What are ethical theories? This question delves into the fascinating world of moral philosophy, exploring diverse frameworks that guide our understanding of right and wrong. From ancient Greek philosophers to contemporary thinkers, ethical theories have shaped our societies and continue to grapple with the complex moral dilemmas of our time. We’ll explore different perspectives, including utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics, examining their core principles, strengths, and limitations.

Understanding these theories provides a valuable framework for navigating ethical challenges in our personal lives and the broader world.

This exploration will cover the historical development of ethical thought, highlighting key figures and their contributions. We will then delve into a comparative analysis of major ethical frameworks, examining their core principles and applications. Finally, we’ll address how to apply these frameworks to real-world situations, considering the influence of biases and emotions on ethical decision-making. The goal is to equip you with a solid understanding of ethical theories and their practical implications.

Introduction to Ethical Theories

Ethics and morality are fundamental to human existence, guiding our actions and shaping our societies. Understanding the difference between descriptive and normative ethics is crucial to navigating this complex landscape.

Descriptive and Normative Ethics

Descriptive ethics focuses on describing and explaining moral beliefs and practices in different societies and cultures. It’s an empirical study, observing what people

- do* believe is right or wrong, without judging the validity of those beliefs. For example, a descriptive ethics study might examine the varying attitudes towards euthanasia across different countries. Normative ethics, conversely, is concerned with prescribing moral principles and standards. It aims to determine what

- ought* to be considered right or wrong, good or bad. A normative ethics argument might propose a set of guidelines for determining when euthanasia is morally permissible.

Definitions of Morality

Three distinct definitions of morality highlight the multifaceted nature of the concept: 1) Morality as a set of rules and principles governing behavior, often enforced by social institutions. This definition emphasizes the external aspect of morality, focusing on conformity to societal norms. 2) Morality as a system of values and beliefs about right and wrong, good and bad, held by individuals or groups.

This definition highlights the internal aspect of morality, focusing on individual conscience and beliefs. 3) Morality as a capacity for empathy and compassion, guiding actions towards the well-being of others. This definition emphasizes the emotional and relational aspects of morality, highlighting the importance of caring for others.

Historical Overview of Ethical Thought

Ethical thought has evolved significantly throughout history, influenced by philosophical, religious, and social changes.

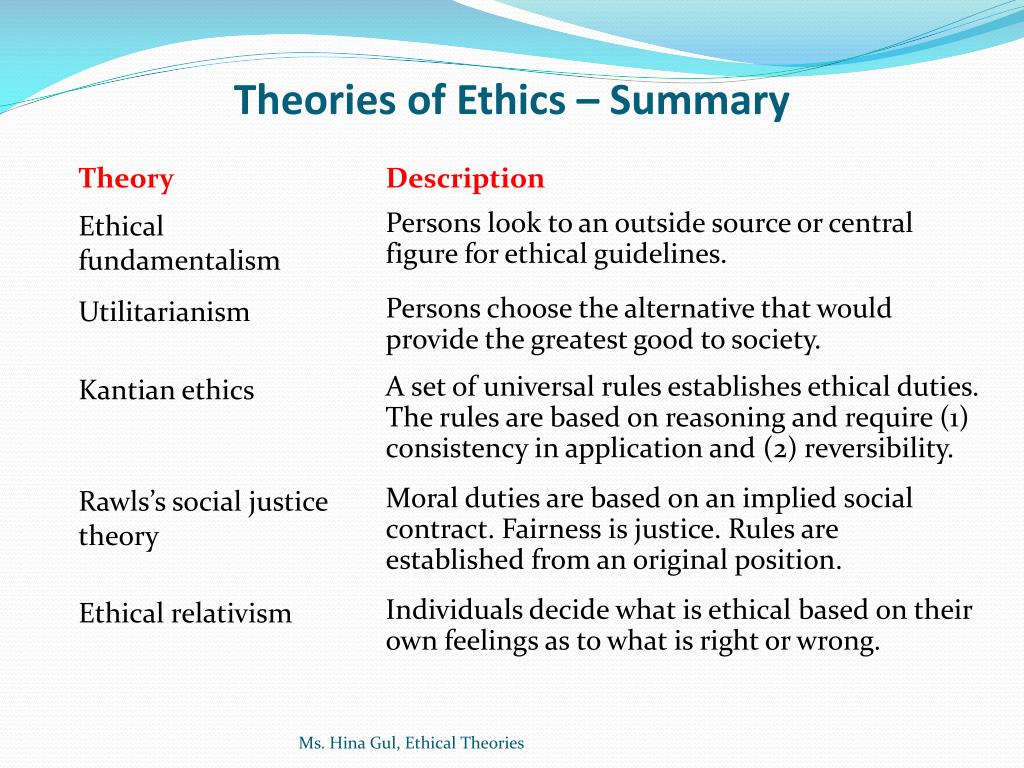

| Period | Theory | Proponent(s) | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greece (c. 600-300 BCE) | Virtue Ethics | Aristotle, Plato | Eudaimonia (flourishing), character development, virtues (courage, justice, wisdom), practical wisdom |

| Ancient Greece (c. 600-300 BCE) | Natural Law Theory | Stoics (e.g., Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius) | Inherent moral order in the universe, reason as a guide to living in accordance with nature |

| Enlightenment (17th-18th Centuries) | Utilitarianism | Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill | Maximizing happiness and well-being, consequences of actions, greatest good for the greatest number |

| Enlightenment (17th-18th Centuries) | Deontology | Immanuel Kant | Duty, moral rules, categorical imperative, universalizability, respect for persons |

| 20th Century | Existentialism | Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir | Individual freedom, responsibility, authenticity, creating meaning in a meaningless universe |

| 20th Century | Ethics of Care | Carol Gilligan | Relationships, empathy, compassion, responsibility for others, interconnectedness |

Ethical Theories in Daily Life

Ethical theories are not abstract concepts; they directly influence our daily decisions.

- Case Study 1: Whistleblower Dilemma: An employee discovers illegal activity within their company. Utilitarianism might suggest revealing the information to protect the greater good, even if it means personal risk. Deontology might emphasize the moral duty to report wrongdoing, regardless of the consequences. Utilitarianism prioritizes the outcome (minimizing harm), while deontology focuses on the action itself (fulfilling a moral obligation).

The strengths of utilitarianism lie in its focus on overall well-being, but it can be difficult to predict all consequences. Deontology provides clear moral guidelines but may lead to inflexible or harmful actions in certain contexts.

- Case Study 2: Resource Allocation in Healthcare: A hospital faces a shortage of life-saving medication. Utilitarianism might prioritize distributing the medication to those with the highest chance of survival and greatest overall benefit. Virtue ethics might emphasize the importance of fairness and compassion in making the allocation decision, potentially prioritizing vulnerable populations or those with the greatest need. Utilitarianism focuses on maximizing benefit, but may lead to difficult choices about who lives and who dies.

Virtue ethics promotes equitable treatment, but can lack a clear, consistent decision-making process.

- Case Study 3: Environmental Protection vs. Economic Growth: A company must decide between implementing environmentally friendly but more expensive practices and continuing current, less sustainable, but more profitable methods. Utilitarianism might weigh the long-term costs of environmental damage against short-term economic gains. Deontology might focus on the moral obligation to protect the environment, regardless of economic impact. Utilitarianism seeks to balance competing interests, but can be susceptible to biases and inaccurate predictions.

Deontology provides a clear moral framework but might lead to economically unsustainable actions.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism, in its simplest form, judges the morality of an action solely based on its consequences. Different actions might have varying outcomes, and consequentialist ethical theories attempt to provide frameworks for determining which actions produce the best overall results. A key branch of consequentialism is utilitarianism, which we will explore in detail.

Core Principles of Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism, a prominent consequentialist theory, centers on the principle of maximizing overall happiness or well-being. It posits that the best action is the one that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people. This “greatest good” is often understood as maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain, although different utilitarian thinkers have offered variations on this core concept. A crucial aspect is the impartial consideration of all affected individuals; no one’s happiness is inherently more valuable than another’s.

Act Utilitarianism versus Rule Utilitarianism

Act utilitarianism focuses on the consequences of individual actions. Each action is evaluated separately based on whether it produces the greatest good in that specific situation. Rule utilitarianism, conversely, emphasizes the establishment of general rules that, if followed consistently, would maximize overall happiness. Instead of assessing each action individually, it focuses on the overall beneficial consequences of adhering to these rules.Act utilitarianism’s strength lies in its flexibility; it allows for nuanced decision-making in unique circumstances.

However, its weakness is the potential for justifying actions that seem intuitively wrong if they lead to a greater overall good. Rule utilitarianism, on the other hand, provides a more stable moral framework, preventing the justification of intuitively wrong actions. Its weakness, however, lies in its rigidity; it may not adequately address exceptional circumstances where breaking a rule might produce significantly better consequences.

Challenges of Predicting Consequences

Predicting the consequences of actions is inherently difficult. Human behavior is complex, and unforeseen circumstances frequently arise. For example, a policy intended to boost economic growth might unintentionally lead to environmental damage, highlighting the challenges of accurately forecasting all potential outcomes. Furthermore, the subjective nature of “good” and “bad” consequences adds another layer of complexity. What constitutes the greatest good for one person might be detrimental to another, requiring careful consideration of diverse perspectives and potential trade-offs.

A real-life example is the introduction of a new technology; while it might bring economic benefits, its long-term environmental or social consequences might be hard to predict accurately at the outset.

A Utilitarian Dilemma

Imagine a doctor with five patients needing organ transplants to survive. A healthy individual walks into the hospital for a routine checkup. The doctor could secretly harvest this individual’s organs, saving the five patients. This would result in the death of one person but the survival of five. A utilitarian analysis would weigh the consequences: the loss of one life versus the saving of five.

However, the act is morally problematic, highlighting the tension between maximizing overall good and respecting individual rights. This scenario exemplifies the challenges of applying utilitarian principles in complex ethical dilemmas.

Deontology: What Are Ethical Theories

Deontology, unlike consequentialism, focuses on the inherent rightness or wrongness of actions themselves, regardless of their consequences. It emphasizes moral duties and rules, suggesting that some actions are inherently right or wrong, irrespective of their outcomes. This approach provides a strong framework for understanding moral obligations, but also presents unique challenges in navigating complex ethical dilemmas.

Deontological ethical frameworks offer a different lens through which to view moral decision-making, shifting the emphasis from the results of actions to the actions themselves. This perspective is particularly useful in situations where predicting outcomes is difficult or impossible, providing a set of guiding principles for behavior regardless of the potential consequences.

Key Tenets of Kantian Ethics

Kantian ethics, a prominent form of deontology, centers on the concept of the “categorical imperative.” This imperative dictates that we should only act according to principles that we could rationally will to become universal laws. In essence, we should act as if our actions were to become a standard for everyone. Another crucial element is the concept of treating individuals as “ends in themselves,” not merely as means to achieve our own goals.

This emphasizes respect for the inherent worth and autonomy of every person. Kantian ethics emphasizes rationality and consistency in moral decision-making, providing a robust framework for ethical behavior. It also highlights the importance of treating others with respect and dignity, recognizing their intrinsic value.

Comparison of Kantian Deontology with Other Deontological Frameworks

While Kantian ethics is a prominent deontological framework, others exist. For instance, Ross’s pluralism suggests a variety of prima facie duties (such as fidelity, reparation, gratitude, justice, beneficence, self-improvement, and non-maleficence) that we must consider in ethical decision-making. These duties might sometimes conflict, requiring careful consideration to determine which takes precedence in a given situation. Unlike Kant’s emphasis on a single, overarching principle, Ross’s approach acknowledges the complexity of moral life and the potential for competing obligations.

Another contrast can be found in rule deontology versus act deontology. Rule deontology emphasizes adherence to general moral rules, while act deontology focuses on the moral evaluation of individual actions in specific contexts.

The Role of Duty and Moral Obligation in Deontological Ethics

Duty and moral obligation are central to deontological ethics. Deontologists believe that we have a moral duty to act in accordance with certain principles, regardless of the consequences. This duty is often seen as stemming from reason, or from a divine command, or from our inherent nature as moral beings. The emphasis on duty provides a clear and consistent framework for ethical decision-making, particularly in situations where consequences are uncertain or difficult to predict.

However, the rigid nature of duty-based ethics can sometimes lead to conflicts between different duties, requiring careful consideration and prioritization. The weight of moral obligation, therefore, rests on the individual’s commitment to acting according to these principles.

Comparison of Consequentialism and Deontology

The following table contrasts consequentialism and deontology, highlighting their core principles, strengths, and weaknesses:

| Theory | Core Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consequentialism | The morality of an action is determined by its consequences. | Focuses on outcomes, often leading to practical solutions; adaptable to different situations. | Difficult to predict all consequences; potential for justifying harmful actions if they lead to a greater good; can neglect individual rights. |

| Deontology | The morality of an action is determined by its adherence to moral rules and duties. | Provides a clear framework for ethical decision-making; protects individual rights; emphasizes consistency and fairness. | Can be inflexible; may lead to conflicts between duties; may not always produce the best outcomes. |

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics offers a different perspective on morality compared to consequentialism and deontology. Instead of focusing on actions or rules, it emphasizes the character of the moral agent. It suggests that ethical behavior stems from cultivating virtuous character traits, leading to virtuous actions as a natural consequence. This approach emphasizes personal growth and the development of moral excellence.Virtue ethics and its role in moral decision-making.Virtue ethics centers on the idea that moral excellence is achieved through the development of virtuous character traits.

These virtues are not merely abstract concepts but dispositions to act in certain ways, guided by practical wisdom. When faced with an ethical dilemma, a virtuous person will naturally choose the course of action that aligns with their developed virtues. This is not a rigid rule-based system; instead, it relies on judgment and discernment cultivated through experience and reflection.

The decision-making process is informed by one’s character, not by a strict adherence to rules or the calculation of consequences.

Character Development in Virtue Ethics

Character development is the cornerstone of virtue ethics. It’s a lifelong process of cultivating virtuous traits and mitigating vices. This involves self-reflection, learning from experiences, and seeking guidance from mentors or role models. It’s not a passive process; it requires active engagement in shaping one’s character. For example, practicing empathy requires actively listening to others, understanding their perspectives, and responding with compassion.

Similarly, developing courage involves facing fears and challenges, gradually building resilience and confidence. The development of a virtuous character is a dynamic process, involving constant learning and growth.

Examples of Virtues and Vices and Their Relation to Ethical Actions

Virtues and vices are opposing character traits. Virtues lead to ethical actions, while vices lead to unethical actions. For instance, honesty (a virtue) leads to truthful communication and trustworthy behavior, whereas dishonesty (a vice) leads to deception and betrayal. Similarly, compassion (a virtue) motivates helping those in need, while cruelty (a vice) results in inflicting suffering. The presence of virtues in an individual generally results in ethical choices and behavior, while the dominance of vices often leads to unethical conduct.

Consider a situation where someone finds a lost wallet. A person with the virtue of honesty will return the wallet; a person with the vice of dishonesty might keep it.

Key Virtues and Their Corresponding Vices

Understanding the interplay between virtues and vices is crucial in ethical decision-making. The following list illustrates some key virtues and their corresponding vices:

- Virtue: Honesty; Vice: Dishonesty

- Virtue: Courage; Vice: Cowardice

- Virtue: Compassion; Vice: Cruelty

- Virtue: Justice; Vice: Injustice

- Virtue: Temperance; Vice: Intemperance

- Virtue: Prudence; Vice: Imprudence

- Virtue: Kindness; Vice: Callousness

- Virtue: Generosity; Vice: Greed

It is important to note that this is not an exhaustive list, and the specific virtues and vices considered important may vary across cultures and contexts. However, the underlying principle remains consistent: the cultivation of virtuous character traits is essential for ethical living.

Ethics of Care

Ethics of care offers a valuable perspective on moral decision-making, emphasizing the importance of relationships, empathy, and responsiveness to the needs of others. Unlike theories that focus on abstract principles or consequences, ethics of care grounds moral reasoning in the concrete context of human interaction. This approach recognizes the inherent interconnectedness of individuals and the profound influence of personal relationships on ethical judgments.

Principles of Ethics of Care

The core principles of ethics of care guide moral deliberation within this framework. These principles are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, emphasizing the importance of understanding and responding to the needs of others within the specific context of the relationship.

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Responsiveness to Need | Prioritizing the needs and vulnerabilities of those involved in a given situation. This involves actively listening and seeking to understand the perspectives of others, especially those who are marginalized or vulnerable. |

| Attentiveness | Paying careful attention to the details of a situation, including the emotional and relational aspects. This requires careful observation and a willingness to engage with the complexities of human experience. |

| Compassion | Feeling empathy and concern for the suffering of others. This involves a willingness to act on those feelings and to offer support and assistance. |

| Empathy | The capacity to understand and share the feelings of another person. This requires active listening, perspective-taking, and a genuine effort to connect with the emotional experience of others. |

| Importance of Particular Relationships | Recognizing that moral obligations are often shaped by the specific nature of our relationships with others. This means that our duties and responsibilities may differ depending on the context of the relationship. |

Comparative Analysis

The ethics of care offers a distinct approach to moral dilemmas compared to other ethical theories. Its emphasis on relationships and context leads to different recommendations in many situations.

| Ethical Theory | Approach to Moral Dilemmas | Divergence from Ethics of Care |

|---|---|---|

| Utilitarianism | Focuses on maximizing overall happiness and well-being. Decisions are made based on the potential consequences, aiming for the greatest good for the greatest number. | May disregard the specific needs and relationships of individuals in favor of a broader calculation of utility. For example, a utilitarian approach might justify sacrificing the well-being of a few to benefit the many, while ethics of care would prioritize the well-being of those directly affected by the decision. |

| Deontology | Emphasizes adherence to moral rules and duties, regardless of the consequences. Decisions are guided by principles such as honesty, fairness, and respect for persons. | May overlook the particular circumstances of a situation and fail to adequately consider the needs of those involved. For instance, a deontological approach might insist on following a rule even if doing so causes significant harm in a specific situation, while ethics of care would prioritize minimizing harm within the context of the relationship. |

| Virtue Ethics | Focuses on cultivating virtuous character traits, such as compassion, honesty, and courage. Moral decisions are made by considering what a virtuous person would do in a given situation. | While sharing some common ground with ethics of care in emphasizing virtues like compassion and empathy, virtue ethics may not sufficiently address the importance of specific relationships and the context-dependent nature of moral obligations. It may also offer less guidance in resolving conflicts between different virtues. |

Role of Relationships and Empathy

Relationships and empathy are central to ethical decision-making within the framework of the ethics of care. Empathy allows us to understand the perspectives and needs of others, while relationships provide the context for our moral obligations. In personal relationships, empathy informs how we respond to a friend’s distress, shaping our actions and decisions based on their needs and our shared history.

In professional relationships, empathy is crucial for effective counseling, social work, or medical care. A therapist, for instance, uses empathy to understand a patient’s emotional state and tailor their approach accordingly. However, close relationships can also introduce bias. For example, a parent might be less objective in judging their child’s actions compared to a stranger’s.

Hypothetical Scenario Design

Scenario A: Suboptimal Outcome

Ethical Dilemma: A doctor has limited doses of a life-saving medication and must choose between saving a young child or an elderly patient.Utilitarian Approach: The doctor might choose the child, maximizing the years of life saved.Deontological Approach: The doctor might follow a first-come, first-served rule or another pre-established protocol.Ethics of Care Approach: The doctor might prioritize the patient with the strongest support network, considering the impact on their family and loved ones.

This could lead to choosing the elderly patient if they have a large, supportive family, even if the child has a longer life expectancy.Conclusion: In this case, a utilitarian or deontological approach might seem more efficient, but the ethics of care highlights the relational impact of the decision and the importance of minimizing suffering for all involved.

Scenario B: Superior Solution

Ethical Dilemma: A community is facing a severe drought, and water resources are dwindling. A wealthy family has a large private well.Utilitarian Approach: Might suggest rationing water equally, regardless of need or wealth.Deontological Approach: Might emphasize the right to private property and discourage intervention.Ethics of Care Approach: Focuses on the most vulnerable members of the community—elderly, children, the sick—and might advocate for the wealthy family to share some of their water supply, recognizing their interconnectedness within the community.Conclusion: The ethics of care approach fosters cooperation and addresses the specific needs of those most vulnerable, demonstrating a more humane and effective solution than a strictly utilitarian or deontological approach.

Limitations and Criticisms

- Potential for Bias: The emphasis on relationships can lead to partiality, favoring those close to us over others. This can be mitigated by conscious reflection and efforts to remain objective.

- Difficulty in Scaling: Applying ethics of care to large-scale issues can be challenging, as it requires considering countless individual relationships. This requires developing frameworks for prioritizing needs and balancing competing claims.

- Partiality: Prioritizing close relationships can lead to neglecting the needs of others. This requires careful consideration of competing obligations and a commitment to justice.

Real-World Application

In palliative care, the ethics of care is central. Medical professionals focus not only on prolonging life but also on providing comfort and support to patients and their families, addressing their emotional and spiritual needs. This approach recognizes the importance of relationships in coping with illness and death, offering a holistic approach to care that goes beyond purely medical interventions.

Challenges include balancing the needs of the patient with those of the family, managing emotional burdens, and dealing with difficult end-of-life decisions.

Rights-Based Ethics

Rights-based ethics centers on the idea that individuals possess inherent rights that deserve protection and respect. This framework emphasizes the moral importance of upholding these rights, regardless of consequences or other ethical considerations. Understanding rights-based ethics requires a careful examination of the nature of rights themselves and their interaction with other ethical perspectives.

Human Rights: Definition and Examples

Human rights are fundamental rights inherent to all individuals, regardless of their nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. Their inherent nature stems from the belief in the inherent dignity and worth of every human being. Universality signifies that these rights apply to everyone, everywhere. Inalienability means these rights cannot be legitimately taken away, though their exercise may be subject to reasonable limitations.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948, provides a comprehensive list of these rights, including the right to life, liberty, and security of person; freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; freedom from slavery and servitude; the right to a fair trial; freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; freedom of opinion and expression; and the right to education.

Positive rights require others to act in certain ways (e.g., the right to education necessitates the provision of educational resources), while negative rights require others to refrain from certain actions (e.g., the right to freedom of speech necessitates that others not prevent its exercise).

Types of Rights and Their Philosophical Underpinnings

Rights can be categorized into natural, legal, and moral rights. Natural rights are inherent and inalienable, grounded in the belief in human dignity and often considered pre-political. Their existence is independent of any legal or societal system. Philosophers like John Locke argued for natural rights such as life, liberty, and property. Legal rights are granted by law and are subject to the specific provisions of a legal system.

They are created and enforced by the state. Moral rights stem from ethical principles and societal norms. These are not necessarily codified in law but are considered morally justifiable claims. Defining and enforcing natural rights presents challenges because there’s no universally agreed-upon mechanism for their enforcement outside of the development of legal and moral frameworks. Disagreements about the content and scope of natural rights frequently arise.

Comparison with Other Ethical Frameworks

Rights-based ethics differs from other frameworks. Utilitarianism prioritizes maximizing overall happiness, potentially sacrificing individual rights for the greater good. Deontology emphasizes duty and adherence to moral rules, regardless of consequences. Virtue ethics focuses on cultivating virtuous character traits. Conflicts can arise.

For example, a utilitarian approach might justify violating someone’s right to privacy to prevent a greater harm, while a deontological approach might insist on upholding the right regardless of the consequences. A virtue ethicist might focus on the character of the decision-maker, prioritizing honesty even if it violates a legal right. Imagine a scenario where whistleblowing reveals crucial information, violating confidentiality (a right), but preventing significant harm (utilitarian concern) and upholding a moral duty to truthfulness (deontological concern).

Types of Rights: Origins and Limitations

| Type of Right | Origin | Limitations | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Right (e.g., Right to Life) | Inherent human dignity | May be limited in extreme circumstances (e.g., self-defense) | The right to not be killed unjustly. |

| Legal Right (e.g., Right to Vote) | Statutory law or constitutional provision | Subject to legal restrictions (e.g., age, citizenship) | The right to vote in national elections. |

| Moral Right (e.g., Right to Privacy) | Ethical principles and societal norms | Can be overridden by competing moral considerations (e.g., public safety) | The right to have personal information protected. |

| Positive Right (e.g., Right to Education) | International human rights law and national constitutions | Resource constraints, unequal access | The right to free and compulsory primary education. |

| Negative Right (e.g., Right to Freedom of Speech) | International human rights law and national constitutions | Limitations for incitement to violence or defamation | The right to express one’s views without censorship. |

Case Study: Conflict of Rights

The case of Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing activities presents a conflict between national security and the right to freedom of information. Snowden leaked classified information about mass surveillance programs, exposing potential violations of privacy rights. While his actions could be seen as a violation of his duty of confidentiality (a legal and moral right), they also raised concerns about the government’s overreach and the public’s right to know (a moral and potentially legal right).

Analyzing this through different frameworks reveals complex considerations. Utilitarianism might weigh the benefits of transparency against the potential harm to national security. Deontology would focus on the duties involved, and virtue ethics would examine Snowden’s character and motivations. Resolving this conflict requires careful balancing of competing values.

International Human Rights Law and Its Role

International human rights law, exemplified by the UDHR and subsequent treaties, aims to establish universal standards for human rights protection. These instruments provide a framework for national legislation and international cooperation. Enforcement mechanisms include international courts, human rights monitoring bodies, and diplomatic pressure. However, implementation faces challenges due to state sovereignty, differing legal systems, and resource constraints.

Some states may prioritize national interests over human rights obligations.

Effectiveness of Rights-Based Approaches

Rights-based approaches have achieved notable successes in promoting equality, justice, and human dignity, contributing to positive changes in areas like women’s rights and anti-discrimination laws. However, limitations exist. A sole focus on rights can neglect other crucial factors like economic development or cultural contexts. For example, while the right to education is universally recognized, achieving equitable access requires addressing issues of poverty and inequality.

Improving effectiveness requires integrating rights-based approaches with other strategies, such as development initiatives and community engagement.

Social Contract Theory

Social contract theory offers a compelling framework for understanding the relationship between individuals and the state. It posits that individuals voluntarily surrender certain rights and freedoms in exchange for the protection and benefits provided by a governing authority. This agreement, often implicit rather than explicitly written, forms the basis of a just and ordered society. Exploring this theory allows us to examine the foundations of political legitimacy and the responsibilities we have to both ourselves and our communities.Social contract theory’s core principles center on the idea of a reciprocal agreement.

Individuals agree to abide by certain rules and laws, while the state, in turn, agrees to protect their rights and provide essential services. This exchange necessitates cooperation, as the success of the social contract relies on the collective commitment of its members to uphold their end of the bargain. Without this cooperation, the system would crumble, leading to chaos and instability.

Understanding the nuances of this agreement and its implications is crucial for navigating the complexities of social and political life.

Core Principles of Social Contract Theory

The fundamental principles underlying social contract theory involve a hypothetical agreement between individuals and the state. This agreement Artikels the rights and responsibilities of each party, establishing the framework for a functioning society. Central to this agreement is the concept of mutual benefit, where individuals relinquish some autonomy for the collective good, ensuring protection and stability. The theory also emphasizes the importance of consent, suggesting that the legitimacy of the state rests on the willingness of individuals to participate in the social contract.

Finally, the concept of justice plays a significant role, as the contract aims to create a fair and equitable society where the rights and needs of all members are considered.

The Role of Agreement and Cooperation

Agreement and cooperation are indispensable to the success of any social contract. The initial agreement establishes the foundational rules and norms of society, defining acceptable behavior and the limits of individual autonomy. Cooperation, however, is the ongoing process by which individuals uphold their end of the agreement, contributing to the stability and well-being of the community. Without cooperation, the system of rules and laws becomes ineffective, leading to social breakdown.

This interplay between initial agreement and sustained cooperation underscores the dynamic and evolving nature of the social contract.

Different Versions of Social Contract Theory

Several prominent thinkers have offered varying interpretations of social contract theory. Thomas Hobbes, writing in the context of the English Civil War, envisioned a state of nature characterized by constant conflict and a relentless struggle for survival. He argued that individuals would rationally choose to submit to an absolute sovereign to escape this brutal state, even if it meant sacrificing some individual liberty.

John Locke, in contrast, presented a more optimistic view, suggesting that individuals possess natural rights, including the right to life, liberty, and property, that cannot be legitimately infringed upon by the state. He believed the social contract was primarily designed to protect these rights. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, meanwhile, emphasized the concept of the “general will,” arguing that individuals should submit to the collective will of the community, even if it conflicts with their individual desires.

These differing perspectives highlight the diverse ways in which the social contract can be conceived and implemented.

Limitations of Social Contract Theory

Despite its influence, social contract theory faces several limitations. One significant challenge is the difficulty of determining the exact terms of the agreement, especially given the diverse perspectives and interests within any society. The theory often struggles to account for the needs and interests of marginalized groups who may not have had a voice in the creation of the social contract.

Furthermore, the theory’s reliance on individual rationality and consent can be problematic, as not all individuals are capable of rational decision-making, and consent may be coerced or otherwise not truly voluntary. Finally, the theory can struggle to address situations where the social contract itself is unjust or oppressive, raising questions about how such a contract can be legitimately challenged or reformed.

Feminist Ethics

Feminist ethics is not a single, unified theory but rather a diverse collection of perspectives united by a common goal: to critically examine and challenge traditional ethical frameworks that often perpetuate gender inequality and injustice. It seeks to understand and address ethical issues from the standpoint of women and other marginalized groups, offering alternative approaches that prioritize care, relationality, and social justice.

This exploration will delve into the core tenets of feminist ethics, its critiques of traditional theories, its applications to pressing social issues, and its intersections with other ethical frameworks.

Core Tenets of Feminist Ethics

Feminist ethics encompasses several interconnected approaches, each offering unique insights into ethical decision-making. These approaches are not mutually exclusive; rather, they often complement and inform one another, creating a rich and nuanced ethical framework.

Care Ethics within Feminist Thought

Care ethics, central to many feminist perspectives, emphasizes the importance of relationships, empathy, and responsibility in ethical decision-making. Unlike deontological approaches, which focus on rules and duties, or consequentialist approaches, which prioritize outcomes, care ethics prioritizes the well-being of those with whom we are in relationship. It recognizes the importance of context and the unique needs of individuals within specific relationships.

For example, a mother’s decision to prioritize her child’s needs over her own career aspirations is ethically justifiable within a care ethics framework, even if it might not maximize overall happiness (utilitarianism) or perfectly adhere to a universal moral rule (Kantianism). This approach challenges the traditional emphasis on impartiality and abstract reasoning, instead valuing emotional responsiveness and contextual understanding.

| Feature | Care Ethics | Utilitarianism | Kantianism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Relationships, empathy, responsibility | Maximizing overall happiness/well-being | Duty, universalizability, categorical imperative |

| Decision-Making | Contextual, relational, responsive to needs | Calculation of consequences | Application of moral rules |

| Key Concepts | Care, empathy, vulnerability, interdependence | Utility, happiness, consequences | Duty, rationality, autonomy |

Feminist Virtue Ethics

Feminist virtue ethics distinguishes itself from traditional virtue ethics by challenging the historically male-dominated conception of virtues. Traditional virtue ethics often emphasized virtues like courage and justice in abstract, gender-neutral terms. Feminist virtue ethics, however, highlights virtues that have been historically undervalued or associated with femininity, such as empathy, compassion, and nurturing. Three key virtues emphasized are: (1) Empathy: the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, crucial for recognizing and responding to injustice; (2) Relationality: valuing interconnectedness and interdependence, acknowledging the impact of our actions on others; (3) Courage: the strength to challenge oppressive systems and advocate for social justice, redefined to encompass the courage to express vulnerability and seek support.

For instance, a woman challenging gender pay inequality in her workplace demonstrates courage, relationality (by building alliances with colleagues), and empathy (by understanding the struggles of other women facing similar situations).

Relational Autonomy

Relational autonomy, a key concept in feminist ethics, challenges the traditional understanding of autonomy as individualistic and self-sufficient. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of social relationships and interdependence in shaping our choices and actions. Traditional notions of autonomy often ignore the power dynamics and social constraints that limit the choices available to women and other marginalized groups. Relational autonomy recognizes that genuine autonomy requires supportive relationships and the absence of coercion or undue influence.

This perspective has significant implications for understanding consent and agency, particularly in situations involving intimate relationships or power imbalances. For example, a woman’s ability to give informed consent to sexual activity is not solely determined by her individual capacity to understand the risks but also by the social context and power dynamics within the relationship.

Challenging Traditional Ethical Theories

Feminist ethics provides a powerful critique of several assumptions underlying traditional ethical theories, revealing their limitations in addressing gender inequality.

Critique of Universalism

Feminist ethics challenges the universality of traditional moral principles, arguing that ethical considerations must be context-specific and situated. Universal moral principles, often developed from a male-dominated perspective, may fail to address the unique experiences and needs of women. For instance, a universal principle emphasizing impartiality might ignore the ethical imperative to prioritize the needs of women experiencing domestic violence, given the power imbalance in such relationships.

Ethical theories, like utilitarianism or deontology, provide frameworks for moral decision-making. Understanding the difference between a theory and a hypothesis is crucial when evaluating these frameworks; to understand this better, check out this resource on which of the following distinguishes a theory from a hypothesis. Essentially, ethical theories are well-substantiated explanations of moral behavior, unlike fleeting hypotheses.

Critique of Impartiality

The ideal of impartiality, central to many traditional ethical theories, is criticized for ignoring the ethical importance of partiality towards marginalized groups. Feminist ethics argues that partiality towards those who have been historically disadvantaged is not only justifiable but morally necessary to address systemic injustice. For example, prioritizing the needs of women in access to reproductive healthcare is a justifiable instance of partiality, given the historical marginalization of women in this domain.

Critique of Abstract Reasoning

Feminist ethics critiques the reliance on abstract reasoning and detached moral judgment, advocating for embodied and relational approaches to ethical decision-making. Abstract reasoning, divorced from lived experience, often overlooks the complexities and nuances of gendered realities. For example, abstract discussions of justice might fail to address the unique challenges women face in accessing legal recourse for gender-based violence, due to systemic biases and lack of resources.

Addressing Issues of Gender Inequality

Feminist ethics offers valuable frameworks for understanding and addressing a range of gender inequality issues.

Reproductive Rights

Feminist ethics addresses the ethical dilemmas surrounding reproductive rights by emphasizing bodily autonomy and reproductive justice. It challenges the view that women’s bodies are public property, arguing that women have the right to control their own reproductive lives, including access to contraception, abortion, and prenatal care. Access to these services is not just a matter of individual choice but also a matter of social justice, as limitations disproportionately affect marginalized women.

Gender-Based Violence

Feminist ethics provides a framework for understanding and addressing gender-based violence, including domestic violence, sexual assault, and harassment. It challenges the normalization of such violence, emphasizing the importance of holding perpetrators accountable and providing support for survivors. The focus is on understanding the power dynamics that underpin such violence and addressing the systemic factors that contribute to its prevalence.

Workplace Discrimination, What are ethical theories

Feminist ethical principles can be used to analyze and challenge gender discrimination in the workplace, addressing issues like pay equity, promotion opportunities, and workplace harassment. For instance, the principle of equal pay for equal work, grounded in feminist ethics, directly challenges the gender pay gap and highlights the injustice of undervaluing women’s work.

Intersectionality and Other Ethical Frameworks

Feminist ethics increasingly recognizes the importance of intersectionality and its intersections with other ethical frameworks.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality, the interconnectedness of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, is crucial for feminist ethics. It recognizes that women’s experiences are shaped by multiple intersecting factors and that gender inequality cannot be understood in isolation from other forms of oppression. For example, a Black woman’s experience of gender inequality will differ significantly from a white woman’s due to the added layer of racial discrimination.

Environmental Ethics

The intersection of feminist ethics and environmental ethics highlights how environmental degradation disproportionately affects women and marginalized communities. Women are often disproportionately responsible for securing resources like water and fuel, making them particularly vulnerable to environmental damage. Furthermore, environmental justice movements often prioritize the needs of communities who have historically been marginalized and subjected to environmental hazards.

Bioethics

Feminist ethics offers a critical perspective on contemporary bioethical issues such as reproductive technologies, genetic engineering, and end-of-life care. For example, feminist bioethics examines the potential for reproductive technologies to reinforce gender inequalities or to create new forms of discrimination. It also critically assesses the impact of medical practices on women’s health and well-being.

Environmental Ethics

Environmental ethics explores the moral relationship between humans and the natural world. It grapples with questions of our responsibilities towards the environment and the ethical implications of our actions on ecosystems and other living beings. Understanding environmental ethics is crucial in navigating the complex challenges of sustainability and ecological preservation in an increasingly human-dominated world.

Core Principles of Environmental Ethics

Environmental ethics rests on several core principles, often intertwined and debated. A central tenet is the inherent value of nature, arguing that natural entities possess intrinsic worth beyond their usefulness to humans. This contrasts with anthropocentric views that prioritize human interests above all else. Another key principle involves recognizing the interconnectedness of all living things within ecosystems; damage to one part of the system can have cascading effects throughout.

Finally, the principle of sustainability emphasizes the need to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. These principles guide the development and application of various ethical frameworks within environmental discussions.

Ethical Obligations Towards the Environment

Humans have a wide range of ethical obligations towards the environment, stemming from the principles mentioned above. These obligations extend beyond simply avoiding direct harm, encompassing responsibilities for preventing pollution, conserving resources, protecting biodiversity, and mitigating climate change. This includes individual actions like reducing our carbon footprint and supporting sustainable practices, as well as collective efforts through policy and legislation to protect natural resources and ecosystems.

The extent of these obligations is often debated, but the core idea remains: our actions have consequences for the environment, and we have a moral responsibility to act in ways that minimize harm and promote ecological well-being.

Approaches to Environmental Ethics: Anthropocentrism and Biocentrism

Anthropocentrism, a human-centered approach, places human well-being at the forefront of ethical considerations. Environmental concerns are primarily viewed through the lens of their impact on humans, focusing on the benefits or harms to human health, economic prosperity, or quality of life. Conversely, biocentrism assigns intrinsic value to all living things, not just humans. This perspective emphasizes the moral consideration of all organisms and ecosystems, advocating for their protection regardless of their usefulness to humans.

While anthropocentrism might prioritize human needs, biocentrism promotes a broader, more holistic ethical framework that values the entire web of life. Ecocentrism, a related perspective, extends this further, valuing entire ecosystems and their processes as intrinsically valuable.

Hypothetical Environmental Dilemma: The Dam Project

Imagine a scenario where a proposed hydroelectric dam promises significant economic benefits for a region, creating jobs and providing clean energy. However, the dam’s construction would flood a pristine valley, displacing indigenous communities and destroying a unique ecosystem that harbors endangered species. This presents a classic environmental dilemma: weighing the economic advantages for the broader population against the ecological and social costs.

Different ethical frameworks would lead to different conclusions. An anthropocentric approach might prioritize the economic benefits, while a biocentric or ecocentric approach would likely emphasize the protection of the valley and its inhabitants, even at the cost of economic growth. The resolution of such dilemmas requires careful consideration of various ethical perspectives and the potential consequences of different courses of action.

Business Ethics

Navigating the complex world of business requires a strong ethical compass. Ethical considerations are no longer a peripheral concern but a fundamental aspect of sustainable success, impacting not only a company’s reputation but also its long-term viability. This section explores key ethical challenges faced by businesses, the role of corporate social responsibility, common ethical dilemmas, and strategies for fostering ethical behavior within organizations.

Ethical Challenges Faced by Businesses: Data Privacy in E-commerce

The digital age has revolutionized commerce, but it has also introduced significant ethical challenges related to data privacy. E-commerce businesses collect vast amounts of customer data, including personal information, browsing history, and purchasing patterns. The ethical challenge lies in balancing the legitimate business interests of utilizing this data for marketing, personalization, and improving services with the fundamental right of individuals to privacy and control over their personal information.

Violations can range from unauthorized data sharing with third parties to inadequate security measures leading to data breaches. The consequences can be severe, including hefty fines, reputational damage, loss of customer trust, and legal action. For example, the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where Facebook user data was improperly harvested and used for political advertising, resulted in significant fines and eroded public trust in the platform.

Another example is the Equifax data breach in 2017, which exposed the personal information of millions of consumers, leading to significant financial losses and reputational damage for the company.

Ethical Challenges Faced by Businesses: Outsourcing and Ethical Sourcing

Outsourcing manufacturing to countries with lower labor and environmental standards presents a significant ethical dilemma. While cost reduction is a key driver for businesses, the practice often raises concerns about exploitation of workers, unsafe working conditions, and environmental degradation. This tension highlights the conflict between maximizing profits and upholding ethical sourcing principles. Fair trade principles, which emphasize fair prices, safe working conditions, and environmental sustainability, offer a framework for ethical sourcing.

However, ensuring compliance with these principles throughout complex global supply chains can be challenging. For example, the garment industry has faced repeated criticism for its reliance on sweatshops in developing countries, with workers often subjected to low wages, long hours, and unsafe working conditions. Companies are increasingly under pressure to demonstrate their commitment to ethical sourcing through transparency and accountability in their supply chains.

Ethical Challenges Faced by Businesses: Multinational Corporations in Different Contexts

Multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in developing countries face a unique set of ethical challenges compared to those operating solely within developed nations. These challenges often involve navigating differing legal and regulatory frameworks, cultural norms, and levels of corruption. Bribery and corruption are significant concerns, as MNCs may be tempted to engage in these practices to secure favorable business deals or circumvent regulations.

Ethical theories, like utilitarianism or deontology, guide moral decision-making. Understanding these frameworks helps us navigate complex situations, such as those presented by the fascinating concept of the “taxi cab theory,” which you can learn more about here: what is the taxi cab theory. Ultimately, applying ethical theories involves considering consequences and principles, making the taxi cab theory a great case study for ethical reflection.

Human rights issues, such as worker exploitation and environmental damage, are also more prevalent in developing countries, where regulatory oversight may be weaker. MNCs operating in developed nations face ethical challenges related to data privacy, environmental sustainability, and fair labor practices, but these challenges are often subject to stricter regulations and greater public scrutiny. The ethical standards and expectations placed on MNCs operating in developing countries often need to be carefully balanced against the local context and legal frameworks.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Business Ethics: Environmental Impact Mitigation

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) plays a crucial role in mitigating the environmental impact of businesses. Many companies are adopting sustainable practices to reduce their carbon footprint, conserve resources, and minimize waste. The following table showcases examples across different industries:

| Industry | Company | Specific Sustainable Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable Energy | NextEra Energy | Investing heavily in wind and solar energy projects, reducing reliance on fossil fuels. |

| Apparel | Patagonia | Using recycled materials, promoting fair labor practices, and advocating for environmental protection. |

| Food and Beverage | Unilever | Reducing water usage in its supply chain, sourcing sustainable palm oil, and reducing its carbon footprint. |

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Business Ethics: CSR Reporting Frameworks

Several CSR reporting frameworks aim to enhance transparency and accountability. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) provides a widely used framework for reporting on a company’s economic, environmental, and social performance. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) focuses on financially material sustainability issues relevant to investors. While both frameworks promote transparency, they differ in their scope and focus. GRI offers a broader range of indicators, while SASB focuses on issues directly impacting a company’s financial performance.

The strengths of GRI lie in its comprehensive coverage and global acceptance, while SASB’s strength lies in its focus on materiality for investors. Weaknesses of GRI include the potential for excessive reporting and lack of standardization, while SASB may be criticized for its narrow focus on financial materiality.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Business Ethics: CSR and Financial Performance

The relationship between CSR initiatives and a company’s financial performance is complex and not always straightforward. The “creating shared value” concept suggests that companies can improve their financial performance by addressing social and environmental issues. Empirical evidence supporting this claim is mixed, with some studies showing a positive correlation between CSR and financial performance, while others find no significant relationship or even a negative correlation in certain contexts.

The impact of CSR on financial performance can vary depending on factors such as the nature of the CSR initiatives, the industry, and the company’s overall business strategy. Further research is needed to fully understand this complex relationship.

Medical Ethics

Medical ethics provides a framework for navigating the complex moral considerations inherent in healthcare. It guides healthcare professionals in making decisions that respect patient autonomy, promote well-being, and uphold fairness within the healthcare system. Understanding these principles is crucial for ensuring ethical and responsible medical practice.

Key Principles of Medical Ethics

The four core principles – autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice – form the cornerstone of medical ethics. These principles often interact and sometimes conflict, requiring careful consideration and thoughtful deliberation in practice.

- Autonomy: Respecting a patient’s right to self-determination and their capacity to make informed decisions about their own healthcare. This includes providing patients with all necessary information to make choices, respecting their refusal of treatment, and ensuring confidentiality.

- Beneficence: Acting in the best interests of the patient. This involves actively promoting the patient’s well-being and striving to improve their health outcomes. It requires careful consideration of potential benefits and risks associated with any intervention.

- Non-maleficence: Avoiding actions that could cause harm to the patient. This principle emphasizes the importance of minimizing risks and potential side effects of treatments while maximizing benefits. It underscores the responsibility to “do no harm.”

- Justice: Ensuring fairness and equity in the distribution of healthcare resources and ensuring that all patients receive equal access to quality care regardless of their background or socioeconomic status. This principle addresses issues of resource allocation and healthcare disparities.

Ethical Dilemmas in Medical Practice

Medical professionals frequently encounter situations where these principles clash, creating ethical dilemmas. These dilemmas often involve balancing competing values and making difficult choices with significant consequences.

- End-of-life care: Deciding whether to provide life-sustaining treatment, particularly when the patient is terminally ill and wishes to forgo treatment. This involves navigating the patient’s autonomy alongside the physician’s duty of beneficence.

- Resource allocation: Determining how to distribute limited healthcare resources fairly among patients with competing needs. This often involves difficult decisions regarding organ transplantation, access to expensive medications, and prioritization of patients in emergency situations.

- Informed consent: Ensuring patients fully understand the risks and benefits of a proposed treatment before consenting to it. This can be challenging when dealing with complex medical information or patients with limited cognitive capacity.

- Confidentiality breaches: Balancing the duty to maintain patient confidentiality with the obligation to report certain information to protect public safety (e.g., mandatory reporting of child abuse).

Examples of Ethical Decision-Making in Healthcare

Ethical decision-making in healthcare involves a systematic approach, often including consultation with colleagues, ethics committees, and consideration of relevant guidelines.

- A physician discussing treatment options with a patient, ensuring the patient understands the risks and benefits of each option before making a decision, thereby upholding the principle of autonomy.

- A hospital allocating scarce ventilators during a pandemic based on established criteria that prioritize patients with the highest chance of survival, demonstrating commitment to justice and beneficence.

- A nurse advocating for a patient’s right to refuse a blood transfusion based on their religious beliefs, respecting the patient’s autonomy even if it differs from medical recommendations.

Challenges of Applying Ethical Principles in Complex Medical Situations

Applying ethical principles in complex medical situations can be extremely challenging. The principles themselves may conflict, and the context of the situation may make it difficult to apply them consistently.

- Uncertainty and ambiguity: Medical situations often involve uncertainty about prognosis and treatment effectiveness, making it difficult to determine the best course of action from an ethical standpoint.

- Cultural and religious differences: Patients’ cultural and religious beliefs can significantly influence their healthcare preferences, potentially creating conflicts with standard medical practices.

- Technological advancements: New technologies raise new ethical dilemmas, such as those related to genetic testing, reproductive technologies, and artificial intelligence in healthcare.

- Emotional distress: Healthcare professionals themselves can experience emotional distress when faced with difficult ethical decisions, potentially affecting their judgment and decision-making.

Applied Ethics

Applied ethics takes the abstract principles of ethical theories and puts them into practice, grappling with real-world dilemmas. It’s about bridging the gap between philosophical ideals and the messy complexities of human life. This involves analyzing specific situations, identifying relevant ethical issues, and then applying ethical frameworks to determine the most morally justifiable course of action.Ethical theories provide a valuable framework for navigating moral quandaries, but their application isn’t always straightforward.

The challenges arise from the inherent ambiguity of real-world situations, the potential conflict between different ethical principles, and the diversity of cultural and individual perspectives. Context matters significantly; a decision deemed ethical in one culture might be considered unethical in another. Furthermore, the practical application of theoretical principles often requires careful consideration of unintended consequences and the limitations of our knowledge.

Challenges of Applying Ethical Theories

Applying ethical theories to diverse contexts presents several significant challenges. Cultural relativism, for example, suggests that moral standards are culturally specific, making the application of universal ethical frameworks difficult. Conflicting ethical principles – such as individual autonomy versus the welfare of the community – can also create complex dilemmas requiring careful balancing. The lack of clear-cut answers and the need for nuanced judgment in many real-world situations further complicates the application process.

Finally, unforeseen consequences, which are often difficult to anticipate, can render even the most well-intentioned ethical decisions problematic.

Applied Ethics in Law

Legal systems often draw upon ethical frameworks to inform legislation and judicial decisions. For example, the concept of justice, a central theme in many ethical theories, guides the development of fair legal processes and equitable outcomes. Debates about capital punishment, for instance, frequently involve consequentialist arguments about deterrence versus deontological concerns about the inherent wrongness of taking a human life.

Similarly, discussions around legal rights often engage with rights-based ethical theories, while considerations of fairness and equity draw upon principles from other ethical perspectives.

Applied Ethics in Politics

Political decision-making frequently involves ethical considerations. The allocation of resources, the design of public policies, and the conduct of international relations all raise complex ethical questions. For example, utilitarianism might be used to justify policies that maximize overall well-being, while deontology might emphasize the importance of upholding human rights regardless of the potential consequences. Political debates about issues such as healthcare access, environmental protection, and national security often reflect these differing ethical perspectives.

The challenge lies in finding a balance between competing values and achieving ethically sound solutions that are also politically feasible.

Applied Ethics in Technology

Rapid technological advancements present novel ethical challenges. The development and use of artificial intelligence, for example, raise questions about accountability, bias, and the potential displacement of human workers. Ethical frameworks can help guide the development of responsible AI systems, ensuring fairness, transparency, and respect for human dignity. Similarly, issues related to data privacy, genetic engineering, and autonomous weapons systems require careful ethical consideration, demanding the application of relevant ethical theories to navigate the complexities of these emerging technologies.

The goal is to harness the benefits of technology while mitigating potential harms.

Ethical Frameworks in Policy-Making

Ethical frameworks play a crucial role in policy-making by providing a structured approach to evaluating the moral implications of policy decisions. They offer a mechanism for identifying potential ethical conflicts, considering the perspectives of different stakeholders, and justifying policy choices. For instance, a cost-benefit analysis, often associated with consequentialism, might be used to assess the overall impact of a policy on society.

Alternatively, a rights-based approach might prioritize the protection of fundamental human rights, even if doing so entails some economic costs. By explicitly incorporating ethical considerations into the policy-making process, policymakers can strive to create policies that are both effective and morally justifiable.

Meta-ethics

Meta-ethics delves into the fundamental nature of moral judgments, exploring their properties, relationships with other concepts like truth and reason, and the various philosophical positions concerning their existence and justification. Understanding meta-ethics provides a crucial framework for analyzing and evaluating ethical theories and making informed ethical decisions.

The Nature of Moral Judgments

This section examines the key characteristics of moral judgments and categorizes their different forms. Understanding these properties helps clarify the unique role moral judgments play in our lives and in shaping our actions.

Properties of Moral Judgments

The following table Artikels key properties of moral judgments, illustrating each with examples and counter-examples to highlight the distinctions.

| Property | Definition | Example | Counter-Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescriptivity | The capacity to guide or motivate action. | “Lying is wrong, therefore you should not lie.” | “The sky is blue.” |

| Universality | The applicability of a moral judgment to all relevant individuals/situations. | “Killing is wrong” applies to all instances of unjustified killing. | “This cake is delicious” (subjective preference). |

| Overridingness | The priority of moral considerations over other factors. | Moral obligations often outweigh personal desires or convenience. For example, choosing to help a stranger in need, even if it causes personal inconvenience. | Choosing a comfortable but unethical job over a challenging ethical one. |

| Objectivity | The extent to which a moral judgment is independent of personal opinion. | “Torture is wrong” (ideally, independent of personal feelings). | “Pineapple on pizza is disgusting” (subjective opinion). |

Types of Moral Judgments

Moral judgments can be categorized based on their target. This categorization aids in a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of moral evaluation.

- Judgments about actions: “Stealing is wrong,” “Donating to charity is good,” “Lying to a friend is morally questionable.”

- Judgments about character: “She is a kind person,” “He is dishonest,” “They are compassionate and empathetic.”

- Judgments about motives: “Acting out of self-interest is morally problematic,” “Altruistic motives are commendable,” “Their intentions were good, despite the negative outcome.”

- Judgments about consequences: “The consequences of this action were devastating,” “The outcome was beneficial for everyone involved,” “This policy led to unforeseen negative consequences.”

Morality and Other Concepts

This section explores the intricate relationships between morality and truth, reason, and emotion, acknowledging their interwoven influence on moral judgment.

Morality and Truth

The relationship between moral judgments and truth is a central debate in meta-ethics. Moral realism asserts that moral statements can be true or false, mirroring factual statements. Conversely, moral anti-realism denies the existence of objective moral truths. Different meta-ethical theories offer varying perspectives on this relationship. For example, ethical naturalism attempts to ground moral truths in natural facts, while error theory argues that all moral statements are false.

Morality and Reason

The role of reason in moral judgment is a complex issue. Some argue that moral judgments are fundamentally rational, based on logical principles and evidence. Others emphasize the role of emotions and intuition, suggesting that reason plays a secondary role, or that it is entirely subservient to emotions in moral decision-making. The debate hinges on whether moral reasoning can be objectively evaluated or if it’s ultimately a matter of subjective preference or emotional response.

Morality and Emotion

Emotions significantly influence moral judgments, sometimes leading to biases and distortions. While empathy and compassion can motivate prosocial behavior, anger and fear can lead to biased and unjust judgments. Understanding the interplay between emotion and reason in moral decision-making is crucial for mitigating the potential negative impact of emotional biases. For instance, fear can lead to discriminatory actions against certain groups, while empathy can drive individuals to act altruistically, even at personal cost.

Meta-Ethical Positions

This section Artikels and compares prominent meta-ethical positions, highlighting their differing views on the nature of morality.

Moral Realism vs. Moral Anti-Realism

Moral realism posits the existence of objective moral facts independent of human opinion. Ethical naturalism, for example, seeks to define moral properties in terms of natural properties, such as pleasure or well-being. In contrast, moral anti-realism denies the existence of such objective facts. Error theory, for instance, argues that all moral statements are false because there are no moral facts to make them true.

Emotivism suggests that moral statements are merely expressions of emotion, lacking truth-value altogether.

Comparative Analysis Table

The following table summarizes key differences between four meta-ethical positions: Moral Realism (Ethical Naturalism), Moral Realism (Moral Intuitionism), Moral Anti-Realism (Emotivism), and Moral Anti-Realism (Error Theory).

| Position | Nature of Moral Judgments | Source of Moral Knowledge | Status of Moral Truth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Naturalism (Moral Realism) | Descriptive statements about natural properties | Empirical observation and scientific inquiry | Objective and verifiable |

| Moral Intuitionism (Moral Realism) | Intuitive grasp of self-evident moral truths | Intuition and reason | Objective and self-evident |

| Emotivism (Moral Anti-Realism) | Expressions of emotion or attitude | Subjective feelings and preferences | Not truth-apt (no truth value) |

| Error Theory (Moral Anti-Realism) | False beliefs about objective moral facts | Cognitive processes that generate false beliefs | False |

Implications for Ethical Decision-Making

This section explores the practical implications of different meta-ethical positions on ethical decision-making.

Case Study Analysis: The Trolley Problem

The trolley problem, a classic thought experiment, illustrates how different meta-ethical frameworks lead to varying resolutions. From a consequentialist perspective (a form of moral realism), one might prioritize minimizing harm, potentially sacrificing one life to save many. An emotivist, however, might focus on the emotional distress involved in making such a decision, rather than seeking an objectively “correct” answer.

Practical Implications

Adopting a specific meta-ethical position influences ethical decision-making across various contexts. Moral realism might promote a sense of objective moral obligation, potentially leading to greater consistency in ethical behavior. Moral anti-realism, on the other hand, might emphasize the importance of individual values and perspectives, allowing for greater flexibility in ethical decision-making, but potentially at the cost of a shared moral framework.

The choice of meta-ethical framework, therefore, has significant practical implications for personal, professional, and public life.

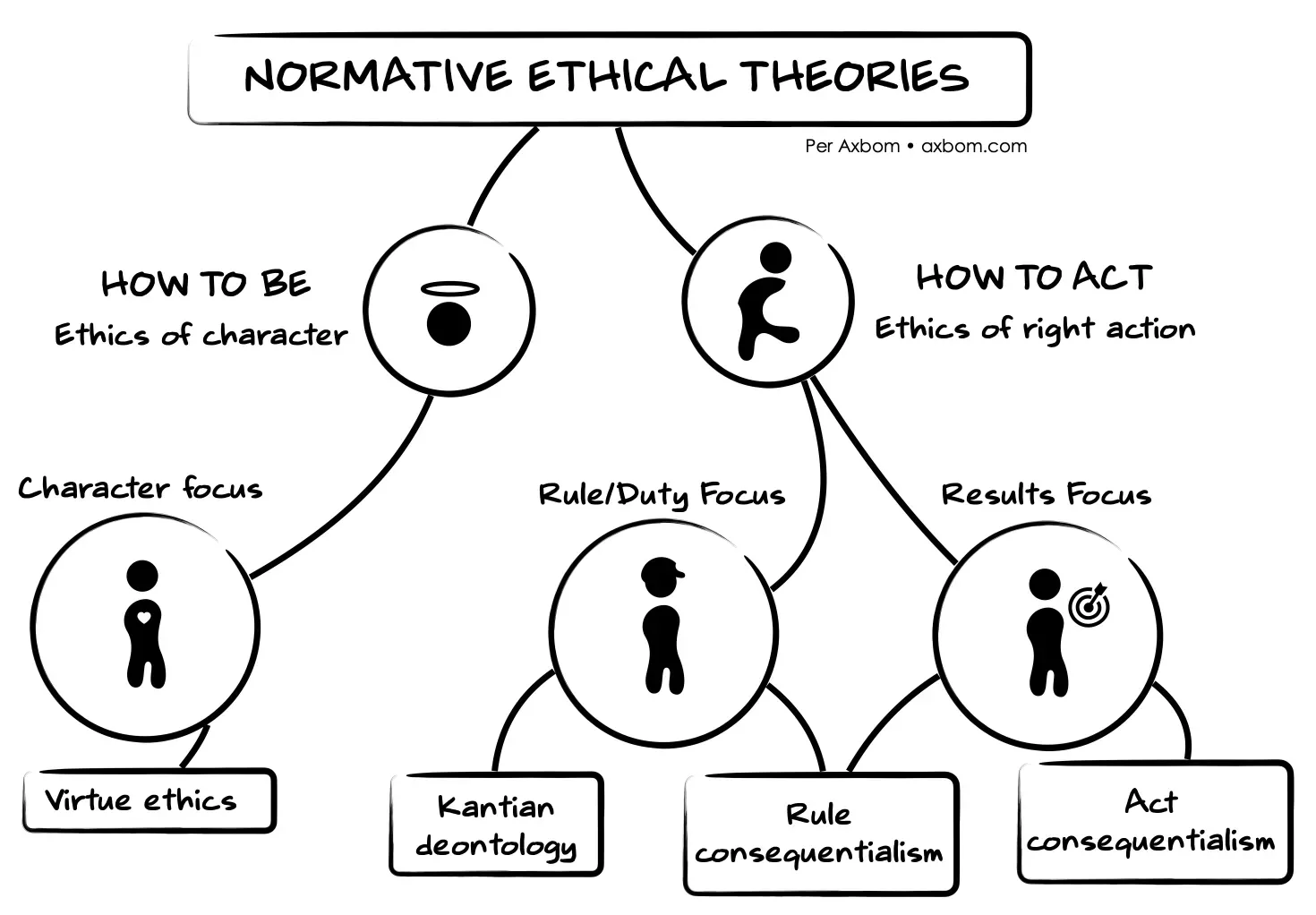

Normative Ethics

Normative ethics delves into the “shoulds” and “oughts” of morality, focusing on establishing principles and guidelines for determining right and wrong actions. Unlike descriptive ethics, which simply observes and describes moral beliefs and behaviors, normative ethics aims to prescribe moral actions and justify moral judgments. It seeks to provide a framework for making ethical decisions and resolving moral dilemmas.

Nature of Normative Ethical Theories

Normative ethical theories offer frameworks for determining moral actions and justifying moral judgments. They differ from descriptive ethics, which simply describes existing moral beliefs, by actively prescribing what ought to be done. Three key characteristics distinguish normative ethical theories: (1) they are prescriptive, offering guidance on how to act; (2) they are systematic, providing a coherent set of principles; and (3) they are justificatory, attempting to rationally defend their moral claims.

“Moral obligation,” within this framework, refers to a duty or responsibility to act in a specific way, often stemming from a principle or rule. For example, a consequentialist might feel morally obligated to save the most lives in a given situation (a utilitarian obligation), while a deontologist might feel obligated to tell the truth regardless of the consequences (a Kantian obligation).

These obligations represent differing approaches to moral decision-making.

Different Approaches to Normative Ethics: Consequentialism

Consequentialism judges the morality of an action solely based on its consequences. Utilitarianism, a prominent consequentialist theory, posits that the best action is the one that maximizes overall happiness or well-being. Act utilitarianism assesses each action individually, while rule utilitarianism focuses on establishing general rules that, if followed, tend to maximize overall happiness. In the trolley problem, an act utilitarian might choose to pull the lever to save the greater number of lives, even if it means sacrificing one person.

A rule utilitarian, however, might refuse to pull the lever, adhering to a rule against actively causing harm, even if it leads to a less optimal outcome in this specific instance. Ethical egoism, in contrast, asserts that the morally right action is the one that best serves the individual’s self-interest. A real-world example could be a business prioritizing profit maximization above all else, even if it means harming the environment or exploiting workers.

Consequentialist theories face challenges in accurately predicting consequences and objectively measuring overall well-being.

Different Approaches to Normative Ethics: Deontology

Kantian deontology emphasizes moral duties and rules, independent of consequences. The categorical imperative, central to Kantian ethics, dictates that one should only act according to principles that could be universally applied without contradiction. Two formulations are: (1) The Formula of Universal Law: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law; and (2) The Formula of Humanity: Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.

For example, lying is wrong according to the Formula of Universal Law because if everyone lied, trust would collapse, making lying impossible. The Formula of Humanity forbids using people merely as tools; for example, exploiting workers for profit is morally wrong. “Duty,” in Kantian deontology, is a strict obligation to adhere to moral rules, unlike the more flexible “obligation” in consequentialist theories, which is contingent on maximizing good.