What are examples of an informal theory in psychology class? This question delves into the fascinating world of everyday understanding versus formally tested psychological concepts. We often rely on intuitive, informal theories to explain behavior, but these “common sense” notions sometimes clash with rigorous scientific findings. This exploration will examine several examples of informal theories frequently encountered in introductory psychology courses, contrasting them with their more formal counterparts and exploring the pedagogical implications of using both approaches in education.

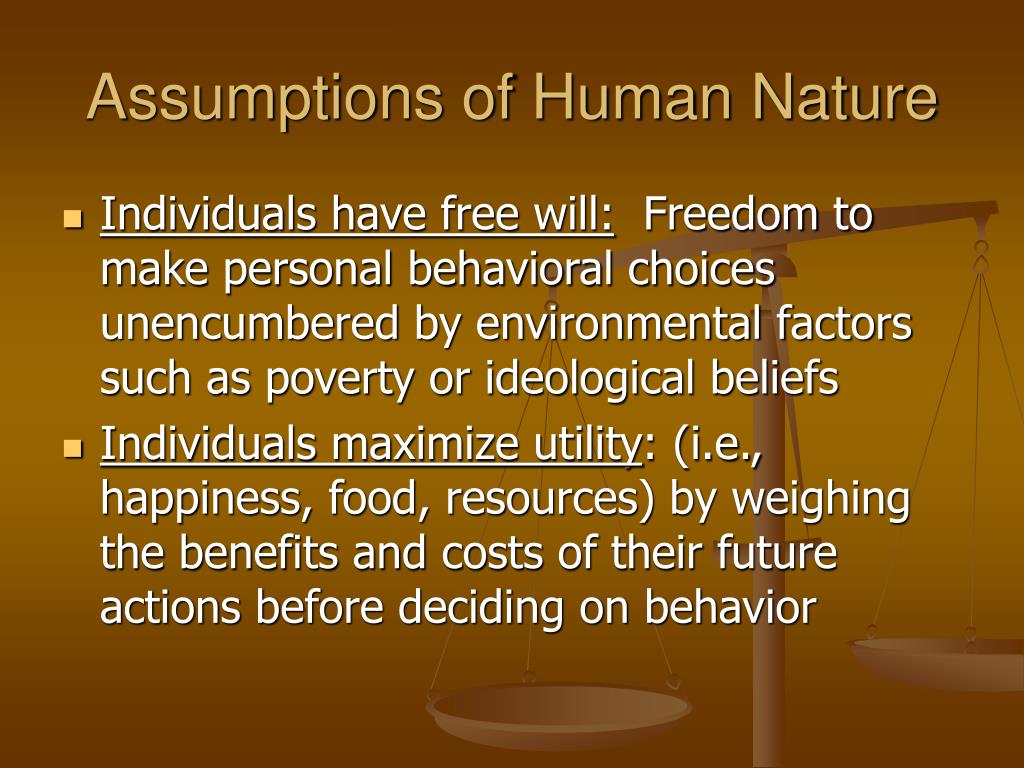

The difference between formal and informal theories lies in their development and validation. Formal theories are rigorously tested using the scientific method, involving hypothesis formation, data collection, and analysis. They are supported by empirical evidence and aim for predictive accuracy. Informal theories, on the other hand, are based on personal experiences, observations, and cultural beliefs. They lack the systematic testing and rigorous validation of formal theories, often leading to oversimplification and biases.

Examples of informal theories include beliefs like “opposites attract” in relationships or “practice makes perfect” in skill acquisition. Understanding the strengths and limitations of both types of theories is crucial for developing a comprehensive understanding of psychology.

Defining Informal Theories in Psychology

Informal theories in psychology represent everyday understandings of human behavior, contrasting with the rigorously tested and empirically supported formal theories. This exploration delves into the distinctions between these two approaches, their limitations, and effective strategies for integrating them in teaching and practice.

Formal Versus Informal Theories: A Comparative Analysis

Formal and informal theories differ significantly in their empirical support, predictive power, and level of abstraction. Formal theories, like Attachment Theory, are based on extensive research, generate testable hypotheses, and offer precise predictions about behavior. In contrast, informal theories, such as the common-sense notion that aggression stems solely from frustration, often lack systematic empirical backing and offer limited predictive capacity.

| Criterion | Formal Theory (e.g., Attachment Theory) | Informal Theory (e.g., “Common Sense” Understanding of Aggression) |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Support | Extensive research, meta-analyses, and replicable findings support its core tenets. | Based on anecdotal observations and personal experiences; lacks systematic empirical validation. |

| Predictive Power | Predicts specific patterns of behavior in relationships based on attachment style. | Offers vague predictions about aggressive behavior, often failing to account for situational factors or individual differences. |

| Level of Abstraction | Clearly defined concepts and constructs, allowing for precise measurement and testing. | Uses broad, loosely defined concepts that are difficult to operationalize and test empirically. |

Examples of Informally Explained Concepts in Introductory Psychology

Introductory psychology often introduces concepts using informal explanations before delving into formal theories. This approach can aid initial comprehension but requires careful transition to rigorous understanding.

| Concept | Informal Explanation | Formal Explanation | Supporting Theory/Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | Memory is like a filing cabinet; we store information and retrieve it when needed. | Memory is a complex cognitive process involving encoding, storage, and retrieval, influenced by factors like attention, emotion, and context. | Multi-store model of memory, levels of processing theory. |

| Motivation | People are motivated by rewards and punishments. | Motivation is a complex interplay of biological, cognitive, and social factors, encompassing intrinsic and extrinsic drives. | Expectancy-value theory, self-determination theory. |

| Personality | Personality is a stable set of traits that determine behavior. | Personality is a dynamic interplay of traits, cognitive processes, and environmental influences, shaped by genetics and experience. | Five-factor model of personality, social cognitive theory. |

| Stress | Stress is simply pressure or anxiety. | Stress is a complex transactional process involving the appraisal of demands and resources, leading to physiological and psychological responses. | Transactional model of stress and coping. |

| Intelligence | Intelligence is a general ability to learn and solve problems. | Intelligence is a multifaceted construct encompassing various cognitive abilities, including fluid and crystallized intelligence. | Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory of intelligence. |

Distinguishing Characteristics of Informal and Formal Theories

Several key characteristics differentiate informal and formal theories. Understanding these differences is crucial for effective teaching and application of psychological principles.

- Empirical Basis: Formal theories are grounded in empirical evidence; informal theories often rely on intuition and anecdotal observations. Example: Formal theories of learning cite experimental research; informal beliefs about learning may be based on personal experiences.

- Testability: Formal theories generate testable hypotheses; informal theories are often difficult to test rigorously. Example: Attachment theory generates testable hypotheses about relationship patterns; the common-sense notion that “opposites attract” is difficult to empirically verify.

- Precision: Formal theories use precise terminology and definitions; informal theories often use vague or ambiguous language. Example: Formal theories define specific types of aggression; informal descriptions of aggression are often broad and imprecise.

- Scope: Formal theories aim for generalizability; informal theories often apply only to specific situations or individuals. Example: Cognitive dissonance theory explains a broad range of behaviors; informal explanations for dissonance may be context-specific.

- Structure: Formal theories are systematically organized; informal theories are often less structured and integrated. Example: Psychoanalytic theory has a well-defined structure; common-sense beliefs about mental health may be fragmented and inconsistent.

Pedagogical Implications of Using Informal Theories in Introductory Psychology

Using informal theories as a starting point in introductory psychology offers benefits and drawbacks. While they can enhance student engagement by connecting to prior knowledge and experiences, they also risk perpetuating misconceptions if not carefully addressed. The pedagogical challenge lies in leveraging students’ existing intuitions to build a foundation for more nuanced formal understanding, fostering critical thinking by encouraging students to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of both formal and informal perspectives.

This approach promotes a deeper understanding of psychological concepts and equips students with the skills to distinguish between credible and unsubstantiated claims.

Informal Theories in Introductory Versus Advanced Courses: A Comparison

The role of informal theories shifts significantly as students progress through their psychology studies. In introductory courses, they serve as a bridge to formal theories; in advanced courses, they become a focus of critical analysis and refinement.

| Aspect | Introductory Psychology | Advanced Psychology |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis | Introducing concepts using informal explanations, building towards formal theories. | Critically evaluating informal theories, identifying limitations, and refining understanding through rigorous research. |

| Approach | Relatively descriptive and less analytical. | Highly analytical and critical, focusing on research methodology and theoretical frameworks. |

| Role | Facilitating initial understanding and engagement. | Serving as a basis for developing more sophisticated and nuanced theories. |

Informal Theories about Human Behavior

Informal theories, unlike formal scientific theories, are everyday explanations we develop to understand ourselves and others. They are often implicit, based on personal experiences and observations rather than rigorous research. These theories significantly shape our interactions and interpretations of the world, even if they are not always accurate or consistent. Understanding these informal theories is crucial to comprehending human behavior and its complexities.

Informal Theories about Personality Traits

Informal theories about personality frequently involve categorizing individuals into simple types. For instance, the common belief that people are either “introverts” or “extroverts” is an example of an informal theory. This oversimplification ignores the nuanced spectrum of personality and the interplay of various traits. Another example is the belief that “opposites attract,” a theory often used to explain romantic relationships, which lacks consistent empirical support.

These informal theories, while offering a seemingly straightforward explanation of personality, often fail to capture the multifaceted nature of human behavior. They may lead to inaccurate judgments and stereotyping of individuals.

Informal Theories about Social Influence

People often rely on informal theories to understand social influence. One common example is the belief that conformity is solely driven by fear of social rejection. While this plays a role, it overlooks other factors like informational social influence (following others because they seem to have more information) and normative social influence (conforming to fit in). Another informal theory concerns persuasion; many believe that repeated exposure to a message automatically increases its persuasiveness, neglecting factors like message quality and audience characteristics.

These simplified understandings can lead to ineffective strategies for influencing behavior and misinterpretations of social dynamics.

Informal Theories concerning Cognitive Processes

Informal theories about cognition often reflect common-sense understandings of how we think and remember. For example, the belief that “practice makes perfect” is a common informal theory regarding learning. While largely true, it oversimplifies the learning process, ignoring factors such as the quality of practice, feedback mechanisms, and individual differences in learning styles. Another example is the belief that memory is like a video recorder; a flawless and accurate representation of past events.

This neglects the reconstructive nature of memory and its susceptibility to biases and distortions. Such informal theories, though intuitively appealing, can lead to unrealistic expectations about learning and memory capabilities.

The Role of Personal Experience in Informal Theories

Personal experiences profoundly shape our understanding of the world, often forming the basis of our informal theories—implicit, untested beliefs about how things work. These theories, while not rigorously scientific, significantly influence our perceptions, decisions, and interactions. This section explores the interplay between personal experience and the development of informal theories, examining both their potential benefits and drawbacks.

Identifying the Influence of Personal Experiences

Personal experiences act as building blocks for informal theories. Specific events and their interpretations contribute directly to the formation of these implicit beliefs. Analyzing these experiences reveals how subjective interpretations shape our understanding.

Specific Examples

- Experience 1: Witnessing a friend’s successful negotiation for a better salary after assertively voicing their needs led to the informal theory that direct communication is key to achieving desired outcomes in professional settings. This theory is rooted in observation and a positive outcome attributed to assertive behavior.

- Experience 2: Experiencing a severe allergic reaction after eating shellfish resulted in a strong informal theory that all seafood is inherently dangerous. This theory is based on a single negative experience and generalizes this fear to all seafood, ignoring the fact that many types of seafood do not cause allergic reactions.

- Experience 3: Consistently observing diligent study habits correlating with high grades among classmates fostered an informal theory that hard work directly translates to academic success. This theory, while generally true, overlooks factors like innate ability and learning styles.

Categorization of Informal Theories

| Experience | Informal Theory | Subject Matter |

|---|---|---|

| Successful salary negotiation observation | Direct communication leads to professional success | Workplace dynamics/social interactions |

| Severe allergic reaction to shellfish | All seafood is dangerous | Personal health/food safety |

| Observing diligent study habits and high grades | Hard work equals academic success | Education/academic performance |

Bias Detection in Informal Theories, What are examples of an informal theory in psychology class

- Experience 1: Confirmation bias might lead to selectively focusing on instances supporting the theory while ignoring cases where assertive communication failed to yield positive results.

- Experience 2: Generalization bias contributes to the overextension of the theory from one negative experience with shellfish to all seafood. The fear response reinforces this bias.

- Experience 3: Availability heuristic might lead to overestimating the importance of hard work while underestimating the role of other factors influencing academic success.

Comparing and Contrasting Influences

The influence of personal experiences on informal theory formation varies significantly depending on the evidence supporting them.

Comparative Analysis

A comparison of experiences 1 and 2 highlights this difference. Experience 1, while not perfectly representative, is supported by some anecdotal evidence and aligns with common sense. Experience 2, however, is heavily influenced by a single negative event and lacks broader supporting evidence. The first theory is more likely to be accurate than the second.

Evidence Evaluation

| Experience | Type of Evidence | Scientific Evidence | Accuracy of Informal Theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful salary negotiation | Anecdotal, observational | Some research supports assertive communication’s effectiveness | Relatively accurate |

| Severe allergic reaction to shellfish | Anecdotal, emotional | Scientific evidence shows allergic reactions are specific | Inaccurate generalization |

Counterfactual Reasoning

Introducing contradictory scientific evidence could significantly alter these informal theories. The shellfish allergy theory would likely be revised to reflect the specificity of allergic reactions. The theory about hard work and academic success would be nuanced to acknowledge other contributing factors. The theory about assertive communication might remain largely unchanged, but its scope could be refined.

Designing a Scenario

Scenario Development

Imagine a person who, after experiencing a car accident on a rainy day, develops a strong belief that driving in the rain is inherently dangerous and statistically much more likely to result in accidents than driving in clear weather. This belief ignores the multitude of factors contributing to accidents.

Scenario Visualization

[A flowchart could be depicted here. It would start with the “Rainy Day Car Accident” box, leading to a “Fear of Driving in Rain” box, then to a “Belief that Rain Causes Accidents” box. Arrows would indicate the causal links. The flowchart would also include a box highlighting the “Neglect of other factors contributing to accidents.”]

Falsification

This inaccurate theory could be falsified by comparing accident statistics for rainy versus clear weather conditions. A research design could involve analyzing large datasets of traffic accident reports to determine the actual relationship between weather conditions and accident rates. This would require controlling for other variables such as traffic volume, road conditions, and driver behavior.

So, you’re wondering about informal theories in psych class? Things like “opposites attract” or “birds of a feather flock together” are prime examples – totally unscientific, yet we all toss ’em around. But to truly understand the accuracy of these “theories,” we need to ask, how many game theories were correct? how many game theories were correct The answer might surprise you, and that’s just as unscientific as believing your best friend is your soulmate because of some cosmic alignment! Back to psych class: maybe “absence makes the heart grow fonder” is another one of those informal gems.

Informal Theories and Everyday Life

Informal theories, while lacking the rigorous testing of formal theories, significantly shape our daily decisions and interactions. They are the ingrained beliefs and assumptions we use to navigate the complexities of life, often unconsciously. Understanding their influence allows us to make more informed choices and improve our decision-making processes.

Examples of Informal Theories Impacting Everyday Decisions

Informal theories profoundly influence our choices. Consider these diverse examples:

- Context: Relationship. Informal Theory: “Birds of a feather flock together.” Decision: Choosing a partner with similar interests and values. Outcome: A generally harmonious and stable relationship due to shared understanding and compatibility. However, this could also lead to a lack of personal growth if the similarities are too restrictive.

- Context: Work. Informal Theory: “Hard work always pays off.” Decision: Accepting a demanding project with long hours, expecting significant career advancement. Outcome: Potential for promotion and recognition if the hard work directly contributes to success; however, it might also lead to burnout or disappointment if the reward doesn’t match the effort.

- Context: Finances. Informal Theory: “A penny saved is a penny earned.” Decision: Prioritizing saving over spending, even when facing tempting purchases. Outcome: Increased financial security and reduced stress related to debt; however, this could limit opportunities for investment or enjoyment.

- Context: Social Situations. Informal Theory: “First impressions are lasting.” Decision: Making a conscious effort to present a positive image during initial encounters. Outcome: Potentially positive initial interactions and relationship building; however, it can also lead to superficial judgments and missed opportunities to connect with people who might be initially perceived negatively.

- Context: Health. Informal Theory: “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” Decision: Incorporating fruits and vegetables into the diet. Outcome: Improved health and well-being due to increased nutrient intake; however, this alone might not be sufficient to prevent all health issues, and an overreliance on this theory could neglect other important health factors.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Relying on Informal Theories

While informal theories offer simplicity and speed in decision-making, they also carry inherent limitations. Benefits:

- Efficiency: They provide quick, readily available “rules of thumb” for navigating everyday situations, avoiding extensive analysis.

- Simplicity: They are easy to understand and apply, requiring minimal cognitive effort.

- Sense of Control: They provide a framework for understanding and predicting events, offering a sense of predictability and control in uncertain situations.

Drawbacks:

- Bias and Inaccuracy: They can be based on limited or biased experiences, leading to inaccurate judgments and flawed decisions (e.g., racial stereotypes impacting hiring decisions).

- Limited Applicability: They might not be applicable in all situations and can fail when confronted with complex or novel circumstances (e.g., relying solely on past experience to solve a new technical problem).

- Resistance to Change: They can be resistant to change and new information, hindering learning and adaptation (e.g., sticking to an outdated investment strategy despite clear market shifts).

Comparison of Formal and Informal Theories in Life Situations

| Life Situation | Formal Theory Applied (if any) | Informal Theory Applied | Outcome/Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choosing a Career | Holland’s Theory of Vocational Personalities | “Follow your passion” | Formal theory offers a structured approach to career selection based on personality and work environment match. Informal theory is simpler but may overlook practical considerations. |

| Managing Finances | Modern Portfolio Theory | “Save for a rainy day” | Formal theory offers a sophisticated approach to investment diversification. Informal theory promotes saving but may miss opportunities for growth. |

| Forming Relationships | Attachment Theory | “Opposites attract” | Formal theory provides insights into attachment styles and relationship dynamics. Informal theory can be overly simplistic and may lead to mismatched relationships. |

| Problem-solving at Work | Systems Thinking | “Trial and error” | Formal theory encourages a holistic approach to problem-solving. Informal theory can be inefficient and potentially wasteful. |

| Navigating Social Situations | Social Exchange Theory | “Be yourself” | Formal theory explains social interactions as a cost-benefit analysis. Informal theory emphasizes authenticity but may not always be socially effective. |

Significance of Informal Theories in Everyday Decision-Making

Informal theories are fundamental to our daily decision-making, providing a quick and intuitive framework for navigating life’s complexities. However, their limitations, including biases and limited applicability, necessitate a balanced approach. A greater understanding of formal theories can enhance our informal ones, leading to more accurate and effective decision-making by providing a framework for testing and refining our intuitive assumptions.

This allows us to identify and mitigate biases, leading to more rational and informed choices.

Sarah, a highly successful businesswoman, consistently relied on her informal theory: “The harder you work, the more successful you’ll be.” This belief fueled her relentless drive and long hours, leading to significant early career success. However, her unwavering dedication eventually led to burnout and strained personal relationships. While her informal theory held true in the initial stages, neglecting her well-being and neglecting other factors in her life resulted in significant negative consequences in the long term. This demonstrates the importance of considering the broader implications of informal theories and the potential need for a more holistic approach to decision-making.

Strategies to Mitigate Negative Consequences of Informal Theories

To improve decision-making, consider these strategies:

- Seek diverse perspectives: Challenge your own assumptions by actively seeking input from others with different backgrounds and experiences.

- Gather information systematically: Before making important decisions, gather relevant data and analyze it objectively, rather than relying solely on intuition.

- Reflect on past decisions: Regularly review past decisions, analyzing what worked well and what could have been improved. This helps identify biases and refine your informal theories.

Key Differences Between Formal and Informal Theories

- Methodology: Formal theories are rigorously tested and validated using systematic methods; informal theories are based on personal experience and observation.

- Validation: Formal theories undergo peer review and empirical testing; informal theories lack rigorous validation.

- Application: Formal theories provide a structured framework for understanding and predicting phenomena; informal theories offer intuitive “rules of thumb” for everyday life.

Informal Theories in Different Psychological Perspectives

Informal theories, those implicit and often unexamined beliefs about human behavior, are shaped and understood differently across various psychological perspectives. Examining these perspectives reveals how our personal understanding of the world influences our interpretations of behavior.

Psychodynamic Perspective on Informal Theories

The psychodynamic perspective emphasizes the role of unconscious processes, defense mechanisms, and early childhood experiences in shaping our understanding of ourselves and others. Informal theories within this framework often reflect unresolved conflicts or ingrained patterns of relating to the world. These theories are rarely articulated explicitly; instead, they manifest in behaviors and interpretations.

- Example 1: The belief that all authority figures are untrustworthy, stemming from a negative early relationship with a parent. This informal theory might lead to rebellious behavior or avoidance of authority. Underlying assumption: Early experiences profoundly and unconsciously shape adult relationships.

- Example 2: The unconscious belief that one is inherently unworthy of love, leading to self-sabotaging behaviors in relationships. Underlying assumption: Unconscious feelings of inadequacy drive interpersonal dynamics.

- Example 3: The belief that expressing emotions openly will lead to rejection, resulting in emotional suppression and withdrawal. Underlying assumption: Emotional vulnerability is perceived as weakness and a threat to safety.

Case Study: A patient consistently chooses partners who are emotionally unavailable, mirroring a pattern of parental neglect experienced in childhood. This reflects an unconscious informal theory that intimacy equals pain, stemming from their early experiences.

Behavioral Perspective on Informal Theories

From a behavioral perspective, informal theories are learned associations between stimuli and responses, shaped by conditioning processes. These theories are reflected in predictable behavioral patterns. Observable behaviors are the primary focus, rather than internal mental states.

- Example 1 (Classical Conditioning): A person develops a fear of dogs (conditioned response) after being bitten by one (unconditioned stimulus). This fear, an informal theory about dogs, guides their avoidance behavior.

- Example 2 (Operant Conditioning): A child believes that whining leads to getting what they want (reinforcement). This informal theory, learned through operant conditioning, maintains the whining behavior.

- Example 3 (Observational Learning): An individual observes others expressing cynicism and negativity, and adopts a similar pessimistic outlook (modeling). This learned negativity becomes an informal theory guiding their interactions and interpretations.

Cognitive Perspective on Informal Theories

The cognitive perspective emphasizes mental processes such as schemas, cognitive biases, and information processing in shaping informal theories. These theories are seen as cognitive structures that guide perception, interpretation, and behavior.

- Example 1: The schema that “all politicians are corrupt” influences how an individual interprets political news and actions, leading to cynicism and disengagement. Underlying assumption: Pre-existing mental frameworks distort information processing.

- Example 2: Confirmation bias leads to seeking out information that confirms pre-existing beliefs (e.g., believing that climate change is a hoax and only reading articles that support that view). This reinforces the informal theory and limits exposure to contradictory evidence.

- Example 3: The use of heuristics (mental shortcuts) can lead to the development of oversimplified and inaccurate informal theories. For example, relying on stereotypes to judge individuals can lead to biased and inaccurate assessments.

Comparison of Informal Theories Across Perspectives

| Perspective | Key Characteristics of Informal Theories | Example Informal Theory 1 | Example Informal Theory 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychodynamic | Unconscious processes, defense mechanisms, early experiences | Belief that intimacy leads to betrayal. | Fear of success rooted in childhood experiences. |

| Behavioral | Learned associations, conditioning, observable behaviors | Avoidance of social situations due to past negative experiences. | Belief that hard work always leads to success. |

| Cognitive | Schemas, cognitive biases, information processing | Stereotypical views about certain groups of people. | Overgeneralizations based on limited experiences. |

Critical Evaluation of Perspectives

The psychodynamic perspective offers rich explanations of the origins of informal theories but can be difficult to test empirically. The behavioral perspective offers strong predictive power for observable behaviors but may oversimplify the complexity of human thought. The cognitive perspective provides a good account of information processing but may neglect emotional and motivational factors.

Additional Illustrative Examples

Psychodynamic: A belief that one is destined to repeat past relationship patterns, reflecting unresolved attachment issues from childhood. Behavioral: A person develops a phobia of public speaking after experiencing negative feedback (punishment) during a presentation. Cognitive: An individual’s belief that they are unlucky, leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy due to negative expectancy bias.

The Limitations of Informal Theories

Informal theories, while providing a framework for understanding the world around us, are inherently limited in their accuracy and predictive power. Their reliance on personal experiences and subjective interpretations makes them prone to biases and inaccuracies, ultimately hindering a comprehensive understanding of human behavior. Understanding these limitations is crucial for developing more robust and scientifically sound explanations.Informal theories often lack the rigorous testing and systematic observation that characterize formal scientific theories.

This lack of empirical support leads to several significant drawbacks.

Inaccuracies and Biases in Informal Theories

The subjective nature of informal theories means they are easily influenced by personal biases, preconceptions, and limited experiences. For example, someone who has had several negative interactions with individuals from a specific cultural group might develop an informal theory that all members of that group share negative characteristics. This is a clear example of generalization and confirmation bias, where only experiences confirming the pre-existing belief are considered, while contradictory evidence is ignored.

Similarly, an individual’s personal worldview, upbringing, and cultural background can significantly shape their informal theories, leading to potentially inaccurate and even harmful conclusions about others. These biases can significantly distort the interpretation of observed behaviors and events.

Dangers of Relying Solely on Informal Theories

Over-reliance on informal theories for understanding behavior can lead to significant misinterpretations and flawed predictions. Because they lack the systematic approach of scientific methods, informal theories cannot reliably predict behavior across different contexts or individuals. For instance, someone might believe that “all shy people are introverted.” This informal theory, while seemingly intuitive, overlooks the diversity within shyness and the possibility of extroverted individuals exhibiting shy behavior in specific situations.

Such oversimplifications can lead to inaccurate judgments and hinder effective communication and interaction. The consequences of relying solely on these theories can range from minor misunderstandings to significant interpersonal conflicts and even discriminatory practices.

Examples of Misconceptions from Informal Theories

Consider the informal theory that “people who are successful are always hardworking.” While hard work is often a component of success, this theory ignores factors like privilege, luck, and inherent talent. This simplification overlooks the complex interplay of various factors contributing to success, leading to a misunderstanding of both the causes and consequences of achievement. Similarly, the belief that “all criminals are inherently bad people” ignores the complex social and environmental factors that can contribute to criminal behavior.

This oversimplified view prevents a nuanced understanding of criminal justice issues and hinders the development of effective crime prevention strategies. These examples demonstrate how informal theories, while seemingly intuitive, can lead to significant misconceptions and a lack of understanding of complex social phenomena.

Informal Theories and Scientific Method

Informal theories, while valuable in everyday life, lack the rigor and objectivity of scientific theories. Bridging this gap requires applying the scientific method to refine and test these intuitive understandings of human behavior. This involves systematically collecting and analyzing data to determine the validity of our informal beliefs.The scientific method provides a structured approach to evaluating informal theories. It begins with observation, leading to the formulation of a testable hypothesis derived from the informal theory.

This hypothesis is then subjected to empirical testing, where data is collected and analyzed to determine if the hypothesis is supported or refuted. The results inform revisions to the informal theory, leading to a more accurate and nuanced understanding.

Testing Informal Theories with Empirical Evidence

Empirical evidence, gathered through systematic observation and experimentation, is crucial for evaluating informal theories. Consider the common informal theory that “people are more likely to help others when they are in a good mood.” To test this, we need to design a study that measures both mood and helping behavior. This could involve manipulating mood (e.g., through exposure to positive stimuli) and then observing subsequent helping behavior in a controlled setting.

Quantitative data, such as the number of times participants help, would then be analyzed to assess the relationship between mood and helping behavior. Statistical analysis would determine the strength and significance of this relationship, offering evidence to either support or challenge the initial informal theory.

A Simple Experiment: Testing the “Bystander Effect”

The bystander effect, a well-established phenomenon in social psychology, states that individuals are less likely to help a victim when other people are present. This is an informal observation often made, but can be rigorously tested. A simple experiment could involve staging a minor emergency (e.g., a staged fall) in a public place. The experiment would manipulate the number of bystanders present (e.g., one bystander, three bystanders, or a crowd) and measure the time it takes for someone to intervene.

The hypothesis derived from the informal theory of the bystander effect would predict that intervention time would increase as the number of bystanders increases. The results, analyzed statistically, would provide empirical evidence to support or refute the informal theory. The data collected would consist of the time elapsed until someone offered assistance, categorized by the number of bystanders present.

A statistically significant increase in intervention time with a higher number of bystanders would support the informal theory of the bystander effect. Conversely, if no significant difference is found, the informal theory would require revision or rejection.

So, you’re wondering about informal theories in psychology class? Things like “people who wear socks with sandals are secretly plotting world domination” or “everyone’s a little bit weird, especially if they need to consult the pagerduty knowledge base at 3 AM.” Yeah, those are the kind of insightful, totally-scientific observations that’ll make you the life of any psych 101 discussion.

Basically, anything that hasn’t been peer-reviewed and is based on questionable evidence qualifies.

The Impact of Culture on Informal Theories

Culture profoundly shapes our understanding of the world, influencing not only our overt behaviors but also the unspoken, implicit theories we hold about human behavior. These informal theories, developed through personal experiences and social interactions, are deeply intertwined with cultural norms, values, and beliefs, leading to significant variations across different societies.Cultural factors influence the development and acceptance of informal theories by providing the context within which we interpret our observations and experiences.

For example, a culture that emphasizes collectivism might foster informal theories that prioritize group harmony and social responsibility, while a culture emphasizing individualism might lead to theories focused on personal achievement and self-reliance. These cultural lenses shape what we notice, how we interpret it, and what conclusions we draw about human actions and motivations.

Cultural Variations in Informal Theories about Human Behavior

Cross-cultural comparisons reveal striking differences in informal theories about various aspects of human behavior. For instance, theories about child development vary widely. In some cultures, independence and self-reliance are emphasized from a young age, leading to informal theories that view early autonomy as crucial for healthy development. Other cultures prioritize interdependence and communal living, fostering informal theories that value cooperation and conformity as essential for a child’s well-being.

Similarly, conceptions of mental health and illness can differ drastically, influencing informal theories about the causes and treatments of psychological distress. In some cultures, mental illness may be attributed to supernatural forces, leading to informal theories that emphasize spiritual healing, while in others, a biomedical model might dominate, fostering informal theories focused on physiological and neurological factors.

Cultural Biases in Informal Theories

The influence of culture on informal theories often leads to biases. Ethnocentrism, the tendency to view one’s own culture as superior and to judge other cultures by its standards, can significantly distort informal theories about human behavior. This can manifest as a tendency to interpret behaviors within other cultures through the lens of one’s own cultural framework, leading to misinterpretations and inaccurate generalizations.

For example, what might be seen as assertiveness in one culture could be interpreted as aggression in another, leading to biased informal theories about personality and social interaction. Furthermore, cultural biases can affect the acceptance and dissemination of informal theories. Theories that align with dominant cultural values are more likely to be accepted and perpetuated, while those that challenge prevailing beliefs might be dismissed or ignored.

This can lead to a perpetuation of cultural stereotypes and misconceptions about human behavior.

Examples of Informal Theories in Developmental Psychology

Informal theories, while lacking the rigor of scientific research, significantly influence our understanding and interactions with individuals across the lifespan. These deeply ingrained beliefs shape our expectations and responses to developmental milestones and challenges in childhood, adolescence, and aging. Understanding these informal theories is crucial for recognizing potential biases and promoting more informed approaches to developmental support.

Examples of Informal Theories in Child Development

The following table presents five common informal theories about child development, outlining their core tenets and providing illustrative scenarios. It’s important to note that these theories are not supported by robust scientific evidence and may lead to inaccurate interpretations of child behavior.

| Theory Name | Core Tenets | Illustrative Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| The “Terrible Twos” | Defiance, emotional outbursts, and testing boundaries are inherent to this age. | A toddler repeatedly throws toys, defying parental requests to stop, interpreted as a typical phase rather than a sign of underlying developmental issues. |

| “Boys will be boys” | Boys are naturally more active, aggressive, and less emotionally expressive than girls. | A boy engages in rough play, and his behavior is excused as “typical boy behavior” rather than addressed as potentially problematic aggression. |

| Early bloomers are more successful | Children who reach developmental milestones early will be more successful in life. | Parents pressure a child who is ahead in reading to continue at an accelerated pace, believing this early advantage will guarantee future academic success, potentially leading to burnout. |

| “Sleep through the night” myth | Infants should sleep through the night from a young age. | Parents become distressed and resort to extreme methods to get their infant to sleep longer stretches, neglecting the child’s developmental needs for frequent feeding and comfort. |

| “Spoiling” a baby | Responding promptly to a baby’s cries will spoil the child. | Parents delay responding to their baby’s cries, believing that consistent attention will create a demanding child, potentially impacting the child’s sense of security and attachment. |

Informal Theories about Adolescence and Parental Practices Across Cultures

Informal theories about adolescent behavior significantly influence parenting styles. Examining three cultural contexts reveals the diverse ways these beliefs shape disciplinary approaches.

Western Individualistic Culture

A prevalent informal theory in Western cultures is that adolescence is a period of inherent rebellion and risk-taking. This often leads to permissive parenting styles, characterized by a focus on individual autonomy and self-discovery, potentially overlooking the need for guidance and structure. Parents might rationalize risky behaviors (e.g., substance experimentation) as a “normal” part of adolescence.

East Asian Collectivistic Culture

In many East Asian cultures, adolescence is viewed as a time of continued dependence on family and adherence to societal expectations. Parenting styles tend to be more authoritarian, emphasizing obedience and academic achievement. Risk-taking behaviors are often seen as reflecting negatively on the family, leading to strict discipline and monitoring.

Indigenous Culture (Example: Māori Culture in New Zealand)

Within Māori culture, adolescence is viewed within a holistic framework, emphasizing the importance of whānau (family) and community. Parenting approaches integrate traditional values and practices, focusing on mentorship, cultural transmission, and the development of strong social connections. While risk-taking might still be a concern, the response often prioritizes restorative justice and community support rather than solely punitive measures.

Informal Theories Regarding Aging and Cognitive Decline and Healthcare Decisions

Informal theories about aging significantly impact healthcare decisions.

Theory 1: “Memory Loss is Inevitable”

This theory suggests that memory decline is a natural and unavoidable part of aging. A real-world example is an older adult experiencing memory lapses but delaying medical attention, attributing it to age rather than a potentially treatable condition like early-stage dementia. Positive consequences might be a reduced fear of aging, while negative consequences could include delayed diagnosis and treatment of serious conditions.

Theory 2: “Older Adults are Frail and Dependent”

This theory leads to assumptions about physical and cognitive limitations, often resulting in decreased opportunities for social engagement and independent living. An example is the reluctance to encourage physical activity or cognitive stimulation among older adults, limiting their quality of life. Positive consequences are minimal; negative consequences include increased risk of social isolation, depression, and accelerated decline.

Theory 3: “Medication Side Effects are Normal in Old Age”

This theory may lead to underreporting of side effects or non-adherence to medication regimens. An example is an older adult experiencing dizziness from a medication but assuming it’s a normal consequence of aging, rather than reporting it to their doctor. This can have severe negative consequences, including falls and other health complications.

Comparison of Informal Theories Across Developmental Stages

The following table compares two informal theories across childhood, adolescence, and aging.

| Theory | Childhood | Adolescence | Aging | Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Inherent Traits” | “Difficult child” (innately challenging temperament) | “Rebellious teenager” (naturally defiant) | “Grumpy old person” (inherently irritable) | Assumes fixed personality traits; minimizes environmental influence | Specific behavioral manifestations vary by stage |

| “Decline is Inevitable” | “Slow learner” (inherent cognitive limitations) | “Unmotivated adolescent” (lack of inherent drive) | “Cognitive decline” (inevitable memory loss) | Focuses on limitations; neglects potential for growth or intervention | Severity and manifestation of decline vary by stage; implications for intervention differ |

Informal Theories and Clinical Practice

Informal theories, the implicit and often unconscious beliefs about human behavior that clinicians hold, significantly shape their approach to patients. These ingrained perspectives, developed through personal experiences and observations, can influence everything from diagnosis and treatment selection to the therapeutic relationship itself. Understanding the potential impact of these informal theories is crucial for ethical and effective clinical practice.Informal theories might influence a clinician’s approach to a patient in numerous ways.

For example, a clinician who believes that all depression stems from childhood trauma might focus solely on exploring a patient’s past, neglecting other potential contributing factors such as current life stressors or biological predispositions. Conversely, a clinician holding a strong belief in the power of positive thinking might overlook the debilitating effects of severe depression, potentially leading to inadequate treatment.

These biases, even when unintentional, can profoundly affect the patient’s experience and outcome.

Ethical Implications of Relying on Informal Theories in Clinical Settings

Relying heavily on informal theories in clinical settings raises several ethical concerns. The most significant is the potential for biased diagnoses and treatments. A clinician’s personal biases can lead to misinterpretations of patient behavior and symptoms, resulting in inaccurate diagnoses and inappropriate treatment plans. This can cause harm to the patient, delaying effective treatment and potentially exacerbating their condition.

Furthermore, the lack of transparency surrounding informal theories can undermine the therapeutic relationship, eroding trust between clinician and patient. A patient deserves to know the rationale behind their treatment, and reliance on unacknowledged personal biases prevents this open communication. Failing to ground interventions in evidence-based practices and instead relying on personal beliefs also constitutes a breach of professional responsibility.

Avoiding Sole Reliance on Informal Theories in Therapeutic Interventions

To mitigate the risks associated with informal theories, clinicians must actively engage in self-reflection and continuous professional development. Regular supervision, where a clinician discusses their cases with a more experienced colleague, provides a crucial opportunity to identify and address potential biases. Critically evaluating one’s own assumptions and beliefs about human behavior is also essential. This involves actively seeking out diverse perspectives and engaging with the scientific literature to stay abreast of current research and evidence-based practices.

Clinicians should strive to base their interventions on empirical evidence, using validated assessment tools and treatment approaches whenever possible. Documenting the rationale behind clinical decisions, including the consideration of both evidence-based practices and individual patient characteristics, ensures transparency and accountability. Finally, actively seeking feedback from patients regarding their experience in therapy helps to identify areas where personal biases might be influencing the therapeutic process.

By employing these strategies, clinicians can minimize the influence of informal theories and provide more effective and ethical care.

The Evolution of Informal Theories: What Are Examples Of An Informal Theory In Psychology Class

Informal theories, the everyday explanations we construct to understand the world around us, are not static entities. They are dynamic, constantly evolving in response to new information, experiences, and social influences. Understanding this evolutionary process is crucial for appreciating both the strengths and limitations of informal theories in shaping our beliefs and behaviors.

Temporal Dynamics of Informal Theory Evolution

Informal theories evolve across various timescales, from rapid shifts in response to immediate experiences to gradual transformations over decades. The rate and nature of these changes are influenced by a multitude of factors, including the individual’s cognitive style, social environment, and the type of information encountered.

- Short-term evolution: Imagine a person who believes all dogs are friendly. After a negative encounter with an aggressive dog, their theory might immediately shift to include a caveat about breed or specific circumstances. This is a rapid adjustment based on a single, impactful experience. Timeline: Before encounter – belief in friendly dogs; After encounter – belief modified to include exceptions.

- Mid-term evolution: Consider a student initially believing that studying hard guarantees high grades. Over a semester, they may encounter evidence contradicting this, such as high-achieving peers who appear to study less. This might lead to a nuanced theory acknowledging factors like study strategies and innate ability. Timeline: Beginning of semester – belief in direct correlation between study time and grades; Mid-semester – belief modified to include other factors; End of semester – refined understanding of multiple contributing factors.

- Long-term evolution: A person’s theory about romantic relationships might evolve significantly over their lifetime. Early beliefs, perhaps based on idealized portrayals in media, might be gradually revised through personal experiences, observations of others’ relationships, and exposure to diverse perspectives. Timeline: Adolescence – idealized view of relationships; Young Adulthood – experiences leading to a more realistic understanding; Maturity – complex, nuanced view shaped by diverse experiences and reflections.

Mechanisms Driving Changes in Informal Theories

Several cognitive and social mechanisms drive the evolution of informal theories. Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias (favoring information confirming existing beliefs) and the availability heuristic (overestimating the likelihood of easily recalled events), can significantly influence how we process new information and adjust our theories. Social influence, including peer pressure and exposure to media narratives, also plays a crucial role in shaping and modifying our informal theories.

The availability and accessibility of information, particularly in the digital age, further contribute to this dynamic process. For instance, access to diverse viewpoints online can lead to faster and more significant changes in informal theories compared to situations with limited information sources.

Case Study Analysis: The Evolution of Beliefs about the Efficacy of Vitamins

The belief in the widespread efficacy of vitamin supplements for disease prevention and health improvement has undergone significant changes over the past two decades.

| Year | Description of Theory | Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Early 2000s | Widespread belief in the significant health benefits of taking multivitamins, even for healthy individuals. | Marketing campaigns emphasizing the importance of supplementation, limited critical evaluation of research findings. |

| Mid-2010s | Increased skepticism regarding the benefits of multivitamins for healthy individuals; focus shifts towards specific deficiencies. | Publication of large-scale studies showing limited or no benefit of multivitamins for healthy populations; increased media scrutiny of supplement industry. |

| Present | More nuanced understanding; recognition of potential benefits for specific groups (e.g., pregnant women, individuals with deficiencies) and the potential risks of excessive intake. | Growing body of research focusing on specific vitamins and their roles in health; improved understanding of nutrient absorption and interactions. |

Cognitive Biases Contributing to Persistence of Inaccurate Theories

Cognitive biases play a significant role in maintaining inaccurate informal theories, even in the face of contradictory evidence.

- Confirmation bias: People tend to seek out and interpret information that confirms their existing beliefs, while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. For example, someone who believes vaccines cause autism might selectively focus on anecdotal evidence supporting this claim, while dismissing large-scale studies demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.

- Availability heuristic: People tend to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easily recalled, often due to their vividness or recent occurrence. For instance, the fear of flying might be disproportionately high due to the media’s tendency to highlight plane crashes, even though flying is statistically safer than driving.

- Anchoring bias: People tend to rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive (the “anchor”) when making judgments, even if that information is irrelevant or inaccurate. For example, an initial high price for a product can anchor a consumer’s perception of value, making them less likely to negotiate or consider cheaper alternatives.

Social and Cultural Factors Perpetuating Inaccurate Theories

Social networks, cultural norms, and media influence all contribute to the persistence of inaccurate informal theories. Social groups often reinforce existing beliefs through shared narratives and discussions, creating echo chambers where dissenting opinions are marginalized. Cultural norms and traditions can also perpetuate misconceptions, particularly in areas such as health and medicine. Media, with its focus on sensationalism and simplified narratives, can inadvertently spread inaccurate information, contributing to the widespread acceptance of flawed beliefs.

For example, the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 on social media highlights the powerful role of social and cultural factors in perpetuating inaccurate theories.

Motivated Reasoning and Resistance to Change

Motivated reasoning refers to the tendency to process information in a way that supports pre-existing beliefs and values, even if that means distorting or ignoring evidence to the contrary. This can lead to significant resistance to changing inaccurate beliefs, even when confronted with overwhelming contradictory evidence. For example, climate change denial often involves motivated reasoning, where individuals selectively interpret or dismiss scientific evidence that contradicts their worldview or vested interests.

Criteria for Evaluating the Validity of Informal Theories

A systematic approach is necessary to differentiate well-supported informal theories from misconceptions.

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Empirical Evidence | Is there evidence from observation or experimentation to support the theory? |

| Logical Consistency | Is the theory internally consistent, free of contradictions? |

| Power | Does the theory effectively explain the phenomenon it addresses? |

| Falsifiability | Can the theory be disproven through observation or experimentation? |

| Parsimony | Does the theory offer the simplest explanation consistent with the evidence? |

Comparative Analysis of Informal Theories

Let’s compare two informal theories:

| Criterion | Well-Supported Theory: Germ Theory of Disease | Misconception: “The common cold is caused by being cold.” |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Evidence | Abundant experimental and observational evidence linking specific microorganisms to various diseases. | Anecdotal evidence; lack of scientific support. |

| Logical Consistency | Consistent with broader biological understanding of disease transmission. | Logically inconsistent; exposure to cold temperatures does not directly cause viral infections. |

| Power | Effectively explains the spread and prevention of infectious diseases. | Fails to explain the underlying mechanism of cold infections. |

| Falsifiability | Can be (and has been) tested and refined through experimentation. | Difficult to falsify due to the lack of a testable mechanism. |

| Parsimony | Provides a relatively simple explanation for a complex phenomenon. | A less parsimonious explanation compared to the germ theory. |

Addressing the Misconception: “The common cold is caused by being cold.”

Correcting this misconception requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Provide accurate information: Explain the role of viruses in causing colds and the lack of a causal link between cold temperatures and viral infections.

- Address cognitive biases: Acknowledge and counter the availability heuristic (e.g., people remember getting sick after being cold) by emphasizing the lack of causal relationship.

- Use clear and relatable language: Avoid technical jargon and use simple, understandable examples to illustrate the concept.

- Promote critical thinking: Encourage individuals to question their assumptions and evaluate evidence critically before accepting beliefs.

- Leverage social influence: Use credible sources and trusted figures to communicate the accurate information.

Bridging the Gap

Informal theories, while valuable in everyday life and offering initial insights, lack the rigor needed for scientific understanding. Transforming these intuitive understandings into testable hypotheses and robust formal theories requires a structured approach, bridging the gap between personal observation and empirical validation. This process involves careful definition, operationalization, and systematic investigation.Transforming an Informal Theory into a Testable Hypothesis involves several key steps.

First, the informal theory must be clearly articulated and defined. Vague notions need to be refined into specific, measurable statements. For example, an informal theory like “people are more helpful when they are in a good mood” needs to be operationalized. What constitutes “helpfulness”? What defines a “good mood”?

These aspects must be precisely defined using measurable variables. Next, this refined statement is translated into a testable hypothesis, a specific prediction about the relationship between the defined variables. For instance, the hypothesis could be: “Individuals experiencing positive affect (measured by self-reported mood scales) will exhibit significantly greater helping behavior (measured by time spent assisting a confederate) than individuals experiencing neutral affect.” This hypothesis is now ready for empirical testing.

Designing a Research Study to Investigate an Informal Theory

A well-designed research study is crucial for testing a hypothesis derived from an informal theory. Consider the example above. A suitable research design would be an experimental study, manipulating the independent variable (mood) and measuring the dependent variable (helping behavior). Participants could be randomly assigned to either a positive mood induction condition (e.g., watching a funny video) or a neutral mood condition (e.g., watching a neutral documentary).

The helping behavior could be assessed through observation or self-report measures. Control groups and standardized procedures are essential to minimize bias and ensure the validity of the findings. Data analysis would involve statistical tests to determine if there is a significant difference in helping behavior between the two mood conditions. This process would allow researchers to assess the validity of the initial informal theory.

Developing a Formal Theory Based on Empirical Evidence

Once a hypothesis derived from an informal theory is tested, the results inform the development of a more formal theory. If the experimental results support the hypothesis (e.g., participants in the positive mood condition showed significantly more helping behavior), this provides evidence to support the initial informal theory, albeit in a more refined and precise form. However, a single study is rarely sufficient to establish a robust formal theory.

Multiple studies, using different methodologies and populations, are necessary to replicate and extend the findings. This process of accumulating empirical evidence allows for the refinement and modification of the initial informal theory, leading to the development of a more comprehensive and nuanced formal theory. For instance, the initial theory about mood and helping behavior might be expanded to include other factors influencing helping behavior, such as social norms or perceived cost-benefit ratios, creating a more complete theoretical model.

This iterative process of hypothesis testing, data analysis, and theoretical refinement is central to the scientific method in psychology.

General Inquiries

What is the difference between a hypothesis and an informal theory?

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction derived from a theory (formal or informal). An informal theory is a broader, untested explanation based on observation or belief, while a hypothesis is a more focused, falsifiable statement.

Can informal theories ever be accurate?

Yes, sometimes informal theories align with formal findings. However, their accuracy is not guaranteed and depends on the available evidence and the absence of biases. Formal testing is needed for confirmation.

How can I avoid relying too heavily on informal theories in my own life?

Cultivate critical thinking skills, seek out diverse perspectives, and actively look for empirical evidence before making decisions based on beliefs. Question your assumptions and consider alternative explanations.