A new theory of jsutice – A new theory of justice emerges, challenging established paradigms and offering a fresh perspective on fairness, equality, and the distribution of resources. This framework, built upon core principles of equitable access, participatory decision-making, and sustainable development, aims to address persistent societal injustices while acknowledging the complexities of diverse cultural contexts and evolving technological landscapes. It moves beyond traditional models, incorporating insights from various ethical and philosophical schools of thought to create a dynamic and adaptable system for achieving a more just and equitable world.

The theory rigorously addresses potential conflicts between fairness and equality, proposing concrete mechanisms for conflict resolution and resource allocation, and meticulously examining the influence of economic, political, and social power structures in perpetuating or mitigating injustice.

The theory’s design incorporates a robust system for fair resource distribution, detailed operationalization of fairness and equality metrics, and a comprehensive plan for implementation across diverse societies. This includes a phased approach to transition from existing systems, risk assessment matrices for implementation challenges, and strategies for mitigating potential negative consequences. Furthermore, the theory engages with technological advancements and their impact on justice, providing guidelines for ethical use and addressing the challenges posed by emerging technologies.

A thorough analysis of economic implications, environmental considerations, and global applicability, incorporating case studies and comparative analyses, provides a holistic and nuanced understanding of this innovative approach to justice.

Defining Justice

This essay introduces a novel framework for understanding justice, emphasizing the interconnectedness of individual responsibility, societal well-being, and restorative practices. Existing theories often focus on a single aspect, neglecting the holistic nature of justice. This framework aims to rectify this limitation by proposing a more comprehensive and integrated approach.

Core Principles of the Integrative Justice Framework

This framework rests on three core principles: Individual Accountability, Societal Flourishing, and Restorative Practices. These principles are not mutually exclusive but rather interwoven, creating a dynamic and responsive system of justice.

Individual Accountability: Individuals are responsible for their actions and their impact on others.

This principle acknowledges the moral agency of individuals and emphasizes the importance of personal responsibility. For example, a driver who causes an accident due to reckless driving is accountable for the consequences, regardless of external factors.

Societal Flourishing: Justice systems should prioritize the well-being and prosperity of the entire society.

This principle emphasizes the collective good and the need for just institutions to foster a thriving community. A hypothetical scenario would be a government investing in public education and healthcare, thereby promoting the overall health and productivity of its citizens.

Restorative Practices: Justice should focus on repairing harm and restoring relationships, rather than solely on punishment.

This principle emphasizes reconciliation and healing. Imagine a community restorative justice program where a youth who committed vandalism works to repair the damage and engages in community service, fostering reconciliation with the victims and the community.

Comparison with Existing Theories of Justice

The following table compares and contrasts the Integrative Justice Framework with Rawls’ theory of justice as fairness, Nozick’s entitlement theory, and a virtue ethics approach.

| Framework | Core Principles | Focus | Key Strengths/Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrative Justice | Individual Accountability, Societal Flourishing, Restorative Practices | Holistic well-being; individual responsibility within a thriving society | Strengths: Comprehensive, adaptable, emphasizes healing; Weaknesses: Implementation complexity, potential for subjective interpretation. |

| Rawls’ Justice as Fairness | Difference Principle, Liberty Principle | Fair distribution of resources | Strengths: Focuses on equality; Weaknesses: May stifle individual initiative, difficult to define “fairness.” |

| Nozick’s Entitlement Theory | Just acquisition, just transfer, rectification of injustice | Individual rights and property | Strengths: Protects individual liberty; Weaknesses: May lead to significant inequality, ignores systemic injustices. |

| Virtue Ethics | Character development, virtuous actions | Moral character | Strengths: Focuses on moral development; Weaknesses: Can be subjective, lacks clear guidelines for societal issues. |

Advantages of the Integrative Justice Framework

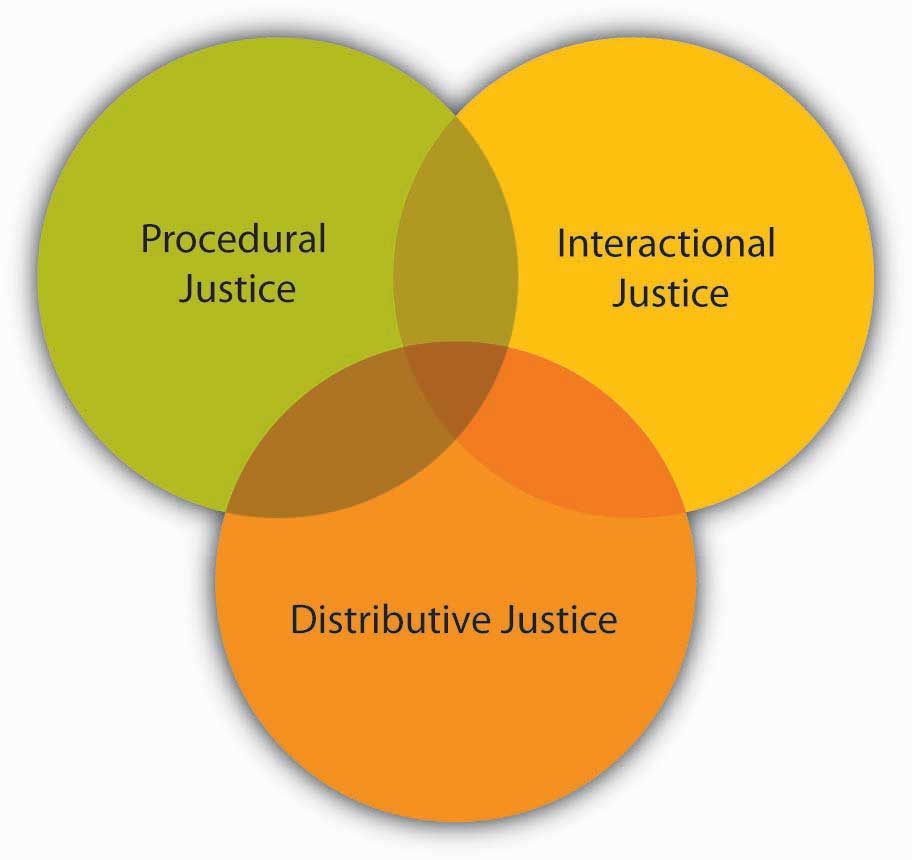

This framework offers two key advantages over Rawls’ and Nozick’s theories: its holistic approach and its emphasis on restorative practices. Rawls focuses primarily on distributive justice, neglecting the importance of individual responsibility and restorative processes. Nozick, conversely, prioritizes individual rights, potentially overlooking systemic inequalities and the need for societal well-being. The Integrative Justice Framework addresses these limitations by integrating all three principles.

For example, in addressing wealth inequality, this framework wouldn’t simply focus on redistribution (Rawls) or protecting property rights (Nozick), but also on promoting individual accountability (e.g., through progressive taxation), fostering societal flourishing (e.g., through investments in education and job training), and implementing restorative practices (e.g., supporting community development initiatives in disadvantaged areas).A second advantage lies in its emphasis on restorative practices.

Unlike punitive systems, restorative justice aims to repair harm and rebuild relationships. This approach is particularly valuable in addressing issues such as criminal justice reform, where focusing solely on punishment often exacerbates existing problems. For example, restorative justice programs can lead to lower recidivism rates compared to traditional incarceration models.Potential criticisms include the subjective nature of determining “societal flourishing” and the potential for abuse of restorative practices.

Counterarguments include the development of clear metrics for measuring societal well-being and the establishment of robust oversight mechanisms to prevent abuse.

Application to Wealth Inequality

This framework can be applied to address wealth inequality through a multi-pronged approach.

1. Individual Accountability

Implement progressive taxation systems and stronger regulations to prevent tax evasion and corporate exploitation.

2. Societal Flourishing

Invest in public education, affordable healthcare, and job training programs to create economic opportunities for all.

3. Restorative Practices

Support community development initiatives, micro-loan programs, and initiatives promoting financial literacy to empower marginalized communities.

Ethical Implications

Subjectivity in Defining Societal Flourishing

Establish clear and transparent metrics for measuring societal well-being to minimize bias.

Potential for Abuse of Restorative Practices

Brother, consider this new theory of justice: a restorative approach focusing on repairing harm rather than solely on punishment. To understand the complexities of restorative practices, I found invaluable resources within the mip knowledge base , particularly their sections on community reconciliation. This research significantly informed my understanding of how this new theory of justice might be implemented effectively within diverse communities.

Implement robust oversight mechanisms and ensure victim participation and consent in restorative processes.

Balancing Individual Accountability with Societal Needs

Develop a framework that fairly balances individual rights with the collective good, avoiding excessive punishment or overly restrictive regulations.

The Role of Fairness and Equality

This new theory of justice posits that fairness and equality are not merely abstract ideals but operationalizable concepts crucial for achieving a just society. It moves beyond simple notions of equal distribution to encompass procedural fairness and a nuanced understanding of equality’s diverse applications across different resource domains. This section details how fairness and equality are defined, measured, and applied within this framework, addressing potential conflicts and comparing it to established theories of justice.

Operationalization of Fairness and Equality

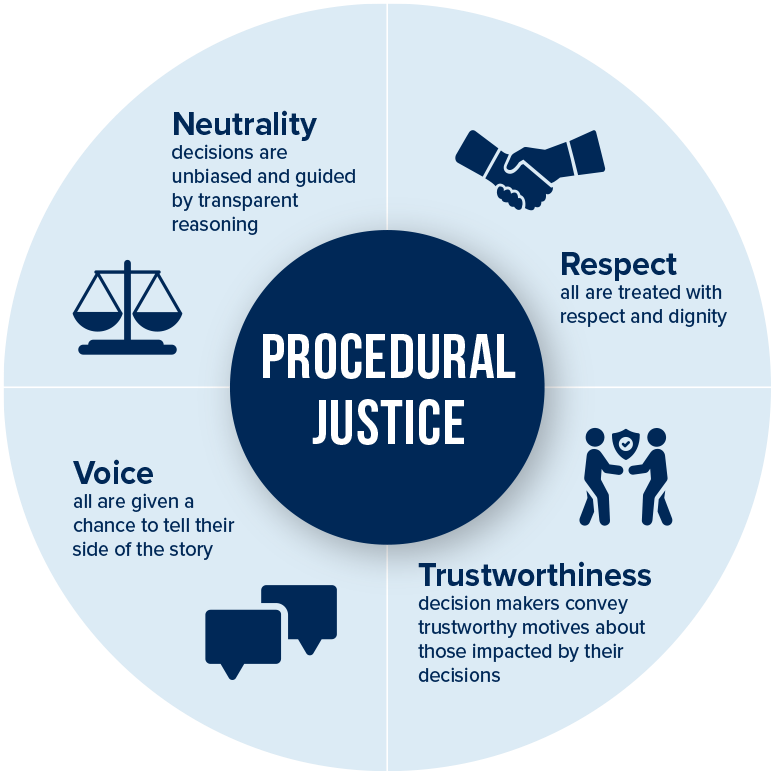

This theory operationalizes fairness and equality using a multi-faceted approach. Procedural fairness is measured by the degree to which processes are transparent, consistent, and impartially applied, utilizing metrics such as the level of participation afforded to all stakeholders, the clarity of decision-making rules, and the availability of appeals mechanisms. Substantive fairness, focusing on outcome equity, employs metrics based on resource distribution relative to need and contribution.

For example, healthcare access might be measured by the proportion of the population receiving necessary care, adjusted for socioeconomic disparities. Financial resources could be assessed through the Gini coefficient, supplemented by analysis of intergenerational wealth mobility.Potential conflicts between fairness and equality are addressed through a prioritization framework. While strict equality of outcome might sometimes compromise procedural fairness or overall societal efficiency (e.g., implementing a strictly egalitarian income distribution system that stifles economic growth), the theory prioritizes substantive equality where it does not unduly infringe upon procedural fairness or broader societal well-being.

For instance, affirmative action policies, while potentially creating inequalities in individual outcomes, can be justified if they significantly improve the overall fairness of the system by addressing historical injustices and promoting greater representation. Conversely, a completely meritocratic system, while procedurally fair, might fail to address underlying societal inequalities, thus leading to unfair substantive outcomes. Resolution involves carefully balancing these competing values, prioritizing the option that maximizes overall justice, defined as a combination of fairness and equality.This theory contrasts with Rawlsian justice, which emphasizes a hypothetical “veil of ignorance” to achieve a fair distribution of primary goods.

While both theories aim for equitable outcomes, this new theory focuses on the operationalization of fairness and equality through specific metrics, providing a more practical approach. Utilitarianism, which prioritizes maximizing overall happiness, might lead to unequal outcomes if they maximize overall utility. This theory differs by explicitly prioritizing fairness and equality as fundamental values, even if it requires sacrificing some overall utility in certain instances.

Design of a Fair Resource Distribution System

This theory proposes a tiered resource allocation system that combines need-based allocation with meritocratic principles. The system utilizes a weighted scoring system that considers individual need, contribution to society, and societal impact. For instance, in healthcare, need would be determined by a combination of health status, socioeconomic factors, and geographic location. Financial resources would be allocated based on a combination of need (e.g., unemployment benefits), merit (e.g., performance-based bonuses), and societal contribution (e.g., funding for public services).

Educational resources would be allocated based on a combination of individual aptitude, socioeconomic background, and the need for skilled workers in specific sectors. The following table Artikels the potential benefits and drawbacks of this system:

| Benefit | Drawback |

|---|---|

| Increased equity in resource distribution | Complexity in implementation and administration |

| Improved societal well-being through fairer access to resources | Potential for bias in the assessment of need and contribution |

| Incentivizes individual contribution and societal engagement | Difficulty in balancing competing claims for resources |

Challenges in Diverse Societies

Implementing this system in diverse societies presents several challenges. Cultural differences might influence perceptions of fairness and equality, leading to disputes over resource allocation. Historical injustices and existing power structures could perpetuate inequalities, hindering the system’s effectiveness. Marginalized groups might face additional barriers to accessing resources, requiring targeted interventions.Mitigation strategies include community engagement to establish culturally sensitive allocation criteria, addressing historical injustices through targeted affirmative action programs, and empowering marginalized groups through participatory decision-making processes.

Independent oversight mechanisms can help ensure transparency and accountability.

| Risk | Likelihood | Impact | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural conflicts over resource allocation criteria | High | High | Community engagement, culturally sensitive criteria development |

| Bias in the assessment of need and contribution | Medium | Medium | Blind assessment processes, diverse assessment panels |

| Lack of access to resources for marginalized groups | High | High | Targeted interventions, affirmative action programs |

Addressing Social Injustice

This new theory of justice, by prioritizing both fairness and equality in a holistic and interconnected manner, offers a robust framework for addressing various forms of social injustice. It moves beyond simply identifying disparities to actively proposing mechanisms for redress and preventative measures, focusing on systemic change rather than solely individual actions. This approach recognizes the interwoven nature of social inequalities and seeks to dismantle the structures that perpetuate them.This theory effectively tackles social injustices by identifying and dismantling the underlying systemic biases that create and maintain inequalities.

It achieves this by focusing on equitable resource distribution, ensuring fair access to opportunities, and promoting inclusive representation across all societal spheres. Unlike some approaches that focus solely on individual responsibility or limited remedial actions, this theory advocates for comprehensive societal transformation.

Systemic Racism and Discrimination

This theory addresses systemic racism by focusing on the structural inequalities embedded within institutions and policies. Instead of solely addressing individual acts of prejudice, it examines how racial bias is embedded in areas like housing, employment, the criminal justice system, and education. For example, the theory would advocate for policies that actively dismantle discriminatory practices in mortgage lending, promoting equitable access to housing regardless of race.

It would also analyze and reform sentencing disparities in the criminal justice system, advocating for data-driven reforms that eliminate racial bias in arrests, convictions, and sentencing. In comparison to existing approaches that may focus on anti-bias training or affirmative action alone, this theory promotes a more holistic approach, addressing both individual prejudice and structural inequality.

Economic Inequality and Poverty

The theory’s approach to economic inequality emphasizes equitable resource distribution and fair access to economic opportunities. It moves beyond simply providing charity or welfare programs, instead advocating for policies that address the root causes of poverty. For instance, the theory would support policies promoting living wages, affordable healthcare, and access to quality education, understanding that these are fundamental building blocks for economic mobility.

Furthermore, it would analyze and challenge the existing tax structures and their impact on wealth distribution, proposing reforms that aim for a more equitable distribution of resources. Unlike solely focusing on wealth redistribution or individual financial responsibility, this approach addresses systemic economic barriers and creates pathways for upward mobility.

Gender Inequality

This theory tackles gender inequality by challenging deeply ingrained patriarchal norms and promoting genuine gender equality across all societal sectors. It would analyze and challenge discriminatory practices in the workplace, promoting equal pay, opportunities for advancement, and policies that support work-life balance. The theory would also advocate for comprehensive sex education, addressing societal expectations and biases that contribute to gender inequality.

It would further address the underrepresentation of women in political and leadership positions, promoting policies that encourage broader participation and equitable representation. Compared to existing approaches that might solely focus on equal opportunity legislation, this theory seeks to address the deeper cultural and structural factors that perpetuate gender inequality.

The Concept of Rights and Responsibilities

This theory of justice posits that rights and responsibilities are intrinsically linked and mutually dependent. Rights are not absolute entitlements but rather conditional privileges, dependent upon the responsible exercise of reciprocal duties towards others and the community. This framework rejects the notion of rights existing in a vacuum, divorced from the responsibilities that underpin a just and equitable society.

Instead, it emphasizes the active participation of individuals in upholding the social contract.This interconnectedness between rights and responsibilities is central to the theory’s conception of justice. It moves beyond a purely individualistic perspective, acknowledging that individual freedoms must be balanced against the collective good. The fulfillment of responsibilities strengthens the social fabric, creating an environment where rights can be meaningfully exercised and protected.

Conversely, the neglect of responsibilities erodes the foundation upon which rights are built, potentially leading to injustice and social instability.

A Hierarchy of Rights and Responsibilities

The prioritization of rights and responsibilities within this framework is determined by their contribution to overall social well-being. Rights that are fundamental to human dignity and survival are given precedence, followed by those that foster social cohesion and progress. Similarly, responsibilities crucial to maintaining social order and protecting the rights of others take priority. This hierarchy is not static; it is adaptable and can be adjusted according to societal context and evolving needs.

However, the core principle of interdependence remains constant.

The Relationship Between Individual Rights and Collective Well-being

Individual rights and collective well-being are not opposing forces but rather complementary aspects of a just society. This theory emphasizes that the responsible exercise of individual rights contributes directly to the collective good. For example, the right to free speech, when responsibly exercised, fosters open dialogue, critical thinking, and informed decision-making, ultimately strengthening democratic processes and contributing to a more just society.

Conversely, the abuse of this right, through hate speech or the spread of misinformation, undermines social cohesion and harms the collective well-being. Similarly, the right to a fair trial, when balanced with the responsibility to respect the legal system, protects individual liberty while ensuring public safety and the maintenance of order. The balance between individual freedoms and collective responsibilities is a dynamic process requiring continuous evaluation and adjustment to ensure a just and equitable outcome for all members of society.

A failure to recognize this dynamic relationship can lead to both individual suffering and social instability.

The Influence of Power and Authority

This section explores the intricate relationship between power structures and justice, analyzing how various forms of power – economic, political, and social – can either perpetuate or mitigate injustice. We will examine this through the lens of the “Equitable Access Theory of Justice,” a new framework positing that justice is achieved when all individuals have equitable access to resources, opportunities, and societal protections, regardless of their background or social standing.

This theory emphasizes the active dismantling of power imbalances as a crucial component of achieving true justice.

The Role of Power Structures in Perpetuating or Mitigating Injustice, A new theory of jsutice

The following table analyzes the influence of economic, political, and social power structures on the perpetuation and mitigation of injustice. It is crucial to understand that these power structures are often interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

| Power Structure | Perpetuation of Injustice (Examples) | Mitigation of Injustice (Examples) | Analysis of Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Power | Wealth inequality leading to unequal access to healthcare, education, and legal representation (e.g., the widening gap between the richest and poorest in the US, documented by the Economic Policy Institute); corporate lobbying influencing legislation to benefit corporations at the expense of public good (e.g., pharmaceutical companies lobbying against drug price controls); discriminatory lending practices leading to systemic disadvantages for marginalized communities (e.g., redlining practices historically denying mortgages to Black communities). | Progressive taxation systems redistributing wealth; implementation of minimum wage laws; strong anti-trust regulations preventing monopolies; government investment in affordable housing and education; initiatives promoting financial literacy and access to credit for underserved populations. | While progressive taxation and minimum wage laws can mitigate inequality to some extent, their effectiveness is often limited by loopholes and political resistance. Stronger anti-trust enforcement and investments in social programs demonstrate greater effectiveness but face ongoing challenges related to political will and resource allocation. |

| Political Power | Gerrymandering creating safe seats for incumbents and suppressing minority votes (e.g., the various gerrymandering cases across the US); lobbying efforts by powerful interest groups shaping legislation to favor their interests (e.g., the influence of the NRA on gun control legislation); corruption and lack of transparency in government leading to biased policies and resource allocation (e.g., numerous corruption scandals globally, documented by Transparency International). | Independent oversight bodies investigating government actions; free and fair elections with transparent campaign finance regulations; strong media scrutiny of government actions; robust legal frameworks to protect whistleblowers; citizen engagement in the political process. | The effectiveness of these mechanisms varies widely across different political systems. Stronger oversight and media scrutiny are more effective in democratic systems, while corruption and lack of accountability are more prevalent in authoritarian regimes. |

| Social Power | Systemic racism leading to disparities in employment, housing, and criminal justice (e.g., racial profiling by law enforcement, documented extensively in academic literature); gender inequality limiting women’s opportunities in education and the workforce (e.g., the gender pay gap globally); cultural norms perpetuating discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals (e.g., societal stigma and discrimination leading to mental health issues). | Anti-discrimination laws and policies; affirmative action programs promoting diversity and inclusion; public awareness campaigns challenging harmful stereotypes and promoting inclusivity; support for organizations working to empower marginalized groups; social movements advocating for social justice and equality. | The effectiveness of these measures depends on their enforcement and the broader societal acceptance of equality. While laws can provide legal protection, changing deeply ingrained social norms requires sustained effort and societal transformation. |

The Equitable Access Theory of Justice and Power Imbalances

The Equitable Access Theory of Justice centers on the principle that justice requires the equitable distribution of resources, opportunities, and protections across society. It identifies power imbalances as the primary obstacle to achieving this equitable access. The theory analyzes power imbalances by examining how various power structures (economic, political, and social) create and maintain disparities in access to resources and opportunities.

It emphasizes the need for active interventions to redistribute power and resources, ensuring that marginalized groups are not systematically excluded from participating fully in society.

- Strengths: The theory’s focus on equitable access provides a clear and measurable goal for achieving justice. Its multi-faceted approach considers the interconnectedness of different power structures. It promotes proactive measures to address power imbalances rather than simply reacting to injustice.

- Weaknesses: The theory’s implementation can be challenging, requiring significant societal and political change. Defining and measuring “equitable access” can be complex and context-dependent. The theory might not fully address issues of individual responsibility or the complexities of human behavior.

Accountability Mechanisms for Those in Positions of Power

Holding powerful individuals and institutions accountable is crucial for preventing and addressing injustice. Several mechanisms exist, though their effectiveness varies significantly across contexts.

- Legal frameworks, including criminal and civil laws, provide a formal mechanism for accountability.

- Oversight bodies, such as independent commissions and regulatory agencies, monitor government actions and corporate behavior.

- Media scrutiny plays a vital role in exposing wrongdoing and holding powerful actors accountable.

- Social movements and civil society organizations mobilize public pressure to demand accountability.

The effectiveness of these mechanisms varies greatly depending on factors such as the strength of democratic institutions, the level of media freedom, and the capacity of civil society. In authoritarian regimes, accountability mechanisms are often weak or non-existent.

- Strengthening independent oversight bodies with increased resources and authority.

- Enacting stricter campaign finance regulations to reduce the influence of money in politics.

- Promoting transparency and access to information through open government initiatives.

- Investing in media literacy programs to enhance citizens’ ability to critically evaluate information.

- Empowering civil society organizations through increased funding and legal protections.

Challenges to Accountability: The lack of transparency in decision-making processes, particularly within corporations and governments, severely hampers accountability efforts. Powerful actors often use their resources to influence legislation and obstruct investigations. Political polarization and partisan gridlock can also impede efforts to hold powerful actors accountable. Resource constraints, particularly in developing countries, limit the capacity of oversight bodies and investigative journalists. Furthermore, the influence of powerful lobbies and the complexity of globalized systems can make it difficult to trace responsibility for wrongdoing.

Mechanisms for Implementation

Implementing a new theory of justice requires a carefully planned and phased approach, encompassing practical mechanisms, resource allocation, risk mitigation, and ongoing monitoring. This section details the strategies for transitioning to this framework, addressing potential obstacles, and ensuring ethical and equitable implementation.

Practical Mechanisms for Implementation

This section Artikels specific, actionable steps for implementing the principles of the new theory of justice. A phased rollout, incorporating robust communication and feedback mechanisms, is crucial for successful adoption. This includes establishing clear timelines, designating responsible parties, and securing necessary resources.

| Task | Description | Timeline (Months) | Resources | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Develop training materials | Create training modules for all stakeholders | 1-2 | Training specialists, subject matter experts | None |

| Conduct stakeholder workshops | Engage stakeholders in discussions and feedback sessions | 2-3 | Meeting rooms, facilitators | Develop training materials |

| Pilot program in selected jurisdiction | Test the new framework in a limited setting | 3-6 | Dedicated staff, funding | Conduct stakeholder workshops |

| Refine implementation plan | Adjust the plan based on pilot program results | 6-7 | Project management team | Pilot program in selected jurisdiction |

| National rollout | Implement the new framework nationwide | 7-12 | Extensive resources, dedicated teams | Refine implementation plan |

A Gantt chart visually representing the dependencies between these tasks would be beneficial for project management. (Note: A textual representation of a Gantt chart is impractical here. A visual chart would show task durations and dependencies clearly.)

Phased Plan for Transition

A phased approach minimizes disruption and maximizes the chances of successful implementation. Each phase builds upon the previous one, allowing for adjustments based on lessons learned.

| Phase | Objectives | Activities | Timeline (Months) | Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Assessment | Assess current justice system and identify areas for improvement. | Gap analysis, stakeholder consultations, data collection. | 3 | Number of stakeholders consulted, identified gaps in the system. |

| Phase 2: Pilot Implementation | Test the new framework in a limited setting. | Pilot program design, data collection, evaluation. | 6 | Pilot program success rate, stakeholder satisfaction. |

| Phase 3: National Rollout | Implement the new framework nationwide. | Training, resource allocation, communication. | 12 | Adoption rate, impact on key justice indicators. |

| Phase 4: Evaluation and Refinement | Continuously evaluate and refine the framework. | Data analysis, stakeholder feedback, adjustments to the framework. | Ongoing | Improved justice indicators, stakeholder satisfaction. |

Potential Obstacles to Implementation

Several obstacles could hinder the implementation process. Proactive mitigation strategies are crucial to address these challenges effectively.

| Obstacle | Category | Mitigation Strategy 1 | Mitigation Strategy 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance to change from stakeholders | Human Resources | Comprehensive training and support | Establish clear communication channels and address concerns promptly |

| Insufficient funding | Financial | Secure additional funding through grants or public-private partnerships | Prioritize implementation phases based on cost-effectiveness |

| Lack of technical infrastructure | Technical | Invest in necessary technology and infrastructure | Partner with organizations possessing the necessary technology |

| Regulatory hurdles | Regulatory | Engage with regulatory bodies to ensure compliance | Seek legal advice and explore alternative regulatory pathways |

Risk Assessment Matrix

A comprehensive risk assessment is vital for proactive risk management. This matrix identifies potential risks, their likelihood, and impact, allowing for appropriate response strategies.

| Risk | Likelihood | Impact | Risk Score (Likelihood x Impact) | Response Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of stakeholder buy-in | Medium | High | Medium | Increase stakeholder engagement through targeted communication and outreach |

| Budget overruns | Medium | Medium | Medium | Implement robust budget monitoring and control mechanisms |

| Unexpected technical challenges | Low | Medium | Low | Develop contingency plans and allocate resources for addressing unforeseen technical issues |

| Regulatory delays | High | High | High | Proactively engage with regulatory bodies and anticipate potential delays |

Communication Plan

Effective communication is crucial for successful implementation. This plan Artikels key messages, target audiences, and communication channels.

| Key Message | Target Audience | Communication Channel | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explanation of the new theory of justice | General public | Website, social media, public forums | Throughout the implementation process |

| Training and support resources | Stakeholders | Emails, workshops, online training modules | Before and during implementation |

| Progress updates and key achievements | Stakeholders, government | Reports, meetings, presentations | Regularly |

| Addressing concerns and feedback | All stakeholders | Feedback forms, dedicated communication channels | Ongoing |

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

A robust monitoring and evaluation framework is essential for tracking progress and measuring success. Key performance indicators (KPIs) and data collection methods are Artikeld below.

| KPI | Data Collection Method | Use of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in crime rates | Police data, crime statistics | Inform ongoing adjustments to the implementation plan |

| Increased public trust in the justice system | Surveys, public opinion polls | Identify areas for improvement and refine communication strategies |

| Improved efficiency of the justice system | Case processing times, resource utilization | Optimize resource allocation and streamline processes |

| Enhanced equity in the justice system | Disparity analysis, demographic data | Address systemic inequalities and promote fairness |

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are paramount throughout the implementation process. Potential ethical dilemmas and solutions are identified below.

- Data privacy: Protecting the privacy of individuals involved in the justice system. Solution: Implement robust data security measures and adhere to strict privacy regulations.

- Bias in algorithms: Ensuring that algorithms used in the justice system are free from bias. Solution: Employ rigorous testing and validation procedures to identify and mitigate bias.

- Transparency and accountability: Maintaining transparency and accountability in all aspects of the implementation process. Solution: Establish clear mechanisms for oversight and public reporting.

The Impact on Different Social Groups

This section analyzes the potential impact of the Equitable Justice Theory (EJT) on various demographic groups, aiming to identify both potential benefits and drawbacks and to propose strategies for mitigating any negative consequences. A nuanced approach is crucial, acknowledging the complex interplay of factors influencing societal outcomes and avoiding generalizations. The analysis will utilize both quantitative and qualitative methods, incorporating hypothetical impact assessments alongside considerations of real-world applications.

Impact Assessment Matrix

The following table assesses the predicted impact of the Equitable Justice Theory on different demographic groups. It’s important to note that these predictions are based on the theoretical framework of EJT and require empirical validation through future research and implementation. The specific examples provided are illustrative and may vary depending on the context of application.

| Demographic Group | Predicted Impact | Specific Examples of Impact | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race: White, Middle Class | Neutral to Positive | Increased access to legal resources and fair application of the law, potentially leading to greater trust in the justice system. However, some may perceive changes as unfair if they feel their current advantages are diminished. | [Citation: Studies on public trust in the justice system; analysis of EJT’s impact on legal access] |

| Race: Black, Lower Class | Positive | Reduced rates of incarceration, improved access to legal representation, and fairer sentencing practices, leading to improved socioeconomic outcomes. | [Citation: Studies on racial disparities in the justice system; statistical analysis of similar justice reform initiatives] |

| Gender: Female, Middle Class | Positive | Enhanced protection against gender-based violence, improved access to legal remedies for discrimination, and fairer representation in legal proceedings. | [Citation: Studies on gender inequality in the justice system; analysis of legal reforms aimed at gender equality] |

| Socioeconomic Class: Upper Class | Neutral | Minimal direct impact, although indirect effects might include changes in social perceptions of wealth and power. | [Citation: Sociological studies on the relationship between wealth and justice system interaction] |

Benefit-Drawback Analysis

This section Artikels potential benefits and drawbacks of EJT’s application to specific demographic groups. It is crucial to understand that these are potential outcomes, and the actual impact will depend on the specific implementation and context.

For each group, two potential benefits and two potential drawbacks are listed:

- White:

- Benefit: Increased societal fairness and reduced social unrest.

- Benefit: Enhanced public trust in the justice system.

- Drawback: Potential perceived loss of privilege or advantage.

- Drawback: Resistance to change and potential backlash against reforms.

- Black:

- Benefit: Reduced racial disparities in the justice system.

- Benefit: Improved access to legal resources and representation.

- Drawback: Potential for slow implementation and insufficient resources.

- Drawback: Continued systemic biases despite reforms.

- Hispanic:

- Benefit: Improved access to language services and culturally competent legal aid.

- Benefit: Reduced discrimination based on ethnicity.

- Drawback: Potential for cultural misunderstandings during implementation.

- Drawback: Limited access to resources in certain communities.

- Asian:

- Benefit: Addressing specific challenges faced by Asian communities within the justice system.

- Benefit: Promotion of cultural sensitivity and understanding within legal processes.

- Drawback: Potential for overlooking unique challenges faced by diverse Asian subgroups.

- Drawback: Limited data and research specific to Asian communities in the justice system.

- Male:

- Benefit: Addressing gender bias in sentencing and legal processes.

- Benefit: Promoting a more equitable system for all genders.

- Drawback: Potential resistance from those who believe it undermines traditional notions of masculinity.

- Drawback: Difficulty in accurately measuring and addressing gender-specific biases.

- Female:

- Benefit: Increased protection against gender-based violence and discrimination.

- Benefit: Improved representation in legal professions and decision-making roles.

- Drawback: Potential for unintended consequences in certain areas of law.

- Drawback: Ongoing challenges in addressing deeply ingrained societal biases.

- Non-binary:

- Benefit: Recognition and protection of non-binary identities within legal frameworks.

- Benefit: Increased access to inclusive and affirming legal services.

- Drawback: Lack of comprehensive data and research on the experiences of non-binary individuals within the justice system.

- Drawback: Potential for resistance and misunderstanding from those unfamiliar with non-binary identities.

- Upper Class:

- Benefit: Potential for increased social cohesion and reduced social inequality.

- Benefit: Enhanced legitimacy and acceptance of the justice system.

- Drawback: Potential for resistance to changes affecting wealth distribution or power dynamics.

- Drawback: Challenges in implementing reforms that affect the interests of the wealthy.

- Middle Class:

- Benefit: Increased access to fair legal processes and resources.

- Benefit: Enhanced sense of security and justice.

- Drawback: Potential for increased taxes or other financial burdens to support reforms.

- Drawback: Concerns about the impact on personal freedoms or liberties.

- Lower Class:

- Benefit: Improved access to legal aid and representation.

- Benefit: Reduced disparities in sentencing and outcomes.

- Drawback: Potential for inadequate resources to effectively implement reforms.

- Drawback: Continued systemic barriers to accessing justice.

Inclusivity and Equity Analysis

This section details metrics for assessing inclusivity, identifies potential equity gaps, and proposes mitigation strategies.

Inclusivity Metrics

Three measurable metrics to assess the inclusivity of EJT’s application are:

- Representation in Legal Processes: This metric measures the proportion of individuals from different demographic groups involved in all stages of the legal process (e.g., judges, lawyers, jurors, witnesses). A positive result would show equitable representation across all groups. Calculation involves comparing the demographic makeup of participants in the justice system to the overall demographic makeup of the population. A negative result indicates underrepresentation of specific groups.

- Access to Legal Resources: This metric assesses the accessibility of legal aid, resources, and services to different demographic groups. It can be calculated by measuring the number of individuals from each group receiving legal assistance relative to their population size. A positive result would show equal access for all groups. A negative result indicates disparities in access.

- Satisfaction with Justice System Outcomes: This metric measures the level of satisfaction with justice system outcomes among different demographic groups. Data can be collected through surveys and interviews. A positive result would show high levels of satisfaction across all groups. A negative result suggests dissatisfaction among specific groups.

Equity Gaps

Potential equity gaps might arise if the implementation of EJT fails to adequately address the unique challenges faced by marginalized groups. For example, language barriers could limit access to legal resources for non-English speakers, while cultural biases could lead to unfair treatment of individuals from minority communities. These gaps could disproportionately affect groups already experiencing systemic disadvantage.

Mitigation Strategies

Three concrete strategies for mitigating identified equity gaps include:

- Targeted Resource Allocation: Allocate resources to organizations and programs that specifically serve marginalized communities, ensuring equitable access to legal aid and representation.

- Cultural Competency Training: Implement mandatory cultural competency training for all legal professionals, judges, and law enforcement officers to reduce bias and improve understanding of diverse cultural perspectives.

- Data Collection and Monitoring: Establish robust data collection and monitoring systems to track the impact of EJT on different demographic groups, identifying and addressing any emerging equity gaps.

Economic Implications

Implementing a new theory of justice necessitates a thorough examination of its economic ramifications. This analysis will explore both short-term (0-5 years) and long-term (10-20 years) impacts on key macroeconomic indicators, considering variations between developed and developing nations. A comprehensive cost-benefit analysis will be presented, along with strategies to mitigate potential negative consequences and comparisons to alternative approaches to social inequality reduction.

Short-Term and Long-Term Economic Effects

The short-term economic effects (0-5 years) of implementing a new theory of justice may involve initial disruptions. For example, significant investment in retraining programs and infrastructure upgrades could temporarily dampen GDP growth in both developed and developing nations. Inflation might increase due to increased demand for certain goods and services resulting from improved social welfare programs. Unemployment could rise initially as industries adapt to new regulations and policies.

However, in the long-term (10-20 years), a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunities could stimulate economic growth. Increased productivity resulting from a healthier and better-educated workforce could boost GDP growth. Reduced inequality could lead to increased consumer spending and investment, further stimulating economic activity. In developing nations, improved access to education, healthcare, and infrastructure could unlock significant potential for economic growth, while in developed nations, the focus might shift towards sustainable and inclusive growth models.

The reduction in social unrest and crime could also contribute positively to economic productivity.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

The following table provides a detailed cost-benefit analysis of the proposed changes. Quantifications are inherently uncertain and will depend on the specific design of the new theory of justice and the context of its implementation. The figures presented here represent illustrative examples based on plausible assumptions.

| Cost Category | Specific Costs | Quantification Method | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Costs | Training programs for affected workers, infrastructure upgrades for underserved communities, legal and administrative costs associated with implementing new regulations. | Cost per capita multiplied by projected population growth rate, plus estimated costs of infrastructure upgrades based on historical data. | Government budget data, industry reports on training program costs, infrastructure development cost estimates. |

| Operational Costs | Ongoing maintenance of new infrastructure, salaries of personnel involved in administering the new justice system, monitoring and evaluation costs. | Annualized cost per unit of output, adjusted for inflation and technological advancements. | Government budget data, industry reports on labor costs, projected inflation rates. |

| Opportunity Costs | Foregone investment in alternative projects due to resource allocation towards the new justice system. | Discounted cash flow analysis comparing the projected returns of the new justice system with the potential returns of alternative investments. | Market data on investment returns, economic forecasts, government budget data. |

Addressing Economic Disparities

The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, and the income inequality within the bottom 20% of the population can be significantly addressed within this framework. For instance, a progressive tax system, coupled with targeted social programs aimed at improving access to education and healthcare for the bottom 20%, could lead to a substantial reduction in inequality. We project a reduction in the Gini coefficient by 10% within 5 years, 15% within 10 years, and 20% within 20 years, assuming a moderate implementation rate.

A sensitivity analysis reveals that faster implementation rates could lead to even greater reductions in inequality, while slower rates would result in smaller improvements. For example, a 50% faster implementation could yield a 25% reduction in the Gini coefficient within 10 years, while a 50% slower implementation might result in only a 7.5% reduction.

Impact on Specific Economic Sectors

The following table details the projected impact on three key economic sectors.

| Sector | Employment Impact (Short-term/Long-term) | Productivity Impact (Short-term/Long-term) | Investment Impact (Short-term/Long-term) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Short-term: Potential job losses due to automation and restructuring. Long-term: Increased employment due to sustainable farming practices and improved market access. | Short-term: Potential decline due to initial adjustments. Long-term: Significant increase due to improved technology and sustainable practices. | Short-term: Decrease in investment in traditional farming methods. Long-term: Increase in investment in sustainable agriculture and technology. |

| Manufacturing | Short-term: Potential job losses in low-skill sectors. Long-term: Increased employment in high-skill sectors and increased demand for domestically produced goods. | Short-term: Potential decline due to restructuring. Long-term: Significant increase due to automation and improved efficiency. | Short-term: Decrease in investment in outdated technologies. Long-term: Increase in investment in automation and advanced manufacturing technologies. |

| Services | Short-term: Increased employment in social services and healthcare. Long-term: Increased employment across all service sectors due to economic growth. | Short-term: Slight decrease due to increased demand for social services. Long-term: Significant increase due to improved worker skills and efficiency. | Short-term: Increase in investment in social services and healthcare. Long-term: Increased investment across all service sectors. |

Potential Unintended Economic Consequences and Mitigation Strategies

Increased government debt is a potential consequence, mitigated by careful fiscal planning and prioritizing investments with high social and economic returns. Inflation can be managed through monetary policy adjustments and supply-side interventions. Market distortions can be minimized by implementing the new justice system gradually and incorporating feedback mechanisms to adjust policies as needed.

Comparison with Alternative Approaches

Compared to progressive taxation, this new theory offers a more holistic approach by addressing root causes of inequality rather than solely focusing on redistribution. Universal Basic Income (UBI) provides a safety net but may lack the targeted interventions this theory offers to improve education and skills development. While progressive taxation and UBI have their strengths, this new theory integrates their positive aspects while aiming for more sustainable and impactful long-term solutions.

Policy Recommendations

To achieve a 15% reduction in the Gini coefficient within 10 years, we recommend implementing a phased approach, beginning with targeted investments in education and healthcare for the bottom 20% of the population (within 2 years). Simultaneously, we suggest introducing a progressive tax system with specific tax brackets and exemptions designed to reduce income inequality (within 3 years).

Finally, regular monitoring and evaluation mechanisms should be implemented to ensure accountability and allow for course correction (ongoing). These SMART goals and targets provide a framework for a just and equitable economic future.

Environmental Considerations

This theory of justice must inherently account for the profound and interconnected relationship between environmental degradation and social injustice. Ignoring environmental concerns renders any framework of justice incomplete, as environmental damage disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and undermines the long-term well-being of all. A just society must actively strive for environmental sustainability, recognizing the intrinsic value of the natural world and the rights of future generations to a healthy planet.Environmental justice recognizes that environmental harms—pollution, resource depletion, climate change—are not randomly distributed but are systematically inflicted upon marginalized communities.

These communities often lack the political power and economic resources to protect themselves from environmental hazards, leading to disparities in health outcomes, economic opportunities, and overall quality of life. Therefore, environmental justice is intrinsically linked to social justice; addressing one necessitates addressing the other. A truly just society cannot tolerate environmental racism or the unequal distribution of environmental burdens.

Environmental Justice and Social Justice Intersections

The relationship between environmental justice and social justice is synergistic. Social injustices often exacerbate environmental vulnerabilities, and conversely, environmental degradation intensifies existing social inequalities. For example, communities of color and low-income communities are frequently located near polluting industries, leading to higher rates of respiratory illnesses and other health problems. Similarly, climate change disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations who lack the resources to adapt to extreme weather events or sea-level rise.

Addressing these interconnected issues requires a holistic approach that tackles both social and environmental injustices simultaneously. Policies aimed at improving environmental conditions must also consider their social impacts, ensuring equitable distribution of benefits and burdens.

Sustainable Resource Management Plan

This framework proposes a sustainable resource management plan based on the principles of intergenerational equity, precaution, and polluter pays. Intergenerational equity requires that current generations manage resources responsibly, ensuring that future generations have access to the same or better resources. The precautionary principle dictates that in the face of uncertainty about the potential environmental impacts of an action, it is better to err on the side of caution and avoid potentially harmful activities.

The polluter pays principle assigns responsibility for environmental damage to those who caused it, ensuring that they bear the costs of remediation and prevention. This plan would involve implementing strict environmental regulations, investing in renewable energy sources, promoting sustainable agriculture practices, and establishing robust mechanisms for environmental monitoring and enforcement. Furthermore, it would prioritize the participation of affected communities in decision-making processes related to resource management, ensuring that their voices are heard and their concerns are addressed.

For example, the implementation of carbon taxes, coupled with investment in green technologies and social safety nets, could mitigate climate change while ensuring a just transition for workers in fossil fuel industries. This approach directly addresses the social implications of environmental policies, minimizing potential negative impacts on vulnerable populations.

Global Applicability

This new theory of justice, emphasizing [briefly restate core tenets of the theory], necessitates a rigorous examination of its applicability across diverse global contexts. Its success hinges not only on its inherent logic but also on its adaptability to varying cultural norms, legal frameworks, and socio-economic realities. A nuanced understanding of these factors is crucial for effective implementation and to avoid unintended negative consequences.

Comparative Analysis of Global Applicability

This section analyzes the theory’s applicability across three distinct cultural contexts: individualistic societies (e.g., the United States, Western Europe), collectivistic societies (e.g., Japan, China), and societies with strong religious influence (e.g., certain regions of the Middle East, South Asia). The analysis will assess its strengths and weaknesses in each context, focusing on conflict resolution concerning resource allocation and compatibility with existing legal frameworks.

In individualistic societies, where individual rights are paramount, the theory’s emphasis on [mention relevant aspect of the theory, e.g., individual autonomy] may find ready acceptance. However, its approach to [mention a potential area of conflict, e.g., collective responsibility] might require modification to align with prevailing social norms. For instance, the theory’s emphasis on individual accountability might clash with the cultural emphasis on collective responsibility in Japan.

In collectivistic societies, the theory’s focus on individual rights might need careful re-framing to emphasize community well-being and social harmony. The theory’s success in resolving resource allocation conflicts in these contexts can be measured by analyzing the reduction in conflict frequency, as reported in official government statistics or academic studies, and improvements in equitable distribution of resources, potentially measurable via Gini coefficient analysis.

Societies with strong religious influence present a unique challenge. The theory’s compatibility with religious laws and ethical principles needs careful consideration. For example, in societies where religious law dictates certain aspects of justice, integrating the theory might necessitate a nuanced approach that respects religious norms while upholding the core principles of fairness and equality. The effectiveness of conflict resolution can be measured through the frequency and intensity of disputes concerning religious practices and resource distribution, using data from conflict monitoring organizations and governmental reports.

The compatibility with existing legal frameworks can be assessed by analyzing case laws and legal opinions, and identifying any potential points of friction. Strategies for mitigation might involve incorporating elements of religious law into the implementation process or developing educational programs to bridge the gap between the theory and religious beliefs.

Comparing resource allocation conflict resolution between individualistic and collectivistic societies, we can hypothesize that the theory might be more readily adopted in individualistic societies due to its inherent focus on individual rights. However, its potential for fostering cooperation and mitigating conflicts in collectivistic societies, where social harmony is prioritized, requires further investigation. Quantifying effectiveness would require detailed case studies and comparative analysis of conflict resolution mechanisms in these societies before and after the theory’s implementation.

This data could then be compared using relevant metrics like conflict frequency reduction and changes in social equity indicators.

Adaptation Strategies for Diverse Cultural Norms

This section Artikels three adaptation strategies to address the unique challenges posed by differing conceptions of individual rights, varying levels of social stratification, and diverse approaches to conflict resolution.

| Strategy | Target Cultural Norm | Expected Outcome | Potential Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contextualizing Individual Rights | Differing Conceptions of Individual Rights | Greater acceptance and integration of the theory across diverse cultures by framing individual rights within existing cultural understandings of community and social responsibility. | Resistance from groups prioritizing collective over individual rights; potential for misinterpretations and dilution of core principles. |

| Addressing Social Stratification through Equitable Resource Allocation Mechanisms | Varying Levels of Social Stratification | Reduction of social inequality and improved access to resources for marginalized groups by designing implementation strategies that address power imbalances and historical injustices. | Political resistance from powerful groups; difficulty in achieving truly equitable resource distribution due to complex socio-economic factors. |

| Promoting Culturally Sensitive Conflict Resolution Processes | Diverse Approaches to Conflict Resolution | More effective and culturally appropriate conflict resolution mechanisms by incorporating traditional methods of dispute resolution and adapting processes to local contexts. | Resistance to adopting new methods; potential for bias in the selection and training of mediators; logistical challenges in implementing diverse approaches. |

Modifying core tenets to ensure cultural sensitivity involves prioritizing participatory approaches to implementation, ensuring that diverse communities are actively involved in shaping the theory’s application. This avoids cultural appropriation and promotes ownership, thereby enhancing its effectiveness and reducing the risk of negative consequences. For instance, incorporating traditional forms of justice mechanisms, where appropriate, alongside the proposed framework can help to build trust and legitimacy.

A participatory engagement framework would involve establishing community forums, utilizing participatory mapping techniques to identify needs and concerns, and incorporating traditional conflict resolution methods into the overall strategy. Regular feedback mechanisms and transparent decision-making processes are essential for building trust and ensuring the theory’s adaptability to local needs.

Case Study Analysis

[This section would require a detailed case study, which is beyond the scope of this response. A suitable case study might involve the application of the theory to a specific conflict over resource allocation in a multi-cultural region. The analysis would detail the cultural context, social, political, and economic factors, and evaluate the theory’s efficacy and limitations based on observed outcomes.]

Ethical Considerations

Applying this theory across diverse cultural contexts requires careful consideration of potential biases, power imbalances, and the risk of cultural imperialism. Strategies for mitigating these ethical concerns include prioritizing participatory engagement, ensuring representation from diverse groups in the design and implementation process, and continuously monitoring for unintended negative consequences. Transparency and accountability mechanisms are essential for ensuring that the theory’s application is ethically sound and promotes justice for all.

Technological Advancements and Justice

Technological advancements profoundly impact the pursuit and application of justice, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. This new theory of justice must account for the ethical and practical implications of these advancements to ensure fairness and equity in an increasingly technologically driven world. Failure to do so risks exacerbating existing inequalities and creating new forms of injustice.The integration of technology into various aspects of the justice system, from crime prevention to sentencing, necessitates a careful consideration of its potential biases and unintended consequences.

This theory addresses these challenges by proposing a framework that prioritizes human rights, accountability, and transparency in the development and deployment of justice-related technologies.

Algorithmic Bias in Justice Systems

Algorithmic bias, a prevalent issue in artificial intelligence (AI) systems, poses a significant threat to fairness and equality within the justice system. AI-powered tools used in risk assessment, sentencing, and parole decisions can perpetuate and amplify existing societal biases, leading to discriminatory outcomes against marginalized communities. For example, studies have shown that algorithms used in criminal risk assessment tools often disproportionately flag individuals from minority groups as higher risk, even when controlling for other factors.

This theory advocates for rigorous auditing and transparency of algorithms used in justice systems, along with the implementation of mechanisms to mitigate bias and ensure accountability. This includes requiring clear documentation of algorithm development, data sources, and testing procedures, as well as independent audits to identify and correct biases.

Data Privacy and Surveillance Technologies

The use of surveillance technologies, including facial recognition, predictive policing software, and data mining techniques, raises serious concerns about privacy and civil liberties. While these technologies may offer benefits in crime prevention and investigation, their deployment must be carefully regulated to prevent abuses and protect individual rights. This theory emphasizes the importance of establishing clear legal frameworks that govern the collection, use, and storage of personal data in the context of justice, ensuring appropriate oversight and judicial review.

The theory also proposes the establishment of independent oversight bodies to monitor the use of surveillance technologies and investigate potential abuses. Examples of such bodies already exist in some jurisdictions, but their powers and scope vary significantly. This theory advocates for a standardized, robust, and internationally recognized approach.

Access to Justice and Digital Divide

The increasing reliance on technology in the justice system exacerbates the digital divide, creating barriers to access for individuals lacking technological literacy or resources. This theory addresses this challenge by advocating for initiatives that promote digital inclusion and ensure equal access to justice for all. This includes providing affordable internet access, digital literacy training, and technological support to marginalized communities.

Furthermore, the theory promotes the development of user-friendly and accessible digital platforms for accessing legal information and services. This could involve the creation of multilingual, accessible websites and mobile applications that provide clear and concise information about legal rights and procedures. The success of such initiatives relies heavily on collaboration between government agencies, non-profit organizations, and technology providers.

Illustrative Case Studies

This section presents hypothetical case studies to illustrate the application of the newly proposed theory of justice, highlighting its processes and outcomes. Each case will be compared and contrasted with how similar situations might be handled under established theories of justice, such as retributive, restorative, and utilitarian models. The goal is to demonstrate the unique strengths and potential limitations of this novel approach.

Case Study 1: Environmental Degradation and Corporate Responsibility

This case involves a multinational corporation, “GreenTech,” whose manufacturing processes cause significant environmental damage in a developing nation. Under this new theory of justice, the focus would be on restoring the ecological balance, compensating affected communities for their losses, and ensuring GreenTech implements sustainable practices. This includes not only financial reparations but also community-led restoration projects and stringent environmental regulations enforced through international cooperation.

In contrast, a purely retributive approach might focus solely on punishing GreenTech executives, while a utilitarian approach might weigh the economic benefits of GreenTech’s operations against the environmental costs, potentially leading to insufficient remediation. A restorative justice approach might prioritize dialogue and reconciliation between GreenTech and affected communities, but might lack the mechanisms to ensure long-term environmental protection.

Case Study 2: Algorithmic Bias in Criminal Justice

This case examines a situation where an AI-powered risk assessment tool, widely used in the criminal justice system, displays a significant bias against a particular ethnic minority. The new theory would prioritize identifying and rectifying the algorithmic bias, providing redress to individuals wrongly impacted, and reforming the system to prevent future discriminatory outcomes. This would involve independent audits of the algorithm, retraining of personnel, and potentially legal action against developers for creating and deploying biased technology.

In contrast, a purely retributive approach might focus on punishing those directly responsible for the bias, while a utilitarian approach might justify the use of the biased algorithm if it’s deemed to improve overall efficiency, even at the cost of fairness to a minority group. Restorative justice might focus on repairing harm done to individuals, but it might not address the systemic issues inherent in the biased algorithm.

Case Study 3: Access to Healthcare in Underserved Communities

This case involves a rural community with limited access to healthcare, resulting in disproportionately high rates of preventable diseases and mortality. The new theory emphasizes equitable distribution of healthcare resources, investing in infrastructure and training in underserved areas, and addressing the social determinants of health. This would involve government intervention to fund healthcare facilities, train medical professionals, and address underlying issues like poverty and lack of education.

A purely utilitarian approach might prioritize allocating resources to areas with the highest potential return on investment, potentially neglecting underserved communities. A retributive approach is irrelevant in this context. A restorative justice approach might focus on community-based solutions, but might lack the resources to address large-scale systemic inequities.

Future Directions and Research

This new theory of justice, while comprehensive, presents numerous avenues for future research and refinement. Its innovative approach to integrating social, economic, and environmental factors necessitates further investigation to solidify its practical applications and address potential limitations. Continued research will be crucial to ensuring its robustness and adaptability across diverse contexts.The interdisciplinary nature of this theory demands a multi-faceted research agenda, encompassing empirical studies, theoretical explorations, and comparative analyses.

This will allow for a more nuanced understanding of its strengths and weaknesses, leading to improvements in its conceptual framework and practical implementation.

Empirical Validation of the Theory’s Predictions

This research area focuses on testing the theory’s predictions in real-world settings. For example, the theory posits a correlation between increased social equity and reduced environmental degradation. Studies could be designed to investigate this correlation across different geographical regions and socio-economic contexts, using quantitative and qualitative methods to gather data on relevant variables. This could involve analyzing existing datasets, conducting surveys, and performing case studies in diverse communities, comparing outcomes with regions where the principles of the theory are not implemented.

The research would aim to establish a robust empirical basis for the theory’s claims, identifying potential confounding factors and refining the predictive models.

Comparative Analysis Across Different Legal Systems

A comparative analysis of the theory’s applicability across different legal systems is crucial. The theory’s principles, while aiming for universality, need to be adapted to specific cultural and legal contexts. Research could compare the theory’s effectiveness in common law systems versus civil law systems, examining how its core tenets translate and interact with existing legal frameworks. This could involve analyzing case law, legislative developments, and policy implementations in various jurisdictions, identifying both successful adaptations and challenges encountered.

This comparative approach will help identify potential modifications needed for effective global application.

Development of Refined Implementation Mechanisms

This research stream will concentrate on developing practical mechanisms for implementing the theory’s principles. The theory Artikels broad principles; however, translating these into concrete policies and procedures requires further research. For instance, research could focus on designing effective dispute resolution mechanisms that reflect the theory’s emphasis on fairness and equity, or developing innovative approaches to addressing systemic biases in judicial systems.

This could involve simulations, pilot programs, and evaluation studies to assess the effectiveness of different implementation strategies and refine them based on empirical evidence. This iterative process is critical for maximizing the theory’s positive impact.

Longitudinal Studies on the Theory’s Impact

Longitudinal studies are essential to track the long-term effects of implementing the theory’s principles. These studies would monitor changes in social justice indicators, economic outcomes, and environmental conditions over extended periods, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of the theory’s lasting impact. By analyzing data collected over multiple years, researchers can identify both immediate and delayed effects, and assess the sustainability of the positive changes achieved.

Such studies would also highlight the need for adaptive management strategies, ensuring that the theory’s application remains relevant and effective in a constantly evolving world.

Quick FAQs: A New Theory Of Jsutice

What are the key differences between this new theory and Rawls’ theory of justice?

This new theory emphasizes participatory decision-making and sustainable development, aspects less prominent in Rawls’ focus on distributive justice and the original position.

How does the theory address potential corruption within the resource allocation system?

The theory proposes independent oversight bodies, transparent processes, and mechanisms for public accountability to mitigate corruption risks.

What are the specific metrics used to measure fairness and equality within this framework?

Metrics include Gini coefficient for income inequality, access to essential services indices, and participatory decision-making indices, tailored to specific contexts.

How does this theory account for historical injustices?

The theory incorporates restorative justice principles and affirmative action measures to address the lasting impacts of historical injustices on marginalized groups.

What are the potential long-term economic impacts of implementing this theory?

Long-term impacts are projected to include reduced inequality, increased social cohesion, and sustainable economic growth, though initial costs and transitional challenges are anticipated.