx Men in the US

| Characteristic | Black Women in the US | Working-Class Latinx Men in the US |

|---|---|---|

| Primary forms of marginalization | Racism, sexism, classism | Racism, classism, sometimes xenophobia |

| Experiences in the labor market | Wage gap, occupational segregation, limited advancement opportunities | Low-wage jobs, limited benefits, precarious employment |

| Experiences in the criminal justice system | Over-policing, higher rates of incarceration, harsher sentencing | Over-policing, higher rates of incarceration, potential for deportation |

| Access to healthcare | Limited access to quality healthcare, higher rates of maternal mortality | Limited access to quality healthcare, potential language barriers |

| Similarities | Both groups experience significant economic disadvantage and face systemic barriers to social mobility. Both are disproportionately targeted by law enforcement. | |

| Differences | Black women face unique challenges related to sexism and the intersection of racism and sexism. Working-class Latinx men may face challenges related to xenophobia and language barriers, in addition to racism and classism. |

The Evolution of Racial Formation Theory

Racial formation theory, while solidifying in the mid-1980s with Omi and Winant’s seminal work, is not a theory born in a vacuum. Its development is a product of evolving sociological, anthropological, and historical understandings of race and racism, building upon earlier theoretical frameworks and engaging in ongoing dialogues and critiques. This section traces the evolution of racial formation theory, examining its intellectual precursors, key developments, ongoing debates, and contemporary applications.

Early Influences (Pre-1980s)

The intellectual groundwork for racial formation theory was laid by various scholars across multiple disciplines. Early 20th-century sociological perspectives, such as W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “double consciousness” and the Chicago School’s focus on urban ethnography and social processes, provided crucial insights into the lived experiences of racialized groups and the dynamic nature of racial inequality. Anthropological studies challenging biological notions of race, highlighting the social construction of racial categories, also contributed significantly.

For example, Franz Boas’s critique of racial essentialism paved the way for understanding race as a fluid and culturally contingent concept. Furthermore, historical analyses of slavery, colonialism, and Jim Crow laws exposed the ways in which racial categories were constructed and deployed to maintain systems of power and oppression. These diverse intellectual currents converged to create a fertile ground for the emergence of racial formation theory.

Omi and Winant’s Groundbreaking Work (1986)

Michael Omi and Howard Winant’sRacial Formation in the United States* (1986) is considered the foundational text for racial formation theory. Their central argument is that race is not a fixed or biological reality but a social construct, a product of social relations and historical processes. They introduce the concept of “racial projects,” which they define as “simultaneously an interpretation, representation, or explanation of racial dynamics, and an effort to reorganize and redistribute resources along particular racial lines.” These projects can be found in various social institutions and practices, from legislation and policy to everyday interactions.

Omi and Winant’s work significantly impacted subsequent scholarship by providing a powerful framework for analyzing the dynamic interplay between race as a social structure and race as an individual experience. It shifted the focus from static understandings of race to a dynamic and historically situated perspective.

Post-1986 Developments

Since the publication of

- Racial Formation in the United States*, the theory has undergone significant development and refinement. Scholars have expanded upon the concept of racial projects, exploring their diverse forms and manifestations across different historical periods and social contexts. The role of media, popular culture, and discourse in shaping racial meanings and perceptions has been increasingly emphasized. Furthermore, critiques of the theory have spurred its evolution.

For instance, the integration of intersectionality has led to a more nuanced understanding of how race intersects with other social categories such as gender, class, and sexuality in shaping individual experiences and social structures. Works like Patricia Hill Collins’s

- Black Feminist Thought* (1990) significantly contributed to this intersectional perspective. Debates continue regarding the theory’s applicability to global contexts, prompting adaptations and modifications to account for the diverse ways race is constructed and experienced across different societies.

Contemporary Applications

Racial formation theory continues to be a valuable tool for analyzing contemporary racial dynamics across various fields. In sociology, it is used to examine the persistence of racial inequality in areas such as education, housing, and criminal justice. Political scientists utilize the framework to analyze the role of race in political mobilization, policymaking, and electoral processes. Historians apply it to understand how racial categories have been constructed and deployed throughout history.

For instance, recent research utilizes the framework to analyze the impact of social media on the formation and dissemination of racial ideologies, the rise of new forms of racial activism, and the persistence of systemic racism in contemporary institutions. The theory’s flexibility allows its application to a wide range of contemporary issues, ensuring its continued relevance in understanding race relations.

Key Figures and Their Contributions

| Key Figure | Contribution to Racial Formation Theory | Specific Works/Ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Omi | Co-developed the core tenets of racial formation theory; emphasized the social construction of race; highlighted the role of racial projects in shaping race. | Racial Formation in the United States |

| Howard Winant | Co-developed the core tenets of racial formation theory; emphasized the social construction of race; highlighted the role of racial projects in shaping race. | Racial Formation in the United States |

| Patricia Hill Collins | Integrated intersectionality into racial formation theory, highlighting the interconnectedness of race, gender, and class. | Black Feminist Thought |

| Eduardo Bonilla-Silva | Developed the concept of color-blind racism, analyzing how contemporary racism operates through seemingly race-neutral discourses. | Racism without Racists |

Criticisms of Essentialism

A significant critique of racial formation theory centers on the potential for essentialism – the tendency to reduce complex social phenomena to inherent or fixed characteristics. Some critics argue that while acknowledging the social construction of race, the theory may inadvertently overlook the material realities of racial difference and the lived experiences of racialized individuals. The concern is that focusing solely on the social construction of race might minimize the impact of biological differences, or worse, lead to the denial of the very real consequences of racial discrimination.

This criticism highlights the need for a nuanced approach that recognizes both the socially constructed nature of race and the tangible impacts of racial inequality.

Intersectionality and Racial Formation

The integration of intersectionality has significantly enriched racial formation theory. Intersectionality, a framework developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, emphasizes the interconnectedness of social categories like race, gender, class, and sexuality. It highlights how these categories intersect to create unique experiences of oppression and privilege. Applying intersectionality to racial formation theory reveals how racial projects are not only shaped by race but also by other social categories, and how racial inequality manifests differently for individuals based on their intersecting identities.

This integration has broadened the scope of the theory, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex and multifaceted nature of racial dynamics.

Global Applications

The applicability of racial formation theory to contexts beyond the United States has been a subject of ongoing debate. While the core tenets of the theory – the social construction of race and the role of racial projects – are broadly applicable, the specific forms and manifestations of race and racism vary across different national and global contexts. The historical experiences of racialization, the specific racial categories employed, and the power dynamics at play differ significantly.

Therefore, applying racial formation theory to other contexts requires careful consideration of these contextual factors and potentially modifications to the original framework. This has led to the development of comparative studies that examine the variations in racial formation across different societies.

Future Directions

Future research within racial formation theory will likely focus on several key areas. The increasing role of technology and digital media in shaping racial dynamics will necessitate further investigation into how these technologies contribute to the formation and dissemination of racial ideologies and the construction of racial identities. Further exploration of the relationship between racial formation and other social processes, such as globalization, migration, and environmental change, is also needed.

Additionally, ongoing research will continue to refine the theory’s intersectional approach, examining the complex interplay between race and other social categories in shaping social inequalities. The theory’s continued evolution will depend on engaging with these emerging research questions and critically assessing its strengths and limitations in understanding contemporary racial dynamics.

Applying Racial Formation Theory to Contemporary Issues

Racial formation theory provides a powerful framework for understanding how race is constructed and maintained through social processes, and its application to contemporary issues reveals the ongoing impact of historical and ongoing racial inequalities. By examining social structures, ideologies, and power dynamics, the theory illuminates the persistence of racial disparities across various aspects of social life. This analysis will focus on the ways in which racial formation theory helps to explain mass incarceration, police brutality, and immigration policies in the United States.

Applying racial formation theory requires examining how racial projects – meaning the processes by which social, economic, and political forces create and maintain racial categories and hierarchies – shape contemporary social problems. It’s not simply about individual prejudice, but the systematic ways in which race is embedded in institutions and social structures.

Mass Incarceration and Racial Formation

Mass incarceration in the United States disproportionately affects people of color, particularly Black and Latino individuals. Racial formation theory helps explain this disparity by highlighting the historical legacy of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and ongoing racial bias within the criminal justice system. The “war on drugs,” for example, can be analyzed as a racial project that targeted minority communities, leading to increased arrests, convictions, and sentencing for drug-related offenses, even though drug use rates are not significantly different across racial groups.

The disproportionate policing of minority neighborhoods, harsher sentencing guidelines for certain crimes, and the lack of access to adequate legal representation all contribute to the racial disparities in incarceration rates. This perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage, reinforcing existing racial hierarchies and contributing to ongoing social inequality. The persistent association of certain racial groups with criminality, fostered through media representations and societal biases, reinforces this racial project.

Police Brutality and Racial Formation

Police brutality, particularly against Black individuals, is another critical area where racial formation theory offers valuable insight. The disproportionate use of force by law enforcement against people of color cannot be solely attributed to individual biases of officers. Instead, it reflects the historical and ongoing racialization of policing, where law enforcement agencies have historically been used to control and suppress minority communities.

The militarization of police forces, the prevalence of racial profiling, and the lack of accountability for misconduct all contribute to a system that perpetuates violence against people of color. The ongoing discourse surrounding police brutality reveals the power of racial ideology in shaping public perceptions and policy responses. Furthermore, the lack of significant reform despite widespread protests and awareness highlights the deep-seated nature of racial power dynamics within law enforcement.

Immigration Policies and Racial Formation

Immigration policies in the United States often reflect and reinforce racial hierarchies. The framing of certain immigrant groups as “illegal” or “undesirable” is a racial project that constructs racial boundaries and legitimizes discriminatory practices. The stricter enforcement of immigration laws targeting specific racial or ethnic groups, the construction of borders as sites of racial control, and the ongoing debates surrounding citizenship and belonging all reveal how race plays a central role in shaping immigration policy.

The historical context of immigration policies, which have often been influenced by racist ideologies and fears of racial mixing, continues to shape contemporary immigration debates and practices. The ongoing struggle for immigration reform highlights the enduring power of racial formation in shaping social policy and public opinion.

Case Study: The Application of Racial Formation Theory to Mass Incarceration

A case study focusing on the mass incarceration of African Americans demonstrates the utility of racial formation theory. Examining the historical context, from slavery and convict leasing to the war on drugs, reveals how specific racial projects have shaped the current landscape of incarceration. The disproportionate targeting of African Americans through discriminatory policing practices, harsher sentencing guidelines, and biased judicial processes exemplify how racial formation theory explains the overrepresentation of this group within the prison system.

Analyzing the role of media representations in shaping public perception of crime and criminality, and the ways in which these representations reinforce racial stereotypes, further strengthens the application of this theory. The ongoing debate surrounding criminal justice reform and the need for systemic change highlights the continued relevance of racial formation theory in understanding and addressing this pressing social issue.

Visual Representation of Racial Formation Theory

A visual representation can effectively illuminate the complex interplay of factors within racial formation theory. The following diagram, conceived as a dynamic system, aims to capture the key components and their interrelationships.

The diagram is structured as a central circle representing “Race as a Social Construct,” with several interconnected radiating arrows representing the key processes and influences. The arrows are bidirectional, signifying the constant feedback loops and reciprocal influences within the system. The overall shape is not static; rather, it suggests a constantly shifting landscape reflecting the ever-evolving nature of racial dynamics.

Diagram Description

The central circle, labeled “Race as a Social Construct,” is the core of the diagram. From this central circle, several arrows radiate outwards. One arrow points to “Social Structures” (e.g., legal systems, economic institutions, educational systems), illustrating how these structures both shape and are shaped by racial categories. Another arrow points to “Racial Projects,” encompassing actions and ideologies that create and maintain racial categories (e.g., redlining, affirmative action).

A third arrow leads to “Ideology and Discourse,” showing how dominant narratives and beliefs perpetuate racial inequalities. A fourth arrow represents “Racialization,” the process by which individuals and groups are assigned racial identities and meanings. A fifth arrow connects to “Power Dynamics,” highlighting the uneven distribution of power and resources along racial lines. A sixth arrow points to “Agency and Resistance,” acknowledging the active role individuals and groups play in challenging and resisting racial formations.

Finally, a seventh arrow leads to “Intersectionality,” illustrating how race intersects with other social categories like gender, class, and sexuality to create unique experiences of oppression and privilege. Each arrow’s thickness can vary depending on the historical context or specific situation, illustrating the shifting influence of each component.

The Future of Racial Formation Theory: What Component Creates Racial Formation Theory

Racial formation theory, while providing a powerful framework for understanding the construction and maintenance of racial categories, faces evolving challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. Its continued relevance hinges on its capacity to adapt to the rapidly changing social, technological, and political landscapes. This necessitates a critical examination of its limitations and a proactive exploration of new avenues for research and application.

Evolving Technological Influences on Racial Formation

The proliferation of social media and artificial intelligence presents both challenges and opportunities for racial formation theory. Social media algorithms, for instance, can reinforce existing racial biases through targeted advertising, content filtering, and the amplification of certain narratives. The algorithmic curation of information can create echo chambers, reinforcing pre-existing racial prejudices and limiting exposure to diverse perspectives. Conversely, social media can also serve as a platform for mobilization and resistance, enabling marginalized groups to organize, share experiences, and challenge dominant narratives.

AI systems, trained on biased datasets, can perpetuate and even amplify racial inequalities in areas such as criminal justice, employment, and loan applications. For example, facial recognition technologies have been shown to exhibit higher error rates for individuals with darker skin tones, highlighting the need for critical engagement with these technologies through the lens of racial formation theory.

Globalization and Migration’s Impact on Racial Formation

Globalization and increased migration patterns significantly reshape racial dynamics. The increasing interconnectedness of societies leads to the formation of new hybrid identities and challenges traditional racial categories. Positive impacts include the potential for greater intercultural understanding and the breakdown of rigid racial boundaries. However, globalization can also exacerbate existing inequalities, leading to new forms of racism and xenophobia, as evidenced by the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment in many countries.

The theory must account for the complexities of transnational racial formations and the emergence of new racialized groups and identities that transcend national borders.

Adapting the Theory to Emerging Racial and Ethnic Groups, What component creates racial formation theory

Current racial formation theory needs to adapt to the increasing diversity of racial and ethnic groups and the emergence of hybrid identities. Traditional racial categories often fail to capture the complexities of multiracial identities and the fluidity of racial self-identification. The theory needs to incorporate a more nuanced understanding of how individuals negotiate their racial identities in a globalized world, moving beyond simplistic binary classifications.

This requires a shift towards more fluid and intersectional approaches that acknowledge the complexities of self-identification and lived experiences.

Limitations of Current Racial Formation Theory

While impactful, racial formation theory faces limitations. One key limitation lies in its occasional tendency to overemphasize the role of structural forces while underestimating the agency of individuals and groups in shaping racial dynamics. Furthermore, the theory’s focus on macro-level processes can sometimes overshadow the significance of micro-level interactions and individual experiences. The application of the theory to specific contexts often requires careful consideration of the unique historical, social, and political factors at play.

A more robust theory needs to incorporate a deeper understanding of the interplay between structure and agency, macro and micro processes.

Integrating Intersectionality More Effectively