What are examples of an informal theory in psychology? Ever wondered why you believe certain things about human behavior, even without formal training? We all develop informal theories—gut feelings about how people think, feel, and act. These aren’t based on rigorous research, but on personal experiences, observations, and biases. This thread dives into the fascinating world of these everyday psychological theories, exploring their strengths, weaknesses, and how they differ from their more formal counterparts.

From noticing patterns in friendships (social psychology) to believing you learn best by repetition (cognitive psychology), we build these mental models to navigate the complexities of life. But how accurate are they? We’ll examine the potential pitfalls of relying solely on informal theories, like confirmation bias and limited generalizability, and discuss how they might be formalized into testable hypotheses through rigorous research.

We’ll also explore how these informal beliefs impact professional practice and everyday decision-making.

Defining Informal Theories in Psychology

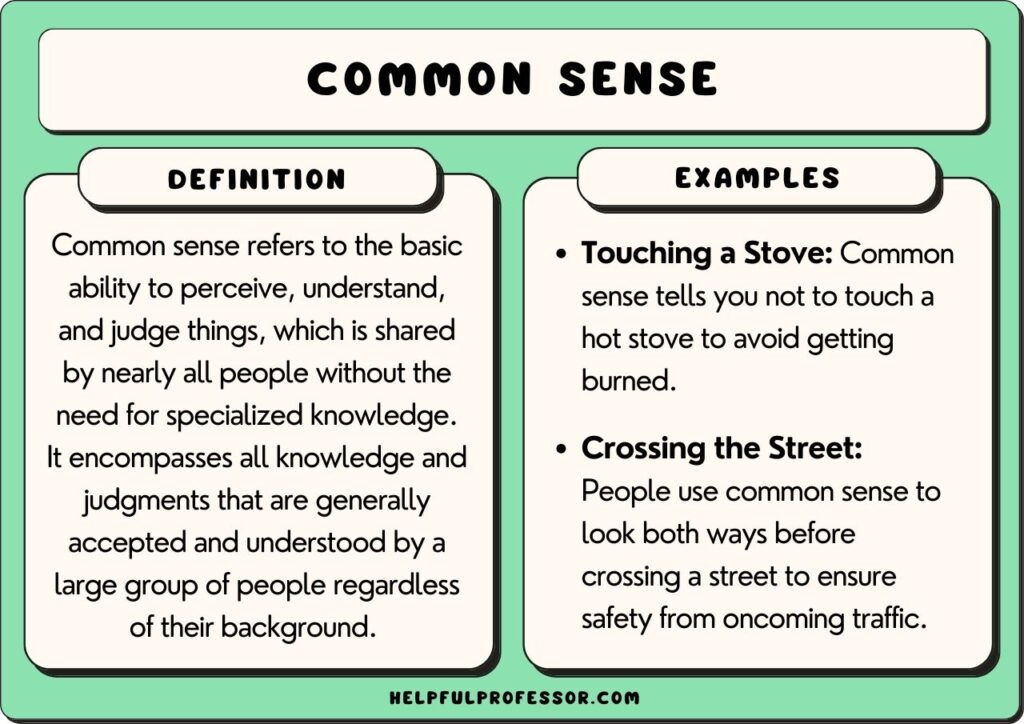

Informal theories in psychology represent our everyday understandings of human behavior, shaped by personal experiences and observations. They differ significantly from formal, scientific theories in their development, testing, and application. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the limitations and potential of both approaches.

Characteristics of Informal and Formal Theories

The following table contrasts the key characteristics of informal and formal theories in psychology:

| Characteristic | Informal Theory | Formal Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Method of Formation | Intuitive; based on personal experiences and observations | Systematic; based on research, data analysis, and rigorous testing |

| Level of Empirical Support | Anecdotal; relies on personal examples and subjective interpretations | Data-driven; supported by empirical evidence from controlled studies |

| Predictive Power | Specific; predicts behavior in limited contexts | Generalizable; predicts behavior across various contexts and populations |

| Role of Biases | Significant presence of various biases (confirmation, availability, etc.) | Attempts to minimize biases through rigorous methodology and controls |

Examples of Everyday Observations Leading to Informal Theories

Everyday observations frequently lead to the development of informal theories. Here are three examples:

- Social Psychology: Observation: People tend to be more helpful when they are in a good mood. Informal Theory: A positive mood increases prosocial behavior. Potential Biases: Confirmation bias (only noticing instances supporting the theory) and availability heuristic (overestimating the frequency of helpful behavior in positive moods due to salience).

- Developmental Psychology: Observation: Children who are read to frequently develop larger vocabularies. Informal Theory: Early exposure to reading enhances language development. Potential Biases: Correlation-causation fallacy (assuming reading directly causes vocabulary growth, ignoring other contributing factors like socioeconomic status) and sampling bias (observations limited to a specific group of children).

- Cognitive Psychology: Observation: Multitasking reduces the efficiency of completing tasks. Informal Theory: The human brain is not well-suited for simultaneous processing of multiple complex tasks. Potential Biases: Oversimplification (ignoring the possibility that task complexity and individual differences affect multitasking performance) and hindsight bias (believing the theory to be obvious after observing its effects).

Limitations of Relying Solely on Informal Theories

Relying solely on informal theories can lead to inaccurate and misleading conclusions about psychological phenomena. Here are four key limitations:

- Confirmation Bias: We tend to seek out and interpret information that confirms our existing beliefs, ignoring contradictory evidence. Example: Believing that all introverts are shy and ignoring instances of outgoing introverts.

- Lack of Falsifiability: Informal theories are often difficult to disprove, making it impossible to refine or improve them. Example: The claim “people act strangely around full moons” is difficult to disprove due to its vagueness and lack of specific predictions.

- Limited Generalizability: Informal theories are based on limited observations and may not apply to broader populations or contexts. Example: Concluding that all members of a specific nationality are dishonest based on a few negative encounters.

- Susceptibility to Inaccurate Interpretations: Informal theories can be influenced by cognitive biases and lack of systematic data collection, leading to flawed conclusions. Example: Attributing a child’s poor performance in school solely to laziness, ignoring potential learning disabilities or stressful home environments.

Informal Theories in Everyday Life vs. Professional Practice

Informal theories are constantly used in everyday life to understand and predict behavior. While helpful for navigating social situations and making quick judgments, they can also lead to inaccurate assumptions and prejudice. In contrast, professional psychological practice demands a rigorous approach, relying on formal theories supported by empirical evidence. For instance, an informal theory might suggest that a person’s anger stems from inherent personality flaws, whereas a professional psychologist would utilize established theories and data-driven assessments to identify potential underlying causes, such as trauma or mental health conditions.

The use of informal theories in everyday life can be helpful for quick decision-making and navigating social interactions, but they lack the rigor and objectivity needed for reliable diagnosis and treatment in a professional setting.

Informal Theories in Social Psychology

Informal theories in social psychology are the everyday, often unspoken, beliefs we hold about how people interact and behave in groups. Unlike formal, rigorously tested theories, these are intuitive understandings shaped by personal experiences, observations, and cultural norms. They significantly influence our social interactions, sometimes leading to accurate predictions, and other times resulting in biases and misunderstandings. Understanding these informal theories is crucial to navigating the complexities of social life and improving our interpersonal relationships.

These everyday understandings of social dynamics profoundly shape our perceptions and behaviors within groups and influence how we interpret others’ actions. They often operate unconsciously, guiding our judgments and decisions without conscious awareness. This section will explore some common examples of these informal theories, their impact on relationships, and how they differ from established social psychology models.

Examples of Informal Theories Regarding Group Dynamics and Social Influence

Informal theories about group dynamics often center around stereotypes and generalizations about group behavior. For instance, a common informal theory suggests that “birds of a feather flock together,” implying that people tend to associate with others who share similar characteristics. Another prevalent belief is that “opposites attract,” suggesting that individuals are drawn to those with contrasting personalities. These beliefs, while sometimes accurate, are oversimplifications and can lead to biased judgments and inaccurate predictions.

Consider the informal theory that “groupthink” always leads to poor decisions; this is a simplification of a complex phenomenon. While groupthink, the tendency for groups to prioritize consensus over critical evaluation, can indeed lead to flawed outcomes, it’s not an inevitable consequence of group decision-making. Effective group processes can mitigate the negative effects of groupthink.

The Impact of Informal Theories on Interpersonal Relationships

Informal theories significantly shape our interpersonal relationships. For example, the belief that “actions speak louder than words” can lead us to prioritize observed behavior over verbal declarations of affection or commitment. This can create conflict if actions don’t align with stated intentions. Similarly, the informal theory that “absence makes the heart grow fonder” might lead individuals to believe that distancing themselves from a partner will strengthen the bond, potentially leading to unintended negative consequences.

The informal theory that “familiarity breeds contempt” suggests that close relationships inevitably degrade over time; this is a pessimistic view that doesn’t account for the effort and work required to maintain healthy relationships. The impact of these informal theories can range from minor misunderstandings to significant relationship problems, depending on the accuracy of the belief and the context in which it is applied.

Comparison of Informal Theories with Established Social Psychology Models

Established social psychology models, such as Social Identity Theory and the Elaboration Likelihood Model, offer more nuanced and empirically supported explanations of social phenomena than informal theories. Social Identity Theory, for example, explains how individuals derive part of their self-concept from their group memberships, providing a more robust framework for understanding intergroup relations than the simple “birds of a feather” informal theory.

Similarly, the Elaboration Likelihood Model provides a detailed account of persuasion, moving beyond the simple informal belief that repetition leads to acceptance. Formal models are grounded in research, using rigorous methods to test hypotheses and refine understanding. In contrast, informal theories are often based on anecdotal evidence and personal experiences, making them less reliable and potentially biased. However, it’s important to note that informal theories often serve as the basis for initial hypotheses that are later tested through formal research.

The interplay between informal observations and formal models is a dynamic and crucial aspect of the advancement of social psychology.

Informal Theories in Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive psychology explores the inner workings of our minds, focusing on mental processes like memory, attention, and problem-solving. While formal theories in this field are rigorously tested and refined through scientific research, we all possess our own informal theories – intuitive beliefs about how our minds work, shaped by personal experiences and observations. These informal theories, while not scientifically validated, profoundly influence our behavior and understanding of the world.

Understanding these informal theories is crucial for both self-awareness and for designing effective interventions in fields like education and therapy.

Identifying Common Informal Theories

Informal theories about cognitive processes are deeply ingrained in our everyday thinking. They represent our personal, often implicit, models of how memory, attention, and problem-solving function. Recognizing these theories allows us to critically evaluate their accuracy and potential biases.

Memory

People often develop intuitive beliefs about their memory capabilities. These beliefs, while sometimes accurate, can also be influenced by biases and lack scientific grounding.

| Informal Theory | Memory Type | Example |

|---|---|---|

| “I have a good memory for faces.” | Episodic and Visual Memory | Someone easily recalls faces of people they’ve met before, even after years, but struggles to remember names. |

| “I remember things better when I write them down.” | Semantic and Episodic Memory | A student finds that writing notes during a lecture helps them retain information better than simply listening. |

| “I learn best through repetition.” | Procedural and Semantic Memory | A musician practices a piece repeatedly to improve their performance. The repeated action strengthens procedural memory, while repeated exposure to musical theory reinforces semantic memory. |

Attention

Our informal theories about attention significantly shape how we approach tasks and manage our time. These theories often reflect our individual strengths and weaknesses in focusing our cognitive resources.

The following are common informal theories related to attention, categorized by attention type:

- “Multitasking is efficient.” This theory relates to divided attention. Many believe they can effectively handle multiple tasks simultaneously, but research suggests this often leads to reduced performance on each task.

- “I can’t focus when there’s noise.” This relates to selective attention. Noise acts as a distractor, making it difficult to filter out irrelevant stimuli and focus on the task at hand.

- “I need breaks to maintain concentration.” This theory relates to sustained attention. Regular breaks are often necessary to avoid cognitive fatigue and maintain focus over extended periods.

Problem-Solving

Our approaches to problem-solving are guided by our intuitive beliefs about what strategies work best for us. These beliefs can be helpful, but they can also lead us down unproductive paths.

Here are examples of informal theories about problem-solving:

- “I work best under pressure.” This theory suggests a preference for working under time constraints, which might involve a trial-and-error approach or relying on intuition.

- “Breaking down a problem into smaller parts helps.” This reflects a means-ends analysis strategy, where complex problems are decomposed into manageable sub-problems.

- “I rely on intuition to solve problems.” This approach uses heuristics and gut feelings rather than a systematic, analytical process.

The Influence of Biases

Cognitive biases significantly shape the development and maintenance of our informal theories. These biases can lead to inaccurate or incomplete understandings of our cognitive processes.

Bias Identification and Illustrative Examples, What are examples of an informal theory in psychology

The following table illustrates how cognitive biases might influence the informal theories discussed earlier. Each bias-theory pairing includes two concrete examples demonstrating the bias’s influence.

| Informal Theory | Cognitive Bias | Illustrative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| “I have a good memory for faces.” | Confirmation Bias |

|

| “I remember things better when I write them down.” | Availability Heuristic |

|

| “I learn best through repetition.” | Anchoring Bias |

|

| “Multitasking is efficient.” | Overconfidence Bias |

|

| “I can’t focus when there’s noise.” | Availability Heuristic |

|

| “I need breaks to maintain concentration.” | Confirmation Bias |

|

| “I work best under pressure.” | Confirmation Bias |

|

| “Breaking down a problem into smaller parts helps.” | Illusory Correlation |

|

| “I rely on intuition to solve problems.” | Overconfidence Bias |

|

Informal Theories in Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology explores the intricate journey of human growth, from infancy to adulthood. Understanding this journey is crucial, and parents, naturally, develop their own informal theories – often unspoken beliefs – about how their children develop. These theories, shaped by personal experiences, cultural norms, and media portrayals, profoundly influence parenting styles and, consequently, a child’s development. This section delves into the specifics of these informal theories in the context of cognitive, socio-emotional, and physical development.

Examples of Informal Theories in Developmental Psychology

Parents’ informal theories are powerful, shaping their interactions with their children. Understanding these beliefs allows for a more nuanced appreciation of parenting practices and their impact.

Examples of Informal Theories Regarding Cognitive Development

The following table presents five distinct examples of informal theories parents hold regarding their child’s cognitive development, categorized by age range, description, and potential origin.

| Informal Theory | Age Range | Description | Potential Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early exposure to multiple languages enhances cognitive abilities. | 0-3 years | Belief that bilingual or multilingual environments stimulate brain development and improve cognitive flexibility. | Research findings, personal observation of multilingual individuals. |

| Children learn best through hands-on activities. | 2-5 years | Emphasis on experiential learning and play-based activities for cognitive development. | Personal experience, educational philosophies. |

| Formal schooling is crucial for intellectual development. | 5-7 years | Belief that structured academic learning in a school setting is essential for cognitive growth. | Cultural norms, societal expectations. |

| Watching educational television programs boosts cognitive skills. | 3-6 years | Belief that specific TV shows designed for learning can significantly enhance cognitive abilities. | Media advertising, perceived expert recommendations. |

| Reading aloud to children significantly improves their vocabulary and reading comprehension. | 0-8 years | Belief that shared reading experiences directly contribute to language development and literacy skills. | Personal experience, educational recommendations. |

Examples of Informal Theories Regarding Socio-Emotional Development

Parental beliefs about socio-emotional development profoundly shape a child’s self-esteem and social skills. Here are three examples, along with potential positive and negative consequences.

- Informal Theory: Children need to learn to “toughen up” and handle social challenges independently.

- Positive Consequence: Fosters resilience and independence in children.

- Negative Consequence: May lead to children feeling unsupported and unable to seek help when needed, potentially hindering emotional regulation.

- Informal Theory: Praising a child’s effort rather than their inherent abilities fosters self-esteem.

- Positive Consequence: Encourages a growth mindset and persistence in the face of challenges.

- Negative Consequence: May lead to children feeling inadequate if their efforts don’t always result in success.

- Informal Theory: Social skills are best learned through interactions with peers.

- Positive Consequence: Provides opportunities for children to develop social competence naturally.

- Negative Consequence: May leave children lacking in social skills if they lack positive peer interactions or if they experience bullying or social exclusion.

Examples of Informal Theories Regarding Physical Development

Parents’ beliefs about physical development influence their approach to physical activity and motor skill development. The following examples highlight the nature versus nurture debate.

- Informal Theory: Motor skills develop naturally through maturation; little intervention is needed. (Nature-focused)

- Informal Theory: Early exposure to various physical activities significantly enhances motor skill development. (Nurture-focused)

- Informal Theory: Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in athletic ability. (Nature-focused)

Impact of “Children Learn Best Through Play” on Parenting Styles

The belief that children learn best through play significantly impacts parenting styles concerning screen time and structured activities. Let’s examine this across three parenting styles:Authoritative parents, who value open communication and age-appropriate autonomy, might incorporate play-based learning into their children’s lives, while still setting reasonable limits on screen time and structured activities. Authoritarian parents, prioritizing obedience and control, may limit playtime, emphasizing structured learning and academic achievements, potentially overlooking the cognitive and social-emotional benefits of play.

Permissive parents, who are lenient and prioritize their children’s happiness, might allow excessive screen time and minimize structured activities, potentially hindering the development of self-discipline and academic skills.

Impact of Parental Beliefs About Genetics and Intelligence on Educational Approaches

Parental beliefs about the role of genetics in intelligence significantly influence their approach to education. Parents who believe intelligence is largely determined by genetics might be less likely to actively intervene in their child’s education, assuming their child’s academic success is predetermined. Conversely, parents who believe intelligence is malleable through effort and learning are more likely to provide extensive support, tutoring, and enrichment activities.

Impact of “Children Need to be Pushed to Achieve” on Parenting Styles

The belief that children need to be pushed to achieve significantly impacts parenting styles related to discipline and setting expectations.This belief, if implemented poorly, can lead to increased pressure on the child, resulting in anxiety, decreased intrinsic motivation, and lowered self-esteem. Conversely, a balanced approach, where children are challenged but also supported and encouraged, can foster resilience, ambition, and a strong sense of self-efficacy.

Informal Theories and Personal Beliefs

Informal theories, those implicit and often unexamined beliefs we hold about human behavior, are profoundly shaped by our unique life experiences and cultural immersion. These personal lenses significantly influence how we interpret the world and the people around us, often without conscious awareness. Understanding this interplay between personal experience, culture, and informal theory formation is crucial for recognizing biases and developing more nuanced perspectives.Personal Experiences Shape Informal TheoriesOur individual journeys, filled with triumphs and setbacks, successes and failures, directly contribute to the development of our informal psychological theories.

For instance, someone repeatedly betrayed by friends might develop an informal theory that people are inherently untrustworthy, leading them to approach new relationships with suspicion. Conversely, someone who has consistently experienced kindness and support may hold an informal theory emphasizing the inherent goodness of humanity. These experiences, both positive and negative, act as powerful data points, shaping our implicit understanding of human behavior and relationships.

The strength of these informal theories is often proportional to the intensity and frequency of the experiences that formed them. A single traumatic event, for example, can have a disproportionately large impact on shaping a person’s informal theories about safety and security.Cultural Background Influences Informal TheoriesCulture acts as a powerful filter, shaping not only our observable behaviors but also our underlying beliefs about the human mind.

For example, collectivist cultures, which prioritize group harmony and interdependence, may foster informal theories emphasizing social cohesion and the importance of conformity. Individuals raised in such cultures might implicitly believe that individual needs should be subordinated to the needs of the group. In contrast, individualistic cultures, which emphasize personal achievement and independence, may nurture informal theories that prioritize self-reliance and competition.

People from individualistic cultures might unconsciously believe that success is primarily a function of individual effort and ambition. These cultural influences are often deeply ingrained and may operate outside of conscious awareness, impacting our interpretations of social interactions and individual behavior.

Comparison of Informal Theories about Attachment

The following table compares and contrasts three different informal theories about attachment styles, illustrating how personal experiences and cultural backgrounds can shape these beliefs.

| Informal Theory | Description | Potential Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Secure Attachment is the Norm | Most people develop secure attachments, characterized by trust and emotional availability. Insecure attachments are exceptions. | Positive childhood experiences with consistent caregivers; a cultural emphasis on stable family structures. |

| Insecure Attachment is Inevitable | Most people will experience difficulties in forming secure attachments due to inherent human flaws or societal pressures. | Negative personal experiences with relationships; a cynical worldview; a culture that de-emphasizes emotional intimacy. |

| Attachment Styles are Malleable | Attachment styles are not fixed; they can change throughout life based on experiences and conscious effort. | Belief in personal growth and self-improvement; exposure to therapeutic approaches emphasizing attachment; a cultural emphasis on adaptability. |

The Role of Intuition in Informal Theories

Informal theories, while lacking the rigor of formal scientific models, play a crucial role in our daily understanding of the world and the behavior of others. Intuition, a rapid, often unconscious process of judgment, forms the bedrock of many of these informal theories. Understanding the role of intuition in shaping and maintaining these theories is key to appreciating both their strengths and limitations.

Intuition’s Role in Forming and Maintaining Informal Theories

The formation of intuitive theories involves a complex interplay of cognitive processes. Pattern recognition allows us to identify recurring sequences in events and behaviors, leading to the development of simplified mental models of how things work. Heuristics, or mental shortcuts, further streamline this process, enabling quick judgments even with limited information. For instance, recognizing a frown on someone’s face as a signal of displeasure is a pattern recognition process that informs our intuitive theory about emotional expression.

Similarly, using the availability heuristic – judging the likelihood of an event based on how easily examples come to mind – might lead someone to believe that plane crashes are more common than car accidents due to the vividness of news reports. These processes manifest constantly in our daily interactions, shaping our expectations and interpretations of social situations.Personal experiences, biases, and cultural factors profoundly influence the development of intuitive theories.

A person raised in a collectivist culture might develop intuitive theories about social harmony and group cooperation that differ significantly from those developed by someone from an individualistic culture, where independence and self-reliance are emphasized. For example, someone who has had many negative experiences with strangers might develop an intuitive theory that most strangers are untrustworthy, a bias that could affect their interactions.

These individually shaped theories, often implicit and unexamined, differ substantially from formal theories, which are explicitly defined, tested rigorously, and revised based on empirical evidence. Formal theories rely on systematic data collection, statistical analysis, and peer review for validation, whereas intuitive theories are validated subjectively through personal experience and informal feedback. Consequently, the predictive power of formal theories is generally stronger and more reliable than that of intuitive theories.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Relying on Intuition

Intuition, while potentially biased, offers significant benefits in certain contexts. In situations demanding rapid decision-making, such as emergency response or high-stakes negotiations, intuitive judgments can be remarkably efficient and effective. Expert judgment, often relying on years of experience and pattern recognition, frequently outperforms formal models in specific domains. For example, a seasoned firefighter’s intuitive assessment of a burning building’s structural integrity might be far faster and more accurate than a detailed engineering analysis.

The benefit here is speed, potentially saving lives. However, this speed comes at a cost.Over-reliance on intuition can lead to various biases that distort our understanding. Confirmation bias, the tendency to seek out information confirming pre-existing beliefs and ignore contradictory evidence, can reinforce inaccurate intuitive theories. For instance, someone who believes that all members of a particular group are dishonest might selectively remember instances supporting this belief while overlooking evidence to the contrary.

The availability heuristic, as mentioned earlier, can also lead to inaccurate judgments, as readily available information may not accurately reflect the true frequency of events. Anchoring bias, where initial information disproportionately influences subsequent judgments, can further skew our understanding. For example, if someone’s initial impression of a person is negative, this impression might anchor their subsequent judgments, making it difficult to see positive qualities.

These biases can have significant consequences, leading to poor decisions, misinterpretations of behavior, and prejudiced attitudes.

Intuition Leading to Accurate and Inaccurate Understandings of Behavior

Intuition can indeed lead to surprisingly accurate predictions and explanations of behavior, particularly in familiar social contexts. For instance, someone adept at reading nonverbal cues might accurately predict a friend’s emotional state based on subtle facial expressions or body language. This accuracy stems from extensive experience and the development of finely-tuned intuitive models of human behavior. The underlying mechanism involves rapid pattern recognition and the application of learned social rules.However, relying solely on intuition can lead to demonstrably flawed understandings.

Stereotypes, for instance, are intuitive theories about groups of people that are often oversimplified, inaccurate, and based on limited or biased information. The cognitive processes underlying stereotype formation include generalization from limited experience, the availability heuristic, and confirmation bias. For example, a stereotype that “all members of group X are lazy” might be based on encounters with a few lazy individuals from group X, while ignoring many hardworking members of the same group.

Such inaccuracies can have serious consequences, perpetuating prejudice and discrimination.

Comparative Analysis

| Feature | Intuitive Theory Formation | Formal Theory Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Personal experience, anecdotal evidence, heuristics | Empirical data, systematic observation, experimentation |

| Validation Method | Subjective assessment, gut feeling, informal feedback | Statistical analysis, peer review, replication of results |

| Predictive Power | Often limited, prone to biases | Generally stronger, subject to ongoing refinement |

| Speed | Rapid | Slower, more deliberate |

Case Study: Procrastination

Consider an individual who consistently procrastinates. Their intuitive theory might be that procrastination stems from a lack of willpower or self-discipline. This theory is based on personal experience and observation of their own behavior. However, this intuitive theory neglects other potential factors, such as task aversiveness, perfectionism, or poor time management skills. A formal approach, involving surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis, might reveal a more nuanced understanding of procrastination, incorporating various psychological and environmental factors.

Such an approach could lead to more effective strategies for overcoming procrastination.

Informal Theories and Scientific Method

Informal theories, those everyday understandings of the world we develop through experience, often stand in contrast to the rigorous processes of formal scientific theorizing. However, rather than being mutually exclusive, these two approaches can complement each other, with informal theories providing fertile ground for scientific inquiry and the scientific method offering a pathway to refine and test those initial intuitions.

Understanding this interplay is crucial for advancing psychological knowledge.The development of informal and formal theories follows distinct paths. Informal theories emerge organically from personal experiences, observations, and cultural influences. They are often implicit, meaning we may not consciously articulate them, and they are rarely subjected to systematic testing. In contrast, formal theories are explicitly stated, systematically developed, and rigorously tested using the scientific method.

This involves formulating hypotheses, designing studies, collecting and analyzing data, and revising the theory based on the findings. The key difference lies in the systematic and empirical approach that characterizes formal scientific theory development.

Refining Informal Theories Using the Scientific Method

The scientific method provides a powerful tool for refining informal theories. Consider a common informal theory: “People who smile more are happier.” This intuition, based on everyday observation, can be investigated scientifically. First, we would need to operationalize “smiling” and “happiness,” defining measurable variables such as frequency of smiling and scores on a standardized happiness scale. Then, we could design a study, perhaps a correlational study measuring smiling frequency and happiness levels in a sample of individuals.

If the data supports a positive correlation, the informal theory gains some empirical support. However, the scientific method also encourages further investigation to explore causality and rule out alternative explanations. For example, is smiling a cause of happiness, a consequence of it, or are both influenced by a third factor, such as social support? Further studies, perhaps experimental designs, could help address these questions and refine the initial informal theory into a more nuanced and accurate formal theory.

Potential Areas Where Informal Theories Can Inform Future Research

Informal theories, despite their limitations, can be valuable sources of inspiration for scientific research. They often reflect commonly held beliefs and intuitions about human behavior, identifying areas where formal investigation is needed. For instance, many people hold an informal theory that “stress leads to poor health.” This everyday observation can guide researchers to investigate the relationship between stress and various health outcomes, leading to the development of formal theories about the stress-illness connection.

Similarly, informal theories about effective parenting styles, the impact of social media on mental health, or the dynamics of romantic relationships can spark important lines of inquiry. By systematically examining these intuitive understandings, psychologists can move beyond anecdotal evidence and develop robust, empirically-supported formal theories.

Limitations of Informal Theories

Informal theories, while offering valuable insights and shaping our understanding of the world, are susceptible to significant limitations that can lead to inaccurate conclusions and even harmful consequences. Understanding these limitations is crucial for developing more robust and reliable explanations of human behavior and experience. This section will delve into three key areas where informal theories often fall short: the dangers of anecdotal evidence, the influence of confirmation bias, and the potential for perpetuating harmful stereotypes.

The Dangers of Relying on Anecdotal Evidence in Forming Informal Theories

Anecdotal evidence, relying on personal stories and isolated instances, forms the bedrock of many informal theories. However, this approach is fundamentally flawed due to its inherent limitations in sample size, representativeness, and susceptibility to outliers. The lack of systematic data collection and rigorous analysis renders anecdotal evidence unsuitable for drawing generalizable conclusions.

- Sample Size: Anecdotal evidence typically involves a tiny sample size, often just one or two instances. This severely limits the generalizability of any conclusions drawn. A single positive outcome, for example, doesn’t prove a treatment is effective for everyone.

- Representativeness: The individuals or events cited in anecdotal evidence are rarely representative of a larger population. A successful entrepreneur’s story might not reflect the experiences of most aspiring business owners.

- Outliers: Extreme or unusual cases can disproportionately influence conclusions based on anecdotal evidence. One exceptionally successful student doesn’t negate the challenges faced by many others.

Here are three examples of flawed informal theories stemming from anecdotal evidence:

- Social Sciences: Anecdotal evidence of successful self-help techniques, often shared through personal testimonials, leads to the informal theory that these techniques are universally effective. However, rigorous research often fails to support these claims, revealing a lack of generalizability and potentially harmful reliance on unproven methods.

- Medicine: The belief that a specific herbal remedy cures a particular illness, based solely on individual reports of improvement, is a common example. This informal theory ignores the placebo effect, the possibility of spontaneous remission, and the lack of controlled studies to establish efficacy and safety.

- Personal Finance: The informal theory that investing in a specific stock because a friend made a profit, ignoring market analysis and risk assessment, demonstrates the dangers of relying on isolated examples. This can lead to significant financial losses for those who follow such advice.

The lack of rigorous data collection and analysis inherent in anecdotal evidence directly impacts the validity and generalizability of informal theories. Without systematic data gathering, statistical analysis, and controls for confounding variables, any conclusions remain speculative and potentially misleading.

Confirmation Bias and the Evaluation of Informal Theories

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out, interpret, and recall information that confirms pre-existing beliefs, while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. This cognitive bias significantly impacts the evaluation of informal theories, leading to their reinforcement even in the face of contrary data.

The mechanism of confirmation bias involves a selective filtering process. Our brains prioritize information consistent with our beliefs, making it more accessible and memorable, while actively suppressing or reinterpreting information that challenges those beliefs.

- Social Context: Someone holding an informal theory that a particular ethnic group is inherently lazy might selectively focus on instances supporting this belief, while overlooking examples that contradict it. They might interpret ambiguous behaviors as evidence of laziness, while ignoring instances of hard work and diligence.

- Scientific Context: A researcher with a preconceived notion about the effectiveness of a new drug might design a study that inadvertently favors the desired outcome, potentially leading to biased results and the reinforcement of their informal theory despite flaws in the methodology.

- Personal Belief System: An individual believing in the power of positive thinking might selectively remember instances where positive thinking led to positive outcomes, while forgetting or minimizing situations where it didn’t, thereby reinforcing their belief.

To mitigate confirmation bias, it’s essential to actively seek out disconfirming evidence. This involves consciously looking for information that contradicts the informal theory and rigorously testing it. Blind testing methodologies, where researchers are unaware of the treatment condition, can help reduce bias in experimental settings.

The Potential for Informal Theories to Perpetuate Harmful Stereotypes

Harmful stereotypes are oversimplified and often negative generalizations about groups of people based on characteristics like race, gender, or religion. These generalizations can lead to prejudice and discrimination. Examples include the stereotype that all members of a particular racial group are inherently criminal or that women are less capable than men in leadership roles.

Informal theories, based on limited or biased observations, can significantly contribute to the formation and reinforcement of harmful stereotypes. The lack of rigorous data analysis allows biased perceptions to solidify into seemingly credible explanations.

- Example 1: The informal theory that individuals from a specific socioeconomic background are less intelligent, based on anecdotal observations of limited educational attainment in that group, ignores systemic factors such as unequal access to quality education and resources that contribute to these disparities.

- Example 2: The informal theory that a particular religious group is inherently violent, based on isolated incidents of extremism, ignores the vast majority of peaceful and law-abiding members of that group, leading to unwarranted prejudice and discrimination.

- Example 3: The informal theory that women are naturally less assertive than men, based on limited observations of gender roles in specific contexts, ignores the impact of societal expectations and biases that shape individual behavior.

Perpetuating harmful stereotypes through informal theories has severe societal consequences. It can lead to systemic discrimination, limiting opportunities and creating barriers to social justice and equality. The impact on individual well-being can be devastating, leading to feelings of marginalization, reduced self-esteem, and mental health issues. For instance, the stereotype of women being less capable in leadership roles can prevent qualified women from advancing in their careers, hindering both individual and organizational success.

Similarly, racial stereotypes can lead to biased hiring practices and unequal access to justice.

Identifying and challenging informal theories that perpetuate harmful stereotypes requires critical self-reflection, active listening to diverse perspectives, and a commitment to seeking evidence-based understanding. This includes acknowledging personal biases, actively seeking out diverse viewpoints, and engaging in open and respectful dialogue to challenge inaccurate generalizations.

The Use of Informal Theories in Everyday Life

Informal theories, those implicit and often unconscious understandings of the world, are the unsung heroes of our daily navigation. They’re the mental shortcuts and ingrained beliefs that guide our decisions, shape our problem-solving approaches, and influence how we interact with others. Understanding their role is key to understanding ourselves and our behaviors.Informal theories profoundly impact our everyday decision-making processes.

We constantly make choices based on our intuitive grasp of cause and effect, often without consciously analyzing the evidence. For example, choosing a restaurant might be based on a generalized belief (“Italian food is always good”) rather than a detailed evaluation of specific reviews. Similarly, deciding whether to trust someone might hinge on an informal theory about body language (“crossed arms indicate defensiveness”) or personality traits (“people who smile a lot are friendly”).

These judgments, while often effective, can also lead to biases and inaccurate assessments.

Informal Theories and Decision-Making

Our informal theories act as filters, shaping how we interpret information and influencing the choices we make. Consider the classic example of confirmation bias: we tend to seek out and interpret information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs, while dismissing information that contradicts them. This is a direct consequence of our reliance on informal theories. If we believe, for instance, that a particular political party is always right, we might only read news sources that support this belief, reinforcing our existing informal theory and potentially leading to poor decision-making.

Another example could be choosing a career path based on a generalized belief about a certain profession (“doctors make a lot of money”), overlooking the realities of long hours and intense pressure. These decisions are not necessarily irrational; they are simply influenced by our deeply ingrained informal theories.

Informal Theories and Problem-Solving

Informal theories also significantly influence how we approach problem-solving. Our ingrained beliefs about how things work often determine the strategies we employ. For instance, if someone believes that “hard work always pays off,” they might persist with a difficult task even when other approaches might be more efficient. Conversely, a belief that “luck is the most important factor” might lead to a more passive problem-solving approach, relying on chance rather than strategic planning.

These different approaches, stemming from distinct informal theories, demonstrate how our implicit beliefs shape our actions and outcomes. The effectiveness of these approaches varies widely depending on the nature of the problem and the accuracy of the underlying informal theory.

Informal Theories and Social Interactions

Navigating the complexities of social interactions heavily relies on informal theories. Our understanding of social cues, like facial expressions and body language, is largely based on implicit theories learned through observation and experience. These theories guide our responses in social situations, allowing us to predict and react to others’ behavior. For example, understanding the informal theory that “making eye contact shows engagement” guides our interactions in conversations and meetings.

Similarly, understanding the informal theory that “giving compliments builds rapport” can influence how we approach new people. However, these informal theories can also lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations, as cultural differences and individual variations can significantly alter the meaning of social cues.

Informal Theories and Professional Practice: What Are Examples Of An Informal Theory In Psychology

Informal theories, while not explicitly stated or rigorously tested, profoundly shape the actions and decisions of mental health professionals. Understanding their influence is crucial for ethical and effective practice. This section delves into the impact of informal theories on professional practice, ethical considerations, and methods for critical evaluation.

Detailing the Influence of Informal Theories

The pervasive nature of informal theories in professional practice necessitates a detailed examination of their influence. These implicit beliefs and assumptions, often shaped by personal experiences and cultural contexts, can significantly affect therapeutic relationships, diagnostic processes, and treatment planning.

Specific Examples of Informal Theory Influence

The following table illustrates how informal theories impact professional practice across various aspects of mental health work.

| Informal Theory | Professional Practice Impacted | Potential Impact on Client |

|---|---|---|

| Belief that clients from marginalized communities are inherently less resilient. | Lower expectations for treatment progress, less investment in therapeutic alliance. | Negative; client may receive less effective treatment, experience feelings of devaluation, and experience diminished self-efficacy. |

| Assumption that certain presenting problems are primarily rooted in biological factors, neglecting psychosocial aspects. | Over-reliance on medication, insufficient exploration of environmental and relational influences. | Potentially negative; may lead to incomplete treatment, overlooking important contextual factors contributing to the problem, and reliance on a solely biomedical approach which might be insufficient. |

| Belief that a specific therapeutic technique (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) is universally superior for all clients. | Rigid adherence to a single approach, neglecting client preferences and tailoring treatment to individual needs. | Potentially negative; may lead to treatment resistance, poor client engagement, and ultimately, treatment failure if the approach is not a good fit for the client. A positive impact is possible if the chosen therapy is indeed the most effective for that client. |

Comparison Across Disciplines

The influence of informal theories varies across mental health professions due to differences in training, ethical guidelines, and practice settings. For instance, psychiatrists, with their medical training, might be more inclined to rely on biomedical models, potentially overlooking psychosocial factors. Conversely, social workers, with their emphasis on social determinants of health, might prioritize systemic interventions, potentially underestimating the role of individual factors.

Examples of informal theories in psychology often emerge from clinical observations and lack the rigorous testing of formal hypotheses. A similar concept applies to image processing, where intuitive approaches, such as those used in a weak light relighting algorithm based on prior knowledge , might initially rely on heuristic rules before formal mathematical models are developed. These intuitive, pre-formalized approaches, much like informal theories in psychology, offer a starting point for more systematic investigation.

Psychologists, integrating various perspectives, may be more susceptible to biases depending on their specific theoretical orientation. Ethical codes, while aiming for objectivity, cannot completely eliminate the influence of these implicit biases. Differences in practice settings (e.g., inpatient vs. outpatient) also influence the weight given to informal theories; time constraints in busy settings may increase reliance on quick assessments and established routines, which may be influenced by informal theories.

Ethical Considerations of Informal Theories

The reliance on informal theories presents several ethical challenges, demanding careful consideration. Transparency and self-awareness are paramount in mitigating potential harm.

Case Study Analysis of an Ethical Dilemma

Imagine a therapist holding an informal theory that individuals experiencing homelessness lack the motivation to change. This belief might lead to less effort in collaborative goal setting, a less empathetic therapeutic approach, and a diminished expectation of success. This violates the APA Ethical Principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, potentially leading to the client feeling judged and receiving inadequate support.

Adhering to the informal theory could perpetuate harmful stereotypes and hinder the client’s progress; disregarding it would promote a more equitable and effective therapeutic relationship.

Informed Consent and Informal Theories

Obtaining truly informed consent is complicated by the presence of informal theories. Completely disclosing all personal biases and assumptions is difficult, yet crucial for respecting client autonomy. It requires ongoing self-reflection and a commitment to transparency, where possible, about the therapist’s approach.

Supervision and Peer Review

Supervision and peer review provide vital mechanisms for identifying and addressing the influence of informal theories. These processes offer opportunities for self-reflection, feedback, and the application of ethical frameworks to professional practice. Regular supervision allows for critical examination of clinical decisions and helps to challenge potentially harmful biases.

Critical Evaluation of Informal Theories

Rigorous evaluation is crucial to minimize the negative impact of informal theories and maximize the benefits of clinical intuition.

Research Methodology for Evaluating Informal Theories

Qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis of clinical notes or interviews with practitioners, can uncover prevalent informal theories. Quantitative methods, such as surveys measuring therapist beliefs and correlating them with client outcomes, can assess the impact of these theories. However, establishing causality is challenging due to the complex interplay of factors in therapeutic relationships.

Bias Identification and Mitigation

A systematic process for identifying and mitigating biases involves regular self-reflection, seeking feedback from colleagues, and utilizing structured clinical decision-making tools. This process is ongoing and requires commitment to continuous improvement. Specific techniques include reflective journaling, blind rating of case materials, and utilizing standardized assessment measures to minimize subjective interpretations.

Evidence-Based Practice and Informal Theories

Integrating evidence-based practice with informal theories requires a critical approach. Empirical research can support or refute specific informal theories, leading to refinements in practice. For example, research on the effectiveness of different therapeutic approaches can inform the choice of treatment, reducing reliance on unsubstantiated beliefs about therapeutic efficacy.

Examples of Informal Theories in Popular Culture

Popular culture, encompassing movies, television shows, and books, is rife with informal theories about psychology. These portrayals, while often entertaining, frequently present simplified or inaccurate representations of complex psychological concepts, significantly impacting public understanding and shaping perceptions of mental health and behavior. These informal theories, often presented implicitly through character actions and plotlines, can either reinforce existing stereotypes or introduce entirely new, potentially misleading, interpretations of psychological phenomena.

The pervasive nature of these informal theories necessitates critical analysis. By examining specific examples, we can better understand how media shapes public perception and identify potential areas for improved psychological literacy.

Portrayals of Mental Illness in Film and Television

Many films and television shows depict mental illness, often employing stereotypes that are both inaccurate and potentially harmful. For instance, the portrayal of individuals with schizophrenia as violent and unpredictable, frequently seen in action movies or thrillers, reinforces negative stereotypes and contributes to stigma. Conversely, some portrayals focus solely on the dramatic aspects of mental illness, neglecting the nuances of lived experience and the complexities of treatment.

The movie “A Beautiful Mind,” while showcasing the struggles of John Nash with schizophrenia, also romanticizes his experience and doesn’t fully represent the challenges faced by many individuals with this condition. Similarly, many shows utilize “manic pixie dream girl” tropes, which often reduce complex emotional and mental health issues to quirky personality traits, trivializing the seriousness of these conditions.

The Use of Psychological Concepts in Crime Dramas

Crime dramas frequently incorporate psychological concepts, albeit often in a simplified and sometimes inaccurate manner. Profiling, for example, is often depicted as a highly accurate and intuitive process, relying heavily on the profiler’s insight rather than scientific methodology. This can lead viewers to believe that profiling is a more precise science than it actually is, overestimating its accuracy and reliability.

Shows like “Criminal Minds” often present simplified versions of psychological assessments and diagnostic procedures, potentially leading to misinterpretations of the complexities involved in understanding criminal behavior. The emphasis on dramatic effect often overshadows the scientific rigor necessary for accurate profiling and psychological assessment.

The Influence of Popular Self-Help Books

Self-help books often present simplified, and sometimes unsupported, psychological theories. While some offer valuable insights and practical advice, others may promote quick fixes or unsubstantiated claims, potentially misleading readers about effective strategies for personal growth or addressing mental health concerns. Many books focus on single, easily digestible concepts, neglecting the interconnectedness of various psychological factors that influence behavior and well-being.

This can lead to an oversimplification of complex issues and a potentially harmful reliance on simplistic solutions for complex problems. The lack of scientific evidence backing some self-help claims underscores the need for critical evaluation of such material.

Bridging the Gap Between Informal and Formal Theories

Informal theories, born from everyday observations and intuitions, often serve as fertile ground for scientific inquiry. They represent our initial attempts to make sense of the world, providing a valuable starting point for the development of rigorous, testable hypotheses and formal theories. This section explores the crucial process of translating these informal notions into the structured framework of formal research, highlighting the iterative nature of this relationship.

Using Informal Theories to Generate Testable Hypotheses

Informal theories, while lacking the precision of formal theories, can be remarkably insightful. Their intuitive nature allows for the identification of potential relationships and patterns that might otherwise be missed. By systematically refining these initial observations, we can formulate testable hypotheses that advance our understanding.

Examples of Informal Theory Translation into Falsifiable Hypotheses

The transformation of informal observations into falsifiable hypotheses involves a careful process of operationalization and refinement. Let’s consider three examples:

- Psychology: Informal Observation: People tend to remember information better if it’s emotionally charged. Hypothesis: Participants will recall more words from a list if those words are associated with emotionally evocative images compared to neutral images. Variables: Independent variable – type of image (emotional vs. neutral); Dependent variable – number of words recalled.

- Economics: Informal Observation: Scarcity increases perceived value. Hypothesis: Consumers will be willing to pay more for a product if it is advertised as limited edition compared to an identical product without scarcity messaging. Variables: Independent variable – scarcity messaging (present vs. absent); Dependent variable – price consumers are willing to pay.

- Physics: Informal Observation: Objects fall at different speeds depending on their weight. (This is an example of an

incorrect* informal theory, useful for illustrating the process). Hypothesis

Heavier objects will fall faster than lighter objects when dropped from the same height in a vacuum. Variables: Independent variable – object weight; Dependent variable – time taken to fall.

Operationalizing Concepts from Informal Theories

Transforming the vague concepts within informal theories into measurable variables is a crucial step. This process typically involves:

- Clearly defining the concepts: Specify exactly what is meant by each term in the informal theory.

- Identifying measurable indicators: Determine how each concept can be measured using quantifiable data (e.g., scales, counts, timings).

- Developing operational definitions: Create precise definitions that specify the procedures used to measure each variable.

- Selecting appropriate measurement tools: Choose instruments that accurately and reliably capture the intended variables.

Limitations of Using Informal Theories as a Basis for Formal Research

While informal theories are valuable starting points, they are prone to biases and limitations. Confirmation bias, for example, might lead to selective attention to evidence supporting the informal theory while ignoring contradictory evidence. Overgeneralization from limited observations is another common pitfall. These limitations can be mitigated through rigorous research design, including the use of control groups, random assignment, and objective measurement techniques.

Furthermore, acknowledging potential biases and actively seeking out disconfirming evidence can help to minimize their impact.

Informal theories in psychology, such as personal beliefs about human behavior, often lack rigorous testing. For instance, a common belief might posit that certain personality traits predict success, a concept that could be explored further by considering practical applications; the question of resourcefulness, as examined in the article ” could you make shelter in theory yes “, highlights the interplay between theoretical constructs and real-world challenges.

This ultimately underscores the need for formal research to validate these informal psychological theories.

Refining Informal Theories with Research Findings

Empirical research plays a vital role in refining and improving informal theories. By comparing the predictions of an informal theory with the results of multiple studies, we can identify discrepancies and areas for improvement.

Case Study: The Bystander Effect

The bystander effect, the observation that individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present, initially stemmed from informal observations. Early research, however, revealed the complexities of this phenomenon, showing that factors such as ambiguity, diffusion of responsibility, and the presence of others influence helping behavior. This led to a refined understanding of the bystander effect, moving beyond the simple initial observation.

Comparative Analysis of Informal Theory and Research Findings

A comparative analysis can reveal where an informal theory aligns with empirical evidence and where it needs revision. Consider the informal theory that “people are more likely to conform to group pressure when the group is larger.” Research has shown that conformity increases with group size, but only up to a certain point; beyond that, the effect plateaus.

This discrepancy necessitates a modification of the informal theory to account for this limit.

Case Studies

Case studies offer a powerful lens through which to examine the practical implications of informal theories. By exploring real-world scenarios, we can observe how deeply ingrained beliefs shape individual perceptions, decisions, and ultimately, life outcomes. Let’s delve into a hypothetical example to illustrate this point.

The following case study highlights how an individual’s informal theory about success influenced their career path and overall well-being.

The Case of Sarah and the “Success Myth”

Sarah, a highly intelligent and creative young woman, held a deeply ingrained informal theory about success: she believed that success equated solely with high-powered corporate positions and significant financial wealth. This belief, fostered by societal narratives and the observations of her ambitious parents, shaped her choices from a young age. She relentlessly pursued a demanding career in finance, sacrificing personal relationships and hobbies in the process.

She consistently prioritized work over leisure, believing that any deviation from this path would indicate a lack of commitment and jeopardize her chances of “true” success. Despite achieving impressive professional milestones, including a senior management role, Sarah consistently felt dissatisfied and unfulfilled. She experienced high levels of stress and anxiety, leading to burnout and a sense of isolation.

Her relationships suffered, and her physical health deteriorated.

A more formal understanding of psychology, specifically positive psychology and self-determination theory, might have offered Sarah a different perspective. These frameworks emphasize the importance of intrinsic motivation, autonomy, and relatedness in achieving well-being. A formal understanding could have helped Sarah recognize that her definition of success was limited and potentially detrimental to her overall happiness. It might have encouraged her to explore alternative paths that aligned better with her values and intrinsic motivations, perhaps finding fulfillment in a less demanding but more personally rewarding career, or prioritizing work-life balance and cultivating stronger social connections.

The contrast between Sarah’s experience and a more balanced approach underscores the limitations of relying solely on informal, often narrowly defined, theories of success.

Expert Answers

Q: Can informal theories be helpful?

A: Absolutely! They provide quick, intuitive explanations that can guide our everyday interactions and decisions. They can also serve as a starting point for generating formal research hypotheses.

Q: How do I identify my own informal theories?

A: Pay attention to your gut reactions and assumptions about people’s behavior. Ask yourself: Why do I believe this? What experiences shaped this belief? Are there exceptions to this rule?

Q: Are informal theories always bad?

A: No, they’re not inherently bad. The issue arises when we treat them as absolute truths without critical evaluation or empirical testing. Recognizing their limitations is key.

Q: How do informal theories differ from folk psychology?

A: Folk psychology refers to the common-sense understanding of the mind and behavior shared within a culture. Informal theories are a subset of this, representing individual beliefs and assumptions.